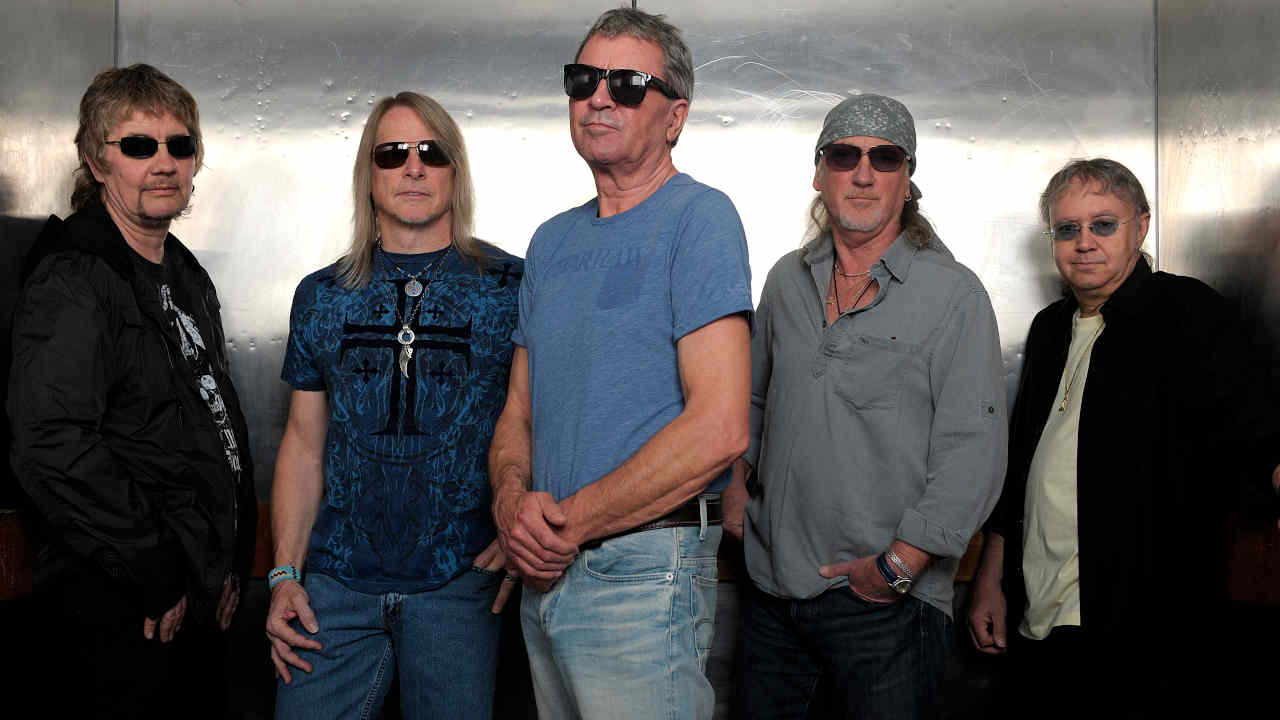

Along with Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple were the third in the holy trinity of bands who laid down the blueprint for hard rock and heavy metal in the late 60s and early 70s. In 2012, singer Ian Gillan and drummer Ian Paice looked back on the band’s turbulent history, tangled family tree and sometimes overlooked legacy.

By the early 1970s, the spiralling number of music sub-genres led to different movements lining up over each other to sign up new recruits. Whatever kind of freak you were, you had a home to educate you on which bands to listen to and which drugs to take. Space-cases and acid goblins flocked to Pink Floyd. Black Sabbath attracted doomsday occultists, schoolyard burnouts and advanced demonologists. Funky sex machines had James Brown. Pill-shovelling biker pigs and sci-fi weirdos fell in with Blue Oyster Cult.

But what about the less-conflicted children of Woodstock? The beer-drinkers and hell-raisers, the clock-punching ham’n’eggers in dirty denim, living for the weekend? What was the colour of hoi polloi in the age of Aquarius? It was purple, brother. Deep Purple.

While they were never metal in the clinical, goathorns and hellfire sense, Deep Purple were always heavy, and got heavier along the way, carving out a path of sonic excess that would spawn the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal and its culture of headbanging true-believers.

If any one band was responsible for ushering in the era of long-haired, ear-shattering, spectacle-creating Rock Gods, it was Deep Purple. With early-career smashes like Highway Star, Speed King and Smoke On The Water – a song so ingrained upon rock culture that heavy metal kids can hum the signature riff in the womb – the band toured the world, pummelling audiences with thick slabs of groin thunder, establishing themselves as the preeminent emissaries of the new cosmic heavy.

However, as the 70s wore on, the trappings of success did their damage, and Deep Purple’s perfect rock’n’roll machine began to throw off Spinal Tap-esque sparks. Ego wars, revolving-door lineups, betrayals, bad records, lean-times, death and disease, all were hurled into Purple’s thorny path as the decades rushed past. And yet, half a lifetime later, they’ve endured, highway stars to the end.

“Think of it as a journey, an expedition,” says Ian Gillan, Deep Purple’s longest-running and best- known frontman. “We were going somewhere, and there was no map. We made it up as we went along.”

Gillan’s journey with Purple began in the summer of 1969. The band had already been together for a year, but after an initial brush with success, they were stalling out. Their debut album, Shades Of Deep Purple, was released in July 1968 and spawned a surprise American hit with their cover of Joe South’s Hush. Seizing the moment, they toured the US with Cream and rushed out a second album, the spacey Book Of Taliesyn.

While it sold respectfully in the US, it spawned no hits, so the band tried again with 1969’s self-titled Deep Purple. They marked their first foray into heavier sounds. Wrapped in a nightmarish Bosch cover, the airy acid- delica of ’68 was sloughed off in favour of tribal thumping and menacing riff-rock. Songs like Chasing Shadows and Bird Has Flown were stark stabs of proto-metal bludgeon. It was clear that the band had found their direction.

The album tanked, but the die was cast, and a rift developed within Purple’s ranks. Guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, drummer Ian Paice and keyboard player Jon Lord wanted to continue exploring the thick, fuzzy sounds of the new album; vocalist Rod Evans and bass player Nick Simper weren‘t so willing to embrace this new era of overkill. Within months, they were cast out into the wilderness. Simper went on to form Warhorse; Evans moved to the US and joined space-metal freaks Captain Beyond. As for Purple proper, around that time they happened to catch Ian Gillan’s pop-psyche band Episode Six, and suddenly the clouds parted. Gillan and Episode Six bassist Roger Glover were poached, and the hustle was on.

“We had some great musicians,” explains Paice, Purple’s only constant member, “so there was never any question about our musicianship. What we didn’t have were great songwriters, which is what we got with Ian and Roger.”

“I think my range was a bit more adventurous than Rod’s, let’s say,” says Gillan, “which is what they were looking for. They wanted to let loose.”

After a couple of odd distractions – Gillan was recruited to record the part of Jesus for the Jesus Christ Superstar album, and the whole band performed with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra – Purple’s revamped lineup hit the studio to record 1970’s In Rock. A watershed moment in heavy rock history, it spawned two classics: the raucous, ramshackle Speed King, and the throbbing 10-minute stoner epic Child In Time. The album eventually scraped the top five rock charts in the UK, secured Purple’s position as heavy rock pioneers and propelled them into a period of unparalleled productivity and success. But as Gillan explains, it certainly didn’t feel that way at the time.

“They didn’t want to know about us in England. We were playing in the same halls as we were with Episode Six. Nothing from the first three records, Hush or anything, interested anyone in England. But we knew we were on to something, so we kept at it.”

“It was a huge leap into another dimension, musically,” says Paice. “We had no idea if it’d be successful, but it was great fun to play.”

The next two years found Purple on a punishing schedule of relentless tours and frequent trips to the studio. Hot on the heels of In Rock came the proggy Fireball, their first record to hit the number one spot on the UK charts. Six months later, just in time for Xmas 1971, Machine Head hit the bins, cementing Purple’s status as the kings of 70s metal. The album opened with the furious Highway Star, still the ultimate road-dog anthem.

“We were very prolific,” Gillan says of their early days. “Music was oozing out of us. We used to write songs on our way to gigs, and perform them that night. Highway Star was one example. People wouldn’t believe it, but fortunately we had a few journalists on the bus. One of them asked, ‘How do you write the songs?’ and Ritchie started playing one note on his guitar, as a joke. And I started singing, as we drove down the highway. It wasn’t exactly the same as it was on the bus, but we performed it that night in Portsmouth. That happened a lot.”

Machine Head boasted Smoke On The Water, too, a song with perhaps the most recognisable riff of all time. It was based on an incident the band witnessed in Switzerland while they were recording in a mobile studio. Frank Zappa and the Mothers Of Invention were playing a gig at the Montreux Casino when an overzealous fan shot off a flare gun, starting a fire that burned the casino down to the ground. Purple watched the mayhem from the safety of their hotel, with Roger Glover noting how the smoke snaked across Lake Geneva. This oddball ode to accidental arson became Purple’s biggest hit, and shot Machine Head to the top of the rock charts all over the world.

“Smoke… was a seven-minute song. It never got played on any radio station, anywhere in the world, until someone at Warner Brothers thought they could do an edit. It didn’t do anything at all to the song, apart from make it worse,” chuckles Gillan. “The edit followed the rules of the radio, and it became a hit.”

1972 was another action-packed year for Deep Purple. After a particularly punishing gig at the London Rainbow Theater, Purple was recognised as the loudest band in the world by the Guinness Book Of World Records, an enviable honour for any hard rock band.

“The Who were probably louder,” admits Paice. “We were just the first to have meters to record our volume levels. Still, you needed something to stick out those days, and loud worked.”

In August, they released the double-live Made In Japan album. With seven songs spanning four sides, it illuminated the jammy aspects of Purple’s gigs, the flash of Blackmore’s guitar heroics, and the tribal cosmic funk of the band’s backline. More importantly, it revealed the global appeal of the band, and why their music resonated so deeply with so many people.

Purple weren’t sexy like Bowie or sinister like Sabbath; they didn’t require a cocktail of chemicals, a working knowledge of the Tolkien universe or protest signs to enjoy them. This was everyman’s hard rock, the weekend release valve for wage slaves, high school zeroes and pinball wizards. These were the people who covered their jackets in Purple badges, wore Purple t-shirts daily and grew their hair just as long as mum or the boss would allow. In years to come, they would spawn the modern diehard metal fan, he who tattoos ‘Slayer’ on his arm or spends half a year’s pay to see Kiss perform on a boat. But in ’72, they were simply Deep Purple fans, and they were legion.

“We’ve always been popular with working class people,” says Paice. “They always loved us in places like Detroit.”

But with success came its nasty trappings, and for Gillan, it was time to walk away. He finished another album with the band, 1973’s Who Do We Think We Are, but by the summer of ’72, he’d announced his departure from Purple.

“I was very sad and uninspired,” he says. “The music became formulaic. Also, everyone had girlfriends, and the chemistry changed. The girlfriends didn’t get along and they didn’t get along with management, and management wasn’t happy that we weren’t getting along. We travelled separately, ate separately and the only time we ever saw each other was when we were needed professionally. Once that’s broken, it’s broken. I thought I’d quit while I was ahead.”

For a time, Gillan gave up rock completely. “I dabbled in motorbikes, built a hotel. I never thought about being a singer ever again.”

The rest of Purple soldiered on, but the loss of Gillan proved a dizzying blow. Roger Glover left in 1974, replaced by former Trapeze bassist and singer Glenn Hughes. Future Whitesnake singer David Coverdale was drafted to fulfil frontman duties, and the new line-up went out to conquer America. They played the California Jam in April 1974, a rock fest that included Sabbath and boasted over 250,000 punters. It was also broadcast on US television, making Deep Purple a household name there overnight. No wonder, as their performance was explosive, in more ways than one.

“We had some histrionics, for sure,” recalls Paice. “We had an exploding Marshall cabinet that went a bit over the top. The roadies put too much gasoline in it, and it almost blew Ritchie off the stage. It blew my glasses off my face.”

The so-called Mark III version of band released two albums in 1974, Burn and Stormbringer. Both went gold in the US, with Burn cracking the Top 10. They sold equally well back home. Purple’s sound had changed significantly since Gillan’s departure, however, embracing the technical excess of prog and leaning heavy on Coverdale’s affection for soulful blues.

Blackmore, who had served asthe band’s musical director since its inception, had had enough. He left in ’75 to form Rainbow with Ronnie James Dio, leaving only Paice and Lord as original members. Blackmore was replaced by flamboyant American guitar-slinger Tommy Bolin, a relative unknown with a fluid, bluesy style. The new lineup recorded and released an extremely funky album, 1975’s Come Taste The Band. It sold poorly and, worse still, Bolin’s drug use fractured the band further.

“We had guys who needed help just getting on the stage,” remembers Paice. “It’s difficult keeping things together in those circumstances. Being in the band ceased to be fun."

Deep Purple called it quits at the end of a UK tour in March 1976. Tommy Bolin died of a heroin overdose a few months later. And that, for all intents and purposes, should have been the inglorious end of Deep Purple. But it wasn’t.

By the early 1980s, Ian Gillan had returned to rock’n’roll, fronting the Gillan Band. It was after a gig at London’s Hammersmith Odeon when inspiration struck.

“One of my heroes, a footballer named Rodney Marsh, came to the show. We went out for dinner afterward and he said, ‘Wow, what a show! Great band! Mind you, you’re not as good as Deep Purple.’ I said, ‘Yeah, you’re probably right.’ So he said, ‘Well, why the fuck don’t you get them back together again?’ If the greatest hero in your life said something like that to you… well, I figured I must at least try it.”

Gillan contacted Jon Lord, and the seeds for a reunion were sown. Gillan had something to attend before they could act on it, however…

“I got drunk with Tony [Iommi] and Geezer [Butler] and ended up joining Black Sabbath,” he laughs. They released the Born Again album in ’83 and toured the world with a Stonehenge stage prop. While successful, the whole affair was too awesome/ridiculous to last.

“The die was cast,” says Gillan. “After my year with Sabbath was up, I went back into Purple.”

Old wounds had healed nicely, and the classic line-up of Gillan, Blackmore, Lord, Paice, and Glover convened to write and record the excellent Perfect Strangers album in 1984.

“It was fantastic because everybody wanted it,” says Gillan. “But we were concerned… would it work? Would it have the same sense of adventure? After all, years had gone by. So we met in secret and had a rehearsal. It was obvious within 20 minutes of jamming that everything was gonna be fine.”

“It was a no-brainer for me,” says Paice. “I’ve worked with a lot of great bands in my career, but I’ve always come back to Deep Purple. Playing with Purple is like being home.”

Purple’s reunion was wildly successful. Perfect Strangers was a smash hit in the US and the UK. The band toured the world and released two more albums, 1987’s House Of Blue Light and 1988’s live Nobody’s Perfect. But Gillan and Blackmore found themselves at odds, and by 1989, dysfunction had set in.

“Things had gotten pretty bad on a personal relationship level between he and I,” says Gillan. “I think it came about quite simply because I said we should be touring more. I illustrated my point by banging my fist on the table, and that was it. Ritchie was being contradicted, publicly, and so he went back and said, ‘I can’t work with that guy anymore.’ Those were the words, I was told. So they had to make a choice, him or me. They chose him.”

Gillan was out again. He was replaced by former Rainbow vocalist Joe Lynn Turner, and this new line-up recorded one album, 1990’s Slaves & Masters. Fans and critics merely shrugged, considering it more of a minor Rainbow record than a Purple one. Meanwhile, the band was about to reach their 25th anniversary, and Purple’s core didn’t want to celebrate this landmark event without their (real) lead singer. After some ugly backdoor negotiations, Gillan rejoined the band as they recorded their new album, the ironically titled The Battle Rages On. The album, their 14th, was released in 1993. At this point, relationships within the band were so toxic that Ritchie quit on the eve of a Japanese tour.

“He tore up his Japanese visa,” Gillan recalls. “Very dramatic. So, we had to figure out what to do. We decided to continue on, and it became a thing of joy again. It became fun.”

Joe Satriani was recruited to help Purple finish their ’93-’94 tour schedule, but prior commitments made it impossible for him to join the band permanently. Former Dixie Dregs guitariist Steve Morse was signed on in 1994, and the band released Purpendicular a year later. There is a heady joy to the music of this album, which Gillan prescribes to the mood of the band at the time.

“It was fantastic. I could see the reemergence of Jon Lord and Roger Glover’s and Ian Paice’s personality, “ Gillan remembers. “It was as if a storm had passed, and the sun came out.”

There was one more significant line-up change: keyboard player Jon Lord retired in replaced by former Ozzy keyboardist Don Airey (Lord died in 2012) Purple has continued on, releasing a string of studio albums and steadily touring. Weathered and matured they may be, but four decades on, not much has changed. Styles shift and occasionally there’s a new voice in the choir, but Purple is still Purple after all these years.

“You don’t have to worry about egos anymore,” says Ian Paice. “Now all you have to worry about is remembering the songs.”

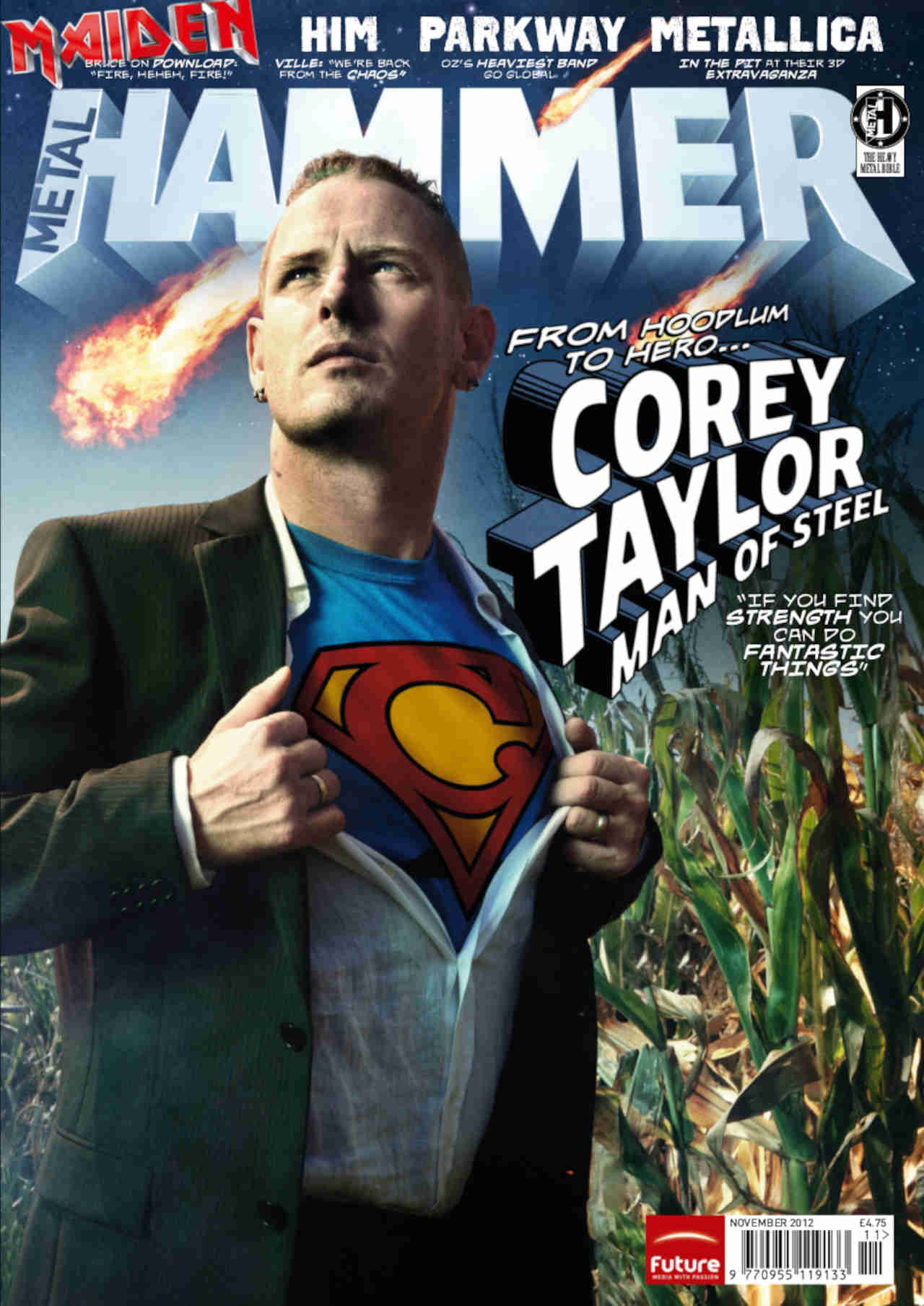

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 237, October 2012