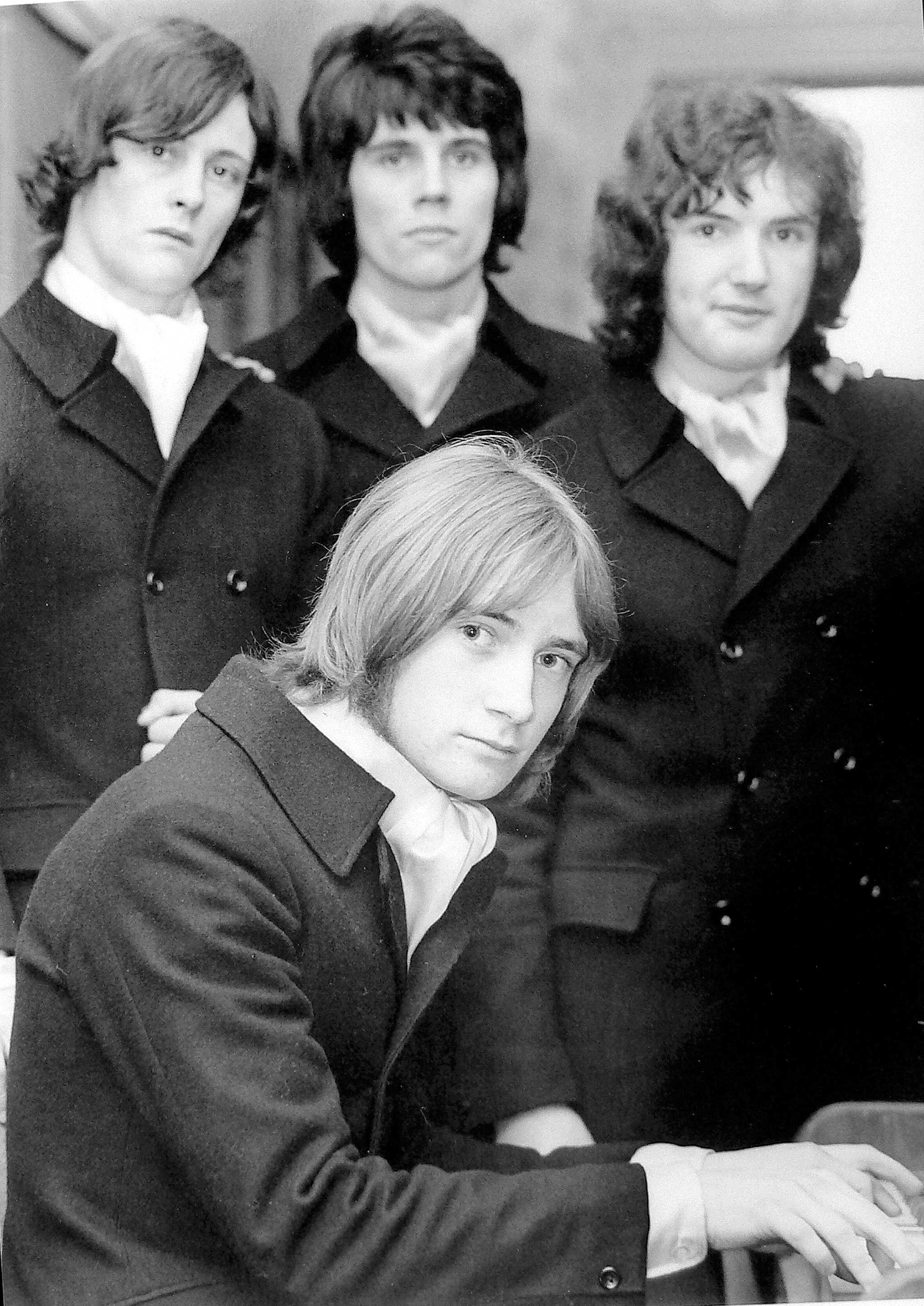

Like most rock musicians of a certain vintage, Phil Collins can’t escape the past – or his own image. Hanging on the wall in a corridor of Warner Music’s London office is a portrait of a younger Collins, frowning quizzically into the camera lens.

Today, the 65-year-old Phil Collins, seated in his record company’s lounge-cum-meeting room, looks older than his picture. Due to a broken bone in his foot, he’s walking slowly with a stick. But his mind is as quick as ever.

“This is for Prog magazine, right?” he asks cheerily, easing himself into a sturdy chair, stick nearby – so he can whack your correspondent if he asks too many questions about Nursery Cryme, perhaps?

And yet here’s the thing. Officially Collins is here to discuss his reissued 1982 and 1996 solo albums, Hello, I Must Be Going and Dance Into The Light. But he’ll talk about anything. The old stuff, the not so old stuff, Genesis, Peter Gabriel and his own 150-million-selling solo career. To Phil Collins it’s all music, and his music has never fitted into a box.

It’s been a long day of interviews and the man from The Guardian has only just left. But rest assured, this will be the only interview where Phil Collins can talk about specific movements in Supper’s Ready and obscure Brand X album tracks (are there any other kind?) and be certain that the readers will know exactly what he’s talking about. Turn it on again, Phil…

Do you remember the first song you ever wrote?

It was called Lying, Crying, Dying, and it was in D minor, the saddest of chords [grinning]. No, it really was in D minor. It was a very naïve but heartfelt ballad. This would have been in the late 60s when I was 15, 16 years old. Then I dried up until the mid-70s.

You just stopped for a few years?

Yes. But around that same time I wrote a thing that later became Lilywhite Lilith on The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway. I also had a bit of something that later became Why Should I Lend You Mine (When You’ve Broken Yours Off Already) for [jazz rock side project] Brand X. It’s funny how those bits only surfaced in later life.

Was it hard to break Genesis’ Peter Gabriel-Tony Banks-Mike Rutherford songwriting clique?

The spirit of Genesis was Tony, Mike and Peter. I didn’t regard myself as a songwriter then. But there were things in Genesis I was highly influential in. My strength was arranging.

What inspired that?

I was very into the first line-up of Yes – the one with [guitarist] Peter Banks. I remember listening to them and loving the way they took other people’s songs – Something’s Coming, Every Little Thing – and did something different with them. I thought, “That’s something I could do,” so I brought that influence into Genesis.

Was there ever a sense of “You’re just the drummer, Phil” from the other band members?

Not really. But I was this interesting square peg in a round hole. I was the joker, the class clown at the back. But I was also the only person who played with other people. [Laughing] I really was Genesis’ only contact with the outside world.

How did this help the band?

It was through me dallying around and playing with other people that I introduced them to [producers] David Hentschel and later Hugh Padgham. I was always the one searching around and looking outside the bubble. But they encouraged it. I read something in Mike’s book [his autobiography, The Living Years], where he wrote, “If Phil had an idea, you listened…” I was very touched by that.

You’ve read Mike’s book then. What did you think of it?

I enjoyed it very much. But when I first read a review, it didn’t occur to me that I’d be in it. It never dawned on me.

Really? Come on…

Honestly. I just thought, “Oh, Mike’s doing a book…” But when I realised I was in it, I thought I’d better see what he said. So it was illuminating to read that line. I never thought he’d say something like that.

Was there anything in it that you didn’t particularly like?

I had no issue with it at all. Tony Banks had a few, but I’ve no idea what they were – probably stuff going back to when they were at school together. Steve [Hackett] has talked in the past about how he and I were the junior partners in Genesis.

Standing back and watching the three old school friends having an argument?

Yes! “You stole my protractor!” That was a very good description of it.

How much did you contribute to writing the first songs you sang with Genesis, For Absent Friends and More Fool Me?

Yeah, they let me sing a couple – “Keep Phil happy… throw him a bone!” [Laughs] Me and Steve wrote most of For Absent Friends. More Fool Me? [Pause] God, I had completely forgotten about More Fool Me. I think I wrote some of the lyric but it was mostly a Mike song. I honestly didn’t consider myself a songwriter until [1981’s first solo album] Face Value. That’s when I earned my stripes.

So what do you think of the songs that you co-wrote for Genesis before then?

Wot Gorilla on Wind & Wuthering was my baby, and Los Endos on A Trick Of The Tail. Again, it was about ideas and arrangements. I’d heard the Santana album Borboletta, and there’s a tune on it called Promise Of A Fisherman. If you’ve got it on your iPod, have a listen and think of Los Endos. That’s where it came from – I was more involved in that.

When you started making solo albums, were you torn between giving songs to Genesis and keeping them for yourself?

No, because when we were making Duke [in the winter of 1979] I still didn’t know I was making a solo album. Genesis took Please Don’t Ask and Misunderstanding. If they hadn’t, they’d have been pivotal songs on Face Value – that’s why we included the demos when we reissued it last year.

Hence the ongoing argument about whether you actually played them In The Air Tonight. Shall we keep it going here?

[Laughing] Ah yes, the long-standing dispute. It’s unlikely I’d have held that back. More likely they forgot they’d heard it, because there were only three chords in it.

Looking back, it does feel like you had a solo career by accident rather than design.

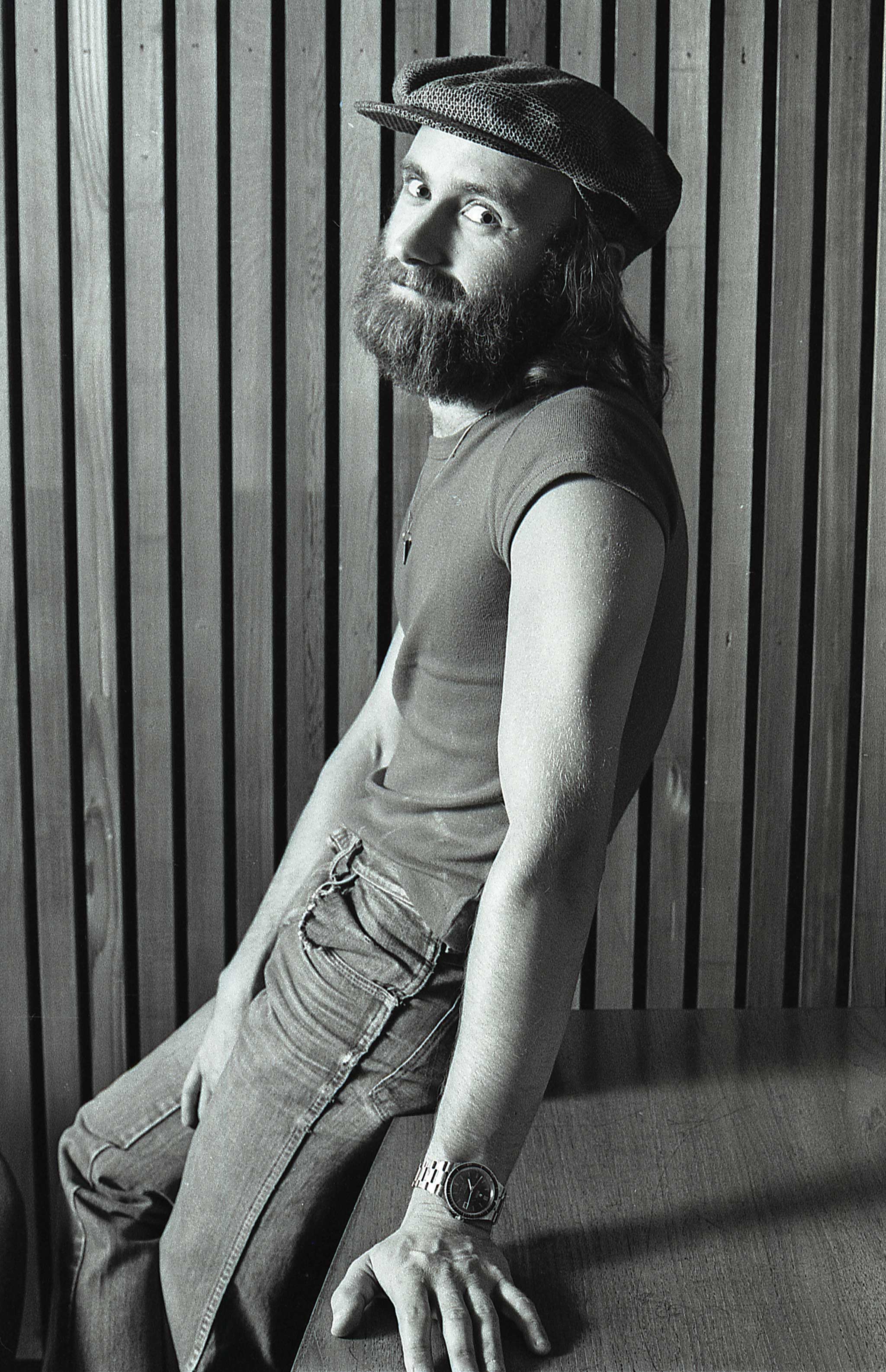

Yes. Had the personal stuff, getting divorced [from first wife Andrea Bertorelli], not happened, I don’t know if I’d ever have made a solo record. I was playing with Brand X at the time, and if I’d made any sort of solo record, it would have been more along those lines – but more elegant, more Weather Report and Wayne Shorter than the frenetic stuff Brand X did.

Saying that, you put some distance between Genesis and your solo records. Did you deliberately sign a solo deal with Virgin rather than sticking with Charisma?

It was deliberate, yes. I didn’t want to divorce myself completely – ’cos I stayed in the band – but I did want to distance myself. I thought if people saw there was a solo album by the bloke from Genesis on the same label as Genesis, they’d say, “Oh, I know what that’s gonna sound like.” I also loved the Sex Pistols, who were on Virgin. So Virgin were seen as edgy, and I wanted edge.

Around the time you were making Face Value, you were hanging out with John Martyn, who’d also split from his wife. There must have been some lively nights?

Yes, with John Martyn and Eric Clapton. I was doing Grace And Danger with John, and he said [whispers, grinning], “I wonder if Eric’s got ‘anything’.” So he called Eric and he said, “Don’t come to the house,” ’cos he knew if John turned up, he’d never leave. So we met in a pub in Guildford. That’s how I got to know Eric – as a friend. We worked together later, but I was just this bloke to have a laugh with, one of his Ripley pals.

Revisiting Hello, I Must Be Going again, one minute you’re singing You Can’t Hurry Love, the next you’re ranting angrily on I Don’t Care Anymore and listening to the neighbours having sex on Thru These Walls.

It was always about more than You Can’t Hurry Love. [Emphatically] I have been saying this for years because everybody judged me by what they heard on the radio and didn’t go any deeper. It’s gratifying to hear that people are picking up on this now because that was the point of these reissues. I was never just about the hits. But those were the songs everybody heard. There’s such a diverse bunch of songs on Face Value and Hello, I Must Going, which you wouldn’t get nowadays.

There seems to be a lot of pain in Do You Know, Do You Care. Presumably that was to do with the break-up of your marriage?

I had forgotten how angry those songs were… because, yeah, by this point we had split up and [laughing] the lawyers were involved. But I wasn’t as aware as other people of the anger. By the time I recorded the songs, I’d got a lot of that anger out of my system, and it didn’t seem like such a huge jump from that to You Can’t Hurry Love.

Does the personal subject matter make it difficult to listen to these songs now?

Not really, because these albums have all been in my head on and off for some time. I haven’t heard these remasters. I was involved in choosing the demos and live material, but I left the remastering to [producer] Nick Davis, because I’ve only got one-and-a-half ears. But I revisited these songs when we were on the road to see if there was any material we could do.

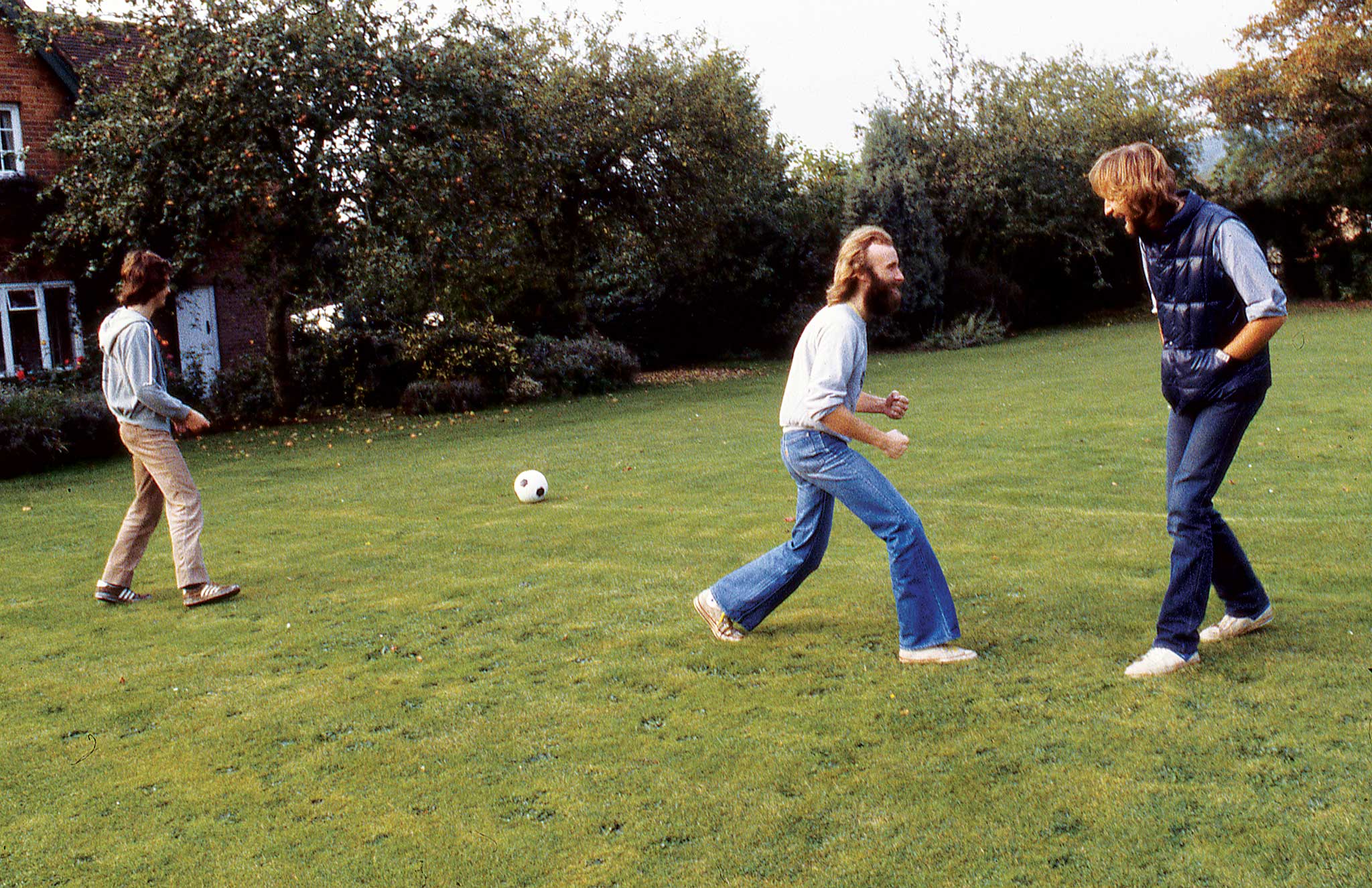

Mike Rutherford admits that when you started having solo hits, there was some jealousy from the rest of the band.

Yes. Tony Banks said, “We wanted him to do well, but not that well.” It’s natural. We’d started doing Abacab, Face Value was out and suddenly it started doing its thing. I was excited, but every day I’d go down to The Farm [studios] with the rest of them and really try and keep it down. I would try, but then it would slip out, “Oh, In The Air Tonight’s just gone to No.1 in Holland…” I was a bit embarrassed.

Why embarrassed?

Because Tony and Mike had both made solo albums [A Curious Feeling and Smallcreep’s Day respectively]. Mine was selling for the obvious reason, in my head, because everybody knows the singer – and I was the singer, and Tony and Mike didn’t really sing on their albums.

There are obvious parallels between some of your songs and what Peter Gabriel was creating around the same time.

There was a time when we were running parallel, yes. I think people forget that sometimes. You know what happened with Intruder [Gabriel’s 1980 song on which Collins and Hugh Padgham pioneered the ‘gated drum’ sound]? When Peter first heard that sound – we called it the ‘facehugger’ like that thing in Alien – he got off the sofa and went, “What is that?” I said, “What are you going to do with it? That’s my baby.” He said, “I’m going to use it,” and I went, “Mmmm…” [mouse-like whimper]. Then Peter rewrote Intruder to fit the drum rhythm.

Did it bother you?

Well, I said, “Can I at least have a credit?” – which he gave me, a little begrudgingly, I think. What isn’t so well known is that I played drums in Peter’s band around this time because he couldn’t afford the American band. But I loved what Peter did. It was great fun. I remember spending a day playing I Don’t Remember. I loved that hook – “Ding‑ding-ding…” I said to Peter, “Why aren’t you playing that?” He said [impersonates Gabriel’s voice] “I don’t want to do that.” Peter would do things like that – like he was putting a tripwire in front of himself.

Was not letting drummers use cymbals on the album one of those tripwires?

“Nothing metal” was the way he described it. “I don’t want any metal on this album, Phil.” I was okay with it, but I didn’t know what to do with my left hand.

Isn’t it a bit annoying that Gabriel gets all the kudos and you don’t?

We were different animals. I was just trying to write the best songs I could, but you’re right, Peter got all the credibility… and I got the money! Ha. I’ve never said that before, but that does sum it up.

You’re reissuing your whole solo back catalogue. Today, what do you honestly think of the albums overall?

The next two to come will be [1985’s] No Jacket Required and [2002’s] Testify. I love Testify because what you hear is pretty much my demos. I have more problems with No Jacket Required – which, ironically, is one of my biggest-selling albums. It has some of my favourite songs – Take Me Home, Long, Long Way To Go, Only You Know And I Know – but it also has me trying to do something outside of my box, which was a couple of dance songs. Sussudio was my song, but I gave it to [keyboard player] David Frank to arrange and he put all the bells and whistles on. He made it sound like all the other records sounded at that point – with bells and whistles on.

What about Dance Into The Light, which is being reissued at the same time as Hello, I Must Be Going?

On Dance Into The Light I was trying to write from a guitar player’s perspective. I had some Rickenbacker samples on the keyboard, and I thought they would make me write different songs. Although I love some of those songs – It’s In Your Eyes, Love Police, That’s What You Said – it’s not really me. Other people, whose opinions I respect, have said, “It’s not really you, is it? Go back to the piano, Phil.”

You’ve previously mentioned feeling “uncomfortable” about your public persona in the 1980s. But wasn’t that ‘cheeky chappie’ Phil Collins necessary to sell songs in a big stadium?

Yeah, it was. I was an entertainer. I had the show-business background from being in Oliver! as a kid. And I loved doing that thing at Wembley [Stadium], getting 80,000 people to go “Whooah…” That was magical. But I just can’t particularly watch myself now. I find it very hard.

Why is that?

The problem is, some of the time, I found myself singing things I didn’t quite understand.

Are we talking about lines like ‘Sheets of double glazing help to keep outside the night’ in Domino?

Yes. That’s a Tony lyric. I found it tricky. I used to think, “How do I sing this thing about double glazing? How do I sing this and convince an audience?” I found it awkward, because I was getting more personal in my songwriting, and here I was singing things I didn’t understand – just syllables.

- Phil Collins: I would have quit Genesis for The Who

- Genesis: Foxtrot Was Where We First Started To Become Significant

- The Top 10 Greatest Prog Album Covers Ever

- Pink Floyd: The Story Behind Atom Heart Mother

You’ve ruined that song for the readers now!

But maybe it’s something other people don’t think about when they listen to the record… Sorry if I’ve spoiled it for anyone by bringing attention to it! All In A Mouse’s Night is another one [laughs]. But I can see what you mean.

Was that also a problem when you were singing some of Peter Gabriel’s lyrics?

There were certain things in the old stuff, sure. But I loved Supper’s Ready. Most of it, except for maybe Willow Farm, was well within my reach. I also loved Apocalypse In 9⁄8 because I got to play the drums – and we had two drummers. And that end section, the bit about ‘a new Jerusalem’, that was fantastic to sing.

Do you get fed up with constantly being asked whether Genesis will get back together again?

No, because that 2007 reunion was good.

So could you see yourself playing on stage with them again?

Right now, talking to you, I can see it. But it’s what happens when I get back to the hotel… I’ll go off the idea. But a Genesis reunion with Peter Gabriel? People should forget about that.

So there wouldn’t be a reformed Genesis with Peter Gabriel in the line-up?

Before the last reunion, we had this painful meeting in Glasgow, which seemed to go on forever. Mike, Steve, Tony and I were keen. But we couldn’t get any commitment from Peter. Also, straight away, I could see that if Peter was involved, with the technology available, it would have been a nightmare.

In what way?

I could see Peter coming up with all these abstract ideas and rubbing Tony up the wrong way. It would have been great fun for me, though, because I could have just sat at the back and played drums.

Mike Rutherford said afterwards that when Peter and Steve left the room, the three of you looked at each other and it felt like “This is the band”.

Yes, the three of us looked at each other and said, “Maybe just do it with us?” And in five minutes we’d made the decision.

You’ve had some health problems. Can you still play the drums?

The honest answer is: I don’t know. The last time I played drums was with Eric Clapton at the Albert Hall doing Crossroads for The Prince’s Trust [in 2010], and as soon as we started playing, da-da-dada-dah, I thought, “Ow, this is not feeling right.” But having talked for years about this and saying I cannot play the drums, I think I should get a little kit and practise.

Once all the reissues are out, what’s next for you?

My autobiography, which will be out in October. I started just after I finished writing the Alamo book [2012’s The Alamo And Beyond: A Collector’s Journey], because I was having fun and wanted to keep going. There’s been a lot of talking and we’ve got the story. It’s just a question of putting it all together.

What can we expect from the book?

It’ll be warts and all, I can promise that. It really will be the truth as I see it.

This article originally appeared in Prog issue 66