Lazy revisionist theory has tended to reduce psychedelia to a set of cosmetic symbols from the ‘60s underground - beads, bangles, acid tabs, peace signs and the rest of it. In reality, it was an era of complex and deep-rooted change in musical culture, with artists reshaping existing forms and mapping out entirely new ones in a sensory climate of freedom of expression. And while not everything was successful, or even worthwhile, in the right hands rock music could be as mind-altering as the drugs that often went with it. Here are ten shining examples…

Grateful Dead - Anthem Of The Sun (1968)

Described by drummer Mickey Hart as “our springboard into weirdness”, the Dead’s second album is a mutable collage of rock, psychedelia and wayward blues. It’s based on what seems like an unwieldy premise – stitching together various live takes of the same song with new cuts – but somehow works as a vast, cinematic entity. The fact that Jerry Garcia and company were constantly stoned, and given unlimited studio time, only adds to the sprawly majesty of epics like New Potato Caboose and That’s It For The Other One.

The Zombies - Odessey And Oracle (1968)

Such was their disillusionment with the music business that The Zombies split up before their second album was even released. Cut at Abbey Road’s Studio 2 in the immediate wake of Sgt. Pepper…, its title the result of a spelling goof by their sleeve designer, Odessey And Oracle was a psych-pop masterpiece, intricately arranged and woozy with melodic invention. Rod Argent’s command of Mellotron (supposedly left behind by John Lennon) enabled him to conjure rich orchestral textures, an effect heightened by piano and harpsichord.

Aphrodite’s Child - 666 (1972)

European psychedelia never went further out than this weighty concept album about The Book Of Revelation, delivered by a mercurial band that included Vangelis and a pre-superstar Demis Roussos. Utterly at odds with the vaporous sunshine pop of Aphrodite’s Child’s earlier stuff, 666 brought great dollops of proggy weirdness, wildly experimental forms, eerie vocal chants and, via the imperious The Four Horsemen, heavy intimations of the apocalypse. All The Seats Were Occupied is a mammoth 20-minute jam, while actress Irene Papas simulates an orgasm on the genuinely startling Infinity.

The Flaming Lips - The Soft Bulletin (1999)

Firmly placing the Oklahoma City trio at the forefront of postmodern psychedelia, The Soft Bulletin joined the dots between the day-glo ‘60s and the knowing ‘90s with some aplomb. Symphonic detail abounds – synthesizers, strings, choirs, spacey pedal steel, billowy freak-pop – as the Lips create a vivid soundtrack to a futuristic Summer of Love in which there’s hope for humanity after all. It also heralded the arrival of the band as a skewed commercial entity after years of cultdom.

The United States Of America - The United States Of America (1968)

Ring modulators, musique concrète and arty electronica may not have been standard hallmarks of psychedelia, but The United States Of America were every bit as persuasive as West Coast peers like Love or the Dead. Driven by Joseph Byrd, a former pupil of John Cage, and cool-toned singer Dorothy Moskowitz, the band’s sole album is a connoisseur’s classic, fearlessly inventive and often strangely accessible. Pick of the bunch is The American Way Of Love, a three-part suite that deconstructs California’s entire hippie mythos.

Hawkwind - Hall Of The Mountain Grill (1974)

The absence of lyricist Robert Calvert and electronics wizard Dik Mik didn’t prevent Hawkwind from uncorking arguably their finest studio album. The follow-up to 1973’s live Space Ritual, Hall Of The Mountain Grill doesn’t hang out, its space-rock manifesto made clear from the off with the cosmic skronk of The Psychedelic Warlords (Disappear In Smoke). D-Rider, You Better Believe It and Lost Johnny (co-written by Lemmy and Mick Farren) keep the riff count moving, while phased synths and more becalmed passages add a reassuringly trippy backdraft.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Axis: Bold As Love (1967)

Released just seven months after their scintillating debut, the JHE’s second album cemented Hendrix’s reputation as a guitar virtuoso, but also illustrated his growth as a songwriter, offering visionary pieces that ingested the spirit of the psychedelic era. Axis… is freer and more experimental, the band making full use of the studio by harnessing backwards effects, phasing and glorious stereo pans. Bold As Love, Spanish Castle Magic and Little Wing are exemplary, though the standout is the trippy acid-blues of If 6 Was 9.

The 13th Floor Elevators - The Psychedelic Sounds Of…, (1966)

The splenetic proto-punk of lead-off single You’re Gonna Miss Me proved to be something of a false trailer for its parent album, an intense trip designed to approximate the LSD experience. Lead singer Roky Erickson would soon become a tragic figure in the Elevators’ story, incarcerated on a drug charge and subjected to electro-shock treatment that resulted in years of mental illness. But his raw howl was one of the defining features of the Texans’ mighty debut, alongside Stacy Sutherland’s fierce guitar and the disorientating wobble of Tommy Hall’s amplified jug.

Love were in some disarray by the summer of ’67, hobbled by internal squabbles, lack of commercial success and drug addiction. Then there was the mercurial logic of leader Arthur Lee, who preferred Bela Lugosi’s old mansion in the Hollywood hills to the prospect of playing live. Lee pored his conflicted relationship with West Coast flower-power into Forever Changes, a baroque masterwork that managed to be as warm and rapturous as it was acidic and demented, full of brassy flourishes and semi-symphonic folk.

Pink Floyd - The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn (1967)

Before he became lost altogether, Syd Barrett was a source of child-like wonder at the head of Pink Floyd, his imagination disappearing down rabbit holes and coming back up with guileless songs about bikes, gnomes, scarecrows and mice called Gerald. The result was a very British distillation of the psychedelic encounter, the Lear-like playfulness of many of his lyrics finding a contrast in eruptive cosmic-blues jams like Astronomy Domine and freeform epic, Interstellar Overdrive. Nearly half a century on, Floyd’s debut still sounds like nothing else.

Spirit - Twelve Dreams Of Dr. Sardonicus (1970)

Often regarded as Spirit’s finest album, it’s here that Randy California gives full vent to his inner fears of life’s drift. Encouraged by producer David Briggs, his guitar performances are both virtuoso yet also emotionally entangled. It’s as if he’s struggling to come terms with the unpredictabilities he faces every day. And this leads to some of his most electrifying playing.

Of course, this is isn’t just about California, with the rest of the band, especially Jay Ferguson who complements California on keyboards and percussion.

There are moments when the magic is temporarily dissipated, but that never maters. It’s the overall character and feel of this album that matters. The oft-repeated mantra ‘Life has just begun’ is perhaps the fulcrum of the album’s attitude. But this is used to highlight the fragility of existence. And more than 40 years later, its message still chimes loudly – life is for living, whatever the consequences.

The Golden Dawn - Power Plant (1968)

The Texans were both championed and shafted by the 13th Floor Elevators. It was the latter who recommended The Golden Dawn to their label, International Artists. But while the band recorded Power Plant, their debut album, in 1967, its release was inexplicably delayed a year, because the label wanted to put out Easter Everywhere, the second Elevators album, first.

And when this remarkable album was finally put out, it was given such a critical mauling that the discouraged band split up. Many reviews unfavourably compared this to the Elevators, when the truth was that The Golden Dawn were the better band. This album is inventive and inspired, with some crucial guitar timbres from George Kinney, Tom Ramsey and Jimmy Bird.

While not strictly a concept album, there is a theme running throughout. It’s about the dawn of enlightenment, and how that could be corrupted if we’re not careful. In recent years, this has become something of a cult album. But if the label had done the right thing in 1967, who knows what The Golden Dawn would have achieved.

The one-time Moby Grape man is often compared to Syd Barrett, with good reason. Like the Pink Floyd genius, Spence was plagued by bouts of lucid brilliance and incoherent cries of torment. But unlike Barrett he had one solo album that is utterly compelling.

The songs on Oar were written by Spence during a six-month stay in a New York hospital after attacking two Grape bandmates with an axe. Legend has it that when he was released, Spence got on a motorbike and rode down to Nashville, while still in his hospital gown! He teamed up with producer David Rubinson, and recorded this collection of songs that gave an incredible insight into his mauled mind. At times, the album so exposes Spence’s vulnerable psyche that it is almost voyeuristic listening. At other turns, it is downright harrowing. But this holds the attention with a mesmeric maze of insights.

Rubinson kept the production sparse, and allowed Spence to relate his tales of darkness and salvation. Nobody has better captured the insolence and insouciance of insanity brought on by drugs. This is a musician who fully bared his soul and probably didn’t actually feel any cathartic reward for his bravery and bravura.

The album was released by Columbia in with no marketing back-up, and became the lowest selling record in the label’s history up until that point. But it was never forgotten, and in 1999 the likes of Robert Plant, Tom Waits and Mark Lanegan paid homage to Spence by recording More Oar: A Tribute To The Skip Spence Album. It’s said this was played to the man while he lay dying in a hospital bed. According to myth, when the last track faded away, Spence looked up, smiled and then faded away himself. Probably nonsense, but it would have been appropriate if he eventually found some peace through his own masterpiece.

The Moody Blues - In Search Of The Lost Chord (1968)

In 1968, The Moodies immersed themselves totally in the psychedelic waters. After their breakthrough the previous year with Days Of Future Passed, this time they took a real swing into the challenging and timely vibe of the whole pysch process.

There was mysticism here, glowing alongside philosophical mantras built on the twin treatises of drugs and alternative lifestyles. The Moodies embraced the mood and tempo of the Beatles among others, in experimenting with ideas and also bringing in different instruments. If Days Of Future Passed was disciplined and maybe lacking in adventure, the same could not be said here. The band threw out all the rules, in the process proving any reputation for being staid was way off the mark.

The theme of the album was the eternal, restive quest for truth. But there was also an underlying humour, which showed that the Moodies weren’t being seduced by the quick fix of any passing Eastern guru.

Most memorable tracks are Legend Of The Mind, which was inspired by Timothy Leary, House Of Four Doors, The Best Way To Travel and Ride My See-Saw. But everything here works supremely. This includes Justin Hayward’s incorporation of sitar, Graeme Edge using tabla and Mike Pinder bringing the Mellotron into sharp focus.

While the band had more successful albums, they never again truly pushed the envelope as they did here. It was a bold statement that made them one of the UK’s finest psychedelic explorers. In fact, what they showed everyone else was that psychedelia was never about repetition. This was, and should always have been, a one-off album. The perfect psych turn on.

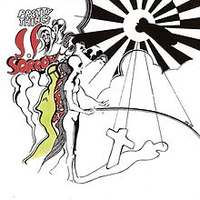

The Pretty Things - S.F. Sorrow (1968)

Who released the first ever rock opera? If you said The Who, then go immediately into remedial rock classes. This album came out in December 1968, nearly six months before Tommy.

The concept is built around Sebastian F. Sorrow, whose life is tracked from birth to old age, and there are some similarities in construction to Tommy, even though The Who have long denied S.F. Sorrow was any sort of influence. But this does not need the more famed Pete Townshend work as a crutch. It stands in its own right.There’s a sense of musical achievement here that makes the overall ambition of this album seem sensible. The pyrotechnic psychedelia is melodramatic and does credit to what was a pioneering format at the time.

Unfortunately, EMI refused to promote the album, believing it was too dark and negative to have mass appeal. It also didn’t help that this was released the same week as the Beatles’ White Album. But a notable lack of profile means S.F. Sorrow hasn’t been overhyped and overplayed down the years, and its freshness is maybe a contrast to the overly exposed Tommy, seminal though the latter unquestionably is.

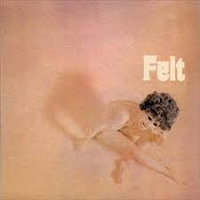

Stan Lee No, not that bloke from Marvel Comics, but the guitarist in The Dickies. Several years before he threw in his lot with those punk types, Lee was a member of Felt, an Alabama psych band whose self-titled, debut album lit up 1971, but failed to sell. Well, they were on the little known Nasco label, which might explain the commercial constipation.

But what these six tracks show is a young band who even in this formative part of their career had a grasp of how to impress through their creativity without toppling over into the torpor of self-indulgence.

The Change is the big song here, and has Beatles-esque pysch moments that bring out the colour and shape of the musical tone. Mixed in there are jazz and blues daubs, to add to the flavouring.

The flow is balanced and thoughtful, and there is a conceptual link between the songs, which deal with the life of teenagers in redneck America during this era. The album was recorded and released in just two days, and the band were all under 17. Makes this even more of a landmark – or, at least it should have been.