2017: A year in the life of Brian May

"Just out of this world" – that’s how his life in Queen is summed up by Brian May – or rather, Doctor Brian May, CBE, for whom 2017 has been another memorable year in a career of many

In July 18, 2017, when Queen + Adam Lambert played at the Air Canada Centre in Toronto, 20,000 people sang Happy Birthday to one of the band, who would be turning 70 just a few hours after the show ended: Brian May. Reaching such a landmark was a rather strange experience for Queen’s guitarist – now Dr Brian May, CBE, let us not forget. “I can’t really believe that I’m that age,” he says. “It’s really odd.”

It has been a busy year for the doc. The Queen + Adam Lambert tour ran through North America and Europe, heading into the UK at the end of November. A 40th-anniversary box-set reissue of Queen’s classic album News Of The World was released. And there was May’s book Queen In 3-D, featuring hundreds of previously unpublished photographs that he shot on vintage stereoscopic cameras throughout his career with the band, plus his written account of Queen’s history – as close as he has come to writing a full autobiography.

Twenty-six years since the death of Queen singer Freddie Mercury, and 20 years since bassist John Deacon retired from the music industry, May and drummer Roger Taylor are not yet ready to let go of the band they co-founded back in 1970. “I don’t want to retire,” says May, adding with a wry smile: “I’m just thankful that I got to this point.”

May talks to Classic Rock about the past, present and future of Queen, the long-awaited Freddie Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody, Axl Rose, Elton John, and why it would be nice if people called him ‘Doctor’.

For many Queen fans it’s taken a while, but do you feel that Adam Lambert has now really proven himself as the singer for the band?

He has. Adam is amazing, he really is. I constantly wonder where that came from. How did the universe manage to make that happen?

Could you see Queen making a new studio album with Adam?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

I don’t know. We enjoy interpreting the canon, the oeuvre, and that’s as far as we’ve got.

Has this latest tour been fun, hard work, a bit of both?

It’s still hard pressing the button to be away from home for two months at a time, more than a couple of times a year. But it’s worth it because something great happens. There’s magic, and you see joy in people’s faces. It’s what it always was. Somehow it’s all worth it.

As the old song goes…

Apparently it was. And it is!

Is the Freddie biopic finished now?

We’re finally seeing it coming to fruition, although I can’t say too much about it. Eight years we’ve been working on getting it off the ground. Roger and I – to some extent against our will – have hung in there for all this time. But finally we’ve arrived at a place where we have the right director and the right script and we feel good about it. We’re very conscious that we get one shot, and if we don’t do it, someone else will do it badly. We will do it without avoiding anything – any aspect of Freddie. But we will try to keep it all in balance. I think if we get it right it will crystallize the way the world understands Freddie.

How should he be remembered?

I think in Freddie’s mind he was a musician and a creator first. So that’s a perspective we want to keep. He was a family member second, with us as a group. It was a very strong thing, and we’d like that to be represented. And the whole thing about his sexuality and his flamboyance, if you want to call it that, and all the things that made him tick, they are also vitally important as well, and none of them can be ducked or smoothed over. We don’t want to present him as some kind of unreal person. He had, like the rest of us, his great bits and his not so great bits. And in a sense there’s a kind of superhero quality to him. I think if we get it right, people will appreciate all over again what a great bit of machinery Freddie was.

Writing in Queen In 3-D, you describe Freddie as being insecure.

He really was. He built this armour around himself. It’s true of so many performers. And that’s how Freddie was able to metamorphose into the performer that you saw on stage. He started off as someone very insecure but with massive dreams, and he made himself what he became.

You also talked about the creative tension between the members of the band – a sense of rivalry as competing songwriters.

I find that’s true of life in general, not just for a group making albums. That feeling of being roped out of a situation is a powerful and dangerous thing. And I think it was true between all four us. There were areas that we didn’t invade…

Meaning what?

Everybody writes songs about what is around them, but unconsciously the songs are always about what is inside them as well. I think that’s universally true.

When Freddie delivered Bohemian Rhapsody – now seen as his masterpiece – to the band, what input did he allow you to have?

A lot of the time, with a song that came from Freddie the backing track would be piano, bass and drums, and that’s your skeleton. They would be putting that down, and I would be on the control room listening and making comments. And I asked Freddie to have that spot for my solo – I wanted to have that verse spot and I would kind of sing it on the guitar the way I heard it.

When did you work best as a team?

I remember sitting down with Freddie in the Munich days and speaking about It’s A Hard Life, and hammering out every word of every line together, because we were actually talking about what this song meant. And I think also Freddie and John [Deacon] had moments of getting close to the inner meaning of a song. Freddie and John worked on Another One Bites The Dust very closely. John wasn’t a person who could sing, so John would speak it to Freddie and Freddie would start to sing it, and I think during that process they would unravel what is this thing that we’re doing?

Near the end of Freddie’s life, when the band made the Innuendo album, did he need you more than ever?

Well, I remember Freddie and I sat for a long time working on the lyrics for The Show Must Go On. He was quite ill at that point, but he sat with me for a few hours working on a couple of lines. As far as the story of the song went, we were working on it together. But perhaps there was still a level of meaning beyond which we didn’t look. He wasn’t well – he disappeared and I didn’t see him for quite a while – so I finished off the song using those bricks that we built together, the cornerstones.

In your book Queen In 3-D you recall a moment from 1977 when the band headlined at New York’s Madison Square Garden for the first time, performing at such a high level that you felt as if you were levitating.

It was incredible. I’ll never forget that feeling. It actually felt like our feet were not quite touching the stage. It was an amazing experience. It really did feel like that. It’s not an exaggeration. I’m not being poetical.

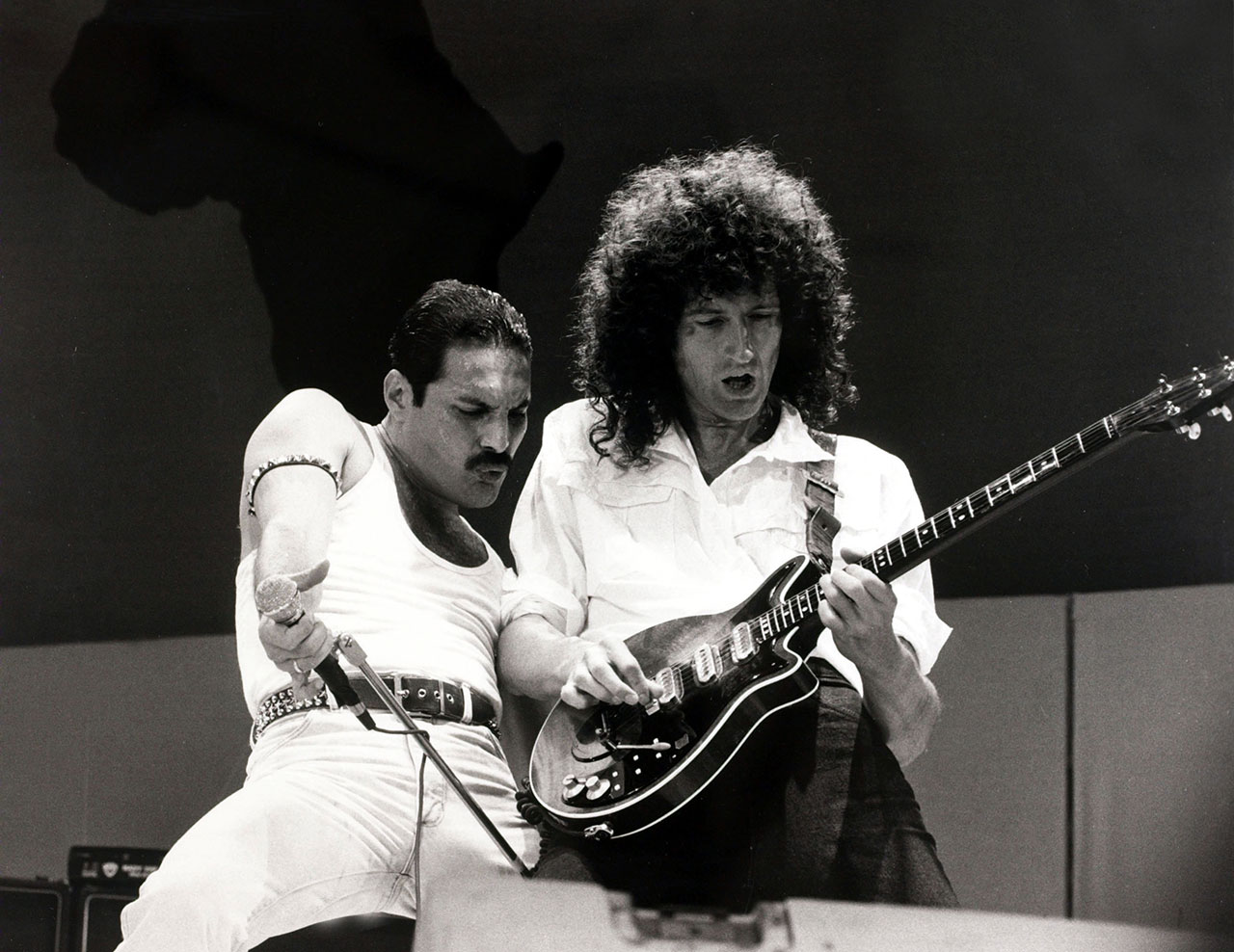

In some ways, though, surely Queen never played a better show than the one at Live Aid in 1985?

Oh, it was really a great moment for us. We were used to playing stadia in South America, full of people who had all bought tickets that say ‘Queen’ on them. For Live Aid they’d all bought tickets for whoever was announced in the beginning, not us, and by the time we were added to the bill it was sold out. So that was in the back of our minds. What is this going to be like? Are they going to react? Are they going to relate? We had no idea. But as soon as we hit the stage it felt like it was our audience. That was the most amazing thing. It felt like everyone was a million per cent with us.

And for that show Freddie delivered the performance of a lifetime.

He was able to involve everybody, right to the back of that stadium. You could feel it. And you can see it in the video. I’m not sure we realised that this would happen, and that was extraordinary to watch, and extraordinary because it was an unusual talent to have in those days. Back then there weren’t stadium bands, and most of the acts on that bill had never played in a situation like that. So really, Freddie had skills beyond the norm. We did as a band as well, but particularly Freddie.

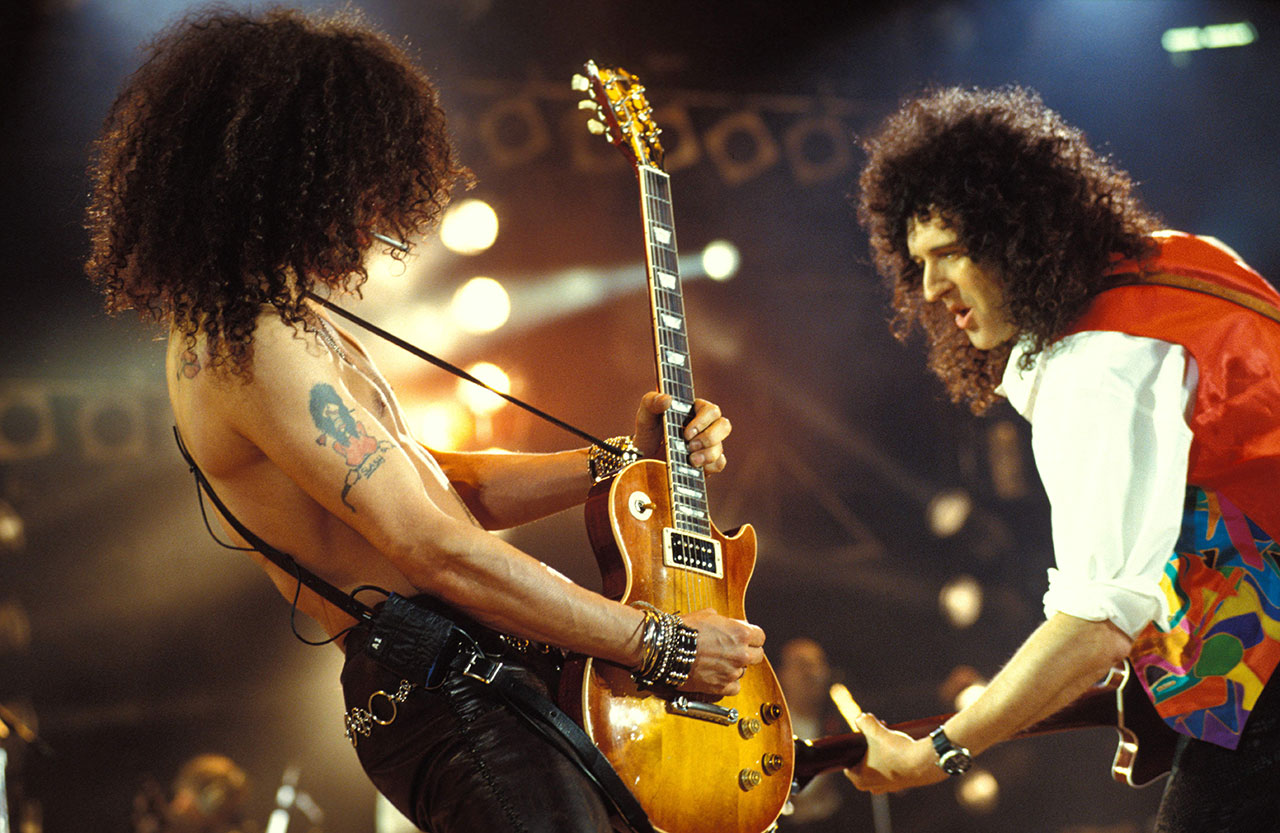

It was at Wembley Stadium, the scene of Live Aid, that the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert For AIDS Awareness was held on April 20, 1992, a little over a year after Freddie’s death. Queen performed with a cast of singers, including David Bowie and Robert Plant. And on Bohemian Rhapsody there was a duet between Elton John and Axl Rose…

It was a magnificent coming together. And I’ll never forget Axl’s entrance in Bohemian Rhapsody, coming on like this whirling dervish. He was pure energy, Axl, and it was just what was needed, just what we’d hoped for, and more besides. The guys in Guns N’ Roses are great. Slash is just a wonderful person. I’m happy to communicate with him, and we do on animal issues as well as musical issues. So there you have one of the world’s great souls. And I’m thrilled that Axl and Slash got back together. I think that’s what the world wanted.

Looking back on your life, what are you most proud of?

With music, the fulfillment is in knowing that it’s done to the best of your ability, it’s fulfilled a dream and it’s become what you dreamed it could be. It’s the creation of those things, and you know that no one else has done it, and nobody else could have done it quite in the way you’ve done it.

Is your PhD in astrophysics one of your greatest achievements?

It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. That’s why people want to be called ‘doctor’ when they’ve got a PhD, because it didn’t come easy.

Should I have called you ‘doctor’?

No, you’re fine [laughs]. But being called ‘doctor’, it’s like badge you wear because you’ve been through such shit, such a challenge to your self-belief that you came through.

How would you sum up your life in Queen?

It has been unforgettable and unique and unrepeatable. Just out of this world.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”