Sinead O’Connor used her voice, this hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck-raising falsetto, to express all of life’s emotional complexities in her songs.

Growing up in a volatile Dublin household with an abusive mother, she found catharsis in music-making, playing a guitar, gifted to her by a nun. Aged just 15, she made her recording debut with Dublin rock band In Tua Nua on a co-write Take My Hand, then worked with Ton Ton Macoute, before signing a solo deal with Ensign Records in 1985. Fanfaring her arrival proper with 1987’s astonishing The Lion And The Cobra, she appeared on the album’s sleeve with a shaved head and looked like she was screaming - she was in fact singing - and her bold, striking songs, dealing with child abuse, religion, sex and oppression, expanded chart pop’s vocabulary.

“I didn’t want to be a pop star, I wanted to be a protest singer,” she once said, and true to her word, she’d use her platform to raise awareness often at the detriment of selling records; publicly tearing up a photo of Pope John II on Saturday Night Live to protest the Catholic church’s cover up of child sexual abuse ; denouncing US war crimes and refusing to allow the US national anthem to be performed at her shows; criticising the British occupation of Northern Ireland and fighting misogyny in the record industry. Fiercely independent from day one, she produced or co-produced her albums, a creative freedom rarely afforded female artists, and her music crossed borders, spanning alt pop, jazz, reggae, world, hip hop and traditional Irish folk.

Her death, aged 56, on July 26, a year and a half after her 17-year-old son Shane took his own life, was a devastating tragedy, but her music continues to resonate. Here’s our guide to the five albums you must hear.

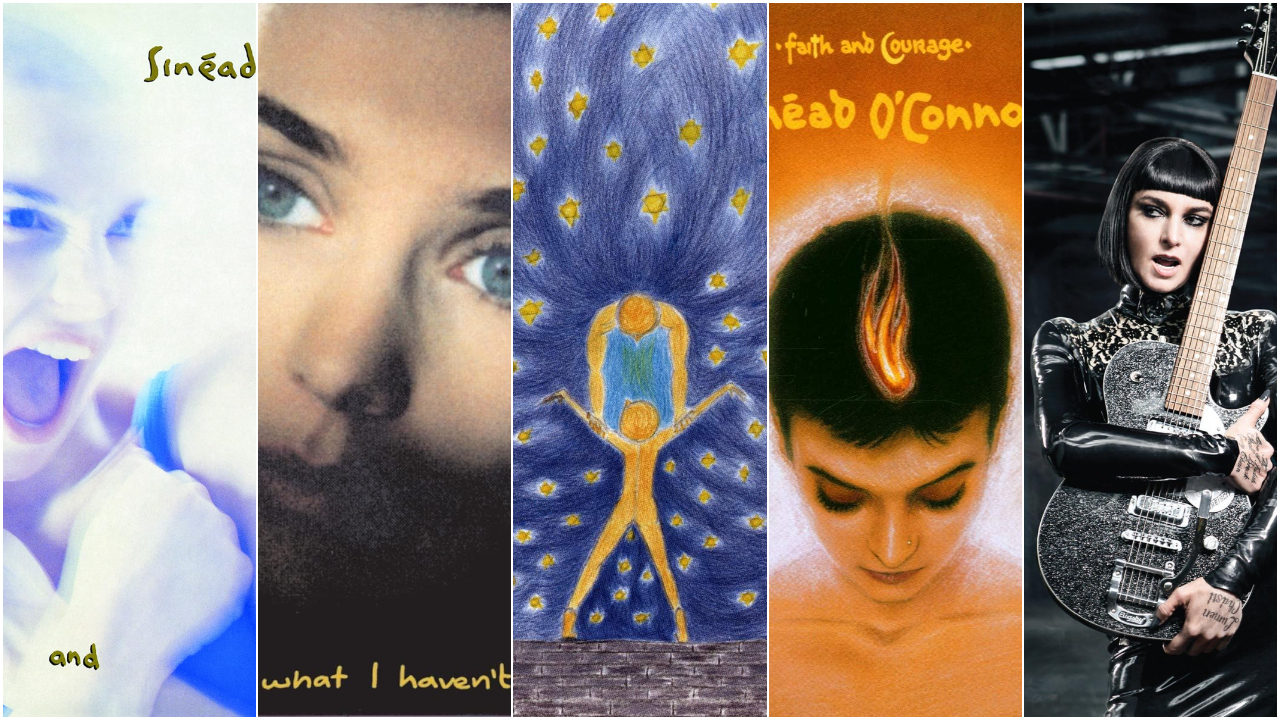

The Lion And The Cobra (1987)

O'Connor's exceptional debut album was recorded when she was just 20, and heavily pregnant - her label advised she have an abortion - and it still sounds like nothing on earth. Its nine tracks are a pain-to-catharsis primal scream taking in the compelling UK Top 20 hit, Mandinka, inspired by her reading of Alex Haley’s Roots [the Mandinka are a West African tribe] that became a student indie night staple across the UK, and Troy, an emotion-flooring outpouring of grief for her mother who was killed in a car crash when she was just 18. “I know you’re always telling me that you love me/ But just sometimes I wonder if I should believe,” she sings. A stunning introduction to an artist like no other.

I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got (1990)

Introduced by college rock anthem Jump In The River and a crushing rendition of Prince’s Nothing Compares 2 U, with its gut punch of an accompanying video, O'Connor's second album was always destined for mainstream success, and it duly reached Number 1 in the UK, Ireland, the US, Australia, Germany and half of mainland Europe. Co-produced with Nellee Hopper, it's a masterpiece which offers so much more than its most celebrated track, as borne out by the empowering Feel So Different, with her voice twisting against dramatic strings; the plaintive Black Boys On Mopeds, social commentary framed in acoustic folk, the tender, beautiful break-up lament The Last Day of Our Acquaintance, and I Am Stretched On Your Grave, her stirring recital of an anonymous Irish 17th century poem set against a loop of James Brown’s Funky Drummer break.

Universal Mother (1994)

After 1992’s Am I Not Your Girl?, an album of mostly jazz covers, O’Connor laid herself bare on her fourth album, exploring the connections between childhood trauma and motherhood on songs that are knotty and raw. Over Fire On Babylon’s enticing reggae rhythms, she opens up: “She took my father from my life/ Took my sisters and brothers”. Elsewhere her cover of Nirvana’s All Apologies sees Kurt Cobain’s grunge anthem reimagined as intimate lullaby with just her voice over strummed acoustic guitar: it’s both the most beautiful thing you’ve ever heard, and the most chilling.

Faith And Courage (2000)

O’Connor called this long awaited follow up to Universal Mother, her “survival” album, as it was written as cathartic response to her break-up with the writer John Waters, a custody battle over their daughter, and her attempted suicide in the fall out. It’s a real achievement, bold and brave and ambitious, and although there are big name producers involved - Dave Stewart, Wyclef Jean, Brian Eno, Adrian Sherwood among them - it’s Sinead who shines, defiant on the pop-noise of Daddy I’m Fine; confessional on reggae redemption number The Lamb’s Book Of Life and truly warrior like on the album’s bristling statement of intent No Man’s Woman.

I’m Not Bossy, I’m The Boss (2014)

From its title - lending support to the Ban Bossy campaign launched earlier that year - to the striking cover photo - O’Connor with black bob, wearing a black PVC catsuit and holding a guitar - to the perfectly crafted melodies and lyrics about lust, and love, and relationships, and female strength, and the music industry, her tenth and final album captures her on remarkable form. Her voice, as supple and nuanced as it was when she first started out, effortlessly jumps octaves on opener How About I Be Me - “I wanna make love like a real full woman, everyday,” she announces over R&B flavoured pop - while on James Brown, featuring Fela Kuti’s son Seun Kuti, she’s embracing new musical space, pitching herself as the Afro-funk queen. O’Connor had never sounded so self possessed.