66 from '66 – T-Z

The 66 records that built rock as we know it – all from 1966.

Our 66 of ‘66, from T-Z.

The 13th Floor Elevators

The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators

International Artists, November 18, 1966

Was this the first album to specifically mention the word ‘psychedelic’? Was it The Deep’s Psychedelic Moods, or Blues Magoos’ Psychedelic Lollipop?

Whatever, LSD-taking was rampant in America and the Elevators were prime disciples. Lead singer and Texan maniac Roky Erickson inspired a generation of druggy punks a decade later as this cult album, with Tommy Hall’s absurd electric jug playing driving the hit You’re Gonna Miss Me, was passed around like a furtively revered manuscript. Especially so in Liverpool where the Teardrop Explodes were avid converts. R.E.M., Primal Scream, The Jesus And Mary Chain and ZZ Top acknowledged the Elevators’ influence, Robert Plant borrowed Roky’s feral vocal style, and stoner rockers like Queens Of The Stone Age and Wooden Shjips wouldn’t be droning on without them.

The Troggs

Wild Thing

Fontana single, April 20, 1966

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Three chords, two takes and one bizarre wind instrument. That’s all it took for Andover’s Troggs to record one of the best-known rock songs of all time, and become globally recognised after just two singles.

Under the guidance of Kinks manager Larry Page – who had heard the Chip Taylor original as a demo in New York – Wild Thing was destined to be a throwaway B-side for the group, but they delivered a recording of such brilliant, neanderthal simplicity – and turned around follow-up With A Girl Like You in the same ten-minute window – that all bets were off. The establishment hated it, but the kids adored its unpolished, sexual undercurrent.

Dozens of cover versions subsequently emerged, most famously Jimi Hendrix’s incendiary performance of it at Monterey in ’67 as he smashed up his Fender Strat and set it alight. Surely Wild Thing is the ultimate garage-punk anthem and the spark for the Stooges, Ramones, White Stripes – and that bunch of long-haired louts currently pulverising guitars and bin lids somewhere in your town right now.

Ike & Tina Turner

River Deep – Mountain High

Philles single, May 1966

Soul music from the days when R&B rocked, this was an eruption of voice and music as heavy as any metal. Sheer erotic overload, no wonder Tina Turner had to remove her sweat-drenched shirt to sing in her bra after toiling through thousands of takes.

The price of this Wagnerian masterpiece, an epic expansion of The Wall Of Sound, was huge: 21 session musicians and 21 backing vocalists costing a then-unprecedented $22,000. So, too, was the toll: producer Phil Spector considered it his greatest work, and yet it turned out to be virtually his swansong, its commercial failure at least in the States – too black for the white rock demographic, too pop for soul fans – prompting a withdrawal from centre stage. The coda we know: mythic protagonist of his own psychodrama hits self-destruct button and winds up in jail. Still, this remains: what George Harrison deemed “a perfect record from start to finish”.

Various Artists

What’s Shakin

Elektra, June 1966

A collaborative effort between Elektra New York and the label’s new London office opened by Joe Boyd, this sampler/compilation included the Lovin’ Spoonful’s earliest recordings from ’65, but for British audiences the appearance of Eric Clapton And The Powerhouse was more significant. The brainchild of Manfred Mann singer Paul Jones, other participants were Steve Winwood (billed as Steve Anglo), Jack Bruce and Pete York, thus sewing the seeds for Cream and Blind Faith: The Powerhouse was the first studio-only ‘supergroup’.

While the album sold moderately, it pointed the way forward for Clapton who laid down Crossroads and Steppin’ Out (recorded and played live by Cream and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers). There was also an introduction to the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Tom Rush and Al Kooper. Elektra had gone electric and the rock sampler was born.

The Who

Substitute

Reaction single, March 1966

A Quick One

Reaction, December 9, 1966

If it wasn’t for A Quick One, The Who might have been The Action. That is to say, just another Mod band, amphetamining up American R&B until they fizzled out. But their second album was an experimental variety pack that cast lines outside of their little bullseye box – the country bounce of Don’t Look Away, the kooky circus revelry of Cobwebs And Strange, the poignant jangle of So Sad About Us and most audaciously, the nine-minute title track, a suite of six episodic songs about infidelity, sewn together with sound effects, narration and dynamic playing. Embracing the free reign that bands had in 1966, The Who chanced upon the form – the rock opera – that would make their fortune with Tommy and Quadrophenia.

Earlier in the year, the perfect single, Substitute, pushed the envelope of independence a few more inches – it was the first record that Pete Townshend produced and the first after breaking with early manager/producer Shel Talmy. It also contained the controversial line ‘I look all white but my dad was black,’ which continued the ‘f-fade away’ spirit that would be at the heart of all their best work.

The Velvet Underground

All Tomorrow’s Parties/I’ll Be Your Mirror

Verve single, July 1966

Over in New York the atmosphere couldn’t be more different from the amped-up electricity everywhere else as these monochrome artrockers presented a two-pronged observation on the company they kept – Andy Warhol and his Factory filled with artists, actors and socialites on speed. While Teutonic Ice Queen Nico struggled to provide a gentle vocal on I’ll Be Your Mirror – a pretty song that loosely addressed fandom and a search for identity, perfectly crafted by ex-bubblegum pop hack Lou Reed – on All Tomorrow’s Parties her deadpan commentary on the misfit pleasure seekers really struck home. As Mo Tucker kept minimal percussive time, John Cale hammered paper-clipped piano strings and Reed teased a one-note guitar line in ‘ostrich tuning’ (his own invention, to make a drone noise), paisley pop went goth.

Barely of cult status at the time, the Velvets’ wider legacy wouldn’t hit until the 80s, as post-Transformer generations would discover beat poetry, Ray-Bans and jangling experimentalism over and over again.

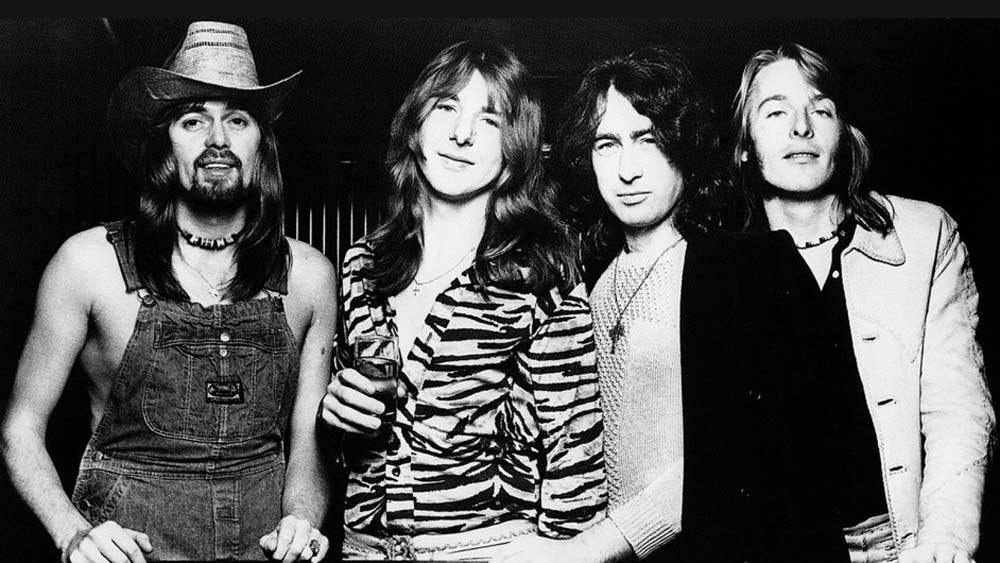

The Yardbirds

Shapes Of Things

Columbia single, March 1966

Happening Ten Years Time Ago

Columbia single, October 1966

With these two 45s, released just eight months apart, The Yardbirds defined the musical changes of ’66. February’s Shapes Of Things built on the blues with Chris Relf’s trippy multi-tracked vocal and guitarist Jeff Beck’s hammering riff and controlled feedback. It was psychedelic pop that pre-empted The Beatles’ LSD-influenced Revolver by six months.

In October The Yardbirds took their experimentation further still on one of three songs recorded with both Beck and Jimmy Page in the line-up, and here with future Led Zeppelin man John Paul Jones playing bass. Happenings Ten Years Time Ago was another head-trip pop song. Its mid-section breakdown/‘rave up’ with police-siren guitar effects now suggests a trial run for Whole Lotta Love. But what clinches it is Beck and Page’s jousting guitar riff: it’s the sound of every twin-guitar rock band in the world being invented right there on the spot.

The Young Rascals

Good Lovin’

Atlantic single, February 21, 1966

Legendary blue-eyed soul from the chart-topping Garfield, New Jersey boys, this No.1 hit was an early Arif Mardin/Tom Dowd production that featured the East Coasters in their pomp, bossing the charts from winter through summer. The absurdly infectious groove conjured by singer Felix Cavaliere, Gene Cornish, Dino Danelli and Eddie Brigati was the personification of Little Italy R&B. Here were four finger-snapping immigrant kids jumping into the melting pot with such glee that they united the States on air for months.

The song had enormous impact. Lou Reed wrote Rock & Roll with his old college friend Cavaliere in mind, and the Dead’s Bob Weir adopted it as a West Coast anthem. Remarkably underrated, the Young Rascals were the first band to cover Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone. But Good Lovin’ is the better dance tune. Ask your family doctor.

Frank Zappa

Freak Out!

Verve, June 27, 1966

Zappa recorded dozens of albums, and his genius for juxtaposing the puerile and profound, avant-garde experimentation with rock convention was there from the start. His compositional range was huge: sides one and two of this double included adroit attempts at doo wop (Go Cry On Somebody Else’s Shoulder), proto-psych (Who Are The Brain Police?), even pop (Wowie Zowie, Mother Love). Only the creepy subject matter (groupies, mind control) precluded The Mothers from mainstream success – producer Tom Wilson, who had previously worked with Simon & Garfunkel, mistook them for a straight white blues band. Instead, Zappa was destined to be the hyper-vigilant outsider, satirising straight society and the burgeoning counterculture from the sidelines. And this ambitious debut, released within a month of that other monumental double, Blonde On Blonde, was his first strike, and one of the records that gave The Beatles the impetus to create Sgt Pepper.