Outside of the traditional major labels, Virgin is probably the one record company the person in the street will be aware of. And that is, of course, due to the charisma of its founder, Richard Branson.

No matter how many years have passed since he tended the day-to-day, or the fact that a team of people, most notably Simon Draper and Nik Powell, ran the enterprise for him, the label is often associated solely with the adventures of Branson. With his unique blend of everyman and superman, his unparalleled capacity for PR saw his baby undergo several rebirths across its long history.

Although the label was sold firstly to EMI in 1992, Branson was still highly visible in celebrating Virgin’s 40th anniversary in 2013. Through a mixture of astute A&R, luck and circumstance, it has a remarkable ability to find, or court away from other labels, towering acts within their genre, such as Mike Oldfield – who, lest we forget, kept the operation afloat in its early days with the success of Tubular Bells – Tangerine Dream, the Sex Pistols, The Human League, Phil Collins, Culture Club, the Rolling Stones and the Spice Girls.

Branson has remained astute, which goes all the way back to his first venture, the Student magazine. When his overdraft was running high, his bank manager told him in no uncertain terms that investors always have to be looked after. “I’ve very much remembered that. It gave me a bit of a fright,” he told Paul Rambali in 1984.

HOW IT BEGAN:

Stowe-educated Branson showed early entrepreneurial skills and, as biographer Tom Bower suggests, “unlike his friends raging against the Vietnam war, Branson was a putative trader in search of ideas that would earn him money”.

Although he wasn’t a music fan, he saw that there could be money in a record label and a recording studio. He had been the editor of Student, and hit upon the idea of selling records by mail order, taking full advantage of the abolition of the Retail Price Maintenance Agreement.

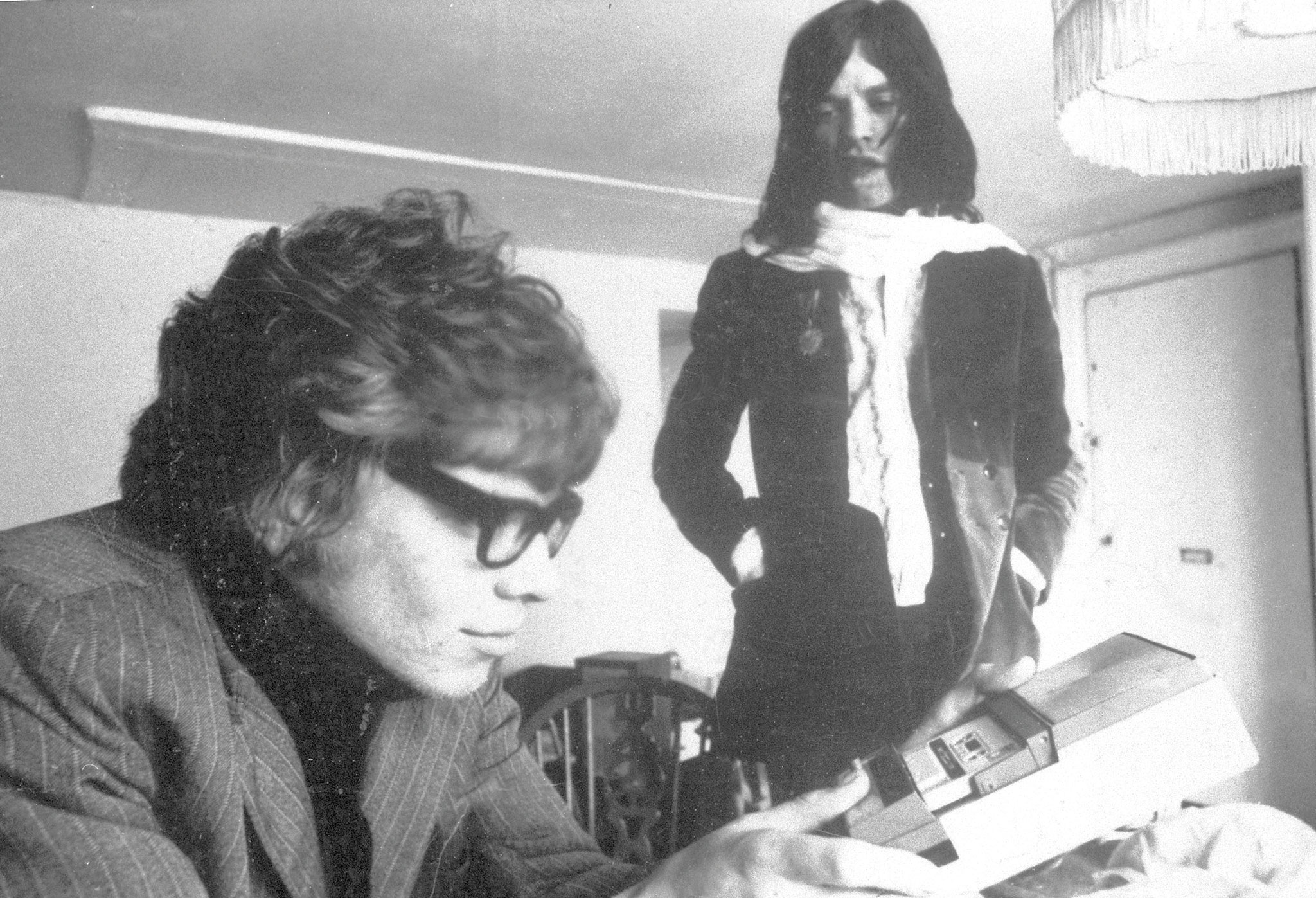

Virgin was born. The name arose from Virgin office staffer Tessa Watts, who suggested that they were virgins in business. It was soon to expand: Draper recalled to Prog that Branson “took me out to lunch and described to me his plans for a recording studio, a record label, a publishing company and a management company. It all sounded very ambitious and rather unlikely to me.”

The initial success of the mail order business led to the opening of the very first Virgin retail outlet on London’s Oxford Street. The store reflected the times: beanbags, joss sticks and headphones meant a customer could sprawl out and, like, be.

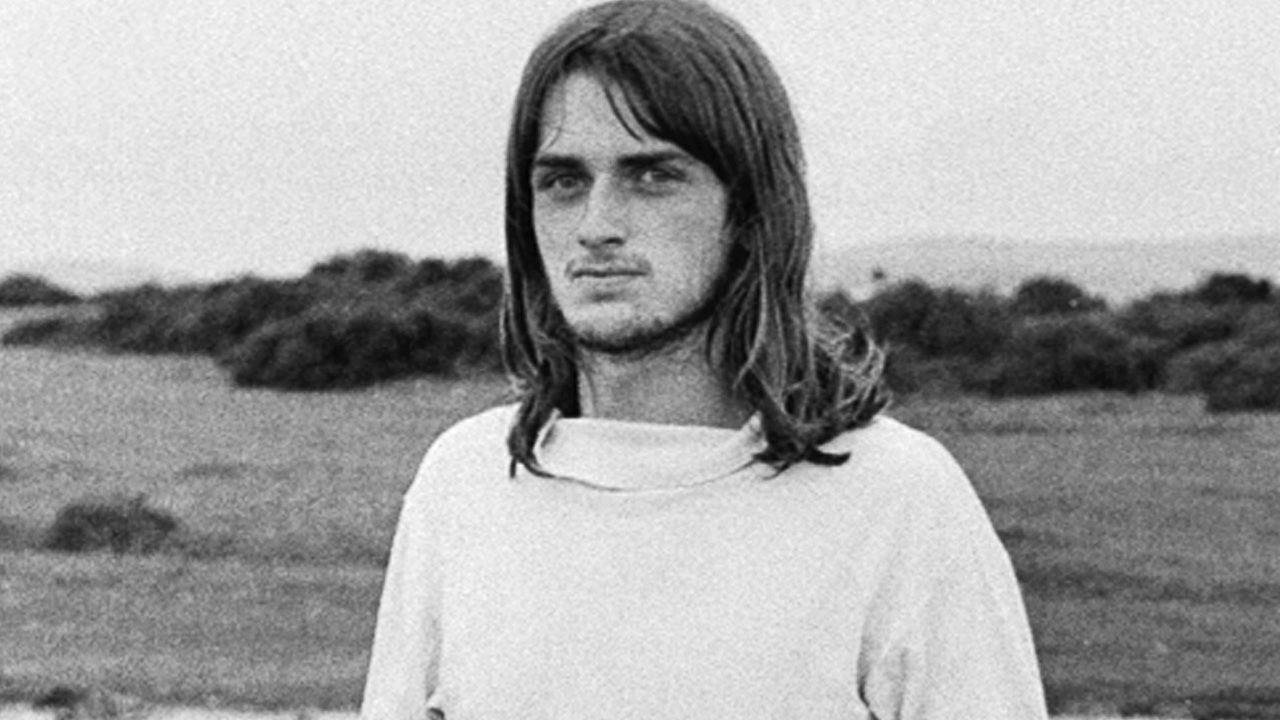

Plans were made to acquire a recording studio in Oxfordshire, The Manor, and set up the label. But what indeed would be its premiere release? An instrumental suite, Opus One by the 19-year-old Mike Oldfield, who had been Kevin Ayers’ bass player, was brought to Branson and Nik Powell’s attention by producer Tom Newman.

Oldfield was given downtime at The Manor, and Opus One’s fate was sealed when Oldfield spied the tubular bells, which had been hired for John Cale’s Academy In Peril, being removed. An idea was hatched. Tubular Bells – as the album, of course, became – was one of four releases that came out on May 25, 1973, all testament to Simon Draper’s adventurous A&R policy. The others were The Faust Tapes, which sold for 49p and introduced Krautrock into the homes of 100,000 people within its first month; Gong’s The Flying Teapot, which built on the success of Camembert Electrique; and the Manor Live, a jam album by ‘Camelo Pardarlis’ with characters such as Lol Coxhill, Elkie Brooks and Boz Burrell. Tubular Bells rolled on and on. The record stores would expand and, for many, that was their interface with the Virgin brand.

“It’s hard now to get across what a big deal those stores were – not every town had one and you felt privileged if there was one in your town,” Mitchell Edmond, who worked in Virgin shops from the 70s to 80s, recalls. “And also how central records were to most people’s lives. Music and records were cool, Virgin stocked records and magazines you couldn’t buy anywhere else and, particularly in a smaller store, and in a smaller town like Swansea, Virgin became the place for like-minded and young, impressionable souls to meet. It was literally like a grown-up youth club.”

THE GOLDEN PERIOD:

Tubular Bells, as we know, became a global phenomenon when its opening theme was used in William Friedkin’s movie The Exorcist. The absolute maverick spirit the label had was reflected in its A&R policy. Former Marketing Director John Varnom says on Virgin.com: “In an age now when most companies have every single release triple-checked by lawyers, accountants and middlemen, it’s refreshing to see how much freedom we had.”

Branson personally signed Tangerine Dream because of how well their imports sold and he firmly believed that they could be “as big as Floyd”.

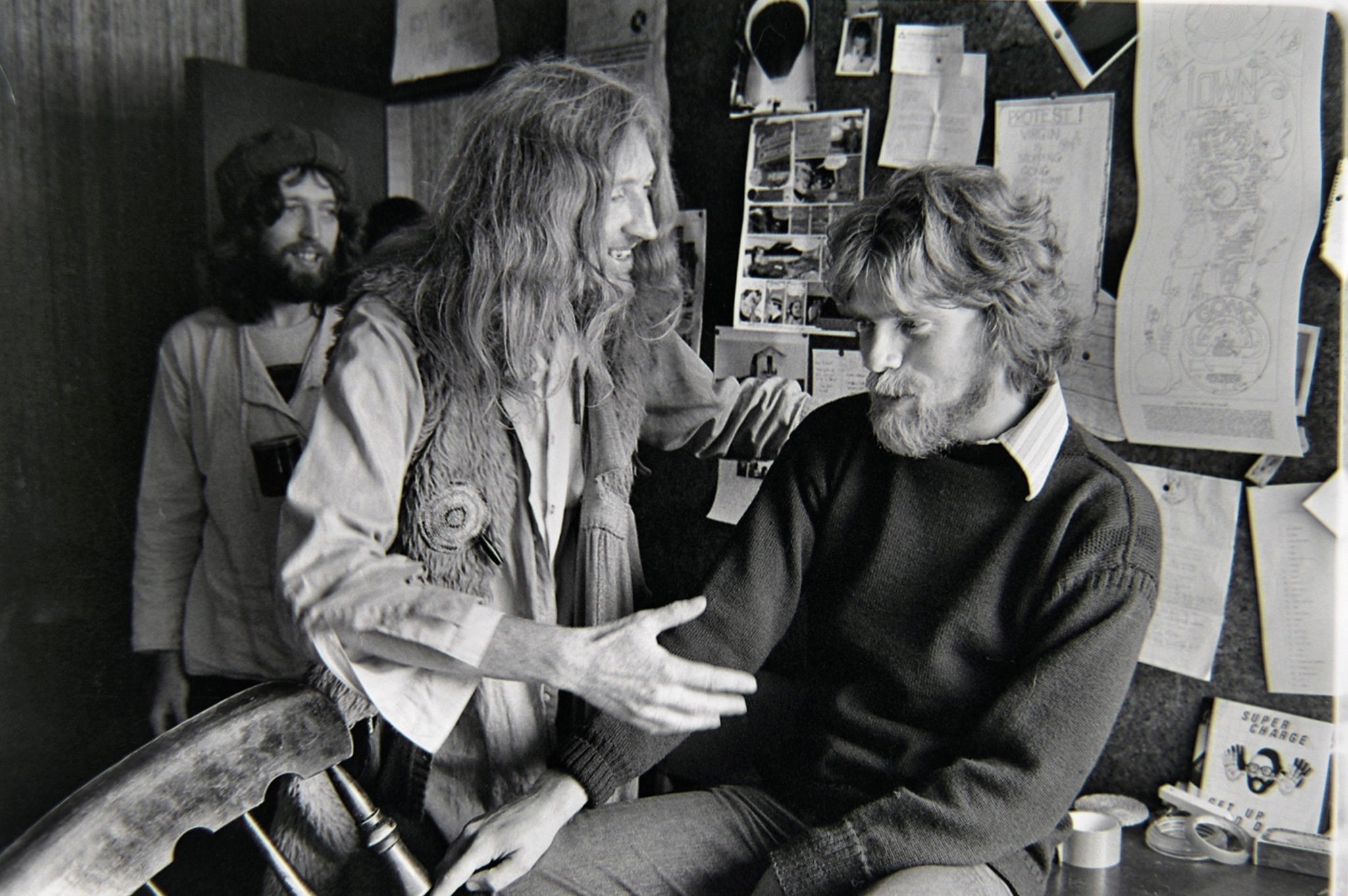

“We thought it was dead easy,” Simon Draper said in 1984. “I thought we’d be able to consistently sell records by unconventional, difficult people. I indulged my fantasies of being able to make records with heroes of mine, people like Robert Wyatt.”

Branson said in 1984: “Simon loves records and his whole involvement is through that. With me it’s different. It’s not a love of music. I enjoy people, I enjoy working with friends, I like finding out about new things, new areas I know nothing about.”

With bands like Hatfield And The North, Egg and Henry Cow, Press Officer Al Clarke described Virgin in this era as being the equivalent of an “audio Arts Council”.

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT:

Oldfield’s ongoing success bankrolled some of the label’s more extreme acts, and the Sex Pistols’ much-vaunted signing in 1977 gave the label new credibility among punks, with Branson epitomising the ‘never trust a hippy’ ethos of Malcolm McLaren. The label embraced post-punk, with acts such as the Skids and Magazine.

Virgin also played a key role in distributing labels such as Stiff. “Virgin was like an older brother to us,” Paul Conroy, Stiff’s General Manager (who would go on to be Virgin’s MD in the 90s), says. “They had more money, structure and acts than us. They enabled us to get into the shops via their sales force and therefore have hits.”

Virgin really stepped out of the prog shadows with the success first of The Human League and then Culture Club’s unprecedented US triumph. Phil Collins signed as a solo artist to Virgin in the UK and enjoyed a stellar career.

Branson realised the power of the brand and by using the best mavericks in their field, along came – with varying degrees of success – Virgin airlines, cola, vodka, trains, cosmetics, condoms. The shops became megastores, thrusting retail operations that subsumed the Our Price brand, run by operations people with checklists – and with considerably less love for Mallard than their predecessors.

“The sea change in public interest really came in the mid-80s when the airline started and made him a household name,” Edmond says. “Then the stores were selling Virgin condoms, there was RB’s newsworthy plot with Thatcher to clear the UK of litter, supermarkets selling Virgin coke and a constant stream of new businesses launched under the Virgin name, always with a wacky PR stunt featuring RB, always with a leggy lovely, in a costumed attempt to get on the front pages.”

Back at the old business, in 1983 Charisma came under Virgin’s wing, bringing with it the catalogues of Genesis and Peter Gabriel. The year was also the label’s best to date, with Culture Club going from strength to strength, but also with Oldfield delivering Moonlight Shadow, which was one of his biggest hits.

In 1992, the label was sold to EMI and Paul Conroy took over as MD. “Some of the ghosts did float around – and the ‘Well, we’ve always done it that way’ people – but we adapted to the new situation and managed to go on and break many new artists,” he explains. “It was a mixture of some great Virgin institutions like the Friday HODS [Heads Of Department] breakfast meeting and a more focused company with a tight set of labels and a brilliant team.”

Conroy left a decade later.

TODAY:

Still very much a going concern with artists such as Naughty Boy, Catfish And The Bottlemen and Bastille. When EMI was sold in 2012, the Virgin label moved across to Universal and was merged with EMI, creating VirginEMI, incorporating Mercury Records. Virgin’s heritage is well tended.

And the Virgin brand itself? From Virgin Media to Virgin Galactic, the proposed first commercial space travel line, to banking, health provision and beyond, it’s simply inescapable.

WHY SHOULD WE CARE:

Although relatively late to the world of label set-ups, Virgin introduced the notion of the hippie entrepreneur. Richard Branson is now one of the most recognised figures in the world, and his astute marshalling of people who know how to run stuff has seen him build many businesses, all of which are loosely based on the original Virgin model.

The fact that many assume he has a close involvement with every business is testament to what he and his team created. However, it would have been nothing without the power and the mystical allure in the first instance of Tubular Bells. The album kept the label afloat through its early years before the Pistols and then the full commercial rebirth of the label in the 80s.

Oldfield in the 70s, The Human League and Culture Club in the 80s, Spice Girls in the 90s, to Emeli Sandé in the 00s, Virgin always seems able to locate the big hitters. But for many, it will always be epitomised by that free spirit encapsulated by the record stores. Succeeding where others didn’t, the stores were a living embodiment of your taste. Yeah, man.

Virgin Facts:

The details behind the label.

First album release: Tubular Bells by Mike Oldfield (Virgin Records, V2001, 5⁄73)

First single release: Marlene/Everybody Says by Kevin Coyne (Virgin Records, VS102, 8⁄73)

First UK No. 1 album: Hergest Ridge by Mike Oldfield (Virgin Records V2013, 9⁄74)

Fascinating fact: Hergest Ridge leapfrogged Tubular Bells to No.1 in September 1974, then Tubular Bells went to No.1, replacing Hergest Ridge. It was the first time at No.1 for Tubular Bells, 16 months after its release, at the apex of Oldfield/Exorcist mania

First UK No. 1 single: Don’t You Want Me Baby/Seconds by the Human League (Virgin Records VS 466, 11⁄81 – No.1 for five weeks. It was US No.1 for three weeks in June 1982)

A curio: The Womble Bashers/Womble Basher Wock by The Bashers (Virgin Records VS 154, 6⁄76 – the band’s name was a pseudonym for Mike McGear and Roger McGough, and the song was re-recording of a Grimms album track.)