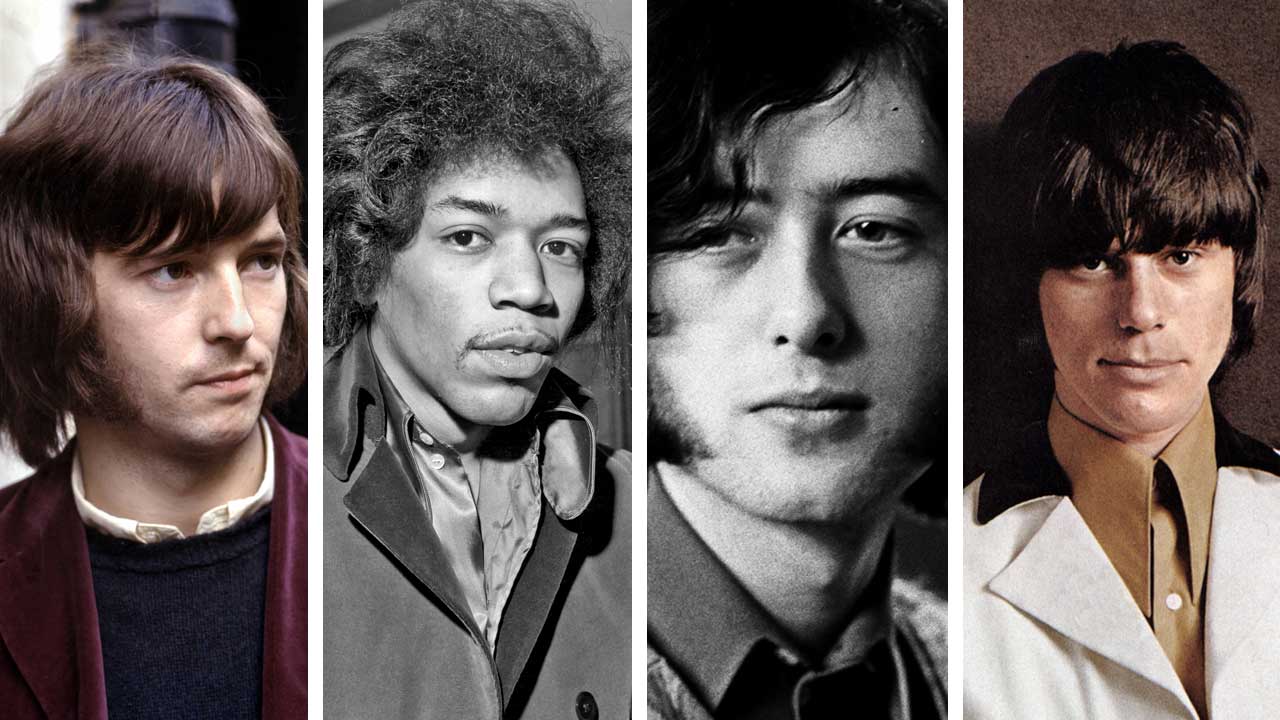

1966 was the year the guitar hero was born. It was the year that Eric Clapton, aged 21, recorded the landmark Beano Album with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and then walked away to form Cream; the year that Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, both aged 22, ended up smashing guitars and bashing through sonic barriers together in The Yardbirds; the year that marked the arrival of 19-year-old wunderkind Peter Green and a game-changing 24-year-old named Jimi Hendrix. It was, in short, the year when a new generation of guitar giants transformed the American deep blues songbook into a new strand of rock music.

Things were happening at a grass roots level too. The British R&B/blues circuit was a hothouse for new musical talent, many of them the stars of the future. Steampacket featuring Rod Stewart, Julie Driscoll and Long John Baldry, an amazing triumvirate of singers, along with the organist Brian Auger, was one such band. Ten Years After, boasting the speed-king Alvin Lee, Chicken Shack with the wiry blues warrior Stan Webb, and The Paramounts with apprentice guitar hero Robin Trower criss-crossed the country in their Commer van, playing a network of clubs, bars and town halls that stretched from the Club A’Gogo in Newcastle to the Florida Rooms in Brighton.

“There was an underground feeling in the air,” John Mayall says of the period just before the Beano Album came out on July 22. “The people in the clubs were flocking to see us, regardless of what was happening in the record business or the pop charts. We were playing to capacity crowds, six or seven nights a week, everywhere we went. So we figured something was about to happen.”

And happen it did.

The electric guitar has always been part of the British pop dream. At the start of the 1960s, the immaculately groomed Hank Marvin and the Shadows, with their gleaming red Stratocasters, gave way to a wilder breed of player with the arrival of Keith Richards and Brian Jones.

The Rolling Stones themselves had been mentored at the outset by the bandleader/guitarist Alexis Korner and harmonica player Cyril Davies, who had introduced the blues to jazz audiences when they formed Blues Incorporated in 1961. The players who passed through the line-up of this loose collective included Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker and Charlie Watts, while those who made guest appearances with the band on their regular Rhythm and Blues Nights at the Ealing Jazz Club included Mick Jagger, Mayall and Page.

By the start of 1966, Korner was about to wrap up Blues Incorporated and – at the grand old age of 38 – embrace his well-earned status as an elder statesman of the R&B scene he had done so much to inspire. All around him his protégés were flourishing. In the pop charts the Stones were second only to The Beatles, while R&B-influenced bands such as The Animals from Newcastle and the Spencer Davis Group from Birmingham were dominating the airwaves on the ever-more popular pirate radio stations.

Foremost among the British blues pioneers who had followed the Stones into the world of pop stardom were The Yardbirds. Their album Five Live Yardbirds, released in December 1964, was an early prototype of the blues rock genre, thanks to the advanced musicianship of the band, and in particular that of its young lead guitarist, Eric Clapton. Although poorly recorded, the album’s wild-eyed versions of Smokestack Lightning, I’m A Man and others provided a template for the instrumental wig-outs that two years later would become the stock-in-trade of Cream and many other groups that emerged in their wake.

Clapton’s tenure with The Yardbirds ended abruptly in March 1965 when he deemed the group’s first hit single, For Your Love, to be insufficiently bluesworthy for him to be associated with. He was replaced by Jeff Beck, another supremely gifted guitarist with a similar art school background and fascination for the blues, but a more mercurial and experimental nature.

By the start of 1966, The Yardbirds had already travelled a long way from their blues beginnings. In February, they released the pivotal single Shapes Of Things. With its bold, philosophical lyric and Beck’s heavily distorted guitar solo, it found them exploring new frontiers of psychedelic pageantry. “We were all on the threshold of this new thing,” Beck later said. “The Yardbirds were the very first psychedelic band, really.”

But back in the clubs, bars, town halls, student unions and speakeasys of the UK, Alexis Korner’s legacy was clearly in evidence. There, a dedicated cadre of young musicians immersed in the history and artistry of the blues played to fans rammed into smoke-filled rooms who spread the gospel further afield with every day that passed. Like a gathering storm, the blues was about to break.

“It all happened very quickly,” recalls Mayall, who had relocated from his native Manchester to London, and by the start of 1966 had taken over from Korner as the torchbearer of modern blues in Britain. “British audiences had been listening to trad jazz for ten years, and a new generation was ready for something new. There was a really great energy that suddenly came about.”

Nowhere was that energy more concentrated than in the latest line-up of Mayall’s Bluesbreakers that featured John McVie on bass, Hughie Flint on drums and Eric Clapton on guitar, who Mayall had snapped up as soon as he’d left The Yardbirds.

On January 1, 1966 the Bluesbreakers saw in the New Year playing an all-nighter at the Flamingo in Soho, the first date on a gig sheet that already stretched ahead with few breaks into the months ahead. The Flamingo, a basement club in Wardour Street, was run by brothers Rik and Johnny Gunnell. Rik, an ex-boxer and bouncer, was also Mayall’s booking agent, and the venue was a colourful R&B mecca – “semi-dubious”, according to Mayall – where gangsters and prostitutes rubbed shoulders with jazz and blues musicians.

“Everybody knew everybody, because we were all playing the same circuit,” Mayall says. “Everybody was all part of one big family, if you will. We were all really surprised to discover that we could actually earn a living out of this music.”

For Mayall it was all about playing live and keeping together a band that could handle the workload. “The club scene was rolling for everybody,” he recalls. “There was so much work going on. There was enough for everybody.”

The bigger bands had a driver but there was no road crew. Drummer Aynsley Dunbar, who joined the Bluesbreakers in September 1966, remembers it as a time when road and vehicle safety were not the best, when nobody wore seatbelts and a new law prohibiting drinking and driving was passed in January 1966 but it was rarely enforced.

“I couldn’t sleep when I was being driven,” Dunbar recalls. “There were so many drivers around who’d had a drink or were too tired, and there were a lot of crashes so, over the years, I used to do a lot of the driving myself. I loved it! My average speed was always a hundred miles per hour or a bit more. We had some near misses.”

When the band got to the gig they would have to unload and set up the gear themselves. Mayall’s equipment included a Hammond organ that took some manhandling. “I fashioned some wooden handles and fixed it up like a sedan chair with a couple of poles running through the organ,” Mayall explains. “Two guys could navigate most of the venues like that, whether it was down to the basement at the Flamingo or up a flight of stairs in some cases.”

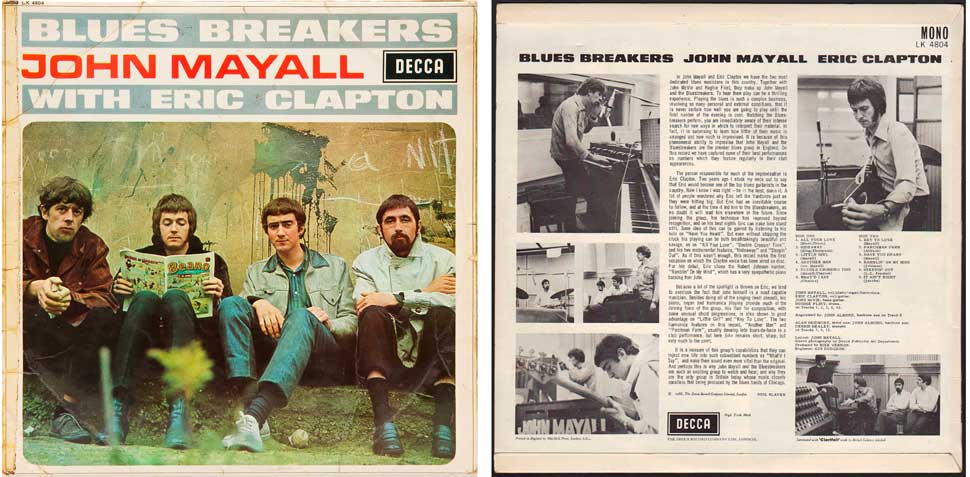

Mayall’s first album, John Mayall Plays John Mayall, released on Decca in 1965, had sold less than 1,000 copies and he had accordingly been dropped from the label. A succession of singles fared even worse, and it was only thanks to the persistent lobbying of producer Mike Vernon that Decca countenanced recording and releasing the Beano Album.

No one in the business was expecting the thunderbolt that arrived in the summer of ’66. But Clapton’s street reputation was already a phenomenon, and at least one tastemaker with a spray can had declared ‘Clapton Is God’ on a wall in Islington, North London. It was a measure of the young guitarist’s charisma and ability that such an outrageous tag stuck. And it was a measure of the brilliance of the album, formally titled Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton – but known as the Beano Album after the comic that Clapton can be seen reading with effortlessly cool insouciance on the cover – that it exceeded all precedents, never mind expectations.

The Beano Album raised the bar in modern recorded music overnight. From the opening notes of All Your Love, in which Clapton’s distinctive vibrato and steely tone slice through the mix like a guillotine, the sound and performances on the album were – and still are – superlative. The combination of Clapton’s Les Paul and an overdriven Marshall amp became the new template for a cool electric guitar sound and one that has rarely been bettered in the 50 years since.

“Eric’s contribution was quite phenomenal,” Mayall says. “He was the best there was. He wanted to play the blues and I provided a platform on which he could develop that.”

Mayall’s own routines on the harmonica-driven tracks Parchman Farm and Another Man were no less remarkable for their raw, gutbucket energy, while his howling vocal call on the Mayall/Clapton composition Double Crossing Time echoed the ghosts of blues singers down the years.

More than just a stunning blues collection, the Beano Album was the first de facto rock album. It featured nothing so commerical as a hit single, yet it reached No.6 in the UK. Its unexpected yet emphatic success was a key moment in the process whereby albums started to take over from singles as the barometer of a band’s success.

With its revolutionary sound, its reverence for the nuances of electric Chicago blues, its spiritual vigour and technical rigour, the impact of the album was seismic. A generation of guitarists had just received the wake-up call of their careers, and within a year the British Blues Boom would be in full swing.

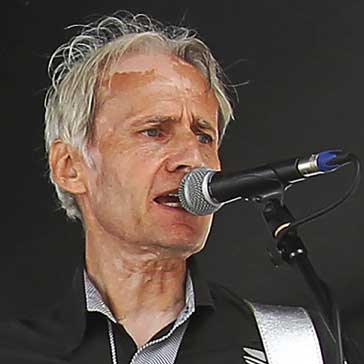

For Mayall it was simply business as usual. “The record business was something we had no control over,” he says matter-of-factly. “But we did have control over getting our weekly quota of shows. The main focus for me was to keep the band together – or some line-up of the band – so that we could continue to go out and play.”

For Clapton, however, the Beano Album was instant history. By the time it was released he had already left the Bluesbreakers. Things happen fast when an art form is at a pivotal stage of its development, and Clapton was a young man driven by the same urgency of feeling that you could hear in his playing. On July 30, the day that England won the football World Cup, and just eight days after the Beano Album was released, Clapton, Bruce and Baker played their first gig together as Cream at the Twisted Wheel in Manchester.

Bruce had played with Clapton in the Bluesbreakers for a stretch the previous year, and on one occasion Baker had sat in. “That was when Eric, Jack and Ginger got talking in dark corners about their own futures,” says Mayall, who was remarkably unfazed at the prospect of having to carry on gigging without the star of an album that had just reached the Top 10. “For me it’s never been a problem,” he says. “Somehow or other I’m always able to find somebody else and make a different band.”

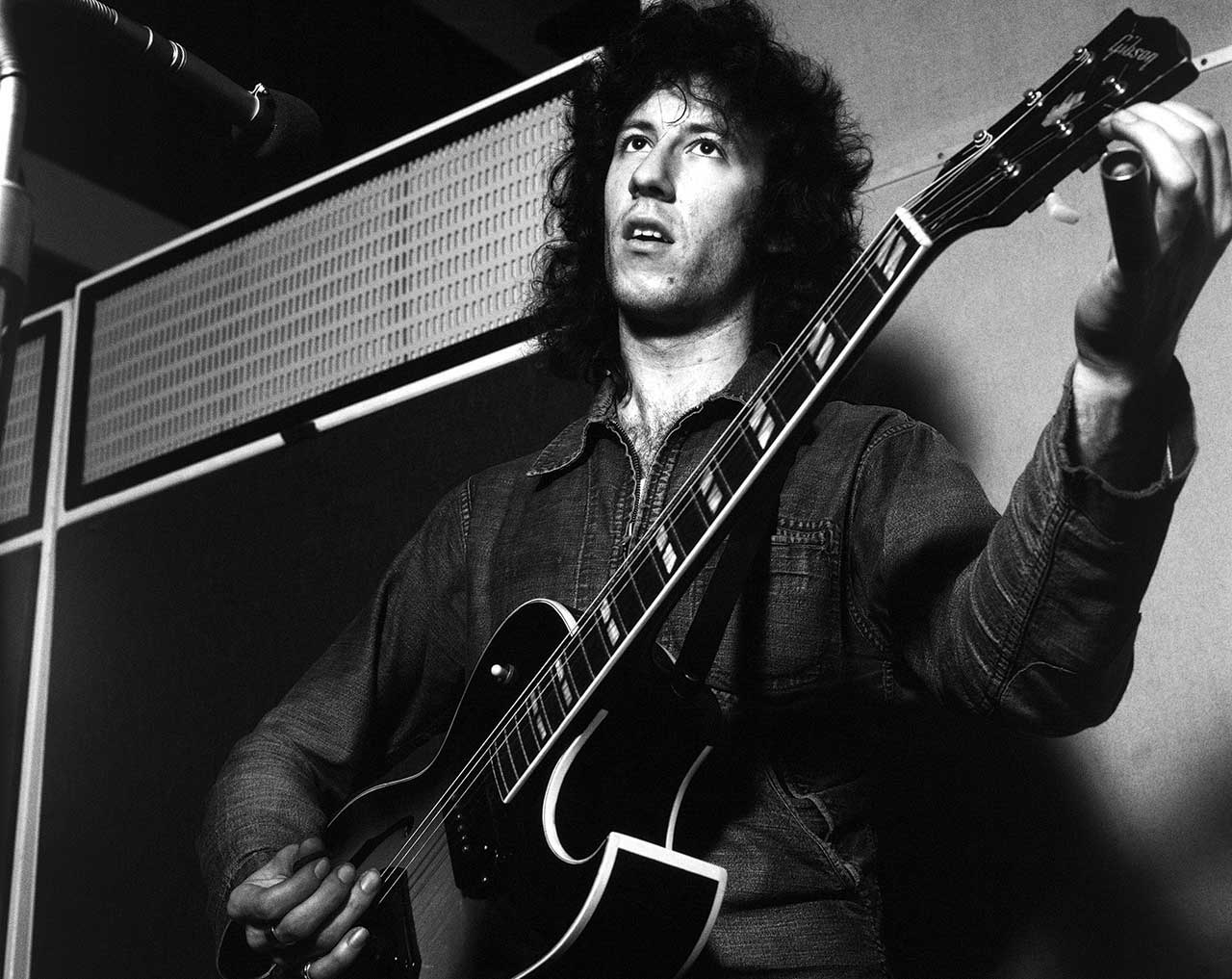

Clapton’s replacement was Peter Green, another blues prodigy from East London, who had deputised for Clapton in the past. “It took me a while to talk him into it,” Mayall recalls. “He’d been offered a job to tour America with The Animals. But in the end the music won out. He decided he’d rather play blues than go off to the States.”

In September, Hughie Flint also called it quits and Mayall was now on the lookout for a new drummer. He spotted Aynsley Dunbar playing a gig with Alexis Korner at a venue called Les Cousins in Wardour Street, and invited him to come and check out the Bluesbreakers a couple of days later at a gig at Chelsea Town Hall.

“They came on stage and Peter Green started with three notes and I just fell in love with the band right there and then,” Dunbar recalls. “His playing was just so soulful. It wrenched me apart. I couldn’t wait to play with them.”

He didn’t have to. Mayall instructed him to report for duty the following day and the drummer played his first gig as a member of the Bluesbreakers at Norwich Town Hall that night. He played six or seven gigs a week for the next six months. “There were no rehearsals,” Dunbar recalls. “All rehearsals were done on stage in front of an audience – or you might get a run through before doing a take in the recording studio.”

There was also the small matter of recording the band’s next album, A Hard Road, which was completed over four days in October 1966 at Decca Studios in West Hampstead. As with the Beano Album before it, A Hard Road was a showcase for the band’s new guitarist.

While Clapton, Beck and Page shared similar backgrounds, Peter Green was unlike any of them, indeed unlike anyone else on the scene. A quiet, contemplative man from a Jewish family, he took up the guitar after he first saw Clapton, whom he idolised, playing in The Yardbirds. Where Clapton (and Beck’s) playing was driven by an insistent, aggressive urgency, Green’s playing (and singing) style had a more emotional elegance that tapped into the mournful quality of the deepest blues.

Green’s instrumental composition, The Supernatural, built around a single, spine-tingling sustained note, was one of the most haunting pieces that Mayall ever recorded - and Out Of Reach, an achingly sad song composed and sung by Green (not on the original album, but released as a Mayall B-side around the same time), was simply one of the most soulful recorded performances by any blues act of this era.

“I can say without hesitation that Peter Green was the most brilliant musician I have ever played with,” said Mick Fleetwood, who played drums in the Bluesbreakers after Dunbar left in 1967 and later formed Fleetwood Mac with Green. “He could be running through a blues progression we all knew, one that we’d heard a million times, but when Peter played it those same old notes sounded brand new.”

While Green was recording A Hard Road, and Clapton was gigging and recording his debut album with Cream, the era’s two other great guitarists were about to be immortalised on the big screen. Between October 12 and 14, The Yardbirds were at Elstree Studios, where the Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni was making his film Blow-Up, a murder mystery-cum-social snapshot of Swinging London. The script called for a cameo from a rock group who would sum up the nihilistic, countercultural energy that was rippling through the capital’s musical psyche in 1966, and The Yardbirds were it.

It had already been a turbulent year for The Yardbirds, whose bassist Paul Samwell-Smith had left the group in June and been replaced by session guitarist Jimmy Page. Page and Beck had known each other since they were teenagers, and enjoyed a lively relationship delicately balanced between respect and rivalry. Page was never going to be anyone’s bass player for long, and switched to guitar the first chance he got.

The new line-up (with Chris Dreja on bass) had just finished a tour with the Rolling Stones and Ike and Tina Turner when they got the Blow-Up gig. Antonioni filmed them playing Stroll On, a rocked-up version of an old American jump-blues song Train Kept A-Rolling, on a stage set that replicated the Ricky Tick Club (actually in Windsor rather than the capital) in every detail, right down to the chewing-gum on the chairs.

“Antonioni was an awkward bastard,” Beck later recalled. “He says to me: [adopts Italian accent] ‘We want you to break your guitar.’ I said: ‘Oh yeah? A 1954 Les Paul and you want me to smash it? Get away.’ He said: ‘Don’t be ridiculous, we pay for it.’ I said: ‘You can’t replace that.’ So then they got Höfner to bring down these shitty guitars. So I had this tea-chest full of these twenty-five-quid joke guitars. They were just destined to be smashed, and I went right through ’em three or four at a time with this Höfner rep standing watching at the side. He thought it was all great fun.”

This was a good day’s work for The Yardbirds. Blow-Up was hailed as a masterpiece and became one of the biggest-grossing films of the year in America. As a means of rubber-stamping the concept of the British guitar hero for an international audience it could hardly have been bettered. But according to the band’s manager, Simon Napier-Bell, the experience of making the film gave Beck a taste for smashing up equipment on stage during the group’s ensuing US tour, which proved destructive in other ways.

“Gig after gig he tottered round the stage, ramming the neck of his guitar through the speakers and crashing his feet into the delicate electrical controls. I was left a prisoner in my suite at the Chicago Hilton, phoning round America trying to find the location of every Marshall amp in the country and chartering planes to fly them to the next evening’s gig, only to be destroyed by another night’s bad-tempered Beck-ing.”

The expenses mounted, and relations between Beck and the rest of the band soured until, three-quarters of the way through the tour, Beck left the group, pleading “inflamed brain, inflamed tonsils and an inflamed cock”.

Beck was duly booted out of the group in November. Page took over and began a process of ramping up the grandstanding performance elements with a violin bow during increasingly extended solos, and laying the foundations for the his next band, the New Yardbirds. Within two years he had changed their name, and Led Zeppelin were born.

The emergence of the Thames-delta guitar hero as an icon of popular culture was almost complete when the most exotic creature of all landed in their midst. Jimi Hendrix arrived unknown and unheralded in London on September 24. With the help of his manager Chas Chandler, he began sitting in with just about every band in town – including the Bluesbreakers and Cream – while recruiting an English rhythm section to be his band. Dunbar was one of the drummers who auditioned for him.

“We were perfect together,” Dunbar says of this encounter with Hendrix. “Later, when I had my own band [the Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation] Hendrix would jump on stage and play with us every time we played at the Speakeasy. One night, he just poked his guitar through the ceiling.”

Be that as it may, Dunbar didn’t get the job with the Experience. The story goes that Hendrix and Chandler tossed a coin to choose between Dunbar and the man who got the job, Mitch Mitchell.

“I’ve got to clarify that,” Dunbar now insists. “They were offering me twenty pounds a week to play with Jimi. I said: ‘Give me thirty a week and I’ll be there.’ It wasn’t a toss of a coin. They were just trying to be cheap.”

Presumably Dunbar was making more than £20 a week playing with the Bluesbreakers. According to Napier-Bell, bands such as The Yardbirds and The Who could command a fee in the UK in 1966 of £350 a night (about £4,500 in today’s money). Setting the gold standard, the Stones would go out for a fee of £450 (£5,800) and The Beatles – who played their last live concert, at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in August ’66 – would have been charging “around a thousand pounds” (£13,000).

A year of freewheeling creativity ended with two of the most significant rock releases of the decade. The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s debut single reached the shops on December 16. Hendrix’s cover version of the old murder ballad Hey Joe and its B-side Stone Free was a harbinger of a revolution to come.

Released a week earlier, Cream’s debut album, Fresh Cream, was a game changer in much the same way that the Beano Album had been six months previously. Applying a skill-set that was more akin to that of the great jazz improvisers than to pop musicians, Clapton, Bruce and Baker made an incredible opening statement, full of mind-bending harmony vocals and unprecedentedly extravagant soloing on guitar, harmonica and drums. Blues rumbles such as Willie Dixon’s Spoonful and Skip James’s I’m So Glad were turned into monumental instrumental workouts, while original compositions such as N.S.U. and Sweet Wine redefined the parameters of a rock genre that had only just been defined in the first place.

It was an astonishing album with which to bring the curtain down on a year during which the skill of the guitarist had for the first time been elevated above the appeal of the singer, and the skill and daring of one guitarist in particular – Clapton – had been elevated above that of all others.

Rock was finally rolling.