Strange Fruit: The forgotten British psychedelic bands whose records might help pay off your mortgage

Britain's Swinging 60s gave birth to a deluge of bands lost to the mists of time – but today their releases are worth a small fortune

Even though its heyday was compressed to little more than a matter of months, British psychedelia certainly left an indelible footprint on the landscape of rock and pop.

From The Beatles’ genre-defining sonic experiments, loosely stretching from Tomorrow Never Knows through to Magical Mystery Tour, the emergence of the original, Syd Barrett-era line-up of Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix launching his meteor-like career from London, Traffic setting a rock archetype (and soon enough, a cliché) by “getting it together in the country” and Procol Harum, The Moody Blues and The Nice laying the foundations for classic/art rock by fusing quasiintellectual lyrics with classical-inspired melodies – all these and more besides have been established parts of rock iconography for a long time.

But what eventually became the public face of Britpsych only scratches the surface. Nobody would deny the potency or status of the era’s acknowledged high watermarks, but genre aficionados pay far more attention to the soft white underbelly of the movement. While not too many people may have noticed at the time, this underground movement was responsible for producing some magnificent music.

Original copies of albums by such obscure bands as July, Forever Amber, Second Hand and Arzachel now sell for staggering sums of money as interest in the lost gems of the era continues to grow and demand hopelessly outstrips supply.

The existence of such posthumously-proclaimed cult classics owes much to the determination of the era’s record companies to prove that they had their finger on the pulse (which, given the original sales figures of such albums, they clearly didn’t).

As with the beat boom explosion a few years earlier and the punk feeding frenzy a decade later, the major record labels were nonplussed by the arrival of an alien and disturbing new sound, and they covered their confusion by signing up anything and everything that might conceivably prove to be popular with the Great Unwashed.

EMI, for example, had initially turned down the chance to sign the nascent Pink Floyd when tipped off in the spring of 1966 by Donovan’s manager Peter Eden, who’d stumbled across the band when they appeared on the same bill as Donovan at the Marquee’s now-legendary Spontaneous Underground happenings.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Having been forced to fork out a rather sizeable advance to secure the Floyd’s signatures a few months later, EMI weren’t about to make the same mistake twice. They duly snapped up Eden’s latest protégés, Southend band The Fingers. In October 1966, the band were named and shamed as part of The Sun’s risible shock-horror exposé of the new music, (headed ‘Psychedelic, the new and dangerous word in pop music: a warning’) identifying them as one of the earliest British groups to be dabbling in the evils of psychedelia.

Despite (or maybe because of) The Sun’s dire warnings, the floodgates of psychedelia were about to open. EMI also signed pre-Groundhogs outfit Herbal Mixture, a popular club act who made a couple of great grunge-psych singles, as well as indulging arch-looner Zoot Money during his Summer of Love musical volte-face with psychedelic warriors Dantalian’s Chariot, whose The Madman Running Through The Fields remains one of the strangest and most fondly-remembered non-hit 45s of the era.

The label also took a chance on Tomorrow, featuring vocalist Keith West and future Yes guitarist Steve Howe, as well as Tales of Justine, a wide-eyed flower-power teen trio from the killing fields of Potters Bar. The latter were handled by Antim Management, a short-lived venture from an EMI junior by the name of Tim Rice with his partner Andy Webber (as the future Lord Lloyd Webber styled himself at the time).

Not to be outdone, Decca rounded up a posse of psychedelic pop hopefuls and herded them onto their new ‘experimental pop’ subsidiary, Deram. The likes of Procol Harum, The Move and The Moody Blues ensured that Deram was an instant success, but in retrospect, the label was arguably more interesting for its succession of maverick one-offs than its billboard stars – particularly Tintern Abbey, a hippie quartet who’d formed after the chance meeting in a Chelsea dole queue of singer David MacTavish and bassist Stuart Mackay.

Managed by teenage millionaire Nigel Samuel (who financed the British counterculture’s parish magazine, IT), sadly Tintern Abbey only issued the one single, Beeside b/w Vacuum Cleaner, but it has become widely regarded as one of the pinnacle achievements of British psychedelia, and original copies now sell for upwards of £700 on the rare occasions that they surface

Fetching a similar figure these days is another double-sided UK psychedelic nugget, the phased-to-the-max Fredereek Hernando b/w Double Sight. The song was by Scottish exiles One In A Million, who included 14-year-old guitarist Jimmy McCulloch in their ranks.

McCulloch’s elder brother Jack was the band’s drummer, but he also moonlighted on a couple of albums that were released by Saga, a budget label determined to get down with the kids just as long as it didn’t cost them too much money. This Is The Magic Mixture featured the songs, guitar and vocals of future Charlie frontman Jim ‘Terry’ Thomas, but marginally the better of the two was a concept album entitled Five Day Week Straw People – a vehicle for the songs of two Clapham-based hairdressers, David Montague and Guy Mascolo (co-founder of international poncey hair salon Toni & Guy), who made the album for a miserly advance of £75.

With deals like that around, perhaps it wasn’t surprising that, in a forerunner of the punk-era indie/ DIY label mentality, some groups decided to finance and release their own recordings.

Featuring future WOMAD stalwart Steve Coe, Blackpool group Complex cut a couple of albums that were sold to local fans, while Cambridge covers band Forever Amber (including keyboardist Chris Parren, who subsequently a highly successful career as a session man and who played on George Michael’s Careless Whisper) hooked up with songwriting student John Hudson to make a Zombies/Left Banke-style baroque pop album, The Love Cycle, which they pressed in a total quantity of 99 copies (pressing 100 or more would have left them liable to pay Purchase Tax). The album’s retail price was fixed at one pound, but let’s hope group members held onto one or two copies: original pressings now sell for around £2,500!

Down on the South Coast, Brighton group the Mike Stuart Span had been dropped by EMI after a couple of flop singles. Undaunted, they cast off their previous soul/R&B shackles, reinvented themselves as fearless psychedelic adventurers and pressed up their own single, the magnificent Children Of Tomorrow.

The band would subsequently sign to Elektra (at which point they were forced to change their name to the heavier-sounding Leviathan), but sadly their 15-minute sci-fi song cycle, rather prosaically entitled Cycle, was restricted to an airing at the Brighton Arts Festival.

The band were also regulars at the Brighton College of Technology, where a pharmacy student by the name of Harvey Goldsmith was the social secretary… But the college/university circuit wouldn’t really become established until the end of the decade.

Although there were regional outposts of good taste during 1967/68 – Mothers in Birmingham was always a hip venue – the younger, aspirational bands of the psych era had little choice but to move to the traditional epicentre of the British music industry, London.

It worked out for Leicester band the Family (they quickly dropped the definite article), but Welsh psychsters Jade Hexagram and Dorset bunch The Crystal Ship – named after a Bob Dylan phrase and a Doors song respectively – suffered a more typical fate. Both managed to land prestigious gigs at leading underground venue Middle Earth, but still never got as far as releasing a record.

Even so, they got closer than Hull band The Rats, who, tired of being big fish in a small pool, decided to move down to London. Living in the back of their van, the group’s valiant attempt to locate streets that were paved with gold ended when they threw in the towel after only a week, having failed to find a single paid gig in that time. At least there was a happy ending for Rats guitarist Mick Ronson, who, after a spell as a municipal gardener in Hull, returned to London like a latter-day Dick Whittington to play second banana to David Bowie.

Middle Earth and UFO (who helped establish the likes of the Floyd, The Soft Machine, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown and Fairport Convention, at that time a heavily West Coast-inspired act) were arguably the key London psychedelic dungeons, but there were plenty of other venues vying for a piece of the action.

Though not widely associated with psychedelia, the long-established Marquee Club always went with the flow, which meant that, for a brief time, they regularly showcased the runners’ n’ riders in the lysergic pop stakes.

February 1968 was a typical month at the Marquee, with established names like Fleetwood Mac, The Nice and Marmalade rubbing shoulders with a plethora of wannabes (Robert Plant & the Band of Joy, pre-Badfinger group the Iveys, the Open Mind, Irish band Granny’s Intentions, Liverpool hoodlums the Klubs, pre-Uriah Heep act the Gods) and a handful of groups who, with the best will in the world, never even became household names in their own households (Sunshine Garden? The New Nadir?!).

It was a similar story at London’s other clubs and watering holes. The short-lived Happening 44, pre-Middle Earth venue the Electric Garden, the Cromwellian, Hatchetts Playground, Tiles and the Scotch of St. James all played host to a motley selection of psychedelic acts, many of whom weren’t so much second division as Beazer Homes League.

Naturally enough, a number of bands (or, more accurately, their booking agencies) managed to get relatively high-profile gigs to coincide with their latest releases, with the little-known July even promoting their self-titled album by sharing a Middle Earth bill with Pink Floyd.

However, some of the era’s more obscure albums didn’t even benefit from the modest publicity engendered by a live show. Five Day Week Straw People and Motherlight (the latter recorded by Bobak Jons Malone, who, despite sounding like a group of solicitors, were actually a trio of Morgan Studios engineers/arrangers) were purely studio projects, as was an album on the Evolution label that was credited to Arzachel – actually Steve Hillage and the members of Egg, who were already under contract to Decca and thus obliged to remain anonymous.

Sadly, Bill Wyman protégés The End were in no position to publicise their masterwork, Introspection, which was delayed for so long that the band splintered before it came out. Possibly the most bizarre reason for the non-promotion of a bona fide UK psych cult classic, though, came with Art’s album Supernatural Fairy Tales. The group’s record label, Island, issued the set in December 1967 – some two months after Art had enlisted a fifth member, organist Gary Wright, changed their name to Spooky Tooth and decided to move on from their previous work. In retrospect, it seems strange to think that, without a band to promote it, Island even bothered to release the Art album… still, we’re glad they did.

But nothing lasts forever, particularly in the fast-moving world of 1960s British pop, and by the turn of the decade, psychedelia had evolved into progressive rock – a far more sombre beast than its largely frivolous, technicolored predecessor.

One or two bands certainly benefitted from the shift in musical emphasis: Yes, for example, were a kind of supergroup in reverse, their members having served fairly obscure apprenticeships with a number of unsuccessful psych bands (the Syn, Mabel Greer’s Toyshop, Yellow Passion Loaf).

Generally speaking, though, the bulk of righteously obscure psychedelic bands simply became righteously obscure progressive rock bands: Blossom Toes changed their name to B.B. Blunder, Kaleidoscope became Fairfield Parlour, The End mutated into Tucky Buzzard, while July supplied the backbone of Jade Warrior.

So it goes. But as both Hippocrates and the Nice have seen fit to observe, ars longa, vita brevis – life is short, art is long. Decades years after they were planted, the rarest, most impossibly exotic blooms to have flowered in the secret garden of British psychedelia have belatedly emerged out of the shade and into the sunlight.

It’s about time.

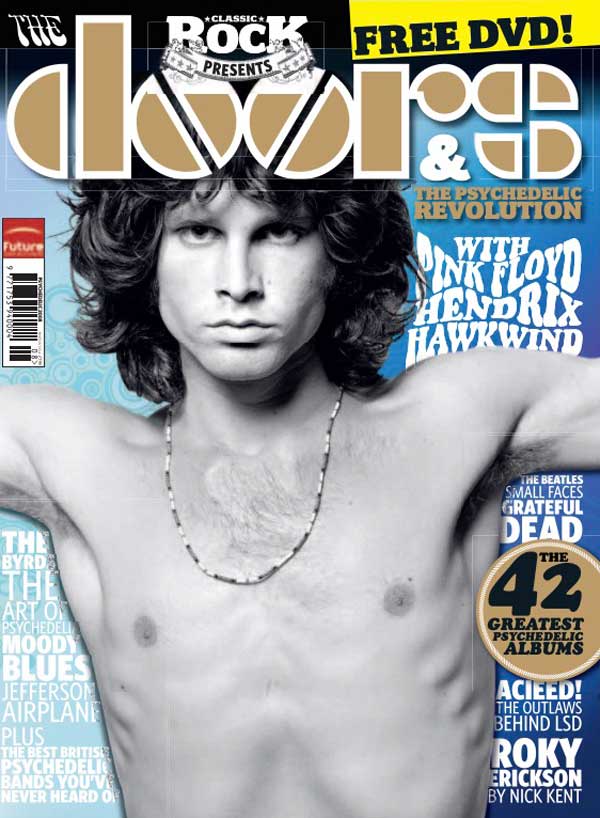

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock Presents The Doors & The Psychedelic Revolution, published in 2008.

David Wells is a music journalist and historian. He is the compiler Real Life Permanent Dreams: A Cornucopia Of British Psychedelia 1965-1970 and dozens of other compilations, the author of liner notes of albums by Jeff Beck, Marmalade, The Nice, Colosseum and many more, and the manager of Grapefruit, Cherry Red’s bespoke psych/garage-era imprint.