By the time that dyed-in-the-wool bluesman Charlie Harper first witnessed punk rock in the flesh he was 32. Immediately moved to embrace the scene, he initially reinvented his R&B combo The Marauders as The Subversives before finally settling on the appropriately short and sharp epithet U.K. Subs.

Having made their vinyl debut (caught live at Covent Garden Brit-punk crucible The Roxy on New Year’s Eve 1977) the quartet enjoyed a rapid ascent. Though largely dismissed by the music press, they found an early champion in Radio 1’s John Peel, and widespread grass-roots support as they surfed punk’s second wave. A flurry of hits (Stranglehold, Tomorrow’s Girls, She’s Not There, Warhead) repeatedly took them to Top Of The Pops and mainstream infamy, before they dipped back beneath the radar to become international cult heroes. Latterly embraced (alongside Sham 69 and Cock Sparrer) as pioneers of street-punk, the U.K. Subs – in a number of incarnations, but always fronted by Charlie Harper – have never ceased gigging, racking up more than 200 shows a year for as close to four decades as doesn’t matter.

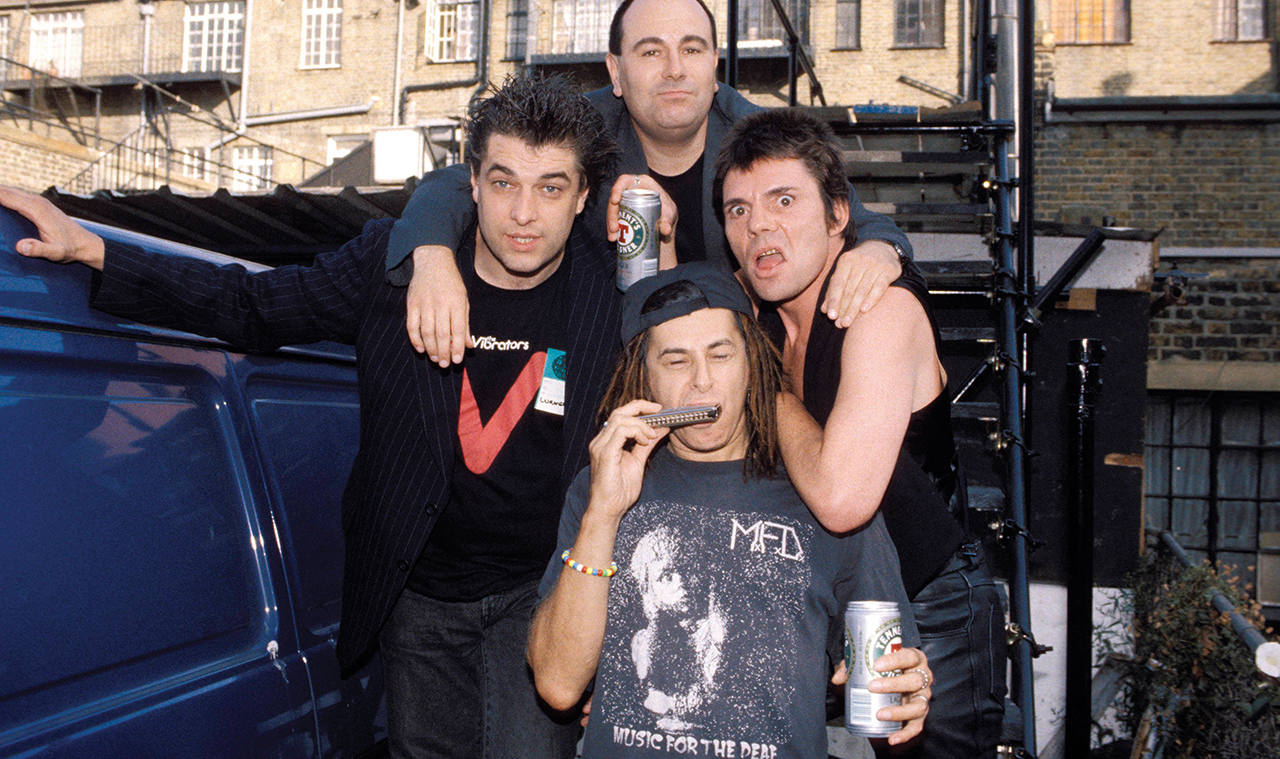

At 72, Harper has just delivered Ziezo, the 26th and final, alphabetically titled studio album from a very much in-form U.K. Subs.

So who exactly is Charlie Harper, and how did he come to be globally revered as the godfather of street-punk? His real name is David Perez, he comes from Hackney, and this is his story…

Where were you born and brought up, and when did you first engage with music?

I was born in London but moved to the Sussex countryside when I was eight years old. This was in the early fifties, when rock’n’roll had just started. I was a mad Elvis Presley fan, but I loved everyone from that rock’n’roll era: Bill Haley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, the Big Bopper, Buddy Holly.

What kind of formal education did you receive?

When I was in London I played truant a lot. Everyone worked but my grandma, so I’d go home, hang around the kitchen and taste her food. I was a bit anti-school, so I didn’t volunteer to do the exams to go to grammar school. I went to a radical secondary school where the pupils had school meetings and made their own rules. You were pretty much left to your own devices, but I got a great education. I was Chairman of the Young Farmers’ Club, so when it came to livestock, soil, trees, or any kind of agriculture my education was good. I worked on a combine harvester, stacking hay bales. It was a very different education to how it would have been if I’d continued living in London.

What did your family consider to be your prospects?

They wanted me to be a hairdresser, so I could do their hair for free. And that happened. I left school when I was fifteen and went straight into a hairdressing apprenticeship.

You would have been in your late teens at the time of the R&B boom in London. What effect did it have on you?

I immediately loved the Rolling Stones. Followed them everywhere, sometimes saw them three times a week. They’d be playing a residency at Ken Colyer’s Jazz Club in Leicester Square or R&B night at The 51 Club, then they’d be at Klook’s Kleek in West Hampstead or the Station Hotel, Richmond and little clubs around the outskirts of London. The 100 Club had R&B nights twice a week; The Kinks and the Pretty Things played every week, The Yardbirds normally warmed up for the Rolling Stones so I always used to get there early. All the bluesmen came over to the first Marquee Club, under a jeweller’s in Oxford Street, where Manfred Mann’s band would back them. This was when R&B took over. All the jazz clubs started to have more R&B nights.

Were you still an apprentice hairdresser at that point?

I’d left by then. I was a street singer, a busker. Rod Stewart was a busker at the same time, and Al Stewart – he shared the same patch as me, on Tottenham Court Road, and sometimes the same songs. Dylan was the new thing then, and we both used to do It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding). The money was good. I remember getting a fiver off of someone once, and a fiver back then would pay your week’s rent.

Why did you take the solo route rather than form a band?

Early on I fell in with a bunch of beatniks. We were playing the Woody Guthrie and Jack Elliott songbooks. Those guys taught me to play guitar and harmonica, so that’s what I did. When I was fourteen I got a guitar that cost eight quid which I paid off by instalments. It had Bert Weedon’s Play In A Day guitar book with it, so I learnt to play my three chords in twenty minutes and was off.

When did you first recognise popular music as a vehicle for protest, a catalyst of change?

That’s what it was, what we were about. Street singers took over from the cinema queue entertainers, the old guard who’d tap-dance, sing and play, then with Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan came the protest songs that we were into. The beatnik guys were slightly older than me, but the kids my age got into modern revolutionary jazz – Roland Kirk, Miles Davis, Charles Mingus – so revolutionary ideas were everywhere. Then, when Dylan came along, we all got busking. Afterwards we’d end up in the pub above Leicester Square station. One night there was a band playing upstairs. I looked at another busker I was with and said: “We can do this electric stuff.” So we did. And never looked back, really.

When did you first start writing your own songs?

I wrote my first at the end of sixty-nine. The chords weren’t hard but it was difficult to play and sing. I never quite caught it, my band didn’t like it, but another band took it. It went ‘Help me set the people free, You have the key to open the door.’ Very hippie.

Were you dressing mod sharp, or taking the beatnik route?

Our hair was a little bit longer than normal, just over our ears, but that was considered very long in those days. We didn’t purposefully go out to be scruffy, but when I came into the house my father wouldn’t let me sit in the armchair in my jeans. He thought they were filthy things.

Where were you when you turned twenty-one?

My folks were on holiday in Belgium and they seemed to have forgotten my birthday, so I threw a party for some of my beatnik friends. I lived in Vassall Road, Brixton, which made it difficult to get a job. Luckily I wasn’t seeking one. Most people around there worked in the Freeman’s Catalogue warehouse. I tried it for a while, didn’t really like it and left after a couple of weeks. I soon found that I was making enough money to live by busking, so I left home and moved into a bedsit. Things were happy then. I had all I needed to survive and spent most of my nights in pubs.

Did you tune in, turn on and drop out with the advent of psychedelia?

We basically remained how we were. I only ever did three acid trips, but we all got into Hendrix and Syd’s Pink Floyd. Their light shows were amazing. Everyone went out and got projectors, made light wheels and freaked out in their own homes.

At twenty-five, what compelled you to rekindle your association with scissors and a hairdryer?

I got married in 1970. My wife’s sister was a hairdresser. She’d just got a shop, needed staff and asked me. She offered me twenty pounds a week, which was pretty good so I took the job. I’d done my apprenticeship so I could already dye hair, and was at night school learning to cut, which I picked up pretty quickly.

- Anthrax's Scott Ian on the link between metal and geek culture

- Every Song On Aerosmith’s Toys In The Attic Ranked From Worst To Best

- Megadeth visit fan in hospital after he was stabbed at show

- Why Iron Maiden refused to mime on Top Of The Pops

The early seventies must have been a good time to be a hairdresser.

It was. When I came into it there was a guy called Teasy-Weasy who’d transform people’s heads in minutes. It was like a revolution in hairdressing when he came along. Then Vidal Sassoon arrived with a completely different style – no rollers, just blow-drying, another big revolution. Just after I started, Una Stubbs did an advert for Dairy Box. She had this short, sharp, sixties haircut, very punky. Every girl wanted this haircut, and I was the only person in the shop who could do it, so I learnt to cut hair pretty well pretty young.

Did you have good chair banter?

Oh yeah. You become a bit of a psychiatrist. Everyone tells you their woes and worries and you become quite good at reading human nature. It’s very satisfying and every client is different.

It was also quite arty. My shop was on Tooting Broadway. At first we’d play quieter stuff – JJ Cale, Leon Russell – then around about seventy-four we’d also play the Velvet Underground and Iggy Pop, a lot of American so-called punk before it came over here. By seventy-six we were one of the first shops offering leopard-skin print dye jobs.

Did you ever attempt to glam up, a lick of face paint during the Ziggy age?

We got really weird, yeah. The Ziggy thing was very big and those were really great times.

Meanwhile, you were still making music. Were The Marauders as musically aggressive as the name might suggest?

Not really. The guitarist would jump off stage and go around the back of the audience, tie them up in his guitar lead. I still don’t like my band using wireless, it’s too easy. I like the chaos of wires: tripping up, being unplugged. I let photographers come on stage because I love the chaos of it. It’s distracting if we’re playing bad.

At this point we’re in the midst of pub rock.

It was a great community. The big place was the Tally-Ho in Kentish Town, a lovely pub. Kilburn And The High Roads played there. I got pally with Nick Lowe, and remember telling him a couple of bands were moving on and he ought to get Brinsley Schwartz down there. He was worried they might be too pop. But they were a brilliant band, and ended up with a residency. Most of the bands just did covers, but the Kilburns pioneered doing original stuff and it soon became fashionable. We’d been doing Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley and obscure R&B, but when we started doing some of our own we’d hear more people leaving singing Stranglehold than Chuck Berry’s Promised Land.

So Stranglehold dated back to Marauders days?

Yeah, that was written very early on.

When did you first become aware of what became known as punk?

We were still playing R&B, and there was a little girl at the back – sometimes you’d catch her doing a little dance that was very different. We were into Bowie and dressed pretty wild, so we used to go to this lesbian club called Chaguaramas. There was no straight night, but Friday was band night, so they were a bit more lenient and let us in. We’d go down there most weeks. Then one week it had all changed and was called The Roxy. That was the realisation that this wasn’t just about one little girl at the back who danced weird, it was like, wow, this is happening.

When you first discovered punk did you feel compelled to ally yourself with the scene, or was there a bit of, “If this is the way it’s going, we’d better embrace it” when The Marauders metamorphosed into the Subs?

I’ve always liked raw music, and this was even more raw than R&B so I actually liked it. I was already thirty when this was happening and my band were all teenagers, so I said: “Look, you’ve got to come down to this place, because this is the future of rock’n’roll.” I realised what was going on, and I had to say to them: ‘Look, I’m an old blues man. I love this, but I play the blues.” Then they went to The Roxy and it changed their minds. They came back and changed my mind for me. They said: “We want to be a punk rock band.” And I thought, “Oh God, I’ll try me best.”

When you were recorded for the Farewell To The Roxy album on New Year’s Eve 1977 you were first on the bill, but by the album’s release in April you were its main selling point. What did you do so right?

It was just our energy. Everyone was talking about punk-rock energy, and we just went for it. Bands look phoney if they can’t dance to their own music, and we could dance to ours. If people wanted to see punk for real, that was us. We loved our music so much that we got mesmerised by it. When you’re on stage you’re naked, people can see through you and they can see if you’re fake. It’s like that to this day.

Suddenly the U.K. Subs are hot, things are moving fast and the band has got to be more than a hobby. Meanwhile, you’re thirty-three. What were your circumstances by this point? What responsibilities did you have?

Nothing, really. My marriage had split up when I was about twenty-nine so I was pretty free. I was thrown out of the marital home and went to live with a friend who’d just bought a house. After that I was living round people’s houses and squatting, but living quite comfortably because I wasn’t paying rent. So I was doing quite well. In the early seventies I’d been a bass player and had to buy gear. Now, as a singer, I really didn’t have to buy anything.

The first-wave punk scene and London music media being what it was, they got a bit sniffy about the Subs arriving a couple of months late to the party.

We didn’t take a lot of notice of that. I don’t tend to listen to negative people. We were just happy to have people for us, like John Peel. When Farewell To The Roxy came out he kept playing our tracks. So we called him to try to get on his show. He wanted to manage us, put money into us, but Nicky [Garratt, guitarist], being very independent, wouldn’t have it. We ended up taking John’s advice by going to Spaceward in Cambridge to do our first single, C.I.D. Which he then plugged. We were known globally because of the BBC.

You’ve never been press darlings, and the Subs’ legacy is invariably overlooked by punk documentary film makers. What’s the problem?

We weren’t glamorous enough. The Sex Pistols, The Clash and The Jam were very glamorous bands, whatever way you look at it. I’m not putting them down. The songs, and their musicianship and ideas when they were recording, were really spot-on.

How did your life change when Stranglehold put you on Top Of The Pops and gave you the first of seven successive hits?

It was fun. You go out on the road, jump into a cab and you’re on the radio. We were on The Sooty And Sweep Show. Sweep’s up really early in the morning pogoing on his bed to one of our songs.

Two years on, when the hits dried up did you think, “Okay, that’s that, then. Time to invest in a couple of salons”?

No. The end of the hits was our own doing. Instead of allowing management to pick the most commercial thing, because they’d invariably steered us on the right track, we spoiled it all by saying no, we want the best song on there. So we went on Top Of The Pops with Warhead, more or less a punk protest song with very strong anti-war sentiment. We didn’t do ourselves any harm. Instead of being a flash in the pan we earned ourselves longevity.

When you released Another Kind Of Blues had you already decided to name your albums alphabetically?

Yeah. My memory’s never been that good, so I thought it’d be easier to memorise the order albums came in. I was in five different bands the year before I got the Subs together, so I made a vow to myself to stick with this band. Whatever kind of music I’d done before with bands had become popular after I left – country rock, Velvet Underground-type stuff, jazz. I was in a full-on country band that did Irish stuff, once. I was a bass player then, so playing every kind of music gave me a good grounding. Not that I was a good bass player.

Did you ever imagine then that you’d make it to Ziezo?

Yeah. I was determined. I’d get sick, and think I’d better start taking it easy, but I was determined. And there’s probably as many unofficial albums as there are official.

You’ve always been very visible. For decades propping up the bar at Dingwalls or other venues, always available for a chat, you had a lot in common with Lemmy in that respect.

Yeah, he was a mate and fellow drinker. Although Lemmy’s ‘hello’ to you was to pull out a penknife from his top pocket, scoop out a load of coke and shove it up your nose on his penknife [laughs].

You never seem to tire of going the extra mile; you’re always at the merchandise stall signing stuff. Is that an integral part of who you are?

It’s something I learnt to appreciate a long time ago. When I was a fan of all the bluesmen coming over from the States, I saw most of them and they were all more than gracious. They’d give you their time, invite you into their dressing room. I never forgot how generous they were with their time. So I always hoped that I could be like that.

You’ve had two heart attacks, yet you regularly clock up two hundred gigs a year. That’s a significant danger to your health, surely?

The first heart attack was in 1977 and the second one was about ten years later. When we first started, our drummer was a bit of a maniac. He wanted to knock on the door of every management and record company. I was under a lot of stress, taking too much speed, and it wore me out. I’m pretty clean now. I don’t touch drugs, just drink a bit.

After these heart attacks didn’t doctors advise you to find an easier way to make a living?

No. I didn’t tell them I’d been taking drugs. But once I’d spent a few days in intensive care I was as right as rain. When I had my first heart attack I was quite pleased. I’d had pneumonia and lung collapses before and they’d stopped me playing for a while, so I thought, “Oh no, not that again.” So when I learnt I’d had a heart attack I almost jumped for joy. After the pain of the first couple of days it’s easier than having flu.

Do your kids ever tell you to cut down on the gigging?

No. When I’m in Europe playing six days a week it’s hard going, but I dedicate my whole time to that hour on stage. I’m pretty restive until then, so I get through it. I don’t find it tiring. It’s like exercising. Playing music is a physical and mental release that’s so good for you.”

All over the world you’ve been embraced as the godfather of street punk.

I’m not the godfather. That’s Lou Reed. I’m the grandfather. I’ve got six grandchildren, so I must be. When I’m abroad and people come up to me and say I’m a legend, I correct them and say, ‘It’s pronounced leg-end.’ Then the next guy comes along and says: “You’re a leg-end.” So I take it with a pinch of salt, a bit of fun.

Even during punk’s leanest years the Subs were always there to fly the flag and spread the gospel.

Yeah, I’ve always said to the guys that we’re like a gang of plumbers. Call us to do a gig, we’ll come out wherever it is. That’s the way we work. In the early days, when we wore camouflage stuff, we saw ourselves as the SAS of punk. We’d go where no one else would go. We’d even warm-up for Cock Sparrer.

How did Guns N’ Roses recording the U.K. Subs’ Down On The Farm effect your bank balance?

We knew it’d be big money, but also knew our publisher was ripping us off. So we went to court and got out of our contract. The court case cost twenty-seven grand and we got thirty grand from Guns N’ Roses. A nice big pay day. After court costs we ended up with a thousand pounds each, which was lovely.

How many former members of the U.K. Subs have there been now?

Someone did tell me that it could be as many as eighty. I don’t know if I can go along with that, but it’s possible. I’d probably put it at half that. I’ve never really kept track. I’m always in the pub and I’ve forgotten.

Is it really correct that Ziezo is to be the final U.K. Subs album?

Yeah. We always intended it that way. The alphabet’s over and that should be enough. There’s younger people coming to our concerts that are still catching up with the old stuff, and every time I go on YouTube I’m discovering new talent. Sometimes we play with guys from different eras of the band, and I have to go onto YouTube to re-learn old songs. Now we’ve got a new guitarist, a new set-list, and it’s hard work learning new material. I remember Judy Garland saying: “I don’t want to be learning any new songs. I’m forty, and my memory’s not what it was.” So I think I’ve got an excuse, being seventy-two.

Could you ever give up touring?

People say: “Don’t you get fed up with it?” And of course I do. There are times I want to leave, do something a bit different, more arty, test myself, but we’re booked up until the Christmas after next. It’s like a roundabout you can’t jump off, and sometimes… you just wanna cry [laughs].

Well, if the bookings keep coming, you have to honour them, haven’t you?

This is it. We’re the punk plumbers, and while there’s pipes to fix, we’ve gotta do it.