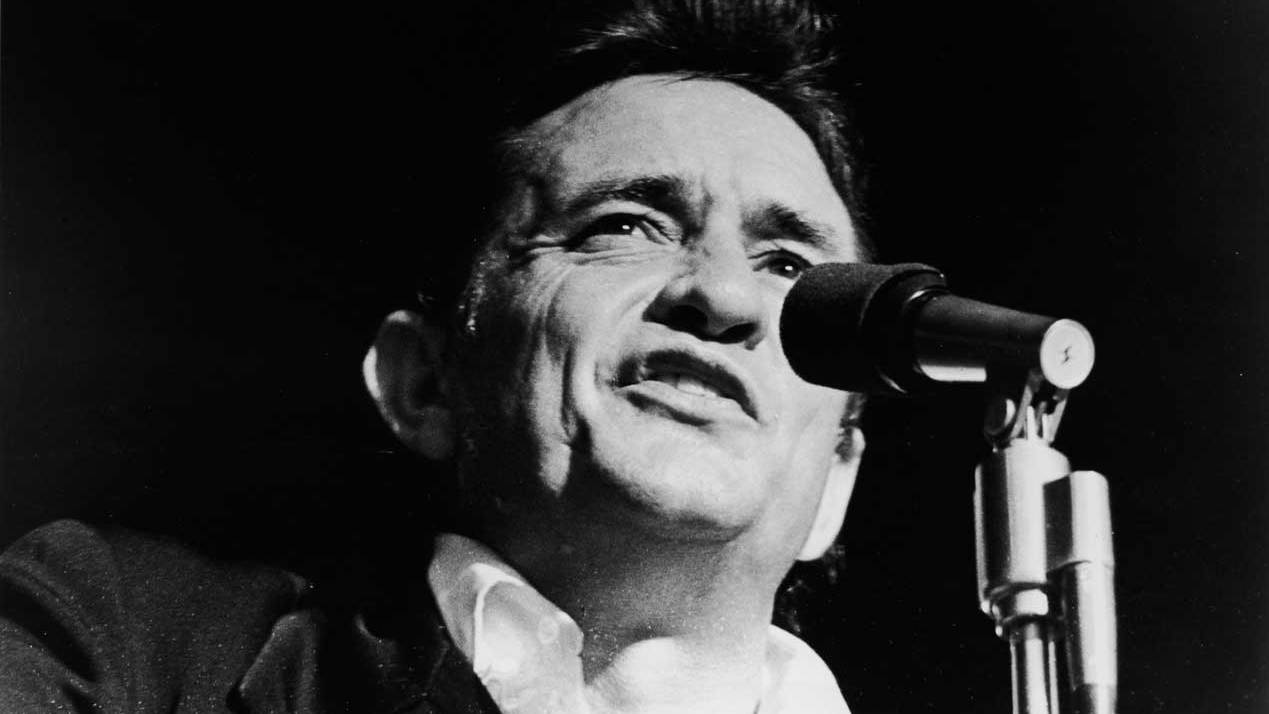

Johnny Cash died when he was 71, but he looked many years older.

Cash was one of country music’s greatest ever stars, but he always baulked at the definitions attached to him. He was a country singer who played gospel, rock‘n’roll, blues and folk. He was a wild drug fiend who nonetheless retained a deep Christian faith. He was a devoted family man who still had affairs. He came from a deeply conservative country cowboy background, yet was consistently outspoken in his support of the dispossessed and the downtrodden across all barriers, all races. Rubin was right. Only one label truly suited Johnny Cash. Outlaw.

The Biggest Sinner Of Them All

Cash once called himself “the biggest sinner of them all” and claimed he was “evil”, but he was deeply troubled by his own failings. Right from when he first started tasting success in the late 1950s, drink and drugs were a problem. Cash’s addiction to amphetamines and barbiturates – uppers to keep him going through the hardships of touring – was well known. He fought the problem for many years – “I tried every drug there was to try” – and entered rehab on three separate occasions.

His rebellious nature also got him into numerous scrapes with the law. Cash never served a prison sentence, but did wind up in jail on seven occasions for misdemeanours. The fact that he didn’t go down in 1965 when a narcotics team found him with a frankly ridiculous amount of prescription drugs (688 Dexedrine capsules and 475 Equanils, to be precise) suggests that Cash wasn’t just a drug addict, but a lucky man to boot.

The Man In Black

Cash started wearing black because it was easier to keep black clothes looking clean through the dust and the grime of long tours. Fellow country musicians – all rhinestones and loud shirts – teased him and called him The Undertaker. But he soon grew into the persona of The Man In Black. Yes, it was romantically outlaw. But it was way more than mere image. Cash wore black for the disenfranchised, the poor and the hungry. For those whom drugs had clawed apart. For those young men and women who had lost their lives in the Vietnam War. Cash didn’t sing counter-culture music, but those who had a mind to look found they could easily peer into his soul and see a kindred spirit.

Bob Dylan became a friend and they recorded music together. It might not have seemed like any kind of fit at all on the surface. But it was Cash, not Dylan, who said, “The old are still neglected, the poor are still poor, the young are still dying before their time, and we’re not making many moves to make things right.”

Cash met Presidents – some like Jimmy Carter became friends – but he was no political puppet. Richard Nixon tried to tell him what to sing at the White House in 1970. That went very badly. Just as it had for the TV execs who’d asked him to change the druggy lyrics to Kris Kristofferson’s Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down that he was singing on his own Johnny Cash Show.

“On a Sunday morning sidewalk/I’m wishin’, Lord, that I was stoned.”

- Caretaker to Acclaimed Songwriter: The Irresistible Rise of Kris Kristofferson

- Five Johnny Cash Covers That Should Embarrass Everyone Involved

- The 25 best country rock songs of all time

- Johnny Cash: the unplugged album that saved a country legend’s life

The Power Of Hurt

Johnny Cash’s stock fell between the mid-eighties and the early nineties. It was inevitable in some ways. This was a man who wasn’t built to chase either trends or approval. But his musical rejuvenation came from the unlikeliest source, when Irish stadium fillers U2 persuaded Cash to record a vocal for a song titled The Wanderer for their 1993 album, Zooropa.

In 1994, producer Rick Rubin saw how to put wind into Cash’s sails once more, by recording the man as naked as could be, in his living room and with just his guitar for support. But Rubin also found additional weight in unusual covers (Leonard Cohen’s Bird On A Wire) and specially commissioned songs from unexpected sources (Glenn Danzig’s Thirteen was just one). The public responded to Cash’s emotional depth, born out of wearying illness and the sense that the long road travelled had taken a heavy toll. The twilight of Cash’s life was bathed in respect and success.

His 87th and last studio album, 2002’s American IV: The Man Comes Around, featured a cover of Nine Inch Nails’ Hurt. Many see it as the defining moment of an outstanding career, an unflinching look at a strong, proud man coming to terms with decay and, ultimately, death. Devoid of any self-pity or sentimentality, Hurt is as powerful and unexpected a celebration of the outlaw spirit as it’s possible to find. And within a year of its release this giant of a man, this unimpeachable rock’n’roll rebel, was dead.

“To hear that Johnny was interested in doing my song was a defining moment for me,” said NIN’s Trent Reznor on being told the news. “To hear the result really reminded me how beautiful, touching and powerful music can be. The world has truly lost one of the greats.”

Years after his death, Johnny Cash’s casts a longer shadow than ever before.