1966 – The Year That Built Rock

Fifty years ago, the world changed for ever – and music was at the heart of it. Out went the squeaky-clean heroes, and in came grubbier anti-heroes. It was goodbye rock’n’roll, hello rock.

Look closely at those numbers. Change and evolution seem to be built into the very graphic shape of 1966. The first two digits pronged into the ground, stable, glancing backwards. The next two on wheels, speeding forward, reaching out and up, one like the hand of Levi Stubbs, the other the windmilling arm of Pete Townshend, pointing the way towards the future. Not just 12 months ahead, but towards where we are now, 50 years later.

1966 was the beginning, the zero hour. The end of teenyboppers and the Scream Age. The birth of serious music fans and the Ear Age. It was the big bang of everything that is celebrated by rock lovers today and by extension, this magazine. Even that word “rock” was new. Shedding its 10-year sidecar “roll”, it became simultaneously more modern and open to all kinds of new sidecar possibilities – acid, folk, freak, garage, psychedelic.

Just consider a few of the still-vital innovations the 1966 rock explosion brought us: the 33 rpm album as a cohesive artistic statement, the guitar hero with the Les Paul and the Marshall stack, the rock opera, the concert light show, the artist who has not only hits but informed opinions about the world, the first live bootleg, and songs that went far beyond boy-meets-girl to explore sex and drugs, disillusion and depression, rebellion and defiance, happenings and higher consciousness. Also, songs that went beyond the de rigeur two minutes 50 seconds. There were multi-track freak-outs like the screaming seagull tape loops (actually a sped-up McCartney laughing) behind the mind-bending Tomorrow Never Knows, and humble-but-hip experiments like the Coca-Cola bottle tapping out time behind Bobby Fuller Four’s Let Her Dance. There was a collision and melding of musical styles and cultures – from the sitars that snaked through Paint It Black to the electrified John Coltrane jazz riffs channelled on Eight Miles High, from the fingerpicked Celtic drones of Roy Harper’s Legend to the amped-up Tchaikovsky of The Move’s Night Of Fear and minstrel show jug’n’jive of Daydream.

That Lovin’ Spoonful song, the biggest hit of the summer in the UK, gave birth to Lazy Sunday Afternoon by The Small Faces, Sunny Afternoon by The Kinks and Good Day Sunshine by The Beatles. That was another magical thing about 1966. Everyone was being influenced by each other, constantly upping the collective creative ante. Paul Simon lent David Crosby a female chorale album called Music Of Bulgaria. Cros said: “Those chicks can sing!” and borrowed some of the harmony magic for Wild Mountain Thyme. Dylan turned The Beatles on to pot, and The Beatles turned Donovan on and he wrote Sunshine Superman. The Small Faces, Spencer Davis Group, The Beatles and the Stones hung out together backstage at the NME Poll-Winners show. “It was euphoric,” said Spencer Davis. There was a unity, a community, all about friendly competition and mutual admiration. Artists were facing the same direction – forward - and suddenly, they were tossing aside those sketchbooks with studies of past masters to create something new on a big, anything-goes canvas.

One of the last major releases of 1965, Rubber Soul, lit the fuse to it all really, introducing the game-changing idea of the album as a deeper experience than the single. Famously, Rubber Soul was the gauntlet thrown down before 23-year old Beach Boy Brian Wilson that inspired him to leave behind the surfboard serenades for the symphonic sound of Pet Sounds, the 1966 album that Andrew Loog Oldham called the “equivalent of Scheherazade, the most progressive album of the year”. But Brian wasn’t the only one who benefitted from dropping the 45 rpm mentality.

Oldham’s charges the Rolling Stones stopped pretending they were living in the Mississippi Delta circa 1930, and for the first time, wrote all their own songs, for Aftermath. Nasty songs they were too, about pill-addicted housewives, groupies and scheming hustlers, set to tough grooves that twisted the blues with marimbas, sitars and Jagger and Richards’ push and pull into what we now know as the unmistakable Stones style. As Richards told Hit Parader in ’66, “Two years ago, our sound was a mixture of Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters. We have our own sound now.”

Dylan defied naysayers and crossed the cultural divide to record in Nashville with a bunch of supposedly square session cats. It turned out they shared his love for amphetamines and intuited how to make his poetry sing louder than ever before. The result was double album Blonde On Blonde, full of brilliance such as the dream-swirled Visions Of Johanna (‘Inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial’ could double as an in-with-the-new rallying call for ’66) and caustic blues of Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat. Dylan even left some revolutionary residue behind. The janitor on those sessions, Kris Kristofferson, would run with Zimmy’s lavish lyricism, mix it with country and turn Music City on its head a few years later.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The gap that Dylan left in Greenwich Village was filled on one hand by The Lovin’ Spoonful, whose ’66 chart run was “hotter than a match head”. Across Bleecker Street was the “Cool town, evening in the city” vibe at artist Andy Warhol’s Factory, where house band The Velvet Underground posed enigmatically with whip dancers and skinny models, blasting out noisy, repetitive songs about whip dancers and skinny models. They were never quite embraced like the cuddly Spoonful, but the Velvets invented the very modern idea of the cult band, that uncompromising act you either hate or adore to the exclusion of all others. And as Brian Eno said: “Their first album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band.”

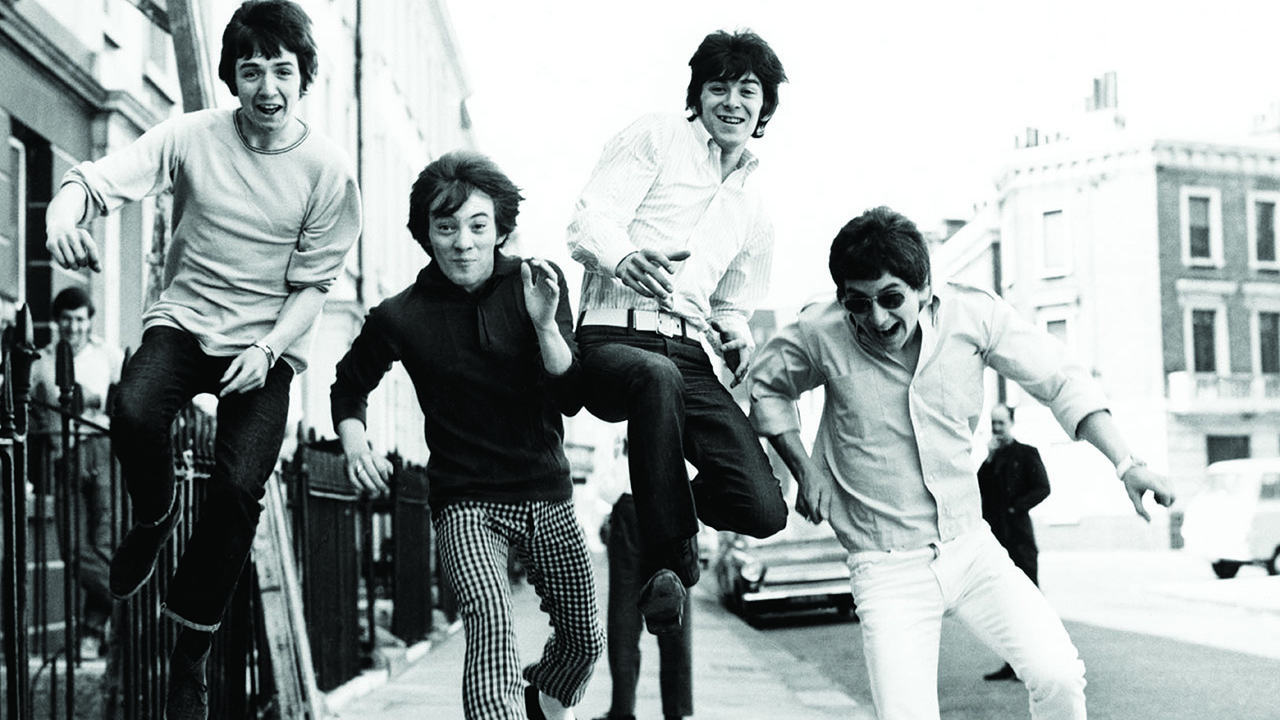

New York may have laid claim to being artistic capital of the world, but in ’66, London was easily its equal. Beatles and Stones aside, it was home to the original and still-greatest guitar-slinging trio ever, Beck, Page and Clapton. But even with the latter’s deity-like status on the rise with Mayall and Cream, he and every guitarist were about to be blown away by a freaky-looking black American lefty named Jimi making his debut at the Scotch of St James. And speaking of freaky-looking, rock stars defined their visual image with the latest fashions, and London’s Carnaby Street was fashion central. It was a bustling scene where you might see Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane checking out their slim-suited reflections in the window of John Stephen’s His Clothes, or doe-eyed, androgynous Twiggy modelling her latest Mary Quant mini-dress.

Other cities were in on the revolution too. Detroit’s Motown was growing restless and adventurous, with ghetto poetry and odes to racial harmony. Across town, Mitch Ryder was sowing the seeds of punk with Devil In The Blue Dress. And two towns over, in Saginaw, Question Mark & The Mysterians were doing the same, hand-delivering copies of the most lascivious one-hit wonder of all time, 96 Tears.

Down south, Memphis and Muscle Shoals were laying gritty groundwork with Otis Redding and Booker T. & The M.G.’s for decades of greatness. Out west, Los Angeles, always a city of light and dark, was harmony fresh with California Dreaming during the day, seedy with Hungry Freaks, Daddy at night. Up the coast in San Francisco (briefly nicknamed “Liverpool of the West” because of the burgeoning scene) experimental author Ken Kesey threw the first of his infamous LSD parties, aka “acid tests,” at the Fillmore, with psychedelic rock band Jefferson Airplane supplying the fuzzed-out soundtrack. And at the hippie church known as the The Avalon, the first trippy light show projected liquid blobs across the laid-back country rock epics of the Grateful Dead.

About that Frisco drug. It opened a lot of neural pathways and inspired a lot of great tuneage in ‘66 – by The 13th Floor Elevators, Love and Blues Magoos. By Donovan and The Byrds. What better advertisement for the drug than Rain and Tomorrow Never Knows? Half of The Beatles’ output that year could be traced to acid. ‘Another road where maybe I could see another kind of mind there’ indeed. In 1966-7 alone, Life magazine estimated a million doses of LSD were consumed. And it was legal for most of the year, which made Harvard doctor Timothy Leary’s credo of “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out” seem like an attractive and reasonable life approach, especially for those skipping along the greener side of the Generation Gap. That overarching idea had been around since Shakespearean times, the phrase itself since the 1920s, but in 1966, when young people discovered the double-talk and duplicity, the hypocrisy and halitosis of the older generation, they seceded to their own island, leaving an ever-widening gulf.

“We want to smash everything; it’s part of what’s happening to us and to our audiences,” said Keith Moon. “Never trust anyone over thirty,” said Free Speech hero Jack Weinberg.

And all rock’s heroes were well under that age. Jagger, Davies, Townshend, Lennon, Clapton, Joplin, Slick, Morrison. Spokesmen and women of their generation. They were bright, sincere, flippant, cynical, hopeful and candid in all the right measures. “Our generation has a lot of idealism but it’s more pragmatic than romantic,” Paul Simon said in ’66. “This is the age of the anti-hero.” Those anti-heroes inspired fans to gaze beyond cars, girls and dancing, and start thinking about deeper subjects – philosophy, politics, religion, social change. Of course, sometimes that intelligence and candor could result in backlash, as in the American south’s overreaction to Lennon’s comment about how The Beatles were “more popular than Jesus Christ” (an event that single-handedly invented serious rock journalism, inspired the first serious rock journal Crawdaddy, and stripped the veneer from the old pop star schtick).

Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner really summed up the essence of the artist and fan dynamic in ’66 when he said: “There’s a significantly greater communication between the music itself, the people who make it, and the people who listen to it, than there was in Elvis Presley’s day.”

1956 to 1966. What a difference a decade made (poor Elvis was stuck in Hollywood-fluff like Spinout). A difference not only in music. A progressive spirit now infused everything. Truman Capote’s riveting In Cold Blood invented the new genre of the non-fiction novel. TV’s Star Trek boldly went promoting racial harmony with a fully integrated crew and episodes about prejudice and tolerance. Twister and Hula Hoops were international crazes, both sneaking sexual freedom into homes and backyards.

Broadway and the West End tackled subjects from prostitution to Communism. Masters and Johnson explored the Human Sexual Response. The first artificial human heart was implanted. The first direct dial international phone calls were made without operator assistance. And the US and Russia launched satellites, dogs and monkeys into space.

Technological and economic changes contributed directly to 1966’s musical progress. Multi-track recorders had been around for over a decade, but they became reliable and streamlined, giving bands four, then eight, then 16 tracks to create their masterpieces. Bigger, louder amplifiers and PA systems jacked up the wattage and excitement at concerts. Solid state technology put portable transistor radios in hands everywhere (the smartphones of their day), and a steady middle class prosperity in the US and UK gave teenagers more spending money for stereo equipment and albums. And $4/£2.75 for an album was a bargain, considering the new release racks were teeming with discs like Fresh Cream, Sounds Of Silence, The Seeds and I Fought The Law.

And the rise of regional indie labels not only gave the latter two purchase on that rack next to major label releases, but forecast how things would look in our future.

Of course, there’d be no 1966 rock – or 2016 rock, for that matter – without the blues. We mentioned the Stones, but this was the year when many bands stopped merely imitating Howlin’ Wolf and Skip James (those two legends both found new audiences in Britain), and discovered ways to transcend the blues. On The Spiders’ Don’t Blow Your Mind, teenage Alice Cooper threw the 12-bar form down a deep well, then yowled up from the bottom in the midst of a fuzz-bass thunderstorm. On Wild Thing, The Troggs lived up to their name by banging a savage caveman sensibility into the catchiest I-IV-V workout ever.

Then there was Shapes Of Things. Next to Tomorrow Never Knows, it may be the most forward-looking song of the year. Pro-environment and anti-war lyrics, a bass riff borrowed from a Dave Brubeck jazz record, a martial beat, abrupt tempo shifts, all capped off with Jeff Beck’s free-form feedback solo.

If there’s one word that sums up 1966, it’s ‘free’. Jimi Hendrix said: “We don’t want to be classed in any category. If it must have a tag, I’d like it to be called ‘Free Feeling’. It’s a mixture of rock, freak-out, blues and rave music.” Frank Zappa said: “We play the new free music – music as absolutely free, unencumbered by American cultural suppression. We are systematically trying to do away with the creative roadblocks that our helpful educational system has installed to make sure nothing creative leaks through to mass audiences.” And John Sebastian said: “As the various categories of popular music break down and mulch, there are what the clerical onlooker calls ‘new sounds’. They are more accurately old new sounds, new old sounds, a free exchange.”

The relentless stream of free, new old brilliance continued right through December, a month that unleashed parting shots of Buffalo Springfield and The Hollies’ For Certain Because. 1967 would grab the relay baton, though it soon ran into a cul-de-sac of too much excess – drugged-out preciousness, 20-minute jams, beads and patchouli. Blech. But as rock moved out of the 60s, matured and glanced in the rearview mirror, it would become clearer that of all years, 1966 remained the one. An example of what’s possible, something to reach for.

Of course, there’ve been many great years since: 1973, 1977, 1979, 1991, to name a few. But let’s face it, we’re still trying to live up to the greatness and the promise of 1966. If a band today makes a record as inventive as, say, Sunshine Superman, it will likely be hailed as a five-star masterpiece. Whereas in ’66, it was just another great record.

As we turn the pages to celebrate the watershed and wheels of 1966, it only seems right to give the last word to the Man of the Year: “Turn off your mind, relax and float down stream, it is not dying, it is not dying.”

Bill DeMain is a correspondent for BBC Glasgow, a regular contributor to MOJO, Classic Rock and Mental Floss, and the author of six books, including the best-selling Sgt. Pepper At 50. He is also an acclaimed musician and songwriter who's written for artists including Marshall Crenshaw, Teddy Thompson and Kim Richey. His songs have appeared in TV shows such as Private Practice and Sons of Anarchy. In 2013, he started Walkin' Nashville, a music history tour that's been the #1 rated activity on Trip Advisor. An avid bird-watcher, he also makes bird cards and prints.