Fifty years ago they were still called The Tea Set, honing their skills with Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry covers. Then bohemian art student/lead singer Syd Barrett let his imagination run wild and Pink Floyd became poster boys for 1967’s Summer of Love.

Sometimes the stars align without anyone knowing it. It’s October 1965 and Douglas January, a well-to-do Cambridge estate agent, has thrown a lavish party to mark the 21st birthdays of his twin daughters, Libby and Rosie. On the vast expanse of greenery that constitutes the back garden of his property, Trinity House in Great Shelford, January has installed a large marquee and booked some local bands as entertainment.

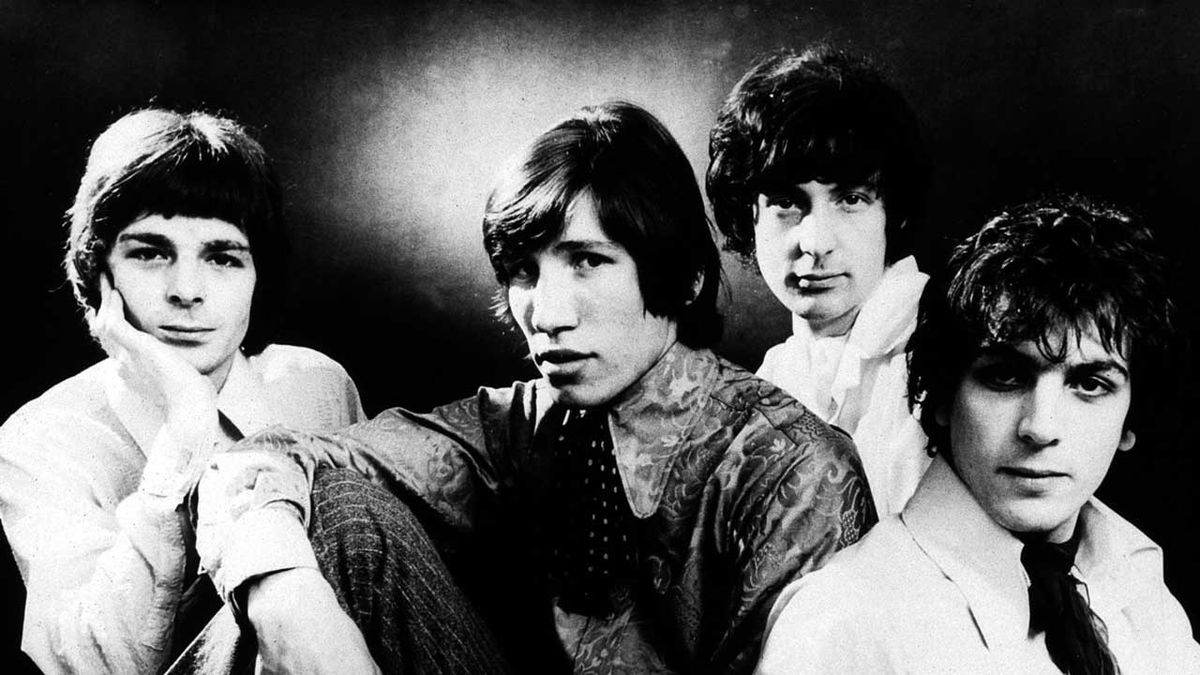

One group comprises vocalist/guitarist Syd Barrett, bass guitarist Roger Waters, keyboard player Rick Wright and drummer Nick Mason. They go by the name of The Tea Set. The other group is led by one of Syd Barrett’s childhood friends, guitarist/vocalist David Gilmour, and is called Jokers Wild.

Libby January’s boyfriend is another of Barrett and Gilmour’s friends: a film student named Storm Thorgerson who will go on to design many of Pink Floyd’s world-famous album covers. Never has the generational divide been more explicit. January Snr and his wife have invited their friends, who congregate at one end of the marquee in lounge suits and cocktail wear. At the other end, awaiting the performances by The Tea Set and Jokers Wild, are their twin daughters’ friends, decked out in dandified pre-hippie gear, drinking beer and discreetly smoking.

This crowd prefer their music loud and animated, although the first act is a visiting American folk singer named Paul Simon. No one knows who he is.

“He was a pain in the arse,” recalled Jokers Wild drummer Willie Wilson in Mark Blake’s Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story Of Pink Floyd. “He came up and said: ‘Can I play with you?’ And we were like: ‘You’re an acoustic folk singer, we’re in a rock’n’roll band.’” Jokers Wild eventually relented and let Simon join them on stage.

It all ended in a raucous fashion, with noisily received sets by Jokers Wild and The Tea Set, drunken revelry and some smashed crystal, after an overly enthusiastic Barrett attempted a magic trick with a tablecloth. While it was a memorable evening for the Januarys, it was also an historic occasion: the first musical meeting between present and future members of Pink Floyd.

However, things happened slowly. It would be another two years before David Gilmour joined Pink Floyd, and another four before Storm Thorgerson returned to Trinity House, Great Shelford, with its French windows and manicured lawn, to photograph the iconic cover for Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma.

Like most bands, Pink Floyd went through a variety of permutations before they settled on a definitive line-up. Nick Mason and Roger Waters had met at Regent Street Polytechnic in late 1962, when they were both on an architecture course. It was there they ran into fellow architecture student Rick Wright. Music served as a common bond and the trio formed their first band together, the Sigma 6, with other Poly attendees Clive Metcalfe and Keith Noble. Rehearsals in a tea room of the building’s basement involved a bunch of covers, everything from John Lee Hooker to The Searchers. They briefly played as The Abdabs and The Screaming Abdabs, before Metcalfe and Noble left to form a duo.

Both Waters and Mason became tenants at the Highgate house of tutor Mike Leonard, who spent his spare time constructing light machines. The next three years saw others lodge at Leonard’s house, including Syd Barrett, Waters’ old schoolfriend. Barrett had moved to London to study painting, his abiding passion, at Camberwell School of Art. By 1964 Mason and Waters had been joined in the group by two more Cambridge associates, guitarist Bob Klose and lead singer Chris Dennis.

Barrett, whose Cambridge upbringing was described by Mason as “possibly the most bohemian and liberal of us all”, began sitting in with them regularly. Soon Dennis was out and Barrett was in, primarily as singer-guitarist. There were pub gigs around Highgate, sometimes billed as Leonard’s Lodgers, and a show at Camberwell art school as The Spectrum Five. The band played Bo Diddley, the Rolling Stones and sundry R&B covers. One weekend hop at Regent Street Poly, in October ’64, found them supporting The Tridents with 21-year-old hotshot Jeff Beck.

A friend of Rick Wright’s secured the group some studio time in West Hampstead in February 1965. By then Barrett had started to make forays into songwriting, with the band cutting three original demos: Butterfly, Lucy Leave and Double-O Bo (“Bo Diddley meets the 007 theme,” said Mason).

But it wasn’t until The Tea Set landed a residency at the Countdown Club, a basement dive just off Kensington High Street, that they started to gel. The story goes that their first show, in February ’65, was the occasion at which Barrett rechristened the group. Taking a cue from Carolina bluesmen Pink Anderson and Floyd Council, they duly became Pink Floyd. (Confusingly, they still played shows – like Libby’s party – under The Tea Set name.)

The Countdown may have been a regular gig, but it was gruelling – and with little reward. For a fee of £15, the band played three sets per night, each lasting for 90 minutes. They swiftly hit upon a problem: not enough songs. As Nick Mason pointed out in his 2004 memoir, Inside Out: A Personal History Of Pink Floyd, this marked “the beginning of a realisation that songs could be extended with lengthy solos”. They were still unsure about what to call themselves, fluctuating between The Pink Floyd and the Tea Set, but Klose’s departure later in the year coincided with them finally settling on The Pink Floyd Sound.

Bookings were random at best. But their fortunes took a turn for the better when they secured a Sunday afternoon gig at the Marquee, deep in London’s Soho, in March 1966. With a handful of Barrett originals, and encouraged to lace their set with extended solos, the band slowly began to ditch their R&B repertoire for freakier fare. Soon they were regulars at these Sunday ‘happenings’, which became known as the Spontaneous Underground.

Peter Jenner was a Cambridge graduate with a teaching job at the LSE. More interestingly, he was also co-founder of DNA, a jazz and blues label with avant-garde leanings. Styled after New York’s ESP-Disk imprint, DNA became home to free improv groups, but Jenner was on the hunt for a slightly more conventional band. One Sunday, he headed to the Marquee.

“They were a fairly standard R&B band doing these weird improvised things in the middle,” Jenner recalls. “That’s what really got me. It was what Rick and Syd did with all the echo and things. I suppose I was very naive in some ways. They were very avant-garde and I thought I was too, and it was all going to be very beautiful, man. Let’s have another hit on the joint and all that…”

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, one of Jenner’s co-founders at DNA, was another Cambridge graduate who’d gravitated to the capital. He’d started as a photographer for Melody Maker, before quickly becoming established as one of London’s leading countercultural figures. A year earlier, in 1965, he helped set up a community action group, the London Free School.

“I first saw Pink Floyd at a Happening at the Marquee one Sunday,” he told me in 2008. “They didn’t have a light show, though there were lots of coloured lights. So it was an indicator of what was coming along. It was people making music without necessarily making singles. There was something about their improvisation; they had a fertility of imagination that was really a part of the zeitgeist.”

Both men were to play pivotal roles in the emergence of Pink Floyd as the darlings of the London underground scene. In summer ’66, the band agreed to sign to Jenner and his business partner Andrew King’s management company, Blackhill Enterprises. Hopkins then hired them for a show at All Saints Hall in Notting Hill’s Powis Gardens. There was still the odd cover, but Barrett was now unveiling experimental pieces such as Interstellar Overdrive. In satin shirts, velvet trousers and Gohill boots, they looked the part too.

The Pink Floyd Sound were the main attraction at these All Saints gigs throughout October and November ’66, attracting a diverse crowd of bohemians, students and acid heads. Mason has insisted that the band didn’t consciously set out to play “trip music”, but the psychedelic stimuli – improvised songs, echo effects, a spacey light show engulfing the stage in a miasma of bubbles and ink patterns – was impossible to ignore. “The Powis Gardens gigs marked the beginning of our popularity,” said Waters, years later.

The shows also helped fund the London Free School’s own newspaper, International Times. The Floyd played at the launch party at the Roundhouse, alongside The Soft Machine. “If you compare early Pink Floyd with Soft Machine,” offered Hopkins, “the interesting thing was that the Floyd had ‘tunes’, in inverted commas. They were both interesting bands, but I felt the Floyd had the edge. It was the momentum of what was happening at the Free School that propelled us towards starting UFO. Then the whole thing had a mind of its own.”

The UFO Club, situated in a basement on Tottenham Court Road, officially opened in December 1966. Shorthand for Underground Freak Out, owned by Hopkins and American record producer Joe Boyd, Pink Floyd were the resident band at these Friday evening ‘happenings’.

“The group and Syd’s songs were the brilliant soundtrack of the underground,” remembers Boyd. “The UFO Club eventually stood on its own feet and could break bands just by booking them. But Hoppy and Syd were equally important in giving UFO its head of steam.” Among the regulars at UFO was Jenny Fabian, author of Groupie. For her, Pink Floyd represented “the first authentic sound of acid consciousness”.

In January ’67, Joe Boyd ushered the band into Chelsea’s Sound Techniques Studios, where they spent two days recording Interstellar Overdrive, Let’s Roll Another One (aka Candy And A Currant Bun), Nick’s Boogie and Arnold Layne. The latter, Barrett’s real-life tale of a man who stole women’s underwear from washing lines, also warranted its own promo film. “Both Syd and Roger’s mums used to sometimes rent rooms to students,” explains Boyd. “Girls were neater and more reliable than boys, so both often found lingerie drying on backyard clotheslines.”

Boyd had readied a record deal with Polydor. But the sudden entrance of Bryan Morrison, who had his own booking agency and knew the top brass at EMI, resulted in a change of tack. Pink Floyd instead signed to EMI in early March, for a reported £5,000 advance. It was left to Peter Jenner to tell Boyd his services were no longer required, as EMI insisted they use an in-house producer.

Pink Floyd fully embraced their status as the latest addition to a label roster that included The Beatles. Indeed, they were only too happy to goof around for the cameras at EMI’s HQ during the signing ceremony. And with good reason. “We were genuinely excited and pretty full of ourselves,” Mason remembered later. “We had been propelled to a position that a few months before had been just a fantasy.”