The first time Dave Jerden heard Alice In Chains, he thought they were a mess. It was 1988, and Dave, who had just produced Jane’s Addiction’s groundbreaking Nothing’s Shocking album had been given the band’s demo tape by an A&R friend at Sony. Despite the growing buzz surrounding their hometown of Seattle, the band’s music was all over the place, and no producer wanted to touch them. But there was one song in which he heard the sound of the future.

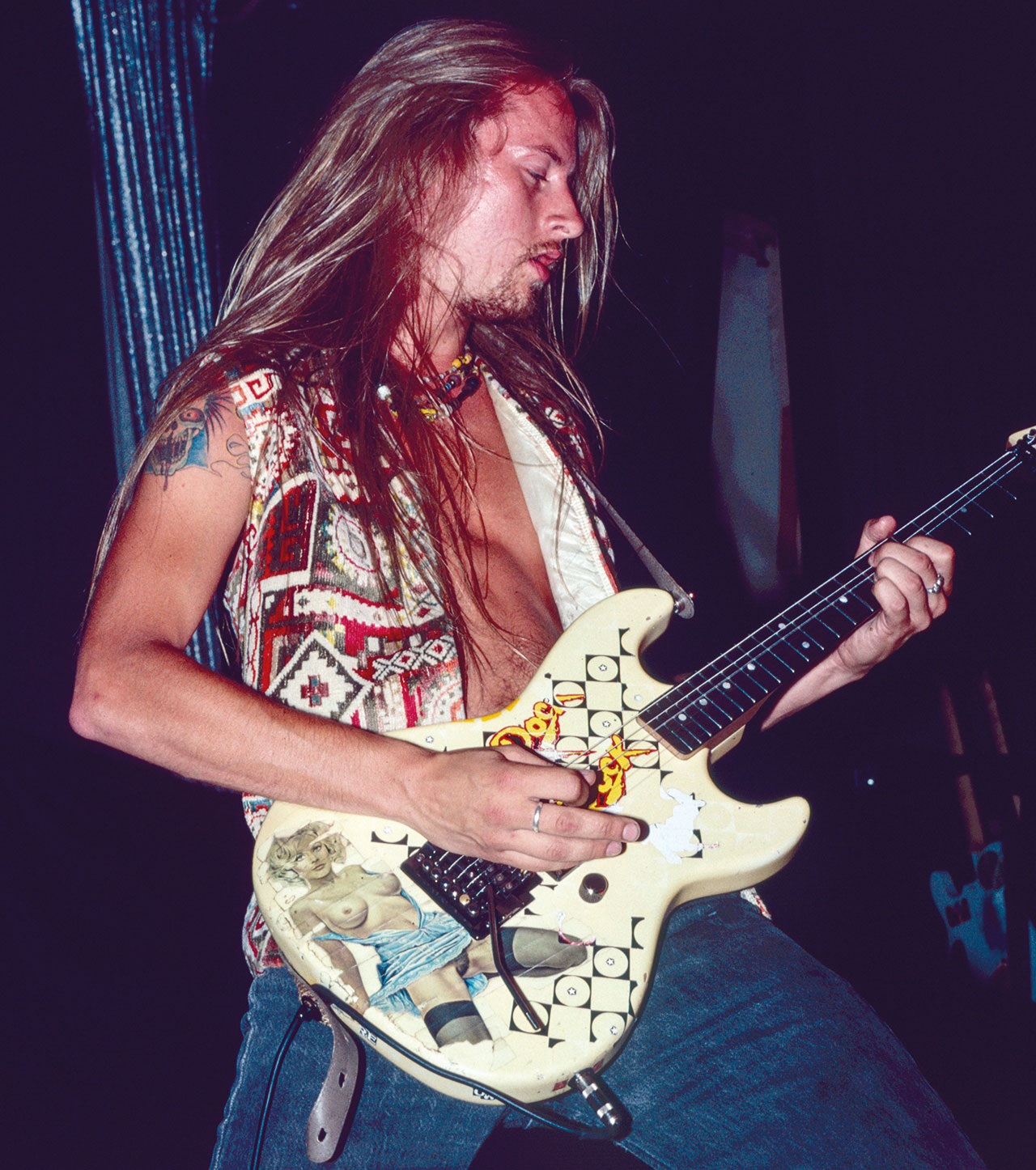

“I forget which song it was, but it was the closest to the Alice In Chains we know now, with the drop-D tuning,” says Dave today. “I met with the band and told them what I thought, that their songs were a mess. But I also said to Jerry Cantrell that I liked what he was doing. It was like if Metallica had sped Tony Iommi’s riffs up, then brought them back down again.”

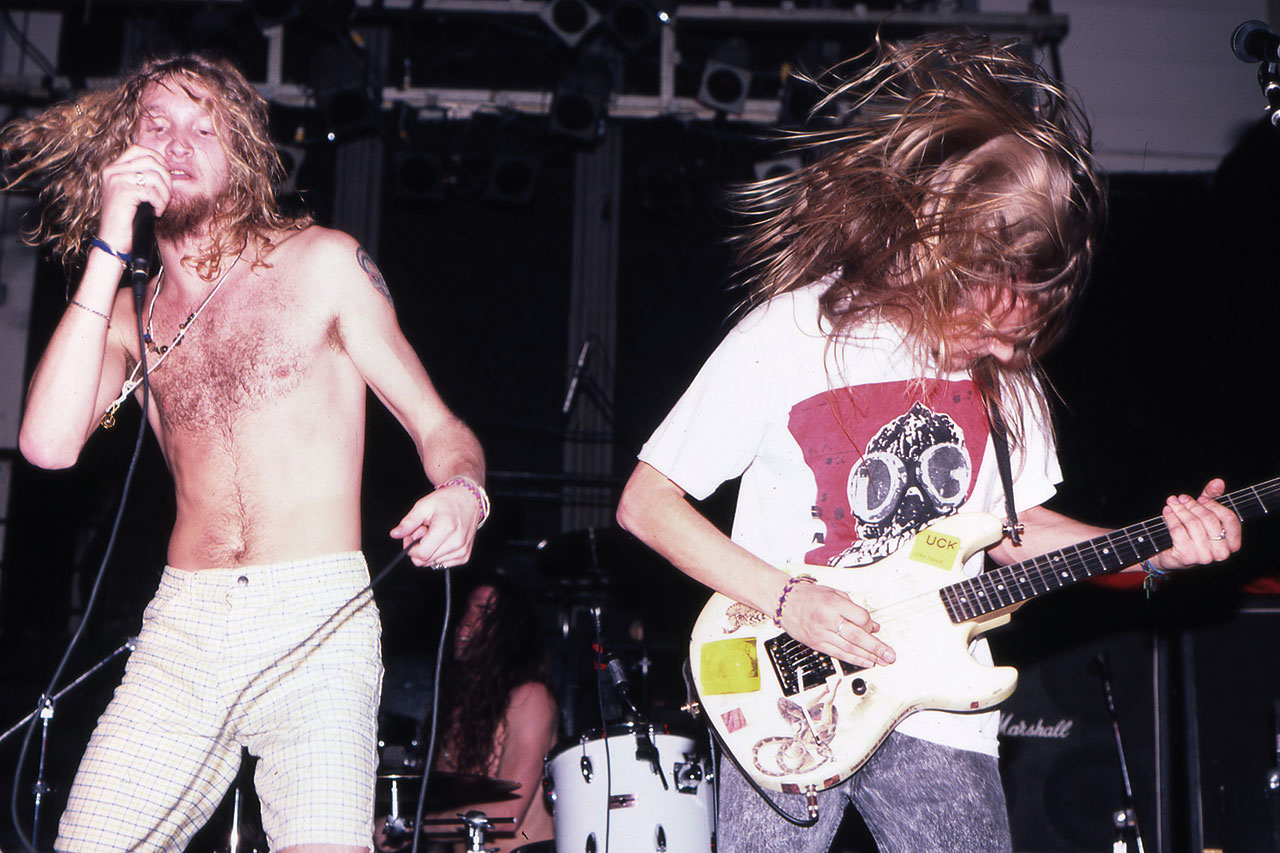

Dave’s foresight was bang on the money. Within 18 months, Alice In Chains had leapfrogged the likes of Soundgarden and Nirvana to become grunge’s first superstars. With their debut album, Facelift, they became the first band from the Seattle scene to sell half a million records, opening the door for everyone to follow. And in Layne Staley, they had a truly iconic singer: tortured, charismatic, ultimately doomed.

“Facelift was where Alice In Chains found their style,” says Dave Jerden. “And Man In The Box was the first song that introduced the world to the grunge sound. It was never a case of luck. That record was meant to be.”

When Jerry met Layne, grunge was barely a twinkle in Kurt Cobain’s eye. It was 1987, and the top dogs of the Seattle scene were prog-metal pioneers Queensrÿche and B-list thrashers Metal Church.

Layne and Jerry had chequered musical pasts – the former as the singer of glam metal band Sleze, the latter as guitarist with bouffant-haired rockers Diamond Lie. But they had plenty in common. Both had troubled backgrounds. Jerry’s mother had died of cancer when he was young, and he wasn’t close to his father. Layne had been kicked out of his house by his mom. They bonded over family, drugs and music.

“We met at a party,” Jerry told author Mark Yarm in the book Everybody Loves This Town. “I didn’t have a place to live so he invited me to this place where he lived called Music Bank. He was just such a cool fucking guy and his voice was amazing. I knew I wanted to be in a band with him right off the bat.”

The pair stumbled through various combinations of band names before settling on Alice In Chains, borrowed from a name Layne’s old band had briefly used. The line-up was completed by bassist Mike Starr and drummer Sean Kinney.

Their demo, The Treehouse Tapes, ended up in the hands of Nick Terzo, an A&R man with Columbia Records, who signed the band. Nick passed it on to Dave Jerden, who told the band they should go in and record another demo. A few months later, Dave received a new six- track tape. One of the songs was Man In The Box, destined to become AIC’s breakthrough hit.

“When I got that six-track demo, and it had Man In The Box and all the great songs from that first album, that’s when I really thought we could be on to something.”

Dave travelled up to Seattle to start working on Alice In Chains’ debut album. The band took him out to the local clubs, where he saw grunge pioneers such as Soundgarden and Mother Love Bone. “You could tell that something was in the air,” he says. “I had kind of been aware of this ‘Seattle sound’ that people were talking about, but to be there felt very exciting.”

Not that Alice were entirely accepted by their grunge peers. Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil recalled their early demos “owed a little bit more to Poison”. He claimed that the band changed their approach when they heard Soundgarden. “Jerry asked me how to play songs like Beyond The Wheel [from Soundgarden’s 1988 debut, Ultramega OK],” he remembered. “I said, ‘There’s this thing called drop-D tuning. A short time later they recorded a demo of the songs you hear on Facelift and they had that drop-D tuning on them.”

Work began on Facelift at London Bridge Studios, out in the woods a long drive from the centre of Seattle. Despite Layne’s escalating drug use, the problems were physical rather than pharmaceutical.

“Sean Kinney had broken his arm and couldn’t play,” recalls Dave. “We got the drummer from Pearl Jam to cover him but he couldn’t do it, so Sean played on that record with a broken arm.”

The darkness that would descend on Alice In Chains was still a way off. Dave remembers there being a real camaraderie between the bandmembers. “Those guys came from the same sort of crazy backgrounds, and they banded together like a family,” says the producer.

“We’re all outcasts,” Jerry later told Spin magazine. “We just want to be able to look each other in the eye and go, ‘This is pretty cool.’ That’s all you need – everybody grooving on the same thing.”

Songs such as Man In The Box, We Die Young and Bleed The Freak were shot through with dark imagery, but the band subsequently denied they were about drugs or the attendant lifestyle. Layne claimed that Man In The Box was inspired by mass media censorship, while Jerry claimed We Die Young came about after he spotted a gang of pre-teen drug dealers on the way to rehearsals. “Seeing all these 9, 10, 11 year-old kids with beepers dealing drugs equalled ‘We died young’ to me,” he wrote in the liner notes to 1999’s Music Bank box set.

“I believe that Layne was a sensitive person attracted to darkness,” Dave shrugs, “but I never saw any evidence of drugs in the studio. Not once. I believe that on Facelift, Layne was portraying a dark world from the outside looking in. It’s only later t hat they were right inside it looking out.”

We Die Young was released as a radio single in July 1990, and Facelift followed a month later. It sounded like nothing else at the time. Black Sabbath were seen as an over-the-hill joke by the turn of the 1990s, and few bands wore their influences as openly as Alice In Chains. Even more unique were Layne and Jerry’s intertwined harmonies, either heavenly or hellish depending on the song. But with grunge yet to take root in the broader public consciousness, it was a tough sell, as the band found out first hand.

The Clash Of The Titans was one of the landmark heavy metal package tours of the early 90s. The US leg kicked off in May 1991 and featured Megadeth, Slayer and Anthrax. San Francisco thrashers Death Angel were due to open, but cancelled following a tourbus crash. Enter Alice In Chains – not only a relatively unknown name, but not even a thrash band.

“They were out there in front of 15,000 Slayer, Anthrax and Megadeth fans that were pelting them every night with crap,” recalled Anthrax guitarist Scott Ian. “But they never let any of it get to them. And then of course, Man In The Box broke and all those people that were throwing beer cups at them went out and bought their record. So Alice, they got their revenge.”

Released in spring 1991, Man In The Box was a slow starter. “At first, radio wouldn’t touch it because they said that Layne’s voice was wrong,” says Dave. “It was just a station in Texas that put it on syndication and the reaction was wild, so everyone followed suit.”

MTV eventually picked up on the song, and Facelift started to rapidly gain traction. Having sold just 40,000 copies in its first few months, it shifted more than 400,000 copies in six weeks on the back of Man In The Box. Before Nirvana, Pearl Jam or Soundgarden, Alice In Chains had become the first of Seattle’s grunge bands to crack the mainstream.

There was still plenty of work to do. Shortly after their Clash Of The Titans stint, Alice began a lengthy, 60+ date tour opening for hard rock legends Van Halen. It was towards the end of that run that Dave Jerden reconnected with his former charges, only to find them in a very different state of mind.

“I went to see them just before we went in to do [Alice’s second album] Dirt,” says the producer. “I asked them, ‘What’s it like to be famous?’ and they all said, ‘We hate it.’ Especially Layne. He said, ‘People treat you like an object. They just want a piece of you.’”

The singer was dealing with his own demons. He was deep in a heroin habit that would last until the end of his life. It made the atmosphere in the studio very different to when Dave and the band began work on Dirt.

“Something had happened to that family,” says Dave. “It was drugs, that was obvious. Layne started recording a week after getting out of rehab. They suddenly seemed to be living the darkness that they were only exploring on songs like We Die Young from the first record. That’s what they wanted, but you have to be careful what you wish for, I guess.”

Dirt was an altogether darker record, and the true starting point for Alice In Chains’ – and especially Layne’s – descent into hell. There were moments where the darkness lifted – most notably the band’s stellar MTV Unplugged show – but the lights went out completely when the singer backed away from public life in 1996.

Today, Alice In Chains stand as one of the great bands of the 90s. Dirt rightly stands as their masterpiece, but Facelift is no less important. Without it, the 1990s could have been very different.