A tale of domestic terrorism, a BBC ban, and the end of Hawkwind's pop career

Hawkwind's single Urban Guerrilla was meant to propel them into the charts. Then the Angry Brigade showed up

The list of songs that have been banned by the BBC is as long as it is ridiculous. Since the British Broadcasting Service – the UK’s public broadcasting corporation – has been banning songs since the 1920s, the list is a long one; too long to reproduce here.

It’s a vast collection of music that runs the gamut from the tame innuendo of Cole Porter’s Love for Sale to The Prodigy’s patently offensive Smack My Bitch Up, with a whole bunch of seemingly-random material in between.

Songs concerning themselves with sex, violence, drugs and alcohol, the Devil, and war abound, but the reasons for banning the vast majority of this seemingly innocuous material are baffling. Fatboy Slim’s Fucking in Heaven? Okay. The Monster Mash? Really?

A whopping 67 songs were banned after the start of the first Gulf War. This sub-list also contains its fair share of head-scratchers (John Lennon’s Imagine?), but much of the material is more obvious, such as The Cure’s Killing an Arab or Edwin Starr’s War. But where were the charting singles and rock radio staples from the world of heavy rock?

Two singles by Status Quo are as loud as this list gets. War Pigs, helloooo?! Don’t AC/DC alone have 67 songs about firing guns, canons, and shooting things down in flames? Motorhead’s Bomber single entered the UK Top 40 in the winter of 1979; how did this escape the ban hammer?

As it happens, Lemmy actually was banned by Auntie Beeb, and it was a song about a bomber… but maybe not the one you think.

Space Rock pioneers Hawkwind hired Ian Kilmister, aka Lemmy, as their bass player, just after the release of their second album In Search of Space. During the year previous to Lemmy’s hire, Hawkwind had established themselves as the go-to band for free shows and benefit concerts, contributing performances to the early Glastonbury and free festivals movements.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

With Lemmy on board, the band also aligned themselves with several fringe political organisations, playing benefit concerts for the likes of the White Panthers and the Stoke Newington Eight.

The Stoke Newington Eight were members of the Angry Brigade, a far-left militant group responsible for a series of bomb attacks in England between 1970 and 1972. Using small bombs, they targeted banks, embassies, a BBC Broadcast van, and the homes of Conservative MPs. In total, police attributed 25 bombings to the Angry Brigade. The bombings mostly caused property damage; only one person was slightly injured. Eight people eventually stood trial for these bombings between May and December in 1972.

It was during the Angry Brigade trial that Hawkwind performed a benefit concert for The Eight. Right around that same time, the Hawks struck gold with their Silver Machine single, released on June 9th, 1972. The record rose to #3 on the UK singles chart that summer, giving the cosmic crew a bona fide smash hit. But their brief intersection with the Stoke Newington Eight would have significant repercussions when the band attempted to follow up the success of Silver Machine with a new single in the summer of ’73.

The song Urban Guerrilla, co-written by recent Hawkwind acquisition Bob Calvert and Hawkwind mainstay Dave Brock soon after the band’s brief intersection with the Stoke Newington Eight, was a strong contender.

Musically, it’s quite simple when compared to the average Hawkwind track; less prog and more ‘rock'n'roll in style and structure. This was likely one reason it was chosen as the follow-up single to Silver Machine. Although… the choice was a bold one, as new recruit Calvert’s lyric seems to directly support the Eight’s anarchist philosophies and methods:

I’m an urban guerrilla, I make bombs in my cellar

I’m a derelict dweller, I’m a potential killer

I’m a street fighting dancer, I’m a revolution romancer

I’m society’s cancer, I’m a two-tone panther

So let’s not talk of love and flowers

And things that don’t explode

You know we used up all of our magic powers

Trying to do it in the road

I’m a political bandit, and you don’t understand it

You took my dream and canned it, it is not the way I planned it

I’m society’s destructor, I’m a petrol bomb constructor

I’m a cosmic light conductor, I’m the people’s debt collector

So watch out Mr. Business Man Your empire’s about to blow

You know I think you had better listen, man In case you did not know

It was rare at this point in the band’s history that the band would declare their political philosophies directly, without the drug-fuelled sword and sorcery trappings. The surface layer of Hawkwind’s lyrics consisted of hippie-trippy fantasy or sci-fi themes, with an underlying expression of desire to overcome oppression; to be free.

From the simple don’t-let-the-man-bring-you-down of You Shouldn’t Do That to the gritty urban hopelessness of Lemmy’s Lost Johnny, Hawkwind’s worldview condemned mainstream culture and embraced escape, by any means necessary… including chemistry. The Psychedelic Warlords (Disappear in Smoke) (from 1974's Hall Of The Mountain Grill) basically says, ‘modern society sucks, so let’s do drugs’, which handily sums up the vast majority of Hawkwind’s lyrical canon.

Urban Guerrilla stood out in stark contrast to Hawkwind’s usual cosmology, and was quite plain in its messaging. Band manager Doug Smith said, “It was a major political statement.” Guerrilla summarised the harsh reality of Hawkwind's political position, the dark side of the counterculture, the come-down of the 70s after ‘peace and love’ had gotten the hippies nowhere.

“We definitely had a sense that we were part of a revolutionary movement” agreed Lemmy, “not some hippie-drippy never land, something much more immediate.”

Bob Calvert’s time as frontman and lyricist in Hawkwind was the band’s most successful era; also their most turbulent. Calvert suffered from bipolar disorder, which often caused friction within the band, and during one particularly acute cycle, Calvert was committed to a mental hospital under the UK’s Mental Health Act.

The people closest to him were likely not surprised at all by the content of his Guerrilla lyric.

Nik Turner: “Robert Calvert used to dress up as an urban guerrilla. He wore jackboots and combat clothing quite a lot, khaki stuff. His influences were probably people like Lawrence of Arabia. He was really into military uniforms. One nervous breakdown he was having, he dressed up as a soldier, marched for 25 miles and admitted himself to a loony bin.”

With the Stoke Newington Eight trial a year behind them, the band chose Urban Guerrilla as their next single. The song was backed with Brainbox Pollution from the Hawks’ Top Twenty album Doremi Faso Latido, and released in July of 1973, two months after Hawkwind’s live mindfuck Space Ritual hit the Top Ten.

This band was on a serious roll; a lot was riding on the band’s next move. And the gamble seemed to work: initial sales of Urban Guerrilla were strong, and the record seemed likely to enter the singles chart in the Top Forty. Then, suddenly…

18 August: Two fire bombs exploded at Harrods department store at Knightsbridge, London causing some serious damage. No one was hurt. ‘The Troubles’ had arrived in London earlier in the year; the IRA would ultimately be responsible for 36 bombs detonated in the city in 1973.

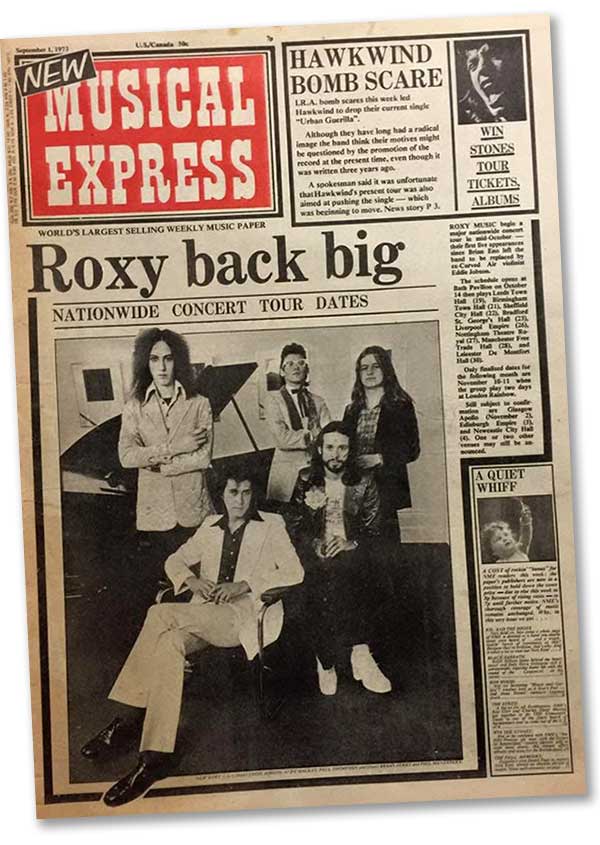

The August 18 bomb came just three weeks after Hawkwind’s new single hit, and forced the title and lyrics of the song into a new context. The BBC refused to play the record, banning it from the British airwaves. Band, management, and label also reacted quickly. A blurb in the weekly NME read:

"Hawkwind's new single Urban Guerrilla has been withdrawn from the market with immediate effect by United Artists, at the special request of the group themselves – despite the fact that the Hawks are currently undertaking a tour to promote the record, which is on the verge of chart entry. Reason for the withdrawal is the current spate of bombings in central London.

"A spokesman for the group commented; 'Although the record was selling very well, we didn’t want to feel that any sales might be gained by association with recent events – even though the song was written by Bob Calvert two years ago as a satirical comment, and was recorded three months ago.'

"At the group's suggestion, United Artists now plan to release the “B” side of Urban Guerrilla as a new single. It is Brainbox Pollution and will be out as soon as possible."

The promotion of Brainbox never happened. After three weeks in shops and on the air, the single had entered the charts at #39… but was instantly a non-issue. As BBC Radio is the only broadcast outlet The BBC in Britain, the ban had killed the record dead, and the withdrawal of the single was a necessary move by the band and their label to prevent accusations of opportunism as the IRA continued their bombing campaign in England.

Nik Turner related some of the fallout from the Guerrilla debacle in an interview for Hit Channel in 2012: “They tore the floorboards up in my house looking for guns and bombs and stuff like that. They didn’t find any of these things. Then, the record company withdrew the single because of unfavourable publicity and because of the situation in Ireland, really. The IRA was letting off bombs and stuff like that. So, the authorities investigated me and investigated the band.

"When we were on tour we were stopped by Customs, when we went out of Britain and we were kept waiting around for a day or so. It was very inconvenient, really. But the record company was withdrawing the record eventually, because the radio, BBC, wouldn’t play it anyway. They were very silly at the time and we had a lot of problems because of that single as you can imagine.”

The single’s withdrawal cost Hawkwind valuable momentum. They failed to follow up their #3 smash with another hit, and the band’s next two singles both failed to chart.

Who knows how high in the charts the Urban Guerrilla single would have climbed? Hawkwind’s albums continued to chart, and the band was well on its way to becoming a touring institution. But the banning of Urban Guerrilla killed any chances of Hawkwind ever becoming a ‘pop’ group, which was likely fine with linchpin Dave Brock, who famously pledged to “stay as far outside the music business as possible”.

Of course, some six years later, Lemmy would write a song about a very different kind of bomber, inspired by a Len Deighton novel of the same name. His post-Hawkwind band, Motorhead, would ride the song to #34 in the UK singles charts, five places higher than Urban Guerrilla had reached as it was pulled.

This feature originally appeared at Mayonoise.

Bob Mayo is not the Bob Mayo who played with Peter Frampton. But he was in Boston heavy metal band Wargasm from 1985 to 1995. They released three albums and one EP (all of which are now sadly out-of-print), had a video on MTV, toured Europe three times and select parts of the US twice, and had a great time doing it. He also recorded two albums under the fictitious band name Robot Monster Army.