It’s August 3, 1983 and history is about to be made, in the shape of Prince's career-defining sixth album, Purple Rain. Inside the First Avenue club in Minneapolis, a sweaty congregation of 1,500-plus believers is staring across the low stage at an 18-year old guitarist named Wendy Melvoin, who’s making her debut with hometown heroes Prince & The Revolution.

Dressed in a sleeveless V-neck top, her curly hair tumbling over one eye, she strums a circular progression of gospel-like chords on her purple Rickenbacker guitar. It’s the final number in a 10-song set of new and wildly eclectic material. The other musicians fall in lightly behind her. The hypnotic groove swells for nearly five minutes, while the leader of the band, lurking in the shadows, wrenches some sustained fuzzed-out cries from his Telecaster.

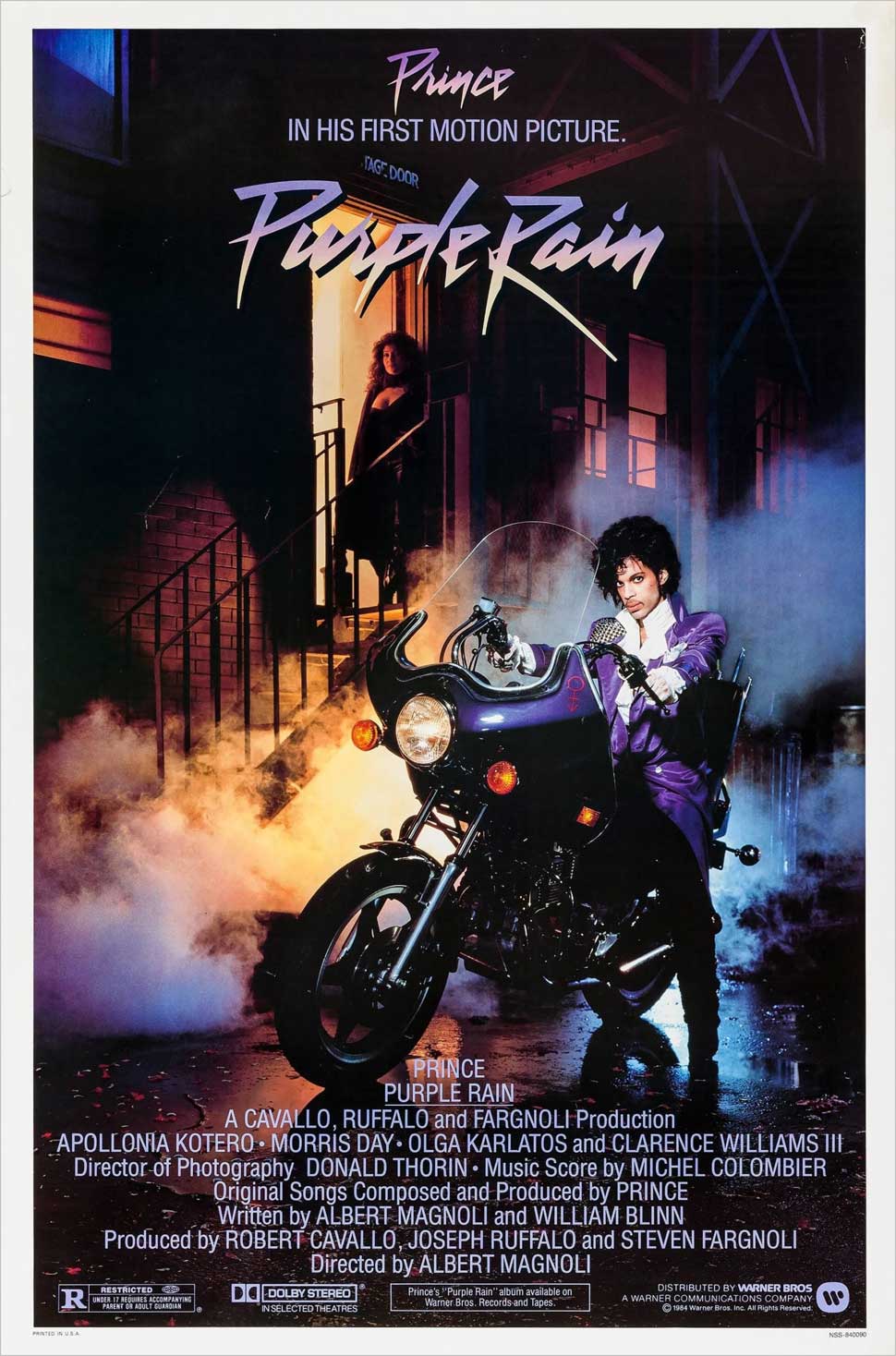

Finally, he flips the guitar behind his back, gunslinger-style, and steps to the microphone. Purple lamé jacket, ruffled collar, Little Richard hairdo, this magnetic five-foot-two soul preacher closes his eyes and sings, ‘I never meant to cause you any sorrow...’

There are no cheers of recognition. This is the debut performance of Purple Rain, the title song of the album – and movie – that will propel Prince Rogers Nelson into the pop culture stratosphere.

Within 18 months, the 25-year-old dynamo, who’s already charted with songs like Little Red Corvette and 1999, will be selling out arenas. He will also rival Bruce Springsteen, Madonna and, most significantly, Michael Jackson as the artist who defines the decade of the 1980s. And maybe more than any of these iconic contemporaries, Prince, with his inimitable songwriting, production-style and sexed-up ethos will imprint generations of artists to come, from George Michael to Justin Timberlake to Lady Gaga to Beyoncé.

Purple Rain, an album that spent a staggering 24 weeks at No.1 and has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide, remains not only Prince’s zeitgeist moment, but the most thrilling and cohesive artistic statement he ever made.

This is the story of how it happened.

Prince was not a team player. Like auteurs Stevie Wonder, Todd Rundgren and Paul McCartney before him, the Minneapolis multi-track whiz kid wrote, arranged, produced and played almost every instrument on his first five albums, from 1978-1982. The minimalist, pogo-funk sound of those early records, typified by songs like When You Were Mine, I Wanna Be Your Lover and I Feel For You, was charmingly offbeat and original. But it was also insular. Prince must have sensed that if he was going to punch that higher floor on the elevator to global supremacy, he needed to rock. And to rock, he needed a band.

“The reason I don’t use musicians a lot of the time had to do with the hours that I worked,” Prince told Rolling Stone in 1985. “I swear to God it’s not out of boldness when I say this, but there’s not a person around who can stay awake as long as I can. Music is what keeps me awake. There will be times when I’ve been working in the studio for twenty hours and I’ll be falling asleep in the chair, but I’ll still be able to tell the engineer what cut I want to make. I use engineers in shifts a lot of the time because when I start something, I like to go all the way through. There are very few musicians who will stay awake that long.”

While he had toured with various players early on, it wasn’t until the breakthrough success of 1982’s album 1999 that Prince surrounded himself with the formalised line-up of musicians that he considered his equals. In 1983, he added an ampersand and called them The Revolution.

To be a member of Prince’s band meant not only staying awake but living up to the boss’s sky-high standards. Hit-making R&B producer Jimmy Jam, who played in the first of Prince’s many side project bands, The Time, told me, “With Prince, it was about work ethic. And I mean work. We’d rehearse seven hours a day. He’d come to our rehearsals, then go to his own rehearsals, then he’d cut all night in the studio, and the next day, he’d show up at our rehearsal with some new song that he wrote. And it would be Little Red Corvette or something, and we’d be like, ‘Wow, that’s dope.’

"The other thing he’d do, he never wanted you to have a free hand. When I would be playing the keyboards, if my left wasn’t doing something, he’d say, ‘Find a part. Fatten it up. Your hand shouldn’t be idle.’ Then he would want you to sing a harmony note. Then it would turn into, ‘They’re hitting choreography out there, you guys need to hit it too.’ He was like a drill sergeant, but it taught you that you could be so much better than you think you can be, if you just apply yourself.”

At the time of the First Avenue gig, the drill sergeant’s platoon consisted of Matt ‘Doctor’ Fink on synth, Brown Mark on bass, Bobby ‘Z’ Rifkin on drums, Eric Leeds on sax, guitarist Wendy Melvoin and keyboardist Lisa Coleman. The band’s headquarters was a huge warehouse on Highway 7 in St. Louis Park, a suburb of Minneapolis. There Prince built the soundstage and recording studio that became the launching pad for all things Purple Rain (the room’s cavernous sound was put to especially effective use on Let’s Go Crazy).

As he started to assemble the songs for the album, he opened himself up to a free-flowing trade of ideas from his band members. This change in Prince’s approach to record-making would be mirrored in the plotline of the movie, as his character, The Kid, slowly lets his guard down to allow his bandmates to co-write and contribute.

“It was a very creative time,” Matt Fink told Pop Matters in 2009. “There was a lot of influence and input from band members towards what he was doing. He was always open to anybody trying to contribute creatively to the process of writing.”

While Fink acknowledges Prince’s “oodles of talent,” he says that part of the Purple One’s genius was recognising what gifts The Revolution brought to the table. “Take Computer Blue, for example,” Fink said. “We’d always warm up before rehearsals doing free-form improv rock-jazz jams, and someone would start a chord progression. On that day, I started playing that main bass groove which later became Computer Blue.

"So the band started grooving on it, and Prince started coming up with some stuff, then we recorded a rough version and he took it into the studio and just incorporated it all and made it fly that way. Wendy and Lisa did some of the stuff on it. Prince borrowed the bridge/portal section from his father [a jazz pianist], who had given him some music over the years to play around with. So the song was a real mixture of different people and influences.

“But Prince was the main lyricist and melody maker for all the songs,” Fink stressed. “And never took any lyrical content from people.”

If Prince was the enlightened despot in this new democracy, his most trusted advisors were Wendy and Lisa, two West Coasters who hailed from music royalty parentage. Both of their dads were top LA session cats in the 60s and members of the famed Wrecking Crew who played with everyone from Sinatra to The Beach Boys. From them, the girls inherited their chameleon-like ability to provide the perfect parts for any song, regardless of groove or style.

Prince said of them in 1985: “Wendy makes me seem all right in the eyes of people watching. She keeps a smile on her face. When I sneer, she smiles. It’s not premeditated, she just does it. It’s a good contrast. Lisa is like my sister. She’ll play what the average person won’t. She’ll press two notes with one finger so the chord is a lot larger, things like that. She’s more abstract. She’s into Joni Mitchell, too.”

“We were absolute musical equals in the sense that Prince respected us, and allowed us to contribute to the music without any interference,” Wendy told Mojo in 1997. “I think the secret to our working relationship was that we were very non-possessive about our ideas, as opposed to some other people that have worked with him. We didn’t hoard stuff, and were more than willing to give him what he needed. Men are very competitive, so if somebody came up with a melody line, they would want credit for it.”

The duo broadened Prince’s horizons by introducing him to modern classical composers like Stravinsky, Vaughan Williams, Scarlatti and Ravel (“Prince played Bolero all the time,” said Melvoin). And those nouveau sounds found their way into several songs. The jabbing string section that threads itself through Take Me With You’s driving riff was arranged by Lisa and her brother David, who plays the cello on the track. And When Doves Cry’s startling baroque keyboard climax was Coleman’s influence. “I think I influenced When Doves Cry to the extent that Prince was engaged in a healthy competition with us,” Lisa later said. “He was always thinking, ‘How can I kick their ass?’”

Prince definitely preferred female company in the studio. In addition to Wendy and Lisa, engineers Susan Rogers and Peggy McCreary handled the recording chores for Purple Rain, in Minneapolis and Los Angeles, respectively.

“Women have a very nurturing nature, and Prince thrives in that atmosphere,” Susan Rogers told Marc Weingarten. “He likes a studio atmosphere where people are flexible.”

Rogers’s flexibility was tested when she was hired by Prince to create a studio in the warehouse on Route 7. Usually, a boomy, echo-laden space is a nightmare for audio engineers, but this time, the live vibe was just what was needed to match the nightclub footage for the movie. Still, Rogers did her best to convert the big cement room into a functioning studio.

“I had been working for Crosby, Stills & Nash as a maintenance tech when I heard that Prince was looking for someone,” she said. “I jumped at the chance. He wanted me to remove his home console and put it in this warehouse, which seemed a little crazy, but we managed to make it work. I mean, nobody had really done that before. The first time I met Prince, after everything was set up, he asked me to set up a vocal mic so he could record. I had never professionally engineered in my life, but I really had no other choice. That’s how I began my engineering career.”

Other important women in the mix for Purple Rain were Wendy Melvoin’s twin sister Susannah, who became a muse to the smitten Prince (they dated briefly), drummer Sheila E (who became a star on her own, with Prince’s guidance) and of course the film’s leading lady, Patty ‘Apollonia’ Kotero. Apollonia had stepped in when the previous co-star Denise ‘Vanity’ Matthews quit the film. She’s a prime example of Prince’s Pygmalion-like ability to shape even the most lacklustre talent into gold.

If all of this musical creativity had been merely for another album release, it would’ve still been remarkable. But during the 1999 tour, Prince had carried around a big purple notebook with sketches, notes and ideas for a movie script. He made it clear to his label Warner Brothers that the new songs were to be for a soundtrack to a film in which he would star.

He gave them an ultimatum: If they couldn’t land him a major movie deal, he’d find another label that could. It wasn’t an easy sell. Yes, 1999 had moved three million copies and was still on the charts after ninety weeks. Sure, videos for Little Red Corvette and 1999 played regularly on MTV. But to most people in 1983, Prince was what you’d call Lady Di’s husband. Hollywood didn’t take him seriously as a bankable leading man. In the end, Warner Brothers A&R man Mo Ostin agreed to pony up the money for the untitled film project.

The first draft of the screenplay was written by William Blinn, best-known for his Emmy-winning TV movie Brian’s Song, and episodes of Starsky & Hutch. Blinn, who called Prince “a rock’n’roll crazy,” was frustrated with the lack of communication from the artist, but managed to hash out a semi-autobiographical script called Dreams, about a musician from a broken home who rises to stardom through the ranks of the Minneapolis club scene. “This picture was either going to be really big or fall right on its ass,” Blinn said.

Soon the screenplay fell to Albert Magnoli, a 30-year-old director who had only one acclaimed student short film to his credit. Magnoli reportedly wowed Prince with an off-the-cuff reshaping of Blinn’s script. He described the love triangle between a brooding lead, The Kid (Prince), and a comic one (Morris Day), with a beautiful ingenue (Apollonia) at the centre.

He outlined the tensions between the Kid and his band, and how he has to learn to be a team player. He then suggested having the Kid’s mum and dad, an interracial couple, fighting whenever the Kid came home. Prince told Magnoli, “I don’t get it. This is the first time I met you, and but you’ve told me more about what I’ve experienced than anybody in my life.”

Meanwhile, back in the warehouse, Prince raced around, lording over every aspect of the proceedings. Fink recalled, “We were basically in boot camp – a disciplined regimen of dance class, acting class, and band rehearsing throughout that whole summer for about three months straight leading up to the start of the filming process. Prince had an acting coach brought in, a dance instructor brought in. It was just day after day filled with all those elements. Prince just worked nonstop. He never slept.”

And in front of the camera, Prince was a natural. Always rehearsed and ready with his lines, he set a polished example for everyone on set. Whether he was riding his motorbike through the country, flirting with Apollonia or stuffing his rival Morris Day into a trash can, he had a presence that was both relaxed and full of mystique.

The six-week shoot wrapped just after Christmas. Though there was more than enough material recorded for the soundtrack, Prince felt like it was still missing the one song that would crystallise the movie’s theme of parental difficulties and tangled love affairs. The song that would bring the world under his groove.

On February 28, 1984 he attended the 26th Grammy Awards, only to watch his rival Michael Jackson walk away with most of the trophies. Prince was nominated for Best Pop Vocal and Best R&B Vocal, but lost both to Jacko.

Two days later, Prince entered Sunset Sound studio with a song buzzing in his head. He programmed a funky, popping beat on his Linn drum machine. Quickly moving to vocals, then bass, keyboards and some fiery Hendrix-like guitar, Prince threw down the tracks to When Doves Cry in a few hours. As he and Peggy McCreary listened to the playback, he muted the bass track from the mix, and realised it was exactly what the song needed.

It remains one of those landmark singles that sounds like nothing else before it. The stark arrangement. The Oedipal drama in the lyrics. The raw erotic charge in the vocal. When it was released on May 16, 1984, When Doves Cry turned radio on its ear, flying up the charts to become a number one on the pop, R&B and dance charts. Mission accomplished.

The Purple Rain soundtrack was conceived as a double album, with tracks from The Time and Apollonia 6. But during post-production, Prince decided to bump them off and make a single album instead. His manager said that it was a purely economic decision, in that they’d reach more people if the price was lower. But Prince probably realised that this career-making record would carry more weight if he was the sole artist.

A month before the movie opened, the soundtrack had already sold 2.5 million copies. Let’s Go Crazy was on its way to be the album’s second number one. After a premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre that was attended by everyone from Stevie Nicks to Eddie Murphy, the film had a huge opening weekend, grossing $7.7 million and replacing Ghostbusters as the top film in the US. Costing only $7 million to make, it eventually pulled in $68 million.

An exhausting tour would follow, with Prince & The Revolution recreating the funky magic of the film in more than 100 cities around the world. “I nearly had a nervous breakdown on the Purple Rain tour,” Prince said in 2012, “because it was the same every night. It’s work to play the same songs the same way for seventy shows. To me, it’s not work to learn lots of different songs so that the experience is fresh to us each night.”

And it’s that hunger to always move forward that led to an eventual falling-out with Revolution band members (the title song forecasted, ‘It’s such a shame our friendship had to end’), feuds with record labels, lawsuits, name changes, successive marriages and comebacks over the years. Through it all, there’s been a prolific rush of creativity and musical experimentation, right up to his latest incarnation, with all-female backing band 3rdEyeGirl.

In the end, perhaps the greatest gift of Purple Rain for Prince, beyond the stardom and the most enduring songs of his career, was simply that he found a way to belong to the music world at large. In the years after, he wrote and produced songs for The Bangles, Sheena Easton, Madonna, Chaka Khan and Stevie Nicks. Today that creative collaboration has continued with new artists such as Janelle Monae, Trombone Shorty and Zooey Deschanel.

In 1985, still in the heat of Purple Rain’s glow, Prince reflected on balancing roles as a band leader and bandmate. “I strive for perfection, and I’m a little bull-headed in my ways,” he said. “Then sometimes everybody in the band comes over, and we have very long talks. They’re few and far between, and I do a lot of the talking. Whenever we’re done, one of them will come up to me and say, ‘Take care of yourself. You know I really love you.’ I think they love me so much, and I love them so much, that if they came over all the time I wouldn’t be able to be to them what I am, and they wouldn’t be able to do for me as what they do. I think we all need our individual spaces, and when we come together with what we’ve concocted in our heads, it’s cool.”

A decade later, keyboardist Matt Fink said: “Fortunately for us, we were at first brought in as strictly sidemen, then allowed to be in on the creative process as well, which was really nice of him. He didn’t have to do that. He could’ve had his pick of just about any great sidemen that were around out in LA or New York. The reality is that this was his career, and we were just allowed to fortunately be along for the ride as his sidemen.”