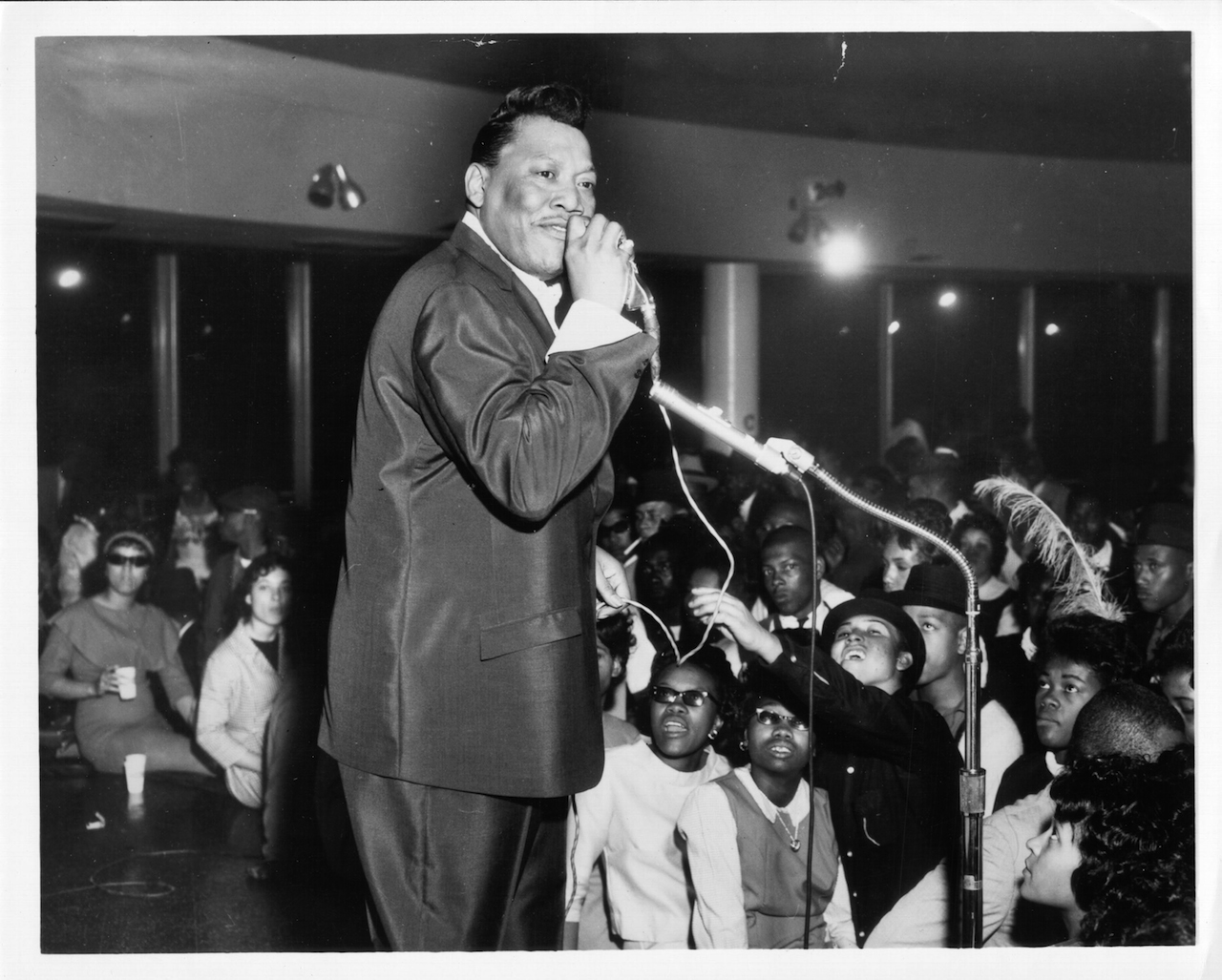

A Tribute To Bobby 'Blue' Bland

The last interview with a UK writer from one of the greatest voices in blues.

This article first appeared in The Blues Magazine #8, August 2013.

It’s a late 1930s summer afternoon in rural Shelby County, Tennessee. Across the Atlantic, war is brewing. But in the rural community of Rosemark, 25 miles from Memphis and the meandering Mississippi, the chief concern of a young farm boy is the soaring Fahrenheit out in the fields. Robert Calvin Brooks is growing up without the father who left the family home soon after he was born. His stepfather, Leroy Bridgeforth, also goes by the surname Bland, which young Robert will adopt. Not that he will ever learn how to write it, or read it.

Nearly three quarters of a century later, Bobby “Blue” Bland sits in his tour bus and remembers life on the farm. “I used to pick cotton,” he’s saying, in his gentle, gruff tones. “But I never liked it. I was about eight or nine, and it was just too hot out in the field, man. Boy, it was burning up. I knew there was something else better to do. I used to lay down where they had the high cotton, that’s the coolest place. Until one day, I lay down by a snake. That stopped me from that shit, I didn’t do that no more.”

I am sitting opposite him, gulping down neat rhythm and blues history from one of its true originals. The encounter took place less than three years ago, right after Bobby, already 81, had given an understandably low-octane but endearingly spirited performance at the Mississippi Delta Blues And Heritage Festival.

His passing on June 23 affords the opportunity to relive what became his last conversation with a British journalist, and very possibly his last interview at all, much of it unpublished until now. We’ve lost a man who invested soul music with 100-proof blues for 50 years on record, and even longer on stage. A man of quiet dignity who carved a life from an extraordinary vocal talent, and stayed true to his simple desire to entertain the public by singing the truth.

“He had exceptional delivery and understanding,” songwriter Dan Penn once said. “He made you understand what the song means to him. He didn’t just shuffle through. It’s blood and guts.”

Carry out a post-mortem on any of his very best recordings – and there are dozens of them – and you hear a style steeped not just in rhythm and blues, but in the country music and crooners in whom Bobby was immersed before he hit his teens.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“We didn’t have anything but country and western on the radio,” he told me. “That came out of WLAC, out of Nashville. I used to listen to the programme all the time, because I sang hillbilly anyway. I think they got more soul than most people give them credit for.

“It never crossed my mind to be an entertainer. I did spirituals. You had to be in church every Sunday, then you had bible study on Monday, and Thursday night was a prayer meeting at somebody’s house. You didn’t have the freedom, none of the stuff that these kids do now. Man, we wouldn’t even dare to have that run through our minds. We had no radio – when Joe Louis would fight, we had to go to somebody’s house and turn on the radio.”

There was no money to buy records, but Bobby was already singing, and getting paid for it. “I would sing on the weekend, country and western. During that time I’d go home with about $25, that was a lot of money, man, for about 10 years old. My mother said, ‘What you been doing?’ She thought I stole something. I said, ‘No, I’ve been working.’”

The blues got into his blood. “When I got a chance, I used to listen to it, but my mother and my grandmother didn’t like any of that blues, not in the house. I used to talk to this fella who played guitar. I stayed around older people and I never had much time for play, because I was serious about whatever I was doing.

“I used to try to be a mechanic. My old man was a mechanic, but it was a little too greasy, I didn’t like that particular work. My mother was a great singer, and my grandmother. I used to be with her in the kitchen while she was cooking, and she’d be singing some hymns, and they sounded so good. She could paint a picture with a hymn that you wouldn’t believe. That’s really where I got my gift, from listening to her and my mother.”

World War II was just over when Bobby, his mother Mary Lee and stepfather Leroy moved to Memphis. Using the name Robert Bland, the teenager sang in churches, in a gospel group called the Miniatures. A couple of years later, Bland joined the band of sax player Adolph “Billy” Green, in which fellow musicians included fabled, ill-fated vocalist Johnny Ace.

“I didn’t really get into blues until I got to Memphis,” he said. “I got that off Beale Street, and I started listening to Charles Brown, Big Joe Turner, ‘Big Boy’ [Arthur] Crudup… Walter Davis…‘Mr. Five By Five,’ Jimmy Rushing… and I enjoyed them.”

- BB King: the life of riley

- Albert Castiglia: "I don't take any shit, and I owe it all to Junior Wells."

- Unique Memphis Slim live record found in charity shop

- Buyer's Guide: T-Bone Walker

Bland and Ace were among the loose assembly of bluesmen known locally as the Beale Streeters, centered around that famous Memphis locale. Their number also included Bobby’s later running mate Junior Parker as well as Willie Nix, Roscoe Gordon, Earl Forrest, Phineas Newborn and an already-rising guitarist in his mid-20s by the name of BB King.

While Bland toiled to earn his rent, parking cars for Beale Street revelers and auditioning in Rufus Thomas’ talent shows at the Palace Theater, he and King would form a lifelong friendship from quite prosaic beginnings. “I used to drive for him,” Bobby told me. “He won’t own up to it, but he’d let me ride with him, and I used to catch his shows by being there with him. I knew all his music. BB had to get me away from his style, because that’s what I grew up on. I told him, ‘I can sing just like you,’ and he said, ‘Well, Bob, that’s good, but it won’t help you any.’ And I thought he was scared of me or whatever… he was telling me something for my own good.”

The friendship endured, extending to two splendid live albums in the mid-1970s. When BB turned 80 in 2005, Bobby was at his birthday party. “We’re just like that,” said Bland. “He’s one of the best people I’ve ever met, he did great things for me. The only thing B might not approve [me saying], he didn’t study anything but his music, [whereas] I do a variety. I listen to Tony Bennett, Perry Como, Andy Williams. Tony Bennett’s got one beautiful voice.”

Bland’s awareness of MOR craftsmanship would soon develop, and a spot on Thomas’ WDIA show, secured by local promoter Sunbeam Mitchell, helped raise Bobby’s profile. “I started with Rufus,” he said. “He had the amateur show there at the Palace Theatre. They had a prize, $5. That was big money.

“I used to sing Big Joe Turner, Charles Brown, Lowell Fulson, Amos Milburn. I did everything that was on the jukebox, because my mother had a restaurant, and whenever a new song was put on the box, I’d learn it, if it had any feeling. I did John Lee Hooker – I could never understand what he was saying, because he stuttered a lot, but he never did when he was singing. I won a lot of contests.”

Buoyed by that recognition, Bland went to cut sides for Sam Phillips at the Memphis Recording Studio, soon to become the famous home of Sun Records. The resulting 78rpm single, leased by Phillips to Chess, was released in 1951 and billed to Bobby Bland with Roscoe Gordon and his Orchestra. Gordon plays piano and sounds to be the vocalist on the poignantly-titled Letter From A Trench In Korea, but there’s no mistaking Bland’s bluesy wail on the flip, Crying. That release failed to shake much action, and late the same year, he was signed to Modern by Joe Bihari, one of the four brothers who had started the label in Los Angeles in the mid-1940s. Ike Turner arranged for Bland to record four tunes for Modern with his Kings of Rhythm line-up. But it was another false dawn, and one that was still leaving a nasty taste decades later.

“The Bihari brothers were the ones who told me to go back to the country and get a plough, that I’d never make a singer,” Bland said. “I was telling my mother about it, and she said, ‘What do they know about it?’ She made me feel good, because I’m an only child. She said, ‘I like your singing.’ I said, ‘Yeah, but you my momma.’ She said, ‘Somebody else likes your music too,’ because I used to sing at the cafe with the jukebox. As soon as they got to drinking, I used to be the runner to the liquor store on the corner, and I’d make 10 or 15 dollars, after they got drunk.”

In 1952, his confidence dented but not destroyed, Bland became an early signing by Don Robey, the Texas nightclub owner and president of Peacock Records, as the new head of the Duke label. His first Duke single, I.O.U. Blues and Lovin’ Blues, was just emerging as Bland was called up for army service. Lovin’ Blues grew into a bestseller in Memphis, Houston, Dallas and New Orleans, but Bland’s Uncle Sam years were not wasted.

He was in a Special Services unit, alongside Arthur Prysock, and polished his balladeering skills. “I would sing when I was in the service overseas, at the NCO Club, because that would get you out of detail,” he remembered. “They’d say, ‘Can anybody play an instrument, or sing?’ That’d keep you from doing KP [kitchen patrol].

“Nat ‘King’ Cole was the greatest singer I’ve ever heard. I had the chance to meet him a couple of times in California. What I like about him, his diction is so perfect [Bland pauses to break into Too Young]. I knew all Nat’s tunes, some of Billy Eckstine’s, and Roy Acuff and Eddy Arnold.”

Closer to the blues, those he admired included Charles Brown and Jimmy Witherspoon. Bland stayed in play even during his national service, not only recording on leave but marking the occasion with the wonderfully mournful single Army Blues. But after two and a half years, he was back in civvies by the spring of ’55, courtesy of his label owner.

“Don Robey sent me 13 dollars and 80 cents for the bus fare [to Houston, where Duke was based] when I got out of service. Mr. Robey got me a room at the Club Matinee – that’s where all the happening was – so I was in hog heaven. It was on KYOK and KCOH, when I first started hearing my records on the radio, and I thought I had arrived then.

“I got some little gigs, and worked Texas. I was with Junior Parker, I was his valet and driving for him, and I’d open up his shows. Then I got a little too good. Junior got a little bit jealous, and stopped giving me what he used to give me.

“So I told the band, ‘Well, fellas, I guess I’ll be trying to do something different.’ They said ‘Blue, where you going?’ I said, ‘I’m going to try to see what I can do.’ They said, ‘I’m with you.’ I said, ‘I ain’t got no money to pay nobody. You got a job, you’d better keep it.’ They said, ‘No, you gonna be alright.’

It’s My Life/Time Out, on Duke #141, became Bland’s first single that really travelled, breaking out of local hit status. A couple of records later, in 1957, he recorded his sixth post-army single, Further On Up The Road. To use Bobby’s word: “Bingo.”

Bolstered by superb horns and the muscular guitar of Duke session warhorse Pat Hare, the song went all the way to No.1 on Billboard’s R&B chart, succeeding Send For Me, by Bland’s great hero Nat Cole. Suddenly he had a flight path to glory: tough but tender vocals, sentiments that were lovelorn, lusty or rebellious, arrangements that were robust but with room for great subtlety.

Further On Up The Road was the first in a career total of 27 Top 10 R&B hits. Bland was set fair, even if he had to have a word or two with himself. “It gave me a big head, a little bit, people recognising me,” he revealed. “You don’t know how to control it because you’ve never had anything. All the stuff they were saying sounded good, and you forget who you are.

“So I got off track there, until [Duke business manager] Evelyn Johnson sat me down in her office and gave me a speech. [Revered record promoter] Dave Clark was the one that told me, ‘You ain’t made enough records to get cocky!’

“I didn’t like it, but it was the best thing that ever happened, because people can really fill your head with a lot of nonsense, and you’re weak enough to fall for it. It’s all painted, sugar coated, and it sounds so good.”

Married in 1958, Bland continued to tour with Parker despite their earlier disagreement, their joint Blues Consolidated package booked by Robey onto an average of 300 shows a year. 1961 brought Bobby’s first full-length album, the superb Two Steps From The Blues. “That was one of my best records,” he remembered. “I didn’t get a dime, but that whole LP was good, and that was a jumping off place for me. I had a good teacher, [Bland’s longtime Duke producer-arranger] Joe Scott. He told me to pay attention to the lyrics I was singing, to know what they mean. And he taught me to count, in my head, because I didn’t have no timing at all. I was always before, or with the beat, and he told me, ‘If you want to get across, sing behind the beat.’ I didn’t even know what he was talking about. He couldn’t sing at all, but he told me what I was supposed to do.”

Then there was the squall, the curious “throat-clear” technique that became Bland’s calling card. “If I don’t do that, then I haven’t been on stage,” he said. “I learned it from [Aretha’s father] the Reverend CL Franklin, my favourite preacher. The reason I did that was that I forgot a lyric. It dawned on me about a week later that by turning your head, you cut off one side of your vocal pipes. After listening to Franklin, I said ‘I might be on to something I could use.’”

Bland’s best showing in the pop market was 1964’s Ain’t Nothing You Can Do, which just made the top 20 on Billboard’s Hot 100. By the second half of the 60s, his star was descending, and as albums like The Soul Of The Man failed to find a big audience, drinking and depression played their part. But as he cleaned up his act, Bland couldn’t have known that his career still held two further dramatic upturns.

When Don Robey sold Duke to the ABC group, and Bland transferred to Dunhill, ABC and later the MCA label, Bobby found a new muse. ABC staff writer-producer and 1960s pop veteran Steve Barri oversaw a highly polished series of albums for Bland, beginning with the exceptional 1973 release His California Album.

“Steve Barri was very good, he wrote some good songs,” said Bland. “He liked the way I would tell a story, that’s how I became his favourite singer.” The following year, Bland’s first live album with King became a gold-selling success. The disco era was difficult, but Bland rose again when, in 1985, he was signed by the independent southern soul label Malaco, where he made a number of highly respectable late entries to his canon. “I grew up at Malaco,” he said. “It was one of the best things that happened to me.

“When I was with Duke, I was always uptight, because I didn’t have no breathing room. They didn’t give me the courtesy of the kind word to help me with what I needed, and I got it there.”

Malaco co-founder “Wolf” Stephenson recalled: “Luckily, we cut a few songs that were reminiscent of his old Duke things, and new things like Members Only, which reached his audience. At the time, I don’t think he had ever recorded with headphones.”

Bobby was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1992, and won a Lifetime Achievement Grammy five years later. His genuine love for his work and his audience kept him on the road until the recent illness that claimed him at 83.

“I’ll sing until I die,” he told me in that 2010 interview, before musing about his legacy. “I hope I come out on top, with somebody having an understanding about what I tried to do. I think we’ve left something here for them to go by.”

Prog Magazine contributor Paul Sexton is a London-based journalist, broadcaster and author who started writing for the national UK music press while still at school in 1977. He has written for all of the British quality press, most regularly for The Times and Sunday Times, as well as for Radio Times, Billboard, Music Week and many others. Sexton has made countless documentaries and shows for BBC Radio 2 and inflight programming for such airlines as Virgin Atlantic and Cathay Pacific. He contributes to Universal's uDiscoverMusic site and has compiled numerous sleeve notes for the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton and other major artists. He is the author of Prince: A Portrait of the Artist in Memories & Memorabilia and, in rare moments away from music, supports his local Sutton United FC and, inexplicably, Crewe Alexandra FC.