10 albums on the legendary Harvest label you should definitely own

Starting out as a haven for the bands EMI didn’t know what to do with, Harvest Records soon proved that there was life beyond prog. These are the label's best albums

Launched by EMI in mid-1969, Harvest Records was a microcosm of the huge musical range of the exploding underground scene at the turn of the decade. Realising that the EMI corporate image was unlikely to attract anyone waving their freak flag high, and aware of the counter-cultural attractions of new indie labels like Island, the EMI suits set up Harvest, put fast-rising management trainee Malcolm Jones (who’d impressed the accountants by producing Love Sculpture’s Sabre Dance) in charge and stepped back.

A sizeable chunk of Harvest’s initial roster came from other EMI labels who took the opportunity to dump ‘unsuitable’ acts like Pink Floyd, Deep Purple, the Pretty Things, The Move, Climax Blues Band and Barclay James Harvest. Rather than thinking about what to do with them, Malcolm Jones and his team let them do what they wanted.

This enlightened A&R policy extended to Harvest’s own signings that included grunge politico hippies the Edgar Broughton Band, stoned raga merchants Third Ear Band, Cream lyricist Pete Brown & His Battered Ornaments, the self-explanatory Panama Limited Jug Band, renegade minstrel Michael Chapman and respected folkies Shirley & Dolly Collins.

It has to be said that with two monstrous exceptions Harvest’s commercial track record was pretty slim. Bands like Tea & Symphony, Bakerloo, Greatest Show On Earth, Quatermass and Forest all had their moments, but not enough to raise a serious fan base.

The two exceptions were of course Deep Purple and Pink Floyd, whose success more than paid for all the one-hit (or less) wonders. Harvest should have done better with Barclay James Harvest, the Pretty Things and even ELO, but they didn’t. They did, however, nurture cult heroes like Roy Harper, Kevin Ayers and Syd Barrett. They also spotted Bill Nelson and Be-Bop Deluxe ahead of the rest to give their mid-70s profile a boost.

Punk should have wiped out Harvest, but by sticking to their instincts they landed seminal Aussies The Saints, The Shirts from New York and London’s very own Wire, not to mention the soundtrack to the revolution with The Roxy, London WC2. Post-punk proved more than Harvest could handle, however, and by the mid-80s it was just another EMI label.

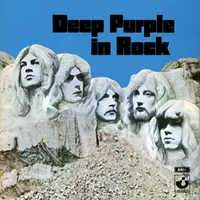

Deep Purple - Deep Purple In Rock (1970)

The Deep Purple line-up that recorded Harvest’s first release, Book Of Taliesyn, was already breaking up in July 1969. And there was another, self-titled, album to come from the Mark 1 band later that year. The first release from the legendary Mark II line-up was the over-ambitious Concerto For Group And Orchestra, but it got them noticed.

Meanwhile, songs from their next album were already getting rave live reviews, and when Deep Purple In Rock came out in June 1970 it was an astonishingly well-honed slab of dramatic hard rock. The album never got higher than No.4 but it stayed in the UK album chart for 16 months while the band toured relentlessly.

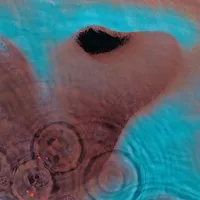

Meddle is the sound of a band groping aimlessly and gradually finding their own style, best illustrated by the way the 23-minute centrepiece Echoes was previously known as Nothings, Son Of Nothings and then Return Of The Son Of Nothings. Harvest’s involvement was limited to the label manager occasionally showing up with “a couple of bottles of wine and a couple of joints”.

Melody Maker thought they were damning the album with faint praise when they called it “a soundtrack to a non-existent movie”. But Floyd fans were perfectly capable of coming up with their own movie to accompany it, particularly if they followed the Harvest diet.

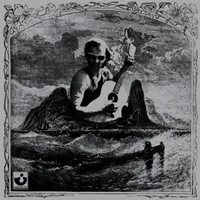

Barclay James Harvest - Harvest Barclay James Harvest (1970)

There’s some debate about how much Barclay James Harvest influenced the name of the label, but as the band’s Woolly Wolstenholme says: “It’s a bit too obvious for it not to be named after us.”

This debut was a scintillating prog concoction with shades of the Moody Blues, Pretty Things and the Bee Gees, all filtered through the songwriting of John Lees and Les Holroyd at their remote farmhouse, the tracks awash with fine harmonies, surging Mellotrons and lush orchestral arrangements. But the band and label never bonded and the album failed to chart.

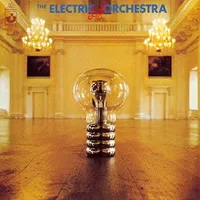

Electric Light Orchestra - Electric Light Orchestra (1971)

Trapped and frustrated by the image and expectations of The Move, Roy Wood and Jeff Lynne plotted a new direction with the Electric Light Orchestra. When they finally got the chance, their contrasting visions of a classical rock fusion gave the band’s debut album a brilliant but fragile friction as each of them strove for supremacy.

Sadly it couldn’t last, and even as Lynne’s 10538 Overture was breaking into the Top 10, Wood was throwing in the towel. No subsequent ELO album rose to the challenge of the first, although most were more commercially successful.

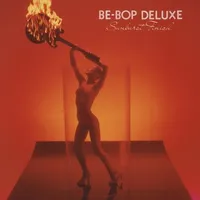

Be-Bop Deluxe - Sunburst Finish (1976)

Always uncomfortable with the idea of making commercially successful pop music, Bill Nelson and Be-Bop Deluxe nevertheless came dangerously close with their third album. All the angular songwriting and sharp playing couldn’t disguise a pop/rock sensibility overlaid with a calculated new-wave attitude.

On the evidence of the slick riffs and sinuous melodies of Fair Exchange and Sleep That Burns, not to mention the fiercely anti-religious Blazing Apostles, Be-Bop Deluxe could fairly lay claim to being Yorkshire’s answer to Talking Heads. They even scored a top 30 hit with the vibrant Ships In The Night.

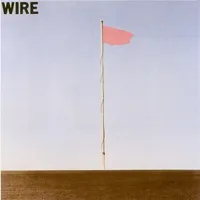

Despite releasing the seminal early punk collection The Roxy, London WC2, Harvest failed to sign any of the participants apart from Wire. Their debut was an amphetamine-crazed art-school dance where many of the 21 tracks, including pogo anthem 12XU, lasted barely a minute. As a statement of intent it was brutal, brief and yet defiantly articulate.

Wire were adored by the critics, who believed they epitomised the spirit of punk, but the general public were not so sure. And neither were the band, to judge from their obstinate refusal to make any commercial concessions from here on in.

Michael Chapman - Fully Qualified Survivor (1970)

An uncompromising folk-based singer-songwriter who remained resolutely rooted in his native Hull, on his second album Michael Chapman sublimated his dextrous guitar style for the sake of the songs.

The exquisite playing and simple but effective production camouflaged a lyrically dark loneliness that permeated much of the album, particularly on songs like Aviator, Kodak Ghosts and Stranger In The Room. It all peaked on the deceptively languid, desperately melancholic songscape of Postcards Of Scarborough. The album remains a timeless gem in the Harvest catalogue.

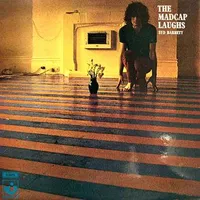

Syd Barrett - The Madcap Laughs (1970)

When Syd Barrett emerged from his post-Pink Floyd exile, Malcolm Jones painstakingly guided him back into the studio and produced the early sessions before his former Floyd bandmates David Gilmour and Roger Waters arrived to complete the process. The Madcap Laughs is the compelling sound of a fractured genius in meltdown.

There are moments of brilliance – the gloriously left-field Octopus, the fragile Late Night, the brooding Dark Globe and the poetic Golden Hair – but the timing is frequently precarious and Barrett’s vocals vary alarmingly in pitch. The production is raw, and the end result, like Barrett, is unfixable.

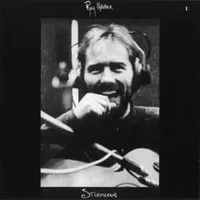

A product of the 60s folk boom, Roy Harper travelled to Big Sur, California, to write his fifth album. The vibes didn’t soften his abrasive attitude, instead they honed it.

Across four lengthy acoustic tracks embellished with string and brass arrangements and some judicious Jimmy Page, Harper delivers a withering attack on organised religion (The Same Old Rock), the glamourisation of war (One Man Rock And Roll Band) and, perceptively, the environment (Me And My Woman). The opening Hors d’Oeuvres only really makes sense when you’ve heard the other three songs. So you’ll play it again and again.

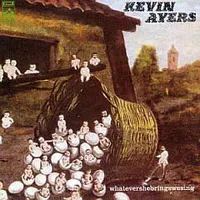

Kevin Ayers - Whatevershebringswesing (1971)

Die-hard Ayers fans tend to dismiss his third album for its consistency, but it’s the best place to get a toehold on the erratic enigma behind the baritone whimsy. The opening mini-suite, with its dramatic orchestral arrangements, is a last look back at the prog style that had characterised Ayers’s career thus far.

Thereafter the songs are less complicated: Stranger In Blue Suede Shoes flirts with vintage rock’n’roll, Champagne Cowboy Blues is a skewed country tease, and the creepy Song From The Bottom Of A Well is a glimpse into the future. After this the whole Ayers catalogue is your oyster.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.