When Elvis Presley summoned you, you came. It was August 1969, and the King

Of Rock’N’Roll was in the midst of a lucrative four-week run of shows at Vegas’ International Hotel, where he received a stream of awestruck visitors before and after his sets. No one said no to an audience with Elvis. No one except Ian Anderson.

“We were playing in Las Vegas around the time of the Stand Up record, and we were dragged by the scruff of the neck to some casino where he was appearing,” says Anderson, 50 years on. “I was never really a big Elvis fan but I suppose the first couple of songs that he ever recorded were part of my childhood fascination with music.“

Anderson wasn’t impressed with what he saw. “I was just appalled by the commerciality and the triteness of it all. And he was clearly out of his box. He was slurring his words, he didn’t know where he was, he would stop the band halfway through his song. It just wasn’t the way to see Elvis.”

But the King had heard that this hotshot new Limey band with the crazy hair and the flute were in the audience, and he wanted to meet them. Or at least that was the message Anderson got from the Elvis camp.

“They said, ‘Elvis would like to see you in his dressing room.’ I replied, ‘Tell Mr Elvis that it is a really great honour to have been here tonight, but we’ve got a show tomorrow, we’re a bit tired and we need an early night.’ And they said ‘No, you’re not listening – Elvis will see you backstage in the dressing room.’ I thought, ‘This is not this is not an invitation, it’s a fucking instruction.’”

Jethro Tull leader Ian Anderson is many things, but bulliable isn’t one of them. His heels were dug in so deep that not even the Memphis Mafia could strong-arm him into meeting the King in his court.

“I think a couple of bandmembers were miffed,” he says. “But I felt so embarrassed for him and I didn’t want to make things even worse. And obviously he would have had absolutely no idea who we were, no matter what they said.”

It was a typically Ian Anderson-ish reaction. He has built a career on confounding expectations, turning left rather than right, marching to no beat other than his own. It’s an approach has served him well during his band’s 50-plus year career. And never more so than on their second album, Stand Up: a transformative record and a key point in Jethro Tull’s half-century-long journey – one that marked the beginning of the band as we know them now.

We’re a long way from Las Vegas today. It’s a crisp winter morning, and Anderson and Prog are sitting in a lounge room in the grand Wiltshire pile that he and his wife, Shona, have called home for decades.

2019 doesn’t quite mark Tull’s 50th anniversary. The band formed in 1967 and their debut album, the blues rock-indebted This Was, followed in 1968. Anderson grudgingly marked the latter with an anniversary tour that began last year and extends into this. “I did think about hiding under the bed and not coming out for 12 months,” he groans.

But the fact remains that 2019 is a milestone year, if only because it marks the half-centenary of one of their most pivotal albums. Released in July 1969, Stand Up was a watershed for the band, one that put them in vanguard of the burgeoning progressive rock movement and turned them into ascendant stars in their own right.

In late 1968, Jethro Tull had seemingly little need to change anything. This Was had positioned them in the midst of the Brit-blues pack, alongside Savoy Brown, Chicken Shack and Fleetwood Mac. Titling their debut This Was was a sly indication on Anderson’s part that Jethro Tull had moved on from their initial sound before the album had even hit the shelves. The singer was already itching to broaden the band’s horizons.

“At that time I was going to see, at the Marquee Club, King Crimson, and the very first concerts by Yes,” says Anderson. “They gave me confidence that I could be more adventurous, at least if I had the musical chops to do it. Of course, I didn’t have the musical chops. I had to spend a bit more time learning to play a bit better and write songs that were a little bit more evolved.”

Anderson was writing songs for the follow-up that fitted his new brief before This Was had even come out. He ran through some of these ideas with guitarist Mick Abrahams, who was unimpressed.

“It wasn’t that he wasn’t interested and it wasn’t that he was incapable,” says Anderson. “It was just out of his comfort zone. Mick was a dyed-in-the-wool blues and R&B guy. He wanted to do more of the standard blues kind of thing. He wanted to make This Was Pt II.”

Anderson persuaded Abrahams to record a new song, Love Story, for a single. The track swapped earthy R&B for galloping folk rock. The B-side, A Christmas Song, was an even greater departure: a knockabout Yuletide ditty complete with mandolin, jingle and tart festive ambience, it was a marker of Abrahams’ disinterest that he didn’t even play on the latter.

“It was I who had to have the showdown with Mick,” says Anderson. “He got a bit puffed up and made some veiled threat. At which point I put down my flute and guitar and said, ‘Right, let’s have it out, man to man,’ knowing that Mick was a big bluffer and of course he would back down. Which was just as well, as he was twice my size.”

Fisticuffs averted, Abrahams left the room and the band. Jethro Tull might have lost their best musician, but they’d gained a future.

Love Story managed to sneak into the Top 30, justifying Anderson’s bold new vision, but there was still the matter of recruiting a new guitarist. One of these was Davy O’List, until recently a member of proto-prog trailblazers The Nice. Anderson was a fan and invited O’List to his North London bedsit to try a few ideas.

“We went through a few ideas and thoughts, but he was at least as odd a character as I probably appeared to him. We weren’t really making contact. He seemed to be very ethereal and weird and not really capable of a punchy conversation. I don’t think he was comfortable with me and vice versa.”

Slightly more successful was an unassuming young guitarist from Birmingham named Tony Iommi, who was a member of a heavy blues band named Earth. Anderson liked Iommi, and he seemed to be more broad-minded than Mick Abrahams.

“He was much more open to different ideas,” says Anderson, “I didn’t realise that he had lost the tips of several of his fingers in an industrial accident, and he did have a little physical difficulty in playing some of the things that I outlined to him. He had to simplify it in a way that might not have been a bad thing for some of the songs but it just wasn’t right for others.”

Iommi was briefly a member of Tull, long enough to appear in the Rolling Stones’ Rock And Roll Circus concert movie, where the band played their 1968 single A Song For Jeffrey and a new number, Fat Man. But by mid-December, he returned to Birmingham, and to his old band, Earth, who would soon change their name to Black Sabbath. “He did alright for himself, did Tony,” says Anderson warmly.

One guitarist who had auditioned at the same time as Iommi was Martin Barre, whose band Gethsemane had played with Tull at a gig in Portsmouth. Barre’s audition had been a disaster: his amp didn’t work properly and the guitarist was a bundle of nerves. Yet Anderson had spotted a glimmer of potential amid the technical and personal snafus. “I invited him back for a more private, less pressured little get together,” he says.

The pair crammed into the singer’s bedsit. Barre began playing once more, this time without an amplifier. Afterwards the two of them went for food at a greasy spoon café on nearby Highgate Road. “I seem to remember thinking, ‘He’s a good guy, he seems interested in a lot of the same sort of things as me and he’s probably about as unformed as a musician as I am, so we could sit down and learn together,’” says Anderson.

It helped that, temperamentally, Barre was a world away from his predecessor, Mick Abrahams. “Mick was a strong character, but he was terribly insecure,” says Anderson. “He would needle people, test them out. He was a tricky guy to be around. Martin wasn’t like that at all. He just wanted to be on his own most of

the time. His idea of rock’n’roll was retiring early with a sandwich and an Agatha Christie book, which wasn’t a million miles away from mine.”

By the time 1968 turned into 1969, Barre was the band’s new guitarist. The reimagining of Tull was underway.

If Barre was hoping for a gentle entry into the world of Tull, he was in for a shock. The first few months of 1969 were a whirlwind. In January, the band played a three-week UK tour, then flew to the US, where they’d spend the best part of the next three months, sharing stages with everyone from to Detroit firebrands the MC5 to Led Zeppelin.

“You knew that was a pretty racy lifestyle going on,” says Anderson of the latter. “At least in some parts of the band. Of course, there was quite clearly a difference between the behaviour of the rather remote and calm John Paul Jones and Jimmy Page, that boyish, smily, fun-loving guy who always wanted to share his photos with you. Photos usually involving soft fruit…”

It was in the US that Jethro Tull wrote and recorded the song that would become a key stepping stone in their transition from blues rock eccentrics into full-blown prog pioneers.

Anderson remembers being in a hotel somewhere in the Midwest when the band’s manager, Terry Ellis, collared him in the lobby and told him he needed to write a hit single. “So I said, ‘Right, so you want me to pop back to my hotel room and write a hit single?’ and he said, ‘Yes!’”

Challenge accepted, Anderson returned to his hotel room to knuckle down. Awkward bugger that he was, he opted to write it in 5/4 time – emphatically not the tempo hit singles are made of. Despite this deliberate cussedness, Living In The Past gave Tull their first proper hit single, reaching the Top 3 in June 1969.

By then, Jethro Tull had already begun recording Stand Up at Morgan Studios in North London. They had road-tested a handful of new songs on their US tour, among them Back To The Family, For A Thousand Mothers and the muscular A New Day Yesterday. They sounded little like anything Tull had recorded on This Was.

“I’ve always said that the biggest driving force behind prog rock is boredom,” Anderson says now. “That’s the thing that pushes people – they get bored with three chords or repetitive things, they go looking for something else. Your threshold can become quite low and you can end up feeling a little been-there-done-that. You do need to stretch out a bit.”

Jethro Tull certainly stretched out on Stand Up. The folk influence that had always buzzed away in the background was brought front and centre on Back To The Family, the gauzy Look Into The Sun shimmered with the faintest psychedelic haze, while Reasons For Waiting possessed what Anderson today describes as “something there that was evocative of a very quiet, more spiritual, almost church music. The kind of thing that I grew up with as a child in Edinburgh.”

Even more interesting were Bourée and Fat Man. The former was a playfully manic update of 18th- century composer Johann Sebastian Bach’s lute piece Bourée In E Minor, while the latter incorporated tabla-style rhythms and other world music flourishes of the kind popularised by The Beatles two years earlier on the Sgt Pepper track Within You Without You. Fat Man itself has been read as a dig at the departed Mick Abrahams.

“No, no,” insists Anderson, before changing course. “Well, actually it was perhaps a little bit of a jibe because Mick was self-conscious about his weight. He had a bit of puppy fat because he drank a lot of beer and was fond of a good pie. I came up with the idea when I was sharing a cabin with him on a ferry on the way back from a gig in Denmark. I’d bought a mandolin from a pawn shop. I had no idea how to tune it, and Mick was getting a bit annoyed with me just plucking strings. I jokingly titled it I Don’t Want To Be A Fat Man, which annoyed him even more, because he thought it was a jibe against him. Which it was and it wasn’t.”

Anderson is cagey about his other lyrical inspirations today. He firmly rejects the suggestion that We Used To Know – a Martin Barre showcase with tang of bittersweet nostalgia for “the bad old days” – stemmed from his own life. In fact, he shoots down the notion that any of his songs were autobiographical.

“Well, hardly any of my songs are actually about a given person or a given relationship,” he says. “Someone like Roy Harper would write some quite personal songs that were obviously born of personal experience in some deep emotional or even sexual moment. But I never wanted anybody to think I was writing a song just about them, because somehow that would seem like a betrayal.”

Still, he does concede that the inter-generational tensions he addresses on For A Thousand Mothers were partly influenced by his relationship with his own parents.

“I based that on my childhood experiences,” he says, “but it’s not just my childhood experiences, it’s everybody’s childhood experiences of growing up with parents who are telling them what they must do and what they mustn’t do. My parents will have listened to that song and they will have possibly wondered, ‘Did he really hate us so much he wrote this song about us?’”

The band finished recording Stand Up on May 1, 1969. Two days later, they were back on the road in the UK, before once again making another transatlantic crossing to embark on another lengthy Stateside tour.

Before they left, Jethro Tull played a show at Plymouth club Van Dike. It was an old stomping ground of theirs, and this time they were joined on the bill by Radio 1 DJ John Peel, a big supporter of the band during their early days.

“Afterwards, I said to John Peel, ‘Hi John, what do you think of the new songs?’” recalls Anderson. “He said, ‘I don’t like them. You should never have got rid of Mick Abrahams. You should have carried on doing what you were doing.’”

Anderson was crushed. “I thought he would like it because it had mandolins and balalaikas and weird shit going on. But he didn’t. It felt like a stab in the heart. And he never spoke to me ever again.”

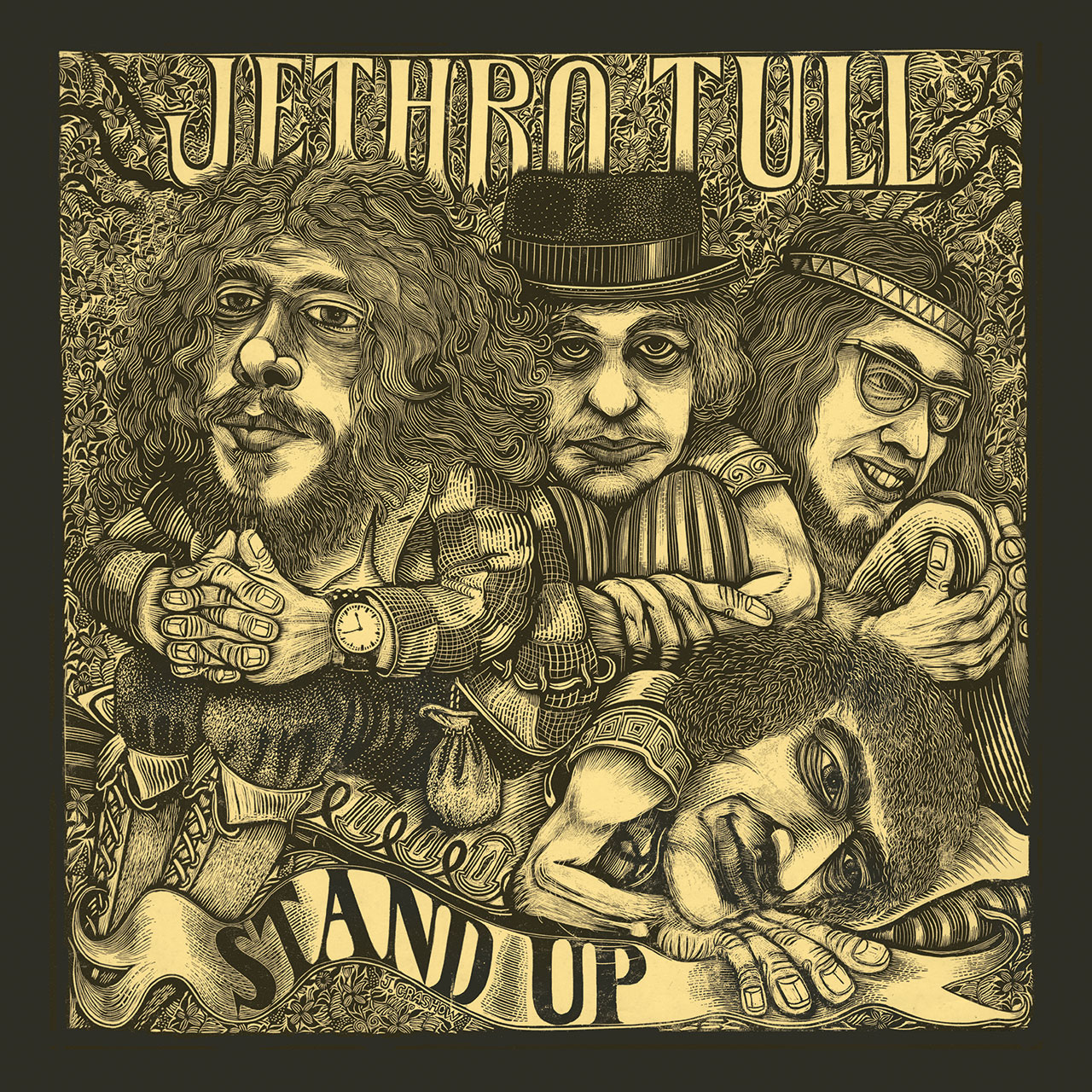

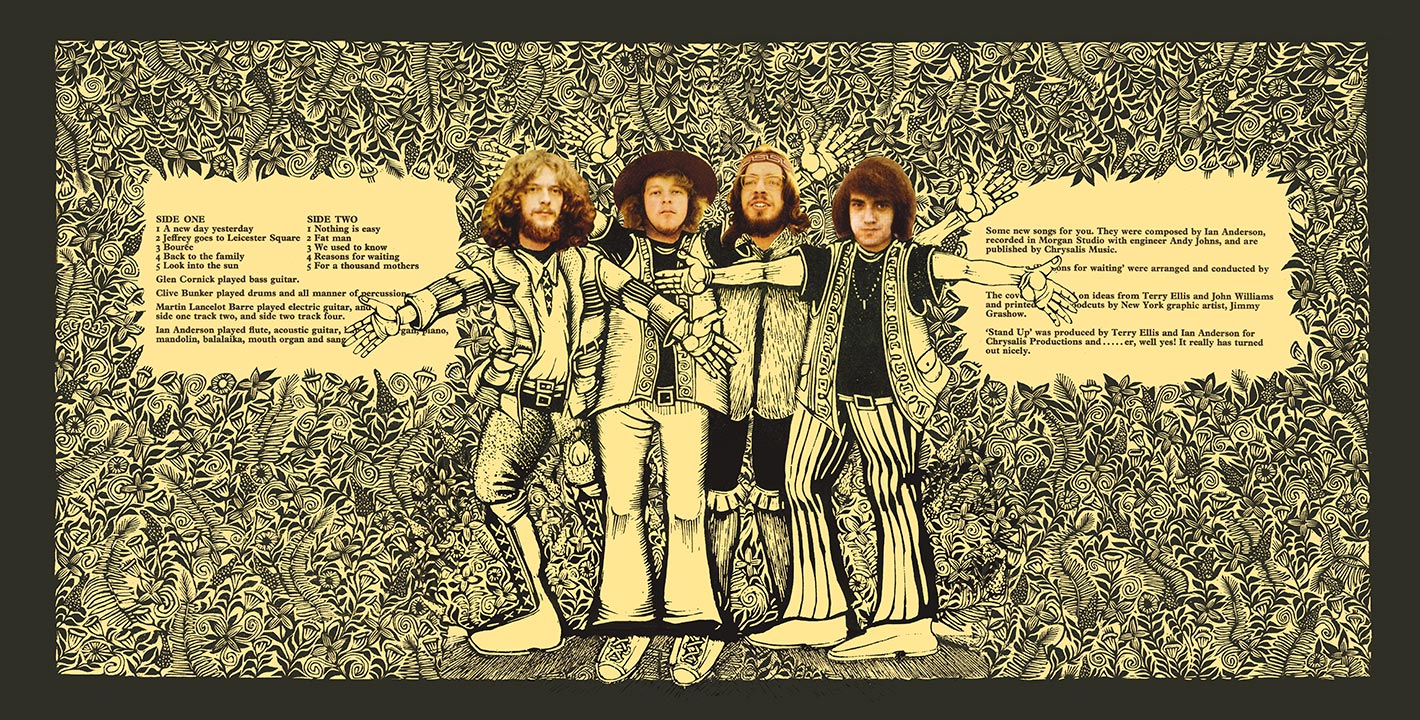

In the end, John Peel’s opinion didn’t matter. Stand Up was released in July 1969. It came housed in a striking gatefold sleeve featuring an intricate caricature of the band on the cover courtesy of American woodcut artist James Grashow and a 3D pop-up insert that saw the band literally living up to the album’s title.

Jethro Tull were in the US when they heard that Stand Up had reached No.1 back home. Anderson can’t recall exactly where, but he’s fairly sure that Joe Cocker was present.

“I remember having breakfast when Joe Cocker walked in and told me that Stand Up had gone to No.1 in the album charts. I said, ‘Oh wow. That’s nice. I don’t suppose you’re going to finish all that bacon are you, Joe? If you’re not going to eat it, could I have a bit?’”

This, too, is a typically Ian Anderson-ish reaction. There would be no celebratory party, not even the popping of a champagne cork, let alone anything more potent.

Even as a hairy 20-something, Anderson seemed out of step with his contemporaries: a young fogey in a tattered army greatcoat, a remote observer rather than an active participant. When the counterculture came knocking on his door, he hid behind the curtains and pretended he was out.

“I had very little relationship with all that,” he recalls today. “I remember going to clubs and everyone else being plastered, knocking back beers and brandies and whatever else. I didn’t drink, I certainly didn’t take drugs. I genuinely felt ruled out of that whole thing.”

He doesn’t sound regretful when he says this. Instead, he cites Jimi Hendrix as a cautionary tale against the more extreme aspects of the rock’n’roll lifestyle. The pair had crossed paths when Jethro Tull supported the guitarist in Stockholm earlier in 1969. “I only spoke to him once, while we were both smoking cigarettes in a corridor before a press conference that he didn’t want to do. He was having a little quiet, private time. He seemed like a man who was really uncomfortable with what he

was becoming.”

Six months later, Tull found themselves on the same bill as Hendrix at a big US festival. Things had changed. “He was surrounded by this phalanx of groupies-come-drug dealers-come-bodyguard-come-whatever. Harmful people. And we know how that turned out.”

What Anderson did share with Hendrix was a sense of showmanship. The first recorded instance of him attacking his flute while standing on one leg was at the Rock And Roll Circus at the end of 1968. But as the stages got bigger and his confidence grew, he began to inhabit the role of twitching, spinning, flute-handed wild man.

“The way it happens is that you get lost in the moment onstage, then you see photographs of yourself and read people talking about you. And you think: ‘OK, I’m getting noticed, so I’d better be that guy.’ You start to deconstruct the whole thing privately. You think, ‘What am I doing that makes people think I’m on amphetamines or just demented?’ And then suddenly you’re onstage in a codpiece and tights, playing the flute.’”

Contrived or not, it worked. Jethro Tull’s profile began to grow in the UK and the US – the latter assisted by a second stint supporting Led Zeppelin throughout the summer of 1969. Anderson could have been forgiven for allowing himself to sit back and think, ‘Job done’, but there was still a nagging fear that it might all be some kind of horrible accident.

“Did I think, ‘Blow me, we’re famous?” he says. “Yes. ‘Blow me, I’m famous in Melody Maker, but blow me, I’m certainly not famous and Italy, Spain, North America or anywhere else in the world.’ You might have had your first No.1 album but only in the UK. And it could also be your first and last No.1 album anywhere. You’re constantly reminded of all the one-hit wonders who have passed through town.”

Retrospectively, Stand Up has been viewed as the point at which Ian Anderson

assumed control of the band he had helped to found two years earlier. It’s a claim he doesn’t agree with – at least not quite.

“It wasn’t really a question of assuming control, it was a gentle transition really.

I suppose it was more of a democracy to begin with. But then there wasn’t

a busting amount to really discuss. There was no formal gathering to thrash out issues. I suppose as it progressed, there was probably more coming from me in terms of input than anybody else in the band. But it didn’t really get to be what you would call ‘control’ until probably 1974 or ’75.”

Benign dictatorship or not, the approach worked. Tull rounded out 1969 with wind in their sails – wind that would carry them through recording the follow-up, Benefit, and eventually onto Aqualung, the album that would elevate them to the superstar bracket.

But all that was in the future. After the necessary false start of This Was, Stand Up provided a significant marker in Jethro Tull’s long career. Today, Anderson looks back on it with fondness.

“I see it through slightly rosy spectacles, of course,” says Anderson. “But when people ask me what my favourite Jethro Tull album is, Stand Up will always be one of the two or three that I mention. The reason is that it’s the first album that I felt creatively responsible for. It was a first wet dream involving somebody else at the same time. It’s incorrect to say that we wouldn’t have carried on without it, but things could have been very different for us.”

This article originally appeared in issue 95 of Prog Magazine.