2015 - The Burning Questions: Is Everything Alright With Lemmy?

Gigs cut short, tours cancelled, hospitalisation – the world is concerned for the ultimate rock warrior. But Lemmy insists he’s going nowhere…

For Motörhead, 2015 was a year of triumph and disaster. Forty years after they formed, the band that everybody wrote off as stillborn back in the summer of 1975 released their 22nd album, the acclaimed Bad Magic. Their relentless march onwards was down to the stubborn tenacity of one man.

Motörhead have been Lemmy’s life’s work: part Boy’s Own tale gone gloriously wrong, part speed-fuelled party, part “fuck you” to the world. Along the way he has created some of the most brilliantly essential music ever written, while his unique mix of wit and orneriness has turned him into a weird kind of celebrity – one that even your granny knows. No wonder that a 2011 documentary of his life was titled 49% Motherfucker, 51% Son Of A Bitch.

But 2015 was also the year in which it seemed like the story was reaching an end. That documentary showed Lemmy saying goodbye to pints of Jack Daniel’s ’n’ Coke, cigarettes and fried food, the change of lifestyle down to the onset of diabetes. In 2013 he admitted that he’d been fitted with a defribrilator after being hospitalised with an irregular heartbeat. Life was telling the poster boy for rock’n’roll excess to slow down – and he didn’t like it. “People insisted: ‘You’ve got to stop smoking, Lem,’” he told Classic Rock. “My response was: ‘Fuck you.’ I hate people telling me what to do, even if they might be right.”

The extent of Lemmy’s problems became apparent at the Wacken Festival in Germany in 2013, when Motörhead were forced to cut short their set after just six songs due to Lemmy’s health issues. A subsequent European tour was cancelled. The band made it back on stage in July 2014 to support Black Sabbath in London’s Hyde Park, where they limped through a 50-minute set that included a drum solo after just five songs. An appearance on the main stage at that year’s Glastonbury festival prompted The Guardian to compare him to Iron Maiden’s mascot Eddie, and described him as “a slurring, gargling rock wreck”.

Bad Magic, released in August, sounded like the work of a revitalised band. But hopes that Lemmy’s problems were behind him were crushed when Motörhead were again forced to abandon a show in Salt Lake City, with Lemmy citing breathing problems caused by altitude sickness. A few days later, in Austin, Texas, it happened again. Just three songs in, Lemmy made the emotional declaration: “I can’t do it.” Video footage of him returning to the stage to announce, “I would love to play for you, but I can’t…” added to how upsetting it was. When they did make it through to the end of their 13-song set, in St Louis on September 8, guitarist Phil Campbell raised Lemmy’s hand high, like a victorious prizefighter.

Lemmy is not stupid. He knows what people are thinking, and he’s clearly bored of talking about it. Still, when I speak to him to find out exactly what’s going on, the early signs are not encouraging. That unmistakable growl is still there, but he sounds breathless at times. Where once he was an enthusiastic conversationalist, today he’s quieter and more concise. His sentences trail out with more “you knows?” than they used to. He sounds weary.

The most important question is: how are you?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Oh, that’s getting really old, that question. I’m alright. I’m going out there [on stage] and doing my best. I have good days and bad days but mostly I’ve been doing alright. The last tour of the States was very good.

Obviously, ahead of a British tour, we have questions about your health and well being. It sounds like you’re not going to like them.

Well, I’m sick of the fucking ‘Are you going to die?’ line of questioning.

Okay. But given what’s been happening with Motörhead, it’s to be expected that people want to know how you’re getting on.

I’m getting on alright. In a day-to-day sense. I can’t make a generalised statement about how I am because it changes.

How is all this affecting the other two band members, Phil Campbell and Mikkey Dee?

Oh, they’re alright.

But they must be as concerned as the rest of us?

Well, they’ve been in the band for a long time, you know? If I have trouble doing the gig, they understand.

You’re a very proud guy. It must have torn you apart to cut short those shows in Salt Lake City and Austin.

I am, and it did. But what can I do? I’ve got to work. And being in a band you’ve got to play on stage. That’s how the thing works.

It’s strange to think about Lemmy’s current situation. The old joke is that in the event of a nuclear war, the only survivors will be the cockroaches and Lemmy. His legend is that he’s indestructible. “Lemmy will live until he’s a hundred,” says Saxon’s Biff Byford, a long time friend whose band supported Motörhead on their troubled US tour. “The guy is a fucking robot.”

Only Lemmy isn’t a robot. He’s a man who turns 70 on Christmas Eve; someone who is as prone to the ravages of time as the rest of us. Sometimes that lived-in persona and those tales of debauchery get in the way. We’ve come to celebrate Lemmy as a living, breathing embodiment of the rock’n’roll ethos – partly because he made it look so easy.

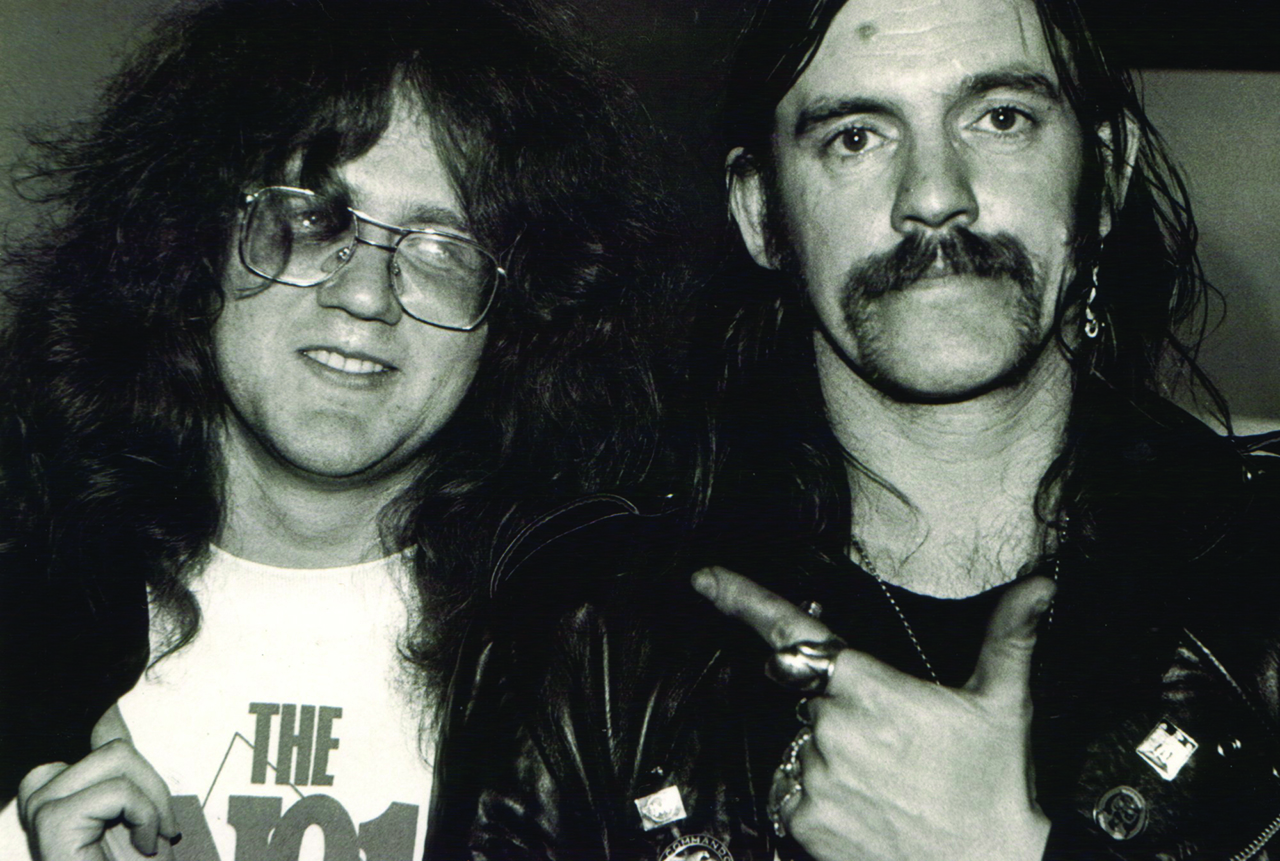

It’s difficult to believe that I first met him in 1980, when a friend and I bunked off school to visit the band’s management office near his stomping ground of Ladbroke Grove, hoping to exchange an ill-fitting T-shirt bought on the Bomber tour. Little did we know that it was the day Motörhead and Girlschool were recording the promo video for their cover of Johnny Kidd & The Pirates’ Please Don’t Touch, and we were shocked and delighted when both bands suddenly arrived. There was no time for autographs, but Lemmy growled: “If you want to hang around till tonight, I’ll be in the pub down by the canal this evening.”

Unable to believe our luck, we kicked our heels around Ladbroke Grove until Lemmy strolled through the pub door at the appointed time. We pooled our money to buy him a drink, and stood around starstruck, watching as he emptied the fruit machine, not really knowing what to say. That didn’t matter. The point was that he’d been true to his word. But then honesty has always been his watchword. You take him as you find him, or you don’t take him at all. So when Lemmy says he has no intention of retiring, you have to believe him.

I just can’t picture you on the beach, jeans rolled up, eating an ice-cream. But isn’t there something to be said for a quieter life?

Maybe next year I’ll start doing a bit less. But the thing is, I don’t like to admit defeat, you know? When we first started, people gave this band six months, and here we are forty years later. So… suck that, you know? I won’t admit defeat for any reason. If I want to do something, and I still believe that I’m able, then I’ll fucking do it. I like to prove people wrong.

So to get back out and complete the show in St Louis must have felt wonderful?

Yeah, of course. There was a sense of, “Thank fuck for that.” It’s bad to let people down. I hate it when… [pauses] it all becomes your fault, you know? Although there’s nothing I can do about it.

If you had to rate those recent shows…

[Interrupting] Honestly, they weren’t that bad. It’s not all that doomy. We had some really good shows on that American tour.

So can we be categorical: nobody’s holding the proverbial gun to your head and saying you have to keep on touring?

No, no. There’s no pressure. And I’m keeping on doing what I do. Todd [Singerman, Motörhead’s manager] says that if at any time I want to stop, I should just tell him. But no, I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to say that – ever. I just want to keep going and see what happens. Beyond that, I can’t tell you.

So when people suggest – for the best possible reasons – that these fortieth anniversary UK shows really should be a farewell tour, you take the opposite view?

I do, yeah. I don’t see why we should be strangled by that [the situation]. We’ve just put out two of the best albums we’ve ever done, you know? To me it’s quite obvious that we’re not done yet.

As you quite rightly say, Motörhead still make superb records; to the point that people no longer obsess over the three-piece line-up from the 1980s; No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith and the rest. But while the mind is willing, the body is becoming ever less reliable. Can you try to verbalise that sense of frustration?

How old are you now, Dave?

I’m fifty-two.

Yeah [chuckles]. So you’re still alright. It’s when you get to sixty when everything starts to go pear-shaped. Everyone thinks that becoming an older guy is easy, but you never consider it fully. It comes as quite a shock. But the thing is, I don’t want to give in to it.

Barring any further misfortune, by the time you read this, Motörhead’s 40th anniversary tour of Europe will be under way. Between the middle of November and the middle of next February the band are scheduled to play 33 dates in 14 countries. Even allowing for rest days and a Christmas break – and despite Lemmy’s denials – it’s a gruelling itinerary for a man about to enter his eighth decade. But the old warhorse clearly won’t have it any other way.

In some way his defiance is understandable. The current Motörhead line-up (the band slimmed down to a three-piece after the acrimonious departure of guitarist Würzel in 1995) marked their 20th anniversary this year. Starting with 2005’s Inferno there have been a series of high-quality albums – something you don’t get from many other bands of their vintage. The Motörhead merchandising empire has expanded to take in everything from a branded Scotch (“Life is less painful with Motörhead whisky,” Lemmy proclaims in the adverts) and the specially brewed Bastards lager (named after their 1993 album), to Motörheadphones and even their own range of sex toys, which includes the Ace Of Spades power vibrator.

The fact is that Motörhead – and Lemmy in particular – are now more famous than they’ve been since No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith slammed to the top of the UK album chart back in 1981. If it weren’t for Lemmy’s health issues, you could say they were in the rudest of health.

After your gig at London’s Hyde Park last summer, which was upsetting for a lot of fans, it seemed like it might have marked the end of Motörhead. You’d seemed so awfully frail.

No, that one wasn’t one of our best gigs. But like I already said, I have good days and bad days. I’d like to have had a better day on that one. And the funny thing is, whenever you’re having a bad day and you try to make it better, that only ever makes it worse [laughs].

Do you still intend to release a follow-up to Bad Magic within two years?

In fact it might be a bit sooner than that.

It must be a lot easier to make records than to play live?

Not particularly. They’re both very different. In some ways it’s easier and others much harder. If you’re in the studio and can’t think of anything, that’s incredibly frustrating. I did have some writer’s block on this one, and that lasted for about two weeks. And then it all came flooding out. It’s funny, though I wasn’t laughing, but creativity is not something you can turn off and on like a tap.

When you spoke to Classic Rock in 2013 you seemed to think the band would continue to record, but possibly cease touring in the not too distant future.

Yeah, I did say that. And it might happen, but obviously I hope not. I like it too much on stage, you know?

It goes without saying that you’ve earned the right to keep on trying. But is it fair to expect the audience to turn up and then maybe go home early when a show is stopped, or for them to leave disappointed when the band doesn’t play to its usual standards?

No, of course it isn’t. That’s why I hate cutting a gig short or cancelling. I really fucking hate that. As a gig-goer myself I remember what that was like. Even with a shortened show it’s still good to see the band, but you are left feeling a bit cheated. People work hard to pay for tickets. Audiences always seem to blame the band, when it’s not always their fault. It’s getting a bit doomy, this interview, Dave, isn’t it?

His voice has become so quiet and subdued that I mistakenly think he has said something about the Doobie Brothers. “No, no,” he says, puzzled. “Doomy.”

It’s almost time to finish. We’ve been talking for just 15 minutes, but it’s clear that he’s laid his cards out on the table and the message is clear: he and the rest of Motörhead will continue to put on the best shows they possibly can. Those who are willing to see them try are welcome to come along; those who consider it too much of a risk… well, Lemmy won’t say it in as many words, but he probably wouldn’t blame you.

He’s joked in the past about “doing a Tommy Cooper” and dying on stage, bass guitar in hand. Or maybe he wasn’t joking. Lemmy is the sort of man who has considered all future possibilities, even going so far as to suggest that if that day came, it shouldn’t necessarily spell the end for the rock’n’roll institution he created 40 years ago. “If the other two decided that they wanted to carry on as Motörhead, I wouldn’t have a problem with that,” Lemmy told Classic Rock. “Phil [Taylor, drummer] and Eddie [Clarke, guitarist] left and we carried on without them. It was a bit of a wrench, but nobody’s irreplaceable.”

It’s all getting a little doomy again, so we talk about his plans for his 70th birthday (“I’ll do the thing that I usually do. I’ll go off to Vegas for a bit”) and Motörhead’s UK shows in January, where they’ll be supported by old mates Saxon and Girlschool.

“It’s a good bill,” he says. “It’s the third time we’ll have done it and it really seems to work. We’ve had faith in our fans for a long time and they’ve had faith in us for just as long. There’s no reason that should change… yet. And believe me, if I start to feel like I’m cheating the fans, then I’ll stop.”

So I’ll see you at Hammersmith then. I’m looking forward to that.

It’ll be nice to see you, too. Cheer up, you bastard [laughs].

It sounds like you’re in a fairly good head space, despite everything. Do you still get out of bed in the morning and smile?

Sometimes I’m not even in bed in the morning. Nothing’s changed that much.

Motörhead’s UK tour begins on January 23.

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.