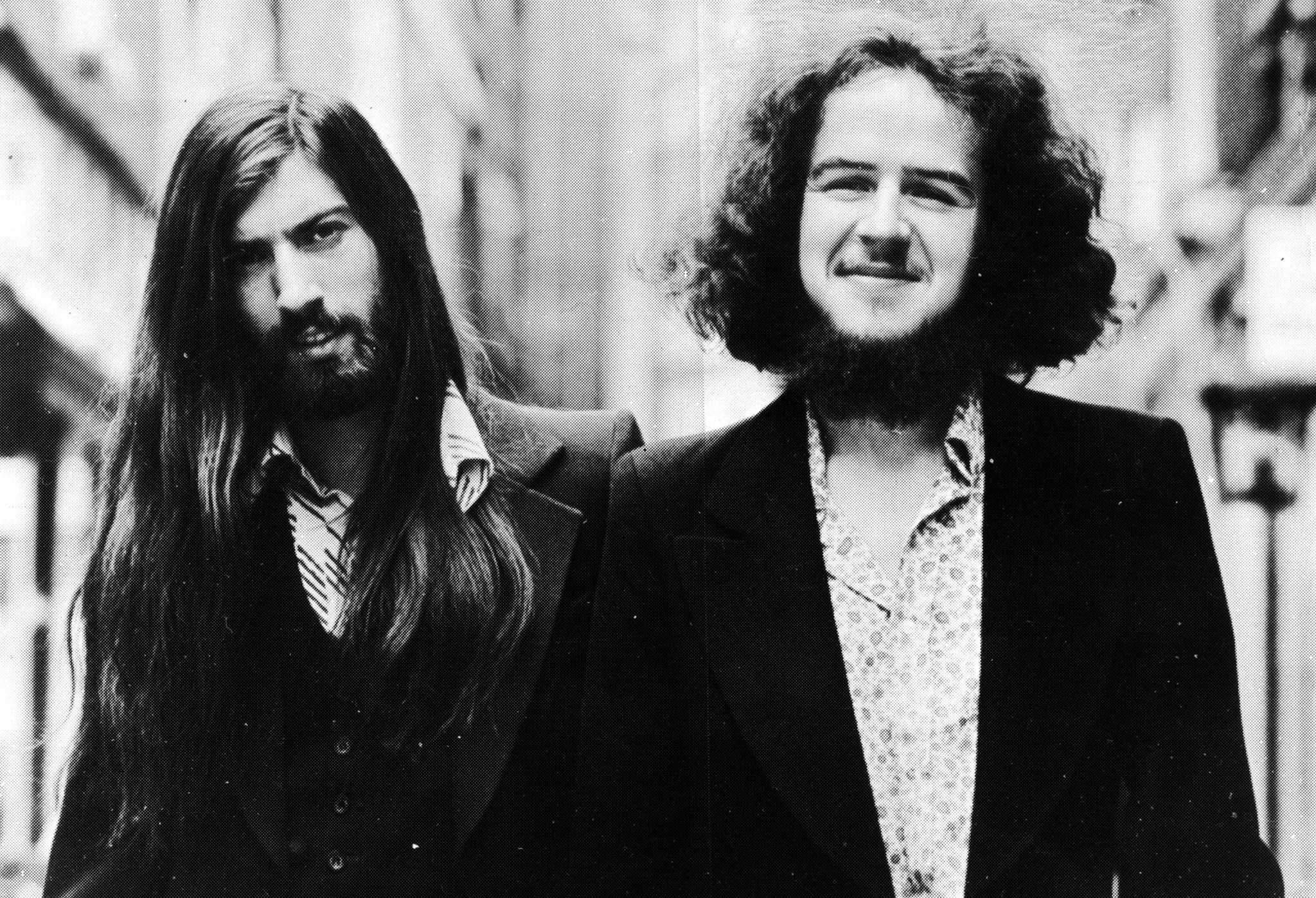

Less shouty and perhaps less underground than its peers, Chrysalis Records was a label built to last. The fact that it floated on the stock market in the late 80s and became a ‘group’ underlined the ambition, drive, vision and sincerity of the label’s founders, Chris Wright and Terry Ellis.

Like many imprints of the era, Chrysalis also had several lives, firstly as a management company representing Ten Years After and Jethro Tull, then licensing records to others, before becoming a label that had its own in-house publishing arm. It produced high-quality rock albums, some produced by Ellis himself in the early days. It championed artists as diverse as Leo Sayer and Robin Trower, before riding out new wave with the signing of Blondie and then working with Jerry Dammers on his groundbreaking 2 Tone label. Success continued in America with enormous acts such as Huey Lewis And The News and Pat Benatar.

Aside from the record label, Chrysalis’ publishing arm looked after several key, lucrative catalogues, most notably Rod Temperton’s compositions for Michael Jackson, as well as a chunk of David Bowie’s copyrights from the early 70s. Bowie’s publishing was a small consolation for the fact the label had turned him down as an artist as Ellis didn’t think much of Hunky Dory.

HOW IT BEGAN:

Chris Wright (22) and Terry Ellis (23) founded what was to become Chrysalis in a flat in London’s Shepherd’s Bush in 1967. Wright had been social secretary at Manchester University, gaining experience booking acts before going to work for the Ian Hamilton Agency. There, he represented folk singer and future newsreader Anna Ford and became the manager of a Nottingham based blues combo, Ten Years After. That year, Wright got the group a deal with Deram, where they remained until 1970, before coming to Chrysalis.

Ellis had been a university social secretary too. After leaving Newcastle University where he had booked gigs, he represented Reparata And The Delrons. Wright and Ellis then became aware of each other when they were vying to book bands at the same venues, with Ellis undercutting Wright.

It started more or less as a marriage of convenience. Originally entitled the Ellis-Wright Agency, the two decided to become a management company to represent Jethro Tull and Ten Years After. The label was formed as a result of the pair’s disgust at how MGM were handling their prime charges Tull, who had signed a one-off deal to the label.

“Chrysalis Records really came into being because Jethro Tull couldn’t get a record deal,” Wright was later to say. “MGM couldn’t even get their name right on the record.”

Titling their company punningly by combining their names after the pupa stage of a butterfly, the pair signed a licensing deal with Chris Blackwell at Island. Blackwell had promised Ellis and Wright that if they had 10 Top 20 hits, he would give them their own label. By the time they had had nine, he acquiesced.

The label took off so quickly that within a year, Chrysalis emerged as a stand-alone company. “When Chrysalis began, it was something like the group was at that stage – more or less a tentative experiment – and we all learnt together,” Tull’s Ian Anderson told Zigzag magazine in 1969.

“We tried things out,” he added, “saw how they worked, changed them around and so on, until we arrived at the stage we are now, where Chrysalis is a fairly important business force on the scene and embodies recording, management, agency, publishing, record label… the whole thing.”

Chrysalis, unlike other labels at this time, offered the whole package – management, label and publishing.

THE GOLDEN PERIOD:

Chrysalis hit the ground running and most of the 70s were a very successful time for the label. Signing Jethro Tull to Warners in the US meant the $40,000 advance paid off all their debts and made them cash rich in one fell swoop, and Tull became an enormously profitable export.

Ten Years After’s appearance at Woodstock and on the subsequent album and film guaranteed them transatlantic success, which coincided nicely with their Deram contract expiring and them signing to their management company’s label.

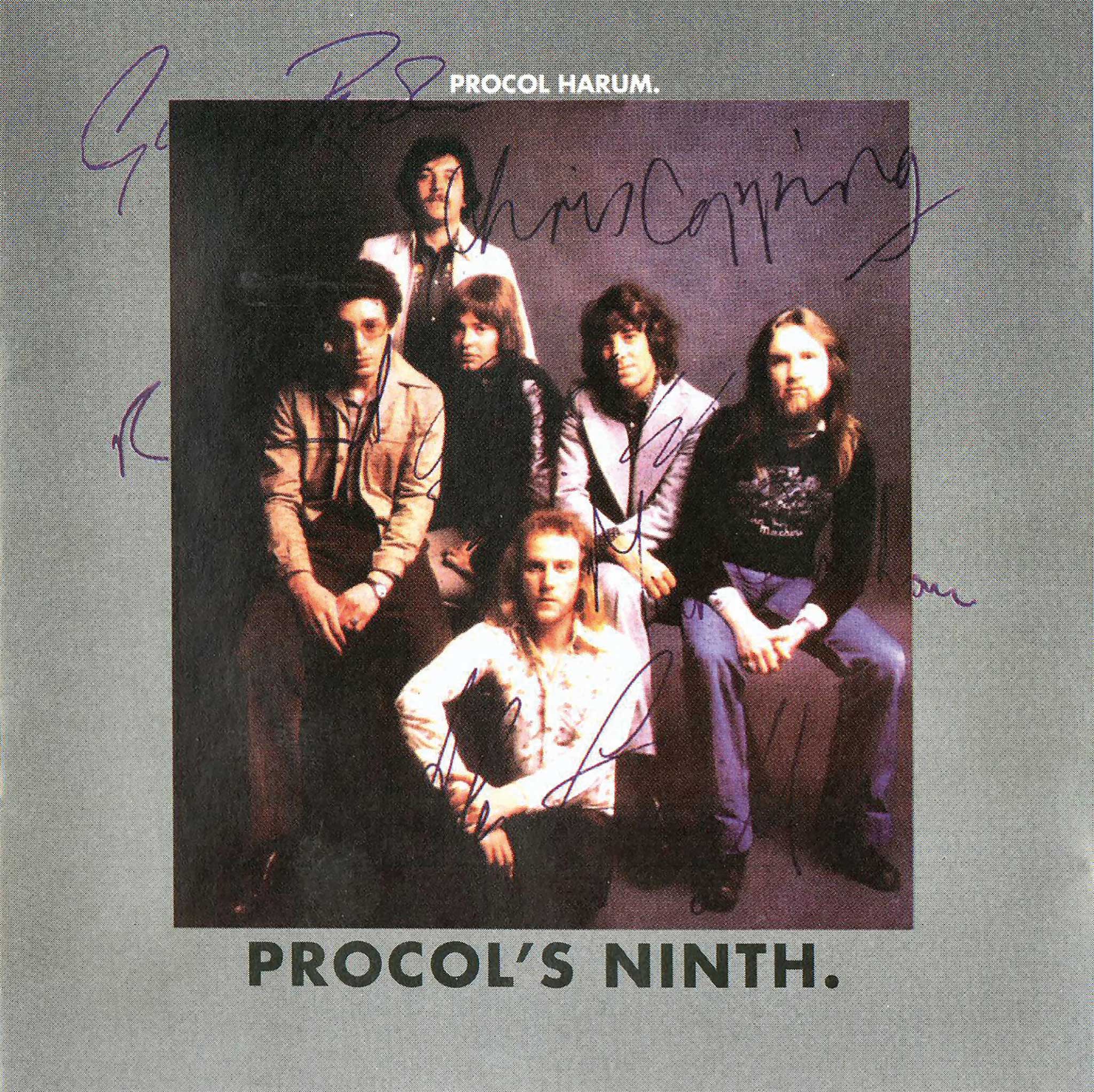

Wright favourites Procol Harum came over from Regal Zonophone in 1971. By 1974, Ellis relocated to Los Angeles to establish the US wing of the company (he went out with Karen Carpenter for a considerable period too), leaving Wright in the UK to continue developing the label’s success.

Their progressive side was maintained by the signing of Gentle Giant, who had been enjoying success in the US. “We initially met Terry on our first US tour,” Ray Shulman remembers. “We were immediately impressed with the professionalism of their operation and when things went sour with WWA, we met up with Terry. He introduced us to his partner Chris Wright, their MD Doug D’arcy and their young press man, soon to become A&R, Chris Briggs. We got on well and they were keen to sign us.

“From their point of view we were a safe bet. We already had a very loyal fan base and each record recouped its advance. From our point of view, and for similar reasons, it meant they’d leave us alone to do our thing.”

Gentle Giant made Free Hand, their most successful album to date in the US, and added to the all-round eclecticism of the label, which by now had Leo Sayer, Steeleye Span, Rory Gallagher and Frankie Miller on its books.

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT:

As punk dawned, Chrysalis was wise to it, losing out on the Pistols but quickly signing Generation X. The green butterfly label became the blue butterfly label. Jethro Tull responded by going into progressive folk and Gentle Giant went pop.

“The worst thing that happened was that our contemporaries were having hits,” Shulman recounts. “I must say the pressure to simplify our sound came from within, rather than the record company. The trouble is, as soon as we put in something overtly commercial, our inner demons would go to work and we’d musically sabotage it.”

Gentle Giant more or less relocated to America before quietly calling it a day in 1980.

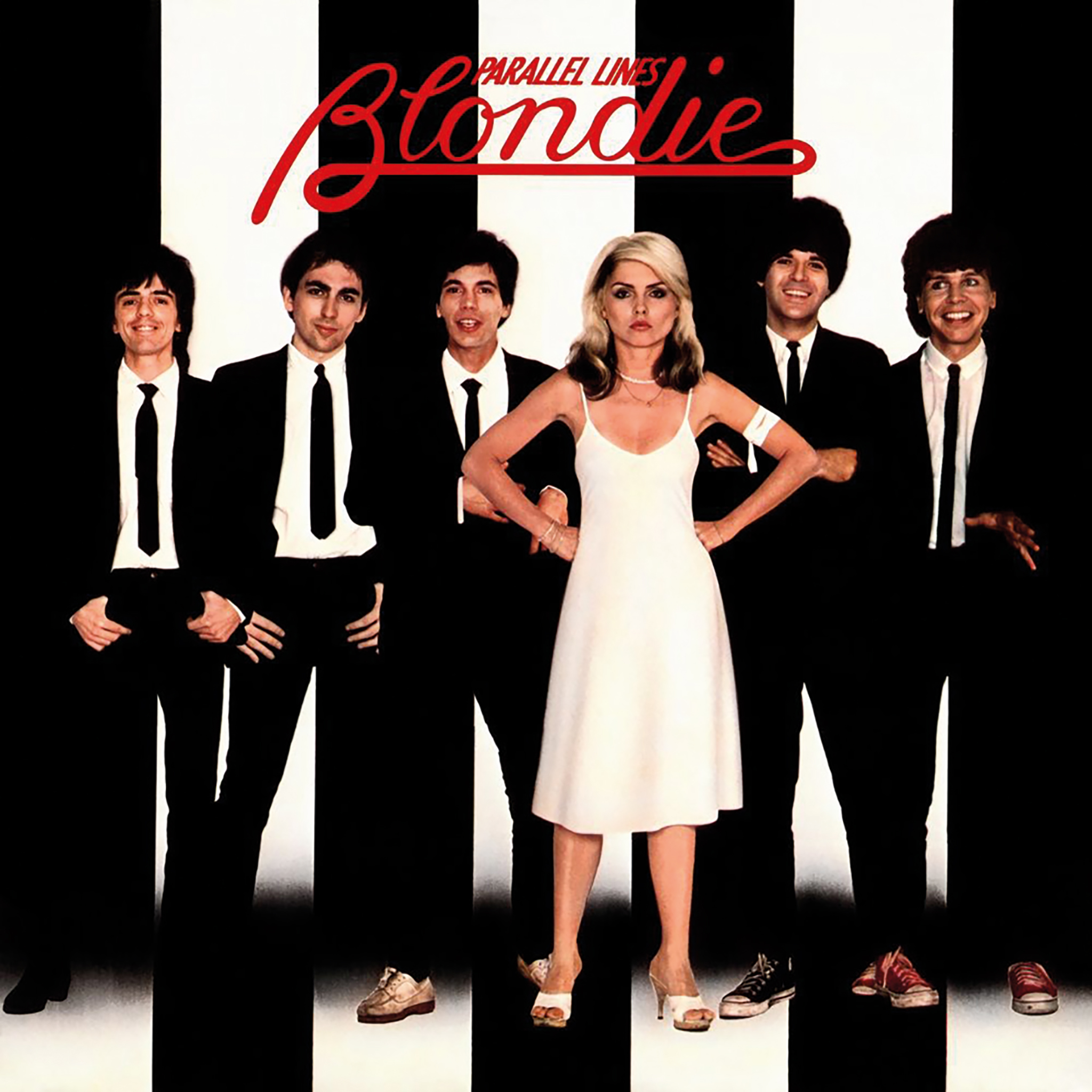

The label had an enormous post-prog afterlife. By signing Blondie it became one of the most successful labels in the UK, reinforced by the signing of the Midge Ure-led Ultravox, Spandau Ballet and Generation X. The licensing of 2 Tone was important too, putting the label at the forefront of a musical and cultural revolution in the UK. Ellis also took Billy Idol to the US and established him as one of the biggest stars of the early 80s, his photogenic snarl chiming perfectly with the rise of MTV.

Ellis and Wright sadly fell out during the 80s, when Ellis came back to Britain and Wright noted in his autobiography that “we were beginning to fall out over everything and nothing.”

Wright was ruefully to observe that “the two or three years we had been fighting was not a good time for Chrysalis. By 1980 we were a much bigger company than Virgin, but by the time Terry and I split in 1985, they sailed right past us.”

After buying out Ellis in 1985, Wright brought Nigel Grainge’s Ensign Records into the fold and gave the label an enormous worldwide hit with Sinead O’Connor’s Nothing Compares 2 U. Chris Wright sold the Chrysalis Records label to EMI in 1991. Wright left and EMI kept the imprint running with ex-Take That bad boy Robbie Williams. Initially seen as a laughing stock, Williams soon removed the smirk from his critics’ faces with his postmodern end‑of-the-pier show that was such a hit with European audiences.

Wright formed the discrete Chrysalis Group, set up boutique indie label Echo and, briefly, the heritage label Papillion, which was the imprint Cliff Richard was signed to for his final UK No.1, The Millennium Prayer.

TODAY:

The label was divested by Universal when they bought EMI in 2013. Warners looks after the UK-signed catalogue acts through the Parlophone Label Group, while the US material, such as Blondie, is through Capitol, run by Universal. The publishing arm was purchased by BMG Rights.

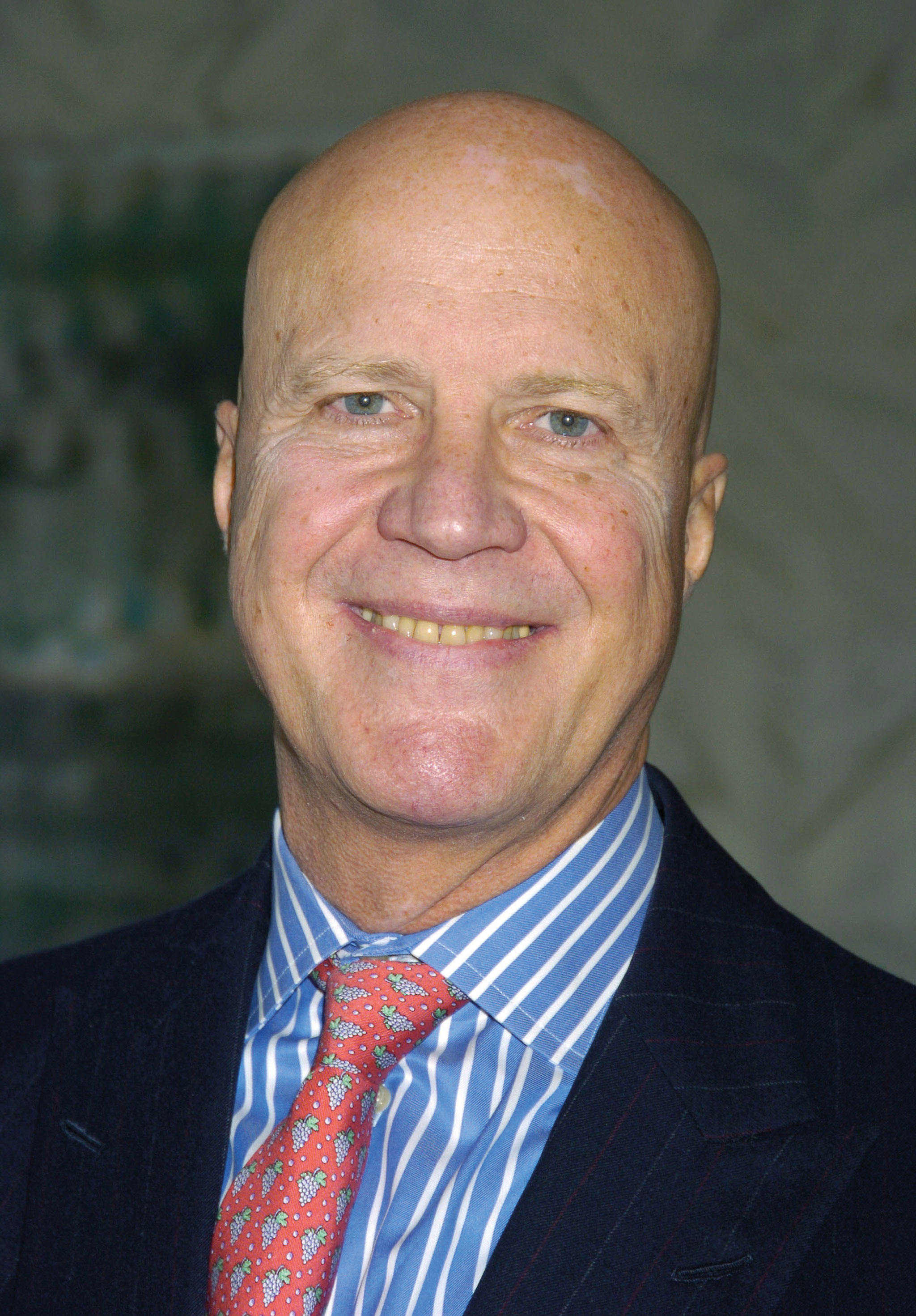

Wright is a multi-millionaire businessman with interests in radio, TV and sport; Ellis went on to found Imago Records and has served on the board of directors of the Metropolitan Opera Club of New York City.

WHY WE SHOULD CARE:

Chris Wright and Terry Ellis are maybe less well known than counterparts such as Richard Branson (described as a businessman pretending to be a music man, while Wright has been described as a music man pretending to be a businessman), but their drive and foresight saw them accepted into the industry firmament in a way their peers possibly weren’t.

Their open-minded musical policy led to a remarkable eclecticism and loyalty to acts such as UFO and Robin Trower, while also diversifying into video – Eat To The Beat by Blondie boasted the first full-length video album – and TV production: lest we forget, it was Chrysalis Visual Programming that brought Max Headroom into the world.

Chrysalis Facts:

The details behind the label.

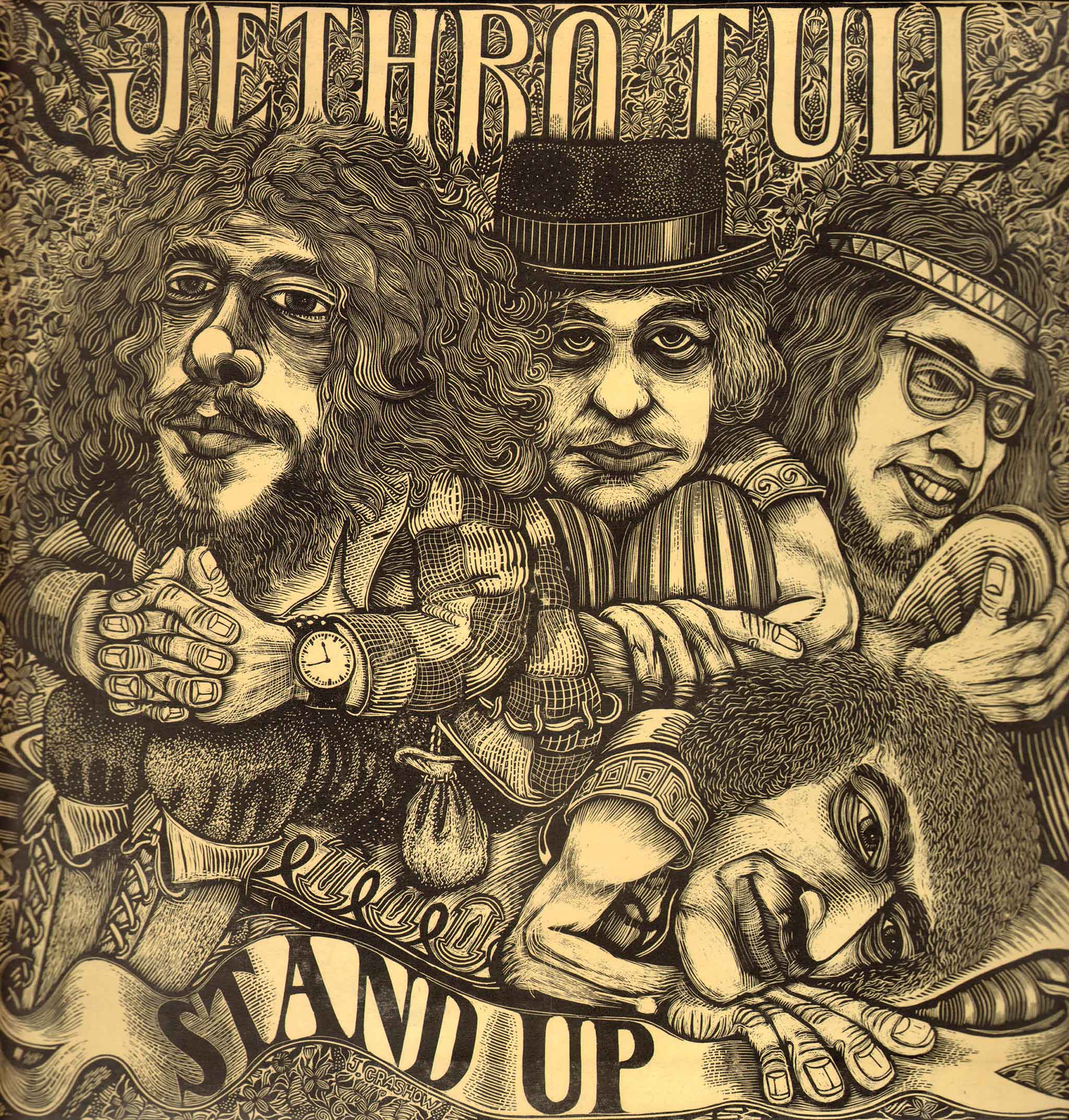

First album release: Stand Up by Jethro Tull (Island ILP 985, 10⁄68, pink label with Chrysalis Productions butterfly on it)

First single release: A Song For Jeffrey by Jethro Tull (Island WIP 6043, 10⁄68, pink label with Chrysalis Productions butterfly on it)

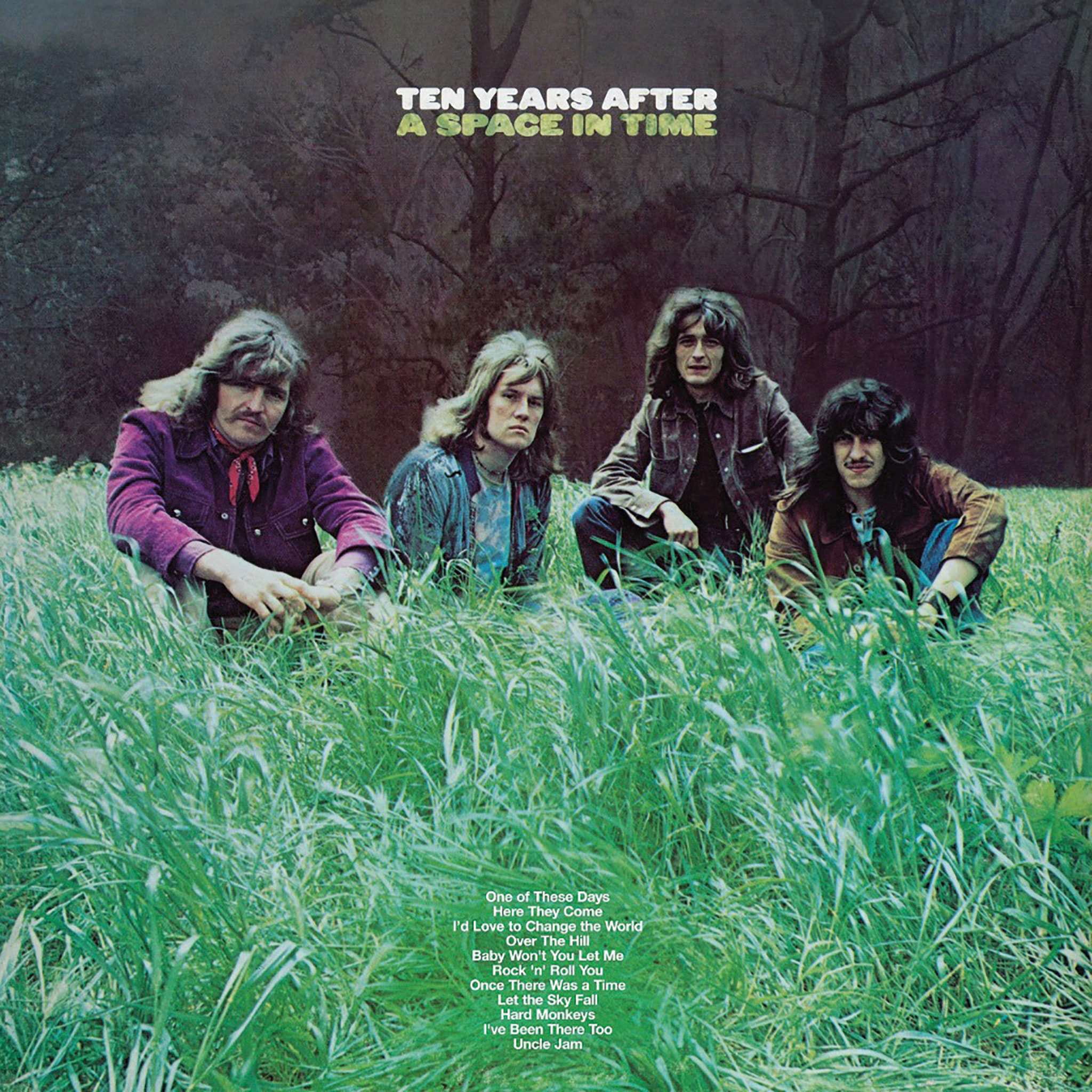

First album release on stand-alone Chrysalis: A Space In Time by Ten Years After (Chrysalis CHR 1002, 10⁄71)

First single release on stand-alone Chrysalis: The Lady I Love/Heidi by Tir Na Nóg (Chrysalis CHS 2001, 3⁄72)

First UK No. 1 album: Stand Up by Jethro Tull (Island ILPS 9103, 9/8/69, pink label with Chrysalis Productions butterfly on it)

First UK No. 1 single: When I Need You by Leo Sayer (Chrysalis CHS 2127, 19/1/77)

Last No. 1 single: Radio by Robbie Williams (Chrysalis CDCHS 5156, 10⁄2004)

Further Listening

The albums and tracks you need to hear.

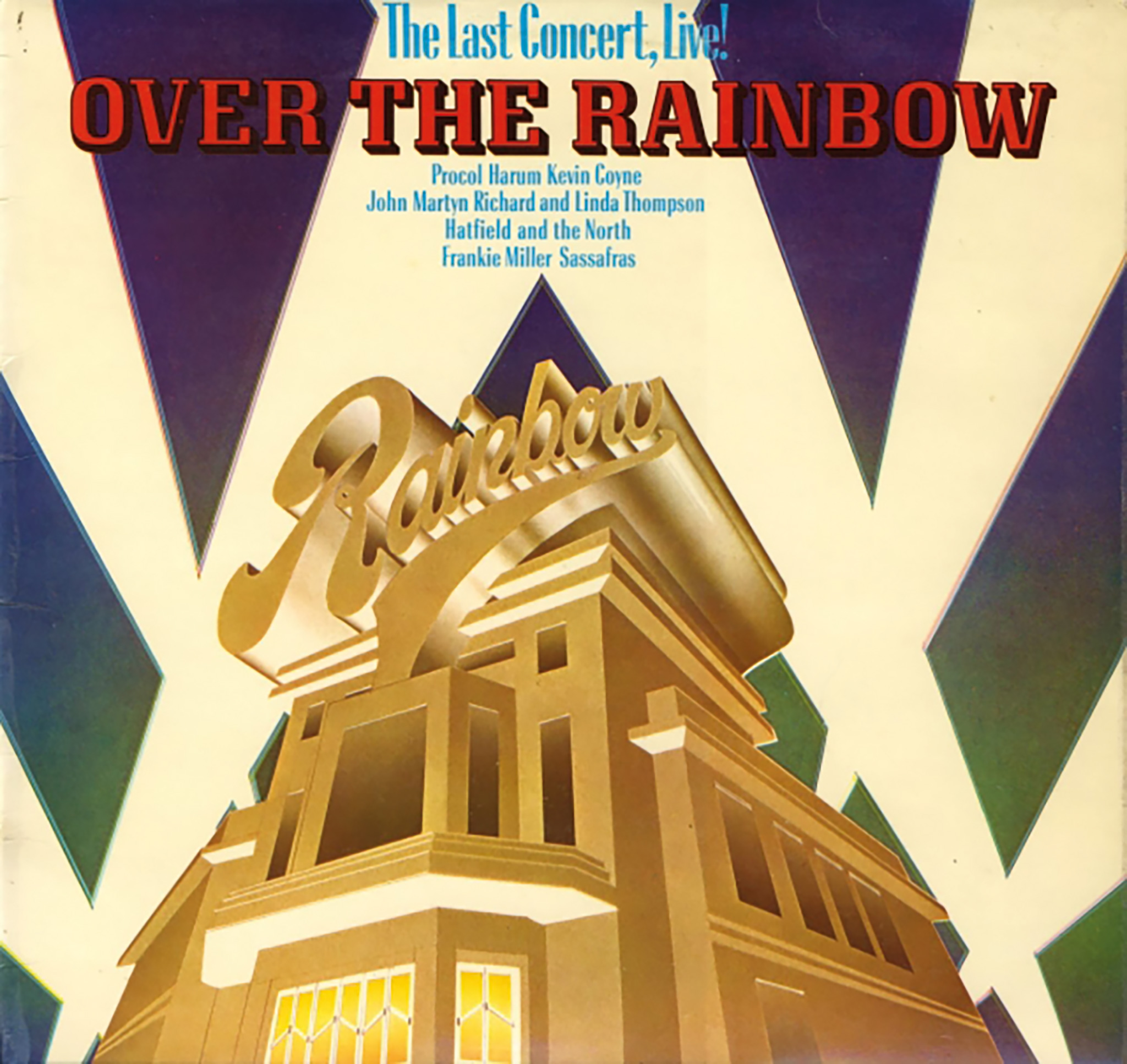

Various Artists

Over The Rainbow: The Last Concert, Live!

(Chrysalis 1975)

Under management company Biffo, Chris Wright and Terry Ellis owned the Rainbow Theatre in London, and this album was a live recording of its final show after it was threatened with closure in 1975. Featuring Chrysalis artists (Procol Harum, Sassafras, Frankie Miller and Richard and Linda Thompson) and some fellow travellers (Kevin Coyne, Hatfield And The North and John Martyn), it’s a marvellous showcase of the age, complete with super-earnest stage announcements by John Peel.

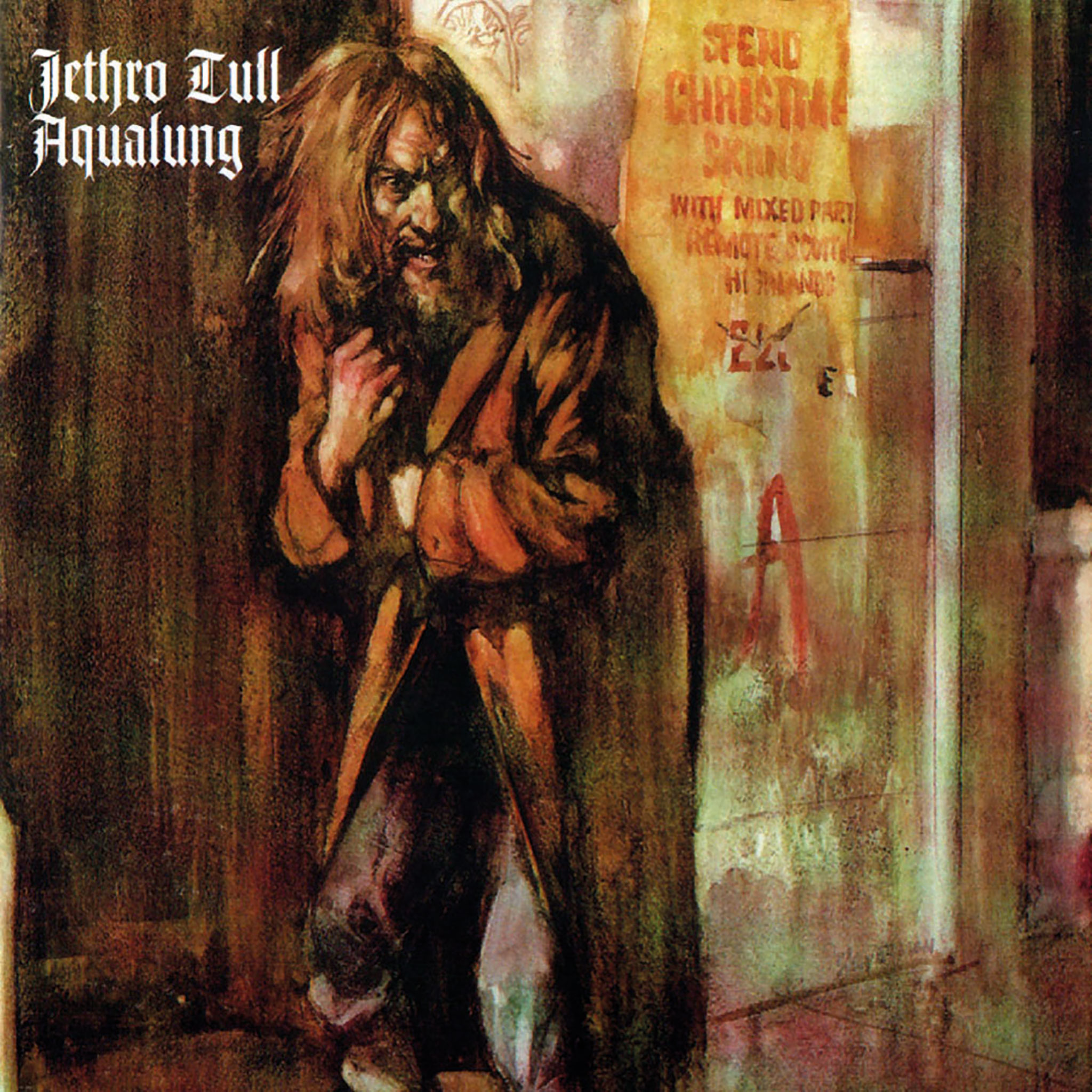

*Aqualung*

Jethro Tull

(Aqualung, 1971)

It’s impossible not to consider Tull when discussing the label. The title track from their not-a-concept-album Aqualung remains as bold and dark as it did when Ian Anderson first unleashed it in 1971. The album confirmed their position as Chrysalis’ superstars.

*I’d Love To Change The World*

Ten Years After

(A Space In Time, 1971)

Ten Years After were crystalised in the popular consciousness when the group were captured in all their split-screen glory in the Woodstock film, and Alvin Lee was mentioned in the same breath as Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page. I’d Love To Change The World became their only UK Top 40 hit on the back of this popularity.

*Free Hand*

Gentle Giant

(Free Hand, 1975)

Five years and three labels into their career, Gentle Giant delivered some supercharged performances on their first album for Chrysalis. The title track successfully captures their live aggression.

*Pandora’s Box *

Procol Harum

(Procol’s Ninth, 1975)

Procol Harum were industry veterans by the time they released this record, which boasts a mysteriously chugging sound that showed they could roll with the shifting demands of the mid-70s music scene.

*Fade Away And Radiate *

Blondie

(Parallel Lines, 1978)

Possibly the most astute of all Chrysalis signings, Blondie became one of the biggest groups in the world as the 70s became the 80s. Although their singles bristled with disco and power-pop, art rock was never far away, and this track from 1978’s Parallel Lines album features none other than Robert Fripp on guitar.

Street Cafe

Icehouse

(Love In Motion, 1983)

Led by polymath Iva Davies, Australian art-rockers Icehouse had a UK Top 20 hit with Hey Little Girl in 1983. Street Cafe, from 1983’s Love In Motion album, was its follow‑up. It’s one of the great overlooked songs of the 80s, with its sweeping arrangement and its Ferry-lite vocal delivery.