Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour is back with a new solo album and six-night residency at London's Royal Albert Hall, and it's probably fair to say that we've been here before. In 2016 he released Rattle That Lock, and played half a dozen shows at the same venue at the end of a tour to promote the album. As it was released, we boarded Gilmour's houseboat on the River Thames, where he told us about his 50 years with Pink Floyd.

Tucked away on the river bank in Hampton is an exotic houseboat called The Astoria. Charlie Chaplin spent a night on board in 1921, and remembered it as “rather an elaborate affair with mahogany panelling and staterooms for the guests. It was lit up with festoons of coloured lights.”

In 1986 its upper-crust owner was approached by three stubbly individuals wearing T-shirts and was surprised – though delighted – when “one of these yobbos offered to buy it for cash”. At which point the next stage of this sumptuous craft’s life began with the installation of a recording studio.

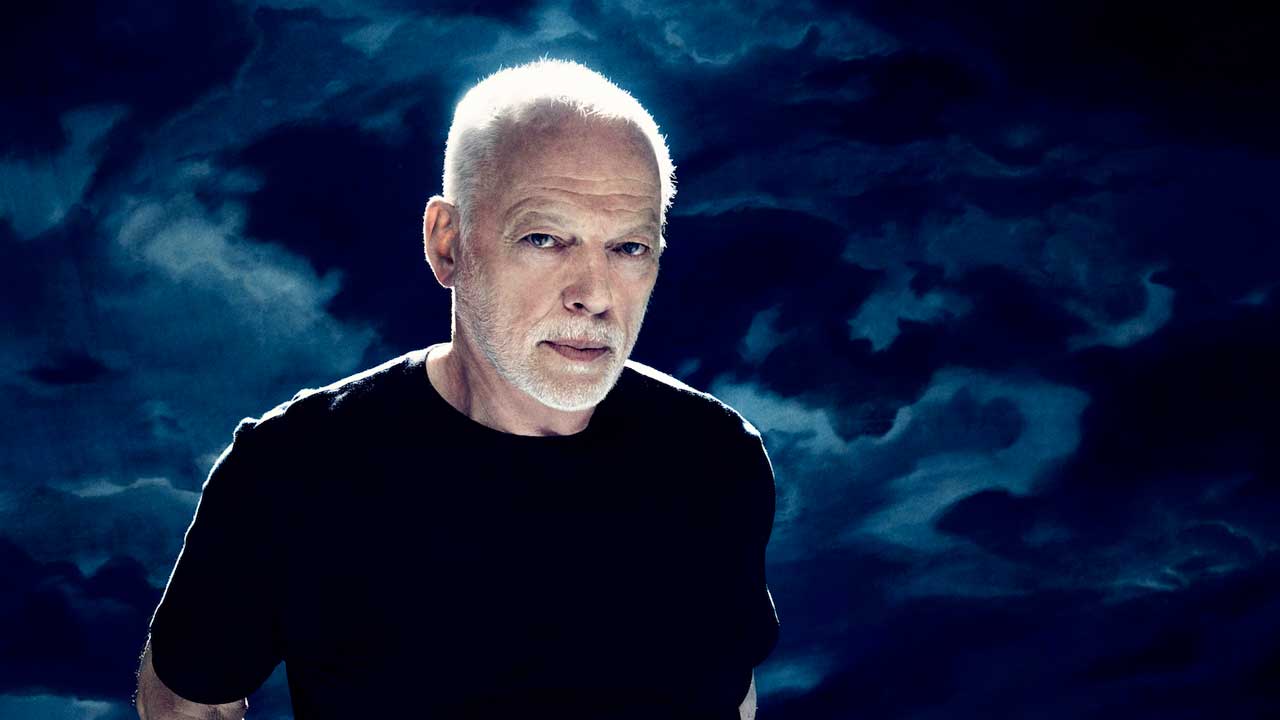

There are many words you might attach to The Astoria’s current proprietor, but ‘yobbo’ is most certainly not one of them. David Gilmour has a poise and elegance about him, dressed from head to toe in black, a sense of grandeur, an appreciation of the finer things in life. His conversation, much like his music, is unhurried and thoughtful. At one moment he points out of the window – “Look at that, that’s a smart bit of kit!” – as the gleaming, gold-painted Royal Barge glides past on its way to Hampton Court.

Last November came the release of Pink Floyd’s much-anticipated The Endless River. A series of soundscapes edited from out-takes from their 1994 album The Division Bell, it was, we were told, the final outing from Floyd.

David Gilmour has since finished Rattle That Lock, his sublime and hugely varied fourth solo album, and ushers me into The Astoria’s tiny front studio to discuss it – along with the legacy of what he now rather touchingly calls “our pop group”.

I recognise this room. Isn’t there a picture of you, Nick Mason and Rick Wright recording here in the booklet for The Endless River?

There is. We made pretty much the whole of A Momentary Lapse Of Reason and The Division Bell in this room. Which works, as you often stick an amp in another room anyway to get the separation from the drums.

The view of the river from the windows – in fact having windows at all – seems to fit with the ambient sound of your music.

Well I’ve never been keen on the traditional cellar that most studios are – no windows, no natural light, those days when you worked all hours and didn’t want the dawn light creeping in and disturbing your reveries. But [adopts creaky voice] in our old age we now like to stick to office hours.

There are so many different types of music on your new album, Rattle That Lock: a lot of the Pink Floyd signature sound, but also a waltz, some funk and two jazz songs. Is it liberating to be able to have that kind of variety?

I don’t know if it’s liberating. I honestly don’t know how it happens, actually. Whatever arrives, we just go with it. I don’t have a plan. We work on it until it starts making sense, and then we cut a few things out and concentrate on what we’ve got going for us.

And you listen to things like The Girl In The Yellow Dress, that sort of jazzy one, and you think: “Does this fit?” And then you think: “Who gives a fuck? It’s great. It’ll fit!” I think I’m quite lucky that – like ’em or not – my voice and my guitar playing are distinctive. They’re me and recognisably so, and that ties everything together.

How do you arrive at a song like The Girl In The Yellow Dress? Do you just wake up in the morning with a head full of forties jazz?

These things just arrive and I don’t know where or how. A couple of chords come and you start going down an alley – [beckons] “Come this way!” – and you follow them. Robert Wyatt plays the cornet on that one, recorded quite a few years ago.

The waltz track, Faces Of Stone, has echoes of Leonard Cohen, and it’s about the passage of time into old age. Is it fact, or fiction?

That one is about my mother’s last years and the nine-month crossover between my last child being born and my mother dying – they were on the planet together for nine months. She had a sort of dementia, and the waltz thing lends itself to a bit of madness, a clarinet waffling away, an accordion and a calliope [pump organ] to create a bit of atmosphere – that boom-tang-tang boom-tang-tang sound. I had a very difficult relationship with my mother, and it’s just nice to… [trails off].

In what way difficult?

Well… it’s difficult to explain. There’s stuff in there about her getting a place at RADA [the Royal Academy Of Dramatic Art] when she was a teenager and her family not being able to afford to take it up. She was from Blackpool. Moving to London and going to RADA was her dream. So she was disappointed and unfulfilled and she… lived that fulfillment through me a bit, which created all manner of tensions. But [shrugs] life is complicated.

It’s based on a particular day when we were walking in a park in London and she was having hallucinations and seeing things that weren’t there, and I was thinking: “Hmmm, interesting,” the beginnings of dementia. And later that day she did actually hold my new-born daughter in her arms. So you take a little idea like that and try and paint a picture.

A lot of lyrics for your music are written by your wife, Polly Samson. How does that work?

What happens is I play her a musical track – or rather, a number of tracks – and if she expresses an interest in one I’ll put it on her iPod and she’ll listen to it when she’s walking. It has to be something she likes, she has to be inspired. There are two songs written by me on this album, and even those had some assistance from my talented wife. She tried very hard for years and years to see inside my mind, and look out from my eyes and write from that standpoint, and now she’s realised that’s not really necessary; if they come out of her but I sing them with enough conviction, they’re still going to sound like they’re connected to me.

The title track, Rattle That Lock, is built around the French travel-announcement jingle, like an echo of Kraftwerk’s hymns to the joys of European trains. Where did the idea for that come from?

When you go to St Pancras station or airports, the jingles they play before announcements are usually really tacky and boring. But I heard this SNCF jingle in France, and it really bounces out. It’s got a little melody, it’s got a rhythm, it’s got a little syncopation, and it makes you want to jig a little bit. So I recorded it on my iPhone – this was in Aix-en-Provence – and brought it home and started working on it.

The whole record has a shape to it – we tried to make it in the arc of a single day ending with the crackling camp-fire. The day starts at five a.m. – which is the title of the first track – and there’s some birdsong and dog barking, and Canada geese, which I recorded at about five in the morning out of my window. And then it goes on through the things you do or the thoughts you might have. The kind of day when you could have gone to a nightclub and seen this jazz band, and you sit by a fire and cook some sausages while an owl hoots in the background before you crawl off, half-pissed, to your cot. It’s not very literal or specific or linear, it’s trying to make it have a flow.

Was it hard writing the song about Rick Wright [A Boat Lies Waiting]? At some stage the two of you must have been very close.

Rick and I go back… I mean, I was twenty-one when I joined our pop group. We didn’t spend our time being close, but we had a musical telepathy and, at its best, we knew exactly what the other was going to do and could bounce off each other. Rick had his moments of being rather down about various things, and towards what was the end of his life – none of us knew that at the time – he came on board to do my On An Island tour and had the time of his life.

In what way?

We’d get to a certain moment in the set where I was introducing people, and Polly would shout [French accent] “Reee-shard! Reee-shard!” And then people in the audience who’d been there the night before noticed and started shouting it too, and it grew and grew every show, and he visibly puffed up with joy! I really think that helped boost his confidence and he started playing more effusively. We just felt he should be fêted a little, as he was so retiring and tended to be in the background, and I’m up the front there and I’m, you know, big and strong. So he had the time of his life and really loved it and was playing brilliantly. And I’d have loved to have had him around to help make this record [he died in 2008].

I interviewed Nick Mason and Roger Waters recently and asked about the likelihood of Floyd reunion. Nick said: “I love touring and I live in hope”. Roger said it was “out of the question”, as life at his age [71] “should be devoted to doing the things you want to do”. Pink Floyd so far is three-act play. Will there ever be a fourth act?

No. I’m done with it. I’ve had a life in Pink Floyd for – what’s twenty-one from sixty-nine? Quite a lot of years. I’ve had forty-eight years in Pink Floyd – quite a few of those years at the beginning, with Roger – and those years in what is now considered to be our heyday were ninety-five per cent musically fulfilling and joyous and full of fun and laughter. And I certainly don’t want to let the other five per cent colour my view of what was a long and fantastic time together. But it has run its course, we are done, and it would be fakery to go back and do it again.

And to do it without Rick would just be wrong. I’m all for Roger doing whatever he wants to do and enjoying himself and getting the joy he must have had out of those Wall shows. I’m at peace with all of these things. But I absolutely don’t want to go back. I don’t want to go and play stadiums… under the [group] banner. I’m free to do exactly what I want to do and how I want to do it. I don’t know if it’s as good as Pink Floyd or worse than Pink Floyd or better than Pink Floyd. I don’t give a shit. It’s what I want to do and it’s what I will do.

Give me an example of a Pink Floyd moment you re-run in your head over and over again because it was magnificent.

Oh, the great moments are legion. I have thousands of snapshot memories that are great. Meddle was a great moment for us. It showed the way forth and it was successful. But then so was A Saucerful Of Secrets. Dark Side Of The Moon obviously was the breakthrough moment and was terrific, and we suddenly moved up from the medium-time to the mega-time.

How about a moment when you curl up under the duvet, thinking about the horror of it all?

I don’t have any that embarrassing, though if I watch Live At Pompeii, I cringe.

It’s brilliant. And at least two of you don’t have a shirt on!

Exactly! It’s just… it’s just personal. Mostly I can see how great it all is, and it’s all sitting there in its memory box mostly happily. I’m very good at forgetting all the bad shit anyway.

When you watch those old bits of footage of the early Floyd do you recognise the person you were back then?

[Peers at an imaginary screen] I do see a chap there! In those days the music was exploratory and it was exciting to explore. But that, to me now, looks like a process – a process to find out what you do and don’t like. And when you get older – necessarily, it seems to me – you find what you do like, and that maybe narrows your vision down a little bit. And in those early days, while it was exciting, there was an awful lot of it that was embarrassing and you go: “Oh, God, what are we going to do now?”

How do you mean?

Well we would have a template of what we were playing live. Someone would count in or start playing, and you’d know what the title was, and you’d have a rough template and then you’d just fly off on any tack you liked, and the music would build up and fly away and wander off in another direction, and some of those directions were dead-ends and some were exciting.

What do you remember of the brief period when you and Syd were in the group at the same time?

It was tragic, really. There were five gigs we did together and he would [sighs]… We’ve got a bit of film of Syd in a dressing room somewhere at one of those gigs, and he dances this little jig, a little dance, and he’s all smiling and laughing. But you just look at him and go: “Oh God, no, tragic.” Poor chap. I can’t remember much about it. I was brand new and I think they knew I’d be taking it over.

Was there one song that you never got tired of playing?

For the very palpable joy that things like Comfortably Numb and Wish You Were Here give to an audience, I never tire of them as I know what they’re doing. I suppose playing that same old thing again can be seen as being tedious, but really I’m always happy to do the ones people love.

I remember the big wooden aeroplane that ran down a wire over the audiences heads into the stage at Knebworth in 1975 during Dark Side Of The Moon. Does that funny old analogue world seem rather quaint now in the 21st century?

It is funny, it is quaint. And all those things you could do so much better today, but would they be any more effective? I don’t know. Today that could happen like magic but everyone would think: “Oh yeah? I saw that in Star Wars III”. But back then it was really real and shocking and people went: “Fucking hell! An aeroplane flying over our heads!” Everything now has to get bigger and better and better is bigger and not better.

What are your memories of Live 8?

I thoroughly enjoyed it, though we had a few days of very tense rehearsals. We hadn’t spoken to each other for years.

How did you decide what to play?

We made suggestions and Roger made suggestions, and I didn’t care for Roger’s suggestions. In the end I thought, actually, we’re Pink Floyd and he’s our guest, and he can just do what we tell him to do or fuck off.

What did he suggest?

He wanted to do Money – which we all did actually – and Another Brick In The Wall and In The Flesh.

And he was overruled.

Basically, yes.

I was just below the stage and it looked magical to me.

It was. It was magical. We were relaxed and we enjoyed it. We did a run-through of the set the night before to no audience in the park and that was terrific, and helped us feel relaxed and confident. It went very well.

But no temptation to carry on?

Been there, done that. Obviously I accept there are people who want to go and see and hear this legend that was Pink Floyd, but I’m afraid that’s not my responsibility. To me it’s just two words that tie together the work that four people did together. It’s just a pop group. I don’t need it. I don’t need to go there. I’m not being coy or difficult, I just think that at my age I should do whatever I really want to do in life.

But I’m thrilled that each new generation that comes along seems to latch on to us, and we get a fresh bunch of followers and listeners as the years tick by. Though I don’t quite know what’s made it work for us that way when it doesn’t for quite a lot of other people.

Roger once told me that musicians who achieve the level of success you achieved “must have holes in our psyche that only adulation can fill”. Quite an honest thing to say.

It is an honest thing to say. And I think he’s right, actually. But hopefully I don’t have that hole in my psyche any longer, as I don’t see the need for that sort of adulation on that scale. Also the strange thing about stadiums is you have no way of telling if it’s going well. It’s a crowd – in the singular. You can’t really retain them as individuals. The power and energy of their ‘love’, so to speak, is a wonderful drug to boost your ego to the point where it’s overinflated.

So why would someone like the Stones carry on if it can’t be about money or critical standing? It must be about the validation of hearing 80,000 people go completely mental when you play an opening chord?

I don’t know. If anyone else in any other pop group wants to go and do that, that’s great. But I’ve forged a career that suits me pretty well. Some of these guys haven’t quite got that career forged, so I guess they feel they want to carry on doing it in that way. I’ve had reasonable commercial success and reasonable artistic satisfaction. We’ll see if this new one sells any. I suspect it’ll do quite well.

Was there one particular musician who changed the way you looked at music?

There were a number of moments that were pivotal. Bill Haley’s Rock Around The Clock was a pivotal moment for me. And that was superseded in what seemed like months by Jailhouse Rock by Elvis, also pivotal. The Beatles were pivotal. Jimi Hendrix was a pivotal moment. Pete Seeger was a pivotal moment when I was young. I learnt guitar from him. Too many to name.

Who do you listen to now?

I always listen to a new Bob, Neil or Leonard record [Dylan, Young, Cohen], but I don’t listen to much new music. When I have the radio on it all sounds dreadfully formularised to me, but I’m not its audience. When you get to sixty-nine you’re not spending every day seeking out new pop music. Obviously there are whole layers of music away from what we get on the radio and telly. It’s like that thing they say about rats: ‘You’re never more than six feet away from a rat in London’; you’re probably never more than a hundred yards from someone doing a great gig somewhere, but I’m just not aware of it. If a new Pink Floyd came along now I wouldn’t know it had happened.

So the plan now is to carry on making solo albums and occasionally tour them?

I haven’t looked that far ahead. I haven’t been out and done a tour for nine years. I’m doing five dates in Europe and then five nights in London in September/October, and I’ll see how I like it. If I like it I’ll do some more.

Have you missed it in the last nine years?

Not much.

Nick Mason misses it terribly.

He plays the drums, there’s less responsibility. I’ve had a great career. I can do it when I want to and then lay off and do all the other things that make up a life. I’ve done the relentless… everything-ing – which is what you have to do to fight your way through and create a career of the sort we had. I don’t need or want it any more. It’s fine. No regrets. Nothing – almost nothing – but great memories. I’ve done it. And I’m happy with it.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 221, published in April 2016. David Gilmour's new album Luck And Strange will be released on September 6.