Hawkwind started out with one clear musical aim: to create the sights, sounds and sensations of an acid trip, so that the audience could share the experience without the help of any drugs. In 2008, the band's official biographer Carol Clerk looked back on the early days of a successful mission.

Hawkwind were not shy of indulging in LSD. On the contrary, most of the band members were taking loads of it, and those who weren’t quickly left.

After one unexpected hallucinogenic adventure, original bass player John Harrison disappeared off the face of the Earth, or at least to America, never to be seen again. He has still to collect the tens of thousands of pounds in royalties that have been gathering interest for him in a special bank account for the last 38 years [Harrison died in 2012].

Guitarist Huw Lloyd-Langton’s experience of being spiked was even more dramatic. He became engulfed by all the horrors of a terrible trip on stage at the 1970 Isle Of Wight Festival, and subsequently suffered a complete nervous breakdown. Unlike Harrison, however, Huw would be brave enough to return to the mothership some years later.

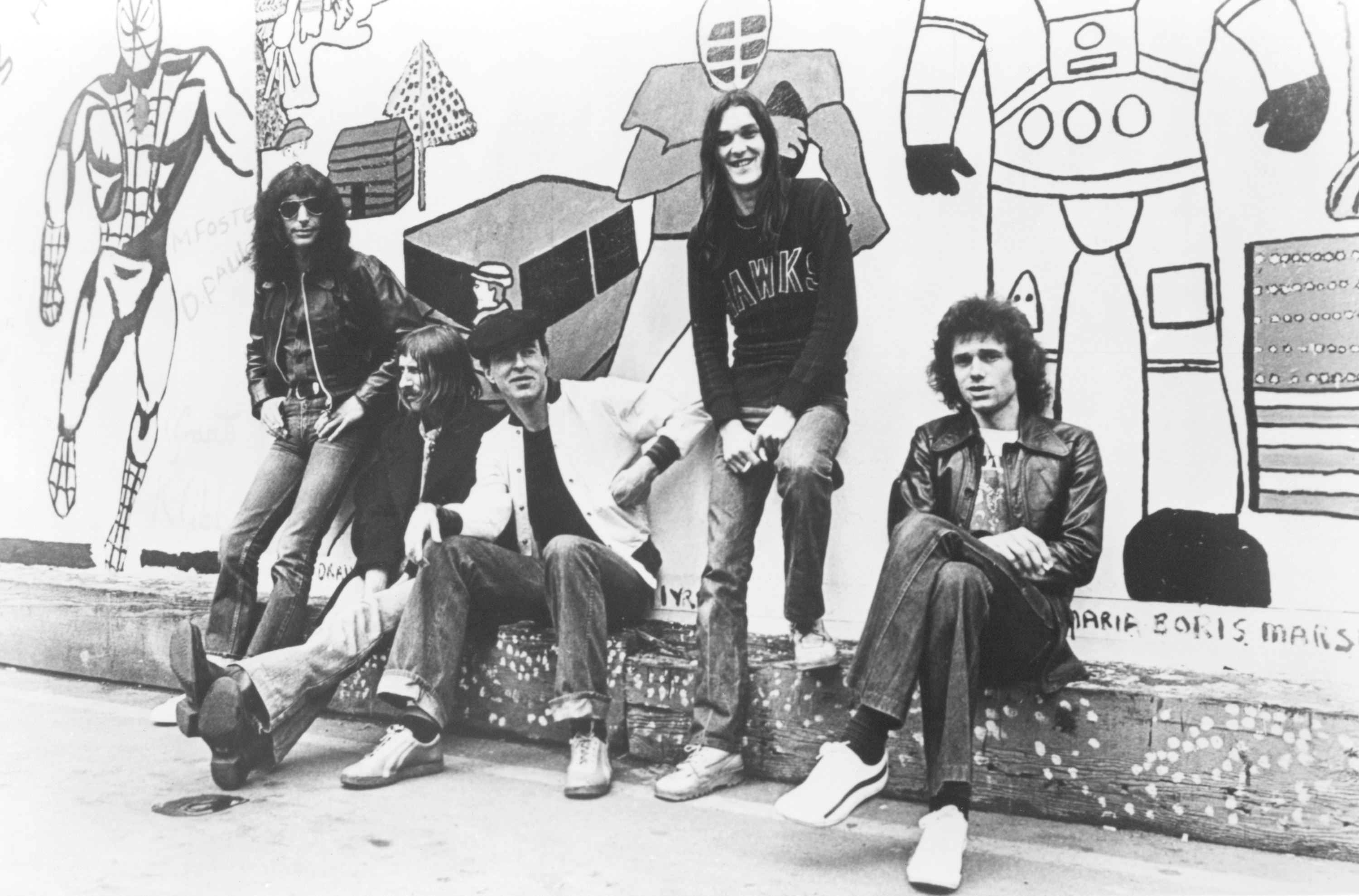

The story of Hawkwind began with Dave Brock (vocals and guitar) and Mick Slattery (lead guitar). Dave and Mick were busking companions in the mid-60s, going on to form a number of informal groups that played in blues and folk clubs around London. In 1967, both were exhilarated by the new psychedelia. With Brock recruiting Slattery to the second incarnation of his band

The Famous Cure, they set off on a tour of Holland with Tent 67, a psychedelic rock circus that travelled from town to town with a huge tent. The Famous Cure played lengthy blues jams with as many strange effects as Dave and Mick could coax out of their guitars. Returning to London, they hoped to set up a band that would explore psychedelia by fusing long improvisations with electronic music.

This was not virgin territory for either player. Brock had learned to make tape loops during a brief period of employment as an assistant film editor at a studio producing cartoons and TV ads. He went on to spend hours in his Putney flat, making weird and wonderful sounds with his guitar, an echo unit and a tape machine.

“There was a lot of bands doing weird stuff,” says Brock. “I used to fiddle around with tape loops. Mick Slattery used to come round to Putney and we used to plonk around there.”

At the same time, Brock was aware that psychedelia wasn’t just about the music: it was about a multi-sensory experience and, in the wider context, about an alternative lifestyle.

He remembers: “I used to go down to Middle Earth, the UFO and these clubs in the 60s, and we used to take LSD and jump around wearing our brightly coloured clothes. People could dance around like gazelles if they wanted to. It was freedom of expression. You’d go into Middle Earth and it would smell of incense and it would have smoke machines and lights flashing. It created an environment. That’s what people wanted then, these wonderful environments where you could jump around and bands would play long pieces of music. The Arts Lab had arty films and the old light shows with blobs flashing up on the screen. These were the beginnings of psychedelia in England.

“Our bright clothes were against the traditional nine-to-five of greyness and drabness and suits and bowler hats. Wearing bright colours, letting your hair grow long, was to be totally different – the psychedelic revolution! There was this wonderful, magical free spirit. People were trying to say: ‘We want to change things here.’”

The music was the soundtrack to a counterculture that embraced all kinds of creative individuals, including poets, artists, writers, clothes and lighting designers, photographers, silk-screen printers and market traders. News was exchanged, gigs advertised and crusades mounted through the pages of the underground press. Publications such as IT and Frendz would lambast drug squads and censorship while boldly campaigning for feminism, gay liberation, animal rights, CND, environmental awareness and the legalisation of cannabis.

“Notting Hill Gate was a real hotbed of revolution,” says Brock. “We’d hang out there and meet all these people. It was quite a close-knit circle. A community.”

However, it was not in Notting Hill’s hippie enclaves of Portobello Road and Ladbroke Grove, but in the Tottenham Court Road subway where Hawkwind began. Brock was busking when he struck up a conversation with bass player John Harrison, ex of the Joe Loss Band, and soon snapped him up for the new group. Drummer Terry Ollis, who’d previously only played informally with friends, was recruited through a classified ad in Melody Maker.

Brock, Slattery, Harrison and Ollis immediately began rehearsing in earnest. The sessions consisted of “long solos with echoes and repetitive rhythm patterns”, according to Brock.

Occasionally, their two roadies would join in for a jam. One was Dik Mik, an old pal of Brock and Slattery, who’d drummed in an early line-up of The Yardbirds. Now he had moved from the drumstool and was creating extraordinary sound effects using an audio generator and an echo unit.

“He wasn’t randomly making lots of noises,” says Dave. “He used to try to play the notes that we’d be playing.”

Dik Mik’s friend and fellow roadie was Nik Turner, an itinerant musician steeped in traditional and avant-garde jazz. Turner, a roustabout on the Tent 67 tour of Holland, contributed by blowing chaotic, free-form saxophone.

“Nik couldn’t play it properly,” adds Brock. “But he had his echo unit, you’d get all these notes flying around and it was really fast, so it worked with what we were doing.”

Turner and Dik Mik added new and exciting dimensions to the sound, and it wasn’t long before the roadies joined the band. They made their first appearance, as a six-piece called Group X, at All Saints Hall, Notting Hill, in August 1969.

It wasn’t so much a gig as a wild and cacophonous 15-minute jam, but it was enough to secure the instant approval of DJ John Peel – and a management deal. A record contract with Liberty quickly followed, by which time Group X had briefly become Hawkwind Zoo and then finally, just Hawkwind.

Incredibly, just when everything was coming together so perfectly, Mick Slattery walked out, mainly because he fancied a trip to Morocco.

Once again fate lent a helping hand in the Tottenham Court Road subway, where Dave Brock happened to bump into the talented young guitarist Huw Lloyd-Langton. Huw had previously worked in a West End music shop, and had met Dave there. Now he was at a loose end, after a year touring European army bases as a backing musician, and was only too pleased to accept Brock’s offer of a jam. It was, in fact, an audition for Hawkwind. Lloyd-Langton passed the test with flying colours and joined the band.

“Initially, the purpose of the exercise was to create a situation that would be a trip in itself without partaking of any substances, with lights and psychedelic sounds,” explains Huw.

“The idea was for people to get spaced out,” adds Brock. “The sound frequencies – high-frequency sound and low rumbles – affect your body and, in fact, your brain. So without taking drugs, you’d become disorientated and you’d become involved in the light show and the whole experience.”

The result was very effective. On one memorable occasion this perhaps worked too well, as Dave fondly recalls. “We played some university, I can’t remember which one, where everybody in the audience got pissed and a lot of people were really sick. You’ve been drinking beer and you’ve got a giant strobe flashing on and off and weird sounds going on – that’s going to make you ill. We got banned from that university.”

In these early, impoverished days of Hawkwind, a strobe was all they could afford in the way of lights, but it certainly made its presence felt, and not just on the spectators.

“I do recall the strobe bashing my flipping brains in,” admits Huw.

“We just switched it on and it used to make all our gear go, ‘click, click, click’,” chuckles Brock. “When we were playing a fast number, you were able to hear all this slow clicking going on.”

Hawkwind gigged relentlessly, sleeping in their old van unless a students’ union they played at was kind enough to offer to put them up on campus. The van – dubbed ‘The Yellow Wart’ – was already being used as a convenient crash pad in London by various members of the band who found themselves without somewhere to lay their heads. This didn’t usually include Nik Turner, however, as although he was homeless, he had figured out a complicated itinerary of squats and flats where he was welcome to doss down on the floor.

“The van was a complete tip… terrible-smelling socks,” says Lloyd-Langton, bluntly.

“Behind the seats was enough room for several people to lay next to each other in their sleeping bags, like the seven dwarves,” elaborates Brock. “Occasionally Dik Mik would sleep on top of the gear, only about two feet away from the top of the roof.

“We also used to do quite a few gigs on flat-back lorries in Notting Hill Gate and Wormwood Scrubs Common, and in 1970 at the Bath Festival with The Pink Fairies. All our gear got covered in dust and the guitars went out of tune with the generator going up and down. None of these things were romantic. It was quite a hard old lifestyle. But we were working a lot.”

Hawkwind went around the length and breadth of Britain, playing in every student hall and small venue that would have them. But in keeping with the spirit of the age, they also performed a vast number of free concerts and benefit gigs for the causes espoused by the counterculture, distributing flyers and copies of alternative newspapers to their audiences.

“I don’t recall ever being paid in those days, but I didn’t care,” remembers Huw. “All I was concerned about was getting up and playing for the love of it. Just so long as we had enough petrol to get to the next gig…” And of course, there was always LSD.

“We all used to take acid together,” asserts Brock. “It was a good drug to take, within reason. It made you question things a bit more. It’s helped so many artists, writers and musicians by supposedly ‘opening the doors of perception’. Yeah, it does make some people go haywire, but you have to be in the right mood to actually enjoy it. And you have to make sure you have somebody there to keep an eye on things in case you have a bad trip.

"It’s all to do with the chemical state of the body and your frame of mind. Later, there was lots of bad acid spiked up with rat poison and speed, but in the early days, when it was very pure, it was okay.”

LSD was certainly in the mix when Hawkwind recorded their debut, self-titled album at Trident studios in spring 1970. Produced by The Pretty Things’ guitarist Dick Taylor it was, says Huw, “a happening”.

He adds: “One day we took a hallucinogenic substance, and we couldn’t play a particular number because we couldn’t stop laughing about something – I don’t know what it was. The engineer was a very straight, be-suited, bespectacled guy, and he thought it would be a great idea to record us having a cackle and do something with it on the album, but as soon as he got the mics out, the laughter just stopped. He ended up doing cartwheels and all sorts of stuff to try o get everybody to laugh again. The poor bloke was so frustrated.”

The album consists of material that Hawkwind had been playing for months. Recorded live with just a few finishing touches added later, it captures exactly how the band sounded in 1970, focusing on long, experimental, blues-based work-outs delivered with a riot of mad electronic effects and spontaneous, honking sax.

“It definitely painted a picture of that Notting Hill hippie circumstance better than anything the old Pink Floyd had done,” asserts Huw. “I don’t care what anybody says.” Brock agrees: “I would call that a psychedelic album all right.”

But by now, things were becoming difficult for John Harrison, who much preferred a quiet round of golf to an acid-fuelled rave. And his problems really came to a head in the summer when Hawkwind retreated to a Cornish cottage for rehearsals. “I really liked John,” begins Dave. “He was the anchor man, a really good bass player.”

But… “He wasn’t into taking as many drugs as us. We were all a bit over the top in our drug-taking – LSD, organic mescaline, and we certainly used to smoke our marijuana. We did actually spike people up, but we stopped doing that after a while. Engineers wouldn’t drink anything because they were as paranoid as can be that we’d spike them up.”

Harrison was wise to his bandmates’ tricks in Cornwall: “No, no, I don’t want any drugs. No, I don’t want a cup of tea.” But eventually someone managed to slip some mescaline into Harrison’s glass of milk.

“We could see him playing golf on the moors, whacking the balls and running after them,” says Brock. “He really had a wonderful time.”

Not wonderful enough, though. And he refused to change his mind about his dislike for hallucinogenics.

“I think he got a bit fed up with our over-the-top behaviour and left,” continues Dave. “Also, he used to get pissed off when things would just dissolve into a state of anarchy on stage. Where numbers would go on forever, with Dik Mik making noises. John just vanished, really.”

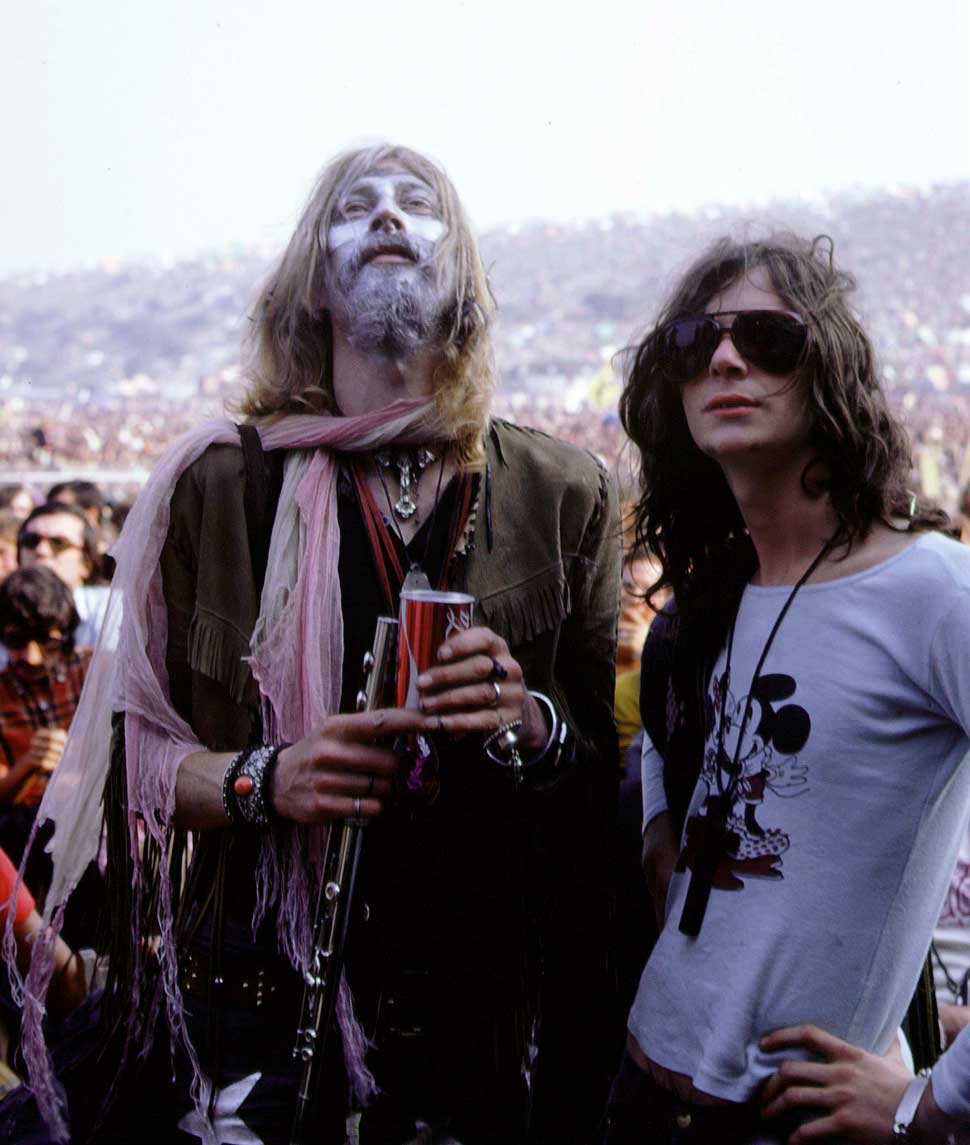

His replacement was Thomas Crimble, a bassist from the Notting Hill community, who took over in time for Hawkwind’s residency at the legendary five-day Isle Of Wight Festival. But the event quickly became a calamitous mess when almost half a million people turned up without tickets and demanded to be let in for free.

Hawkwind were not on the official festival bill, but they turned up to play a series of free gigs outside the perimeter, most of them in an inflatable dome called Canvas City. It was just before one of these gigs that Huw Lloyd-Langton took a huge swig of apple juice, only discovering afterwards that it had been heavily dosed with LSD.

He recalls: “I’d taken a tab of acid some months before, and I ‘died’ on that trip and went to not a very nice place. As a result, I’d decided not to touch the substance again.”

Initially he tried to soldier on with the gig. “I don’t know how many trips were in this apple juice. I didn’t want to ‘die’ again. Dik Mik, our dear old knob-twiddler, said: ‘If you fight it, everything turns negative. Just go with it. Let it flow.’ The guitar was stuck in my hand and I was told I had to do a gig. I started hallucinating at that point.

“I was led to the stage. It was absolute psychedelia, lots of gory flashing lights and people freak-dancing. As far as I was concerned, I’d just descended into hell. I was standing on a sort of padded mattress that was there to stop the dew getting into the electricity. Unfortunately for everybody, it was me that tuned the band up.

"I had my tuning fork and I got the note, but the note did what the mattress under my feet was doing, going up and down. So there was no way on earth I could tune my own guitar up, never mind tune everybody else up, and also, meanwhile, I was in hell, damned to be playing there for eternity.

“Eventually I just whacked a chord out and this cacophony started up. It must’ve been atrocious. About halfway through the gig, I actually got down on my knees and prayed that God would forgive me and release me from this situation. Finally we got out of the blooming place and I walked down to the sea and I baptised myself.

“Later Nik said: ‘You know on the stage when you got on your knees and prayed? That looked really good. Keep it in the set.’ What he didn’t realise was that I meant it. Only myself and God know what I was going through.

“I was still recovering from the trip the next night when I did a gig in this tent with Thomas Crimble. We played right through the night, from dusk till dawn. Afterwards, I felt vaguely cleansed. I don’t remember ever getting a better guitar sound; it was marvellous. This bunch of Brazilian percussionists were there, and they clicked in. Two or three people suggested that Hendrix came into the tent and sat there, and I was up there playing the shit out of my brain. One person said he suggested to Hendrix that he got up and played, and he apparently said, ‘No, I’d ruin it.’”

Hendrix also noticed an extravagantly made-up Nik Turner at the festival, dedicating a song to “the guy with the silver face”. Photographs of Turner later appeared in several national and international magazines, giving Hawkwind their first mainstream press coverage. As an additional benefit, they gained great kudos for taking a stand for free festival music, a policy they would champion for years to come. Their bookings – and their following – expanded accordingly, and they appeared in concert with all the major psychedelic bands of the era.

The hippie dream was dying in America, following Altamont and the Manson murders, but in England in 1970, the freak scene was alive and well and as idealistic as ever. However, Hawkwind were moving into their exciting future without Lloyd-Langton, who handed in his notice, still reeling from the aftershocks of the acid experience. In fact, he was heading for a breakdown, which started suddenly one night in front of the TV.

“Frankie Howerd was on,” he remembers. “I had a couple of puffs of this very strong dope and my eyes started flicking between the crap I was watching and this perfect, pure white flower that was on top of the telly – the good and the evil. The only way I can possibly describe it was that I felt my soul dying. I was frightened out of my flipping circumstance. I put that joint down and I didn’t touch any substance again for at least 10 years. Even now, I’ll only have a puff very occasionally, just to be sociable.”

Huw was out of action for quite a while as he wrestled with his sanity. He would return to Hawkwind nine years later after stints with popular touring acts including Widowmaker and Leo Sayer. For now, though, Dave Brock took care of all the guitar playing.

There were several other comings and goings in the Hawkwind ranks over the next number of months. After Christmas that year, Thomas Crimble left for what would be a 30-year career with Michael Eavis at the Glastonbury Festival organisation, making way for the next bassist, Dave Anderson – an English player formerly belonging to Amon Düül II.

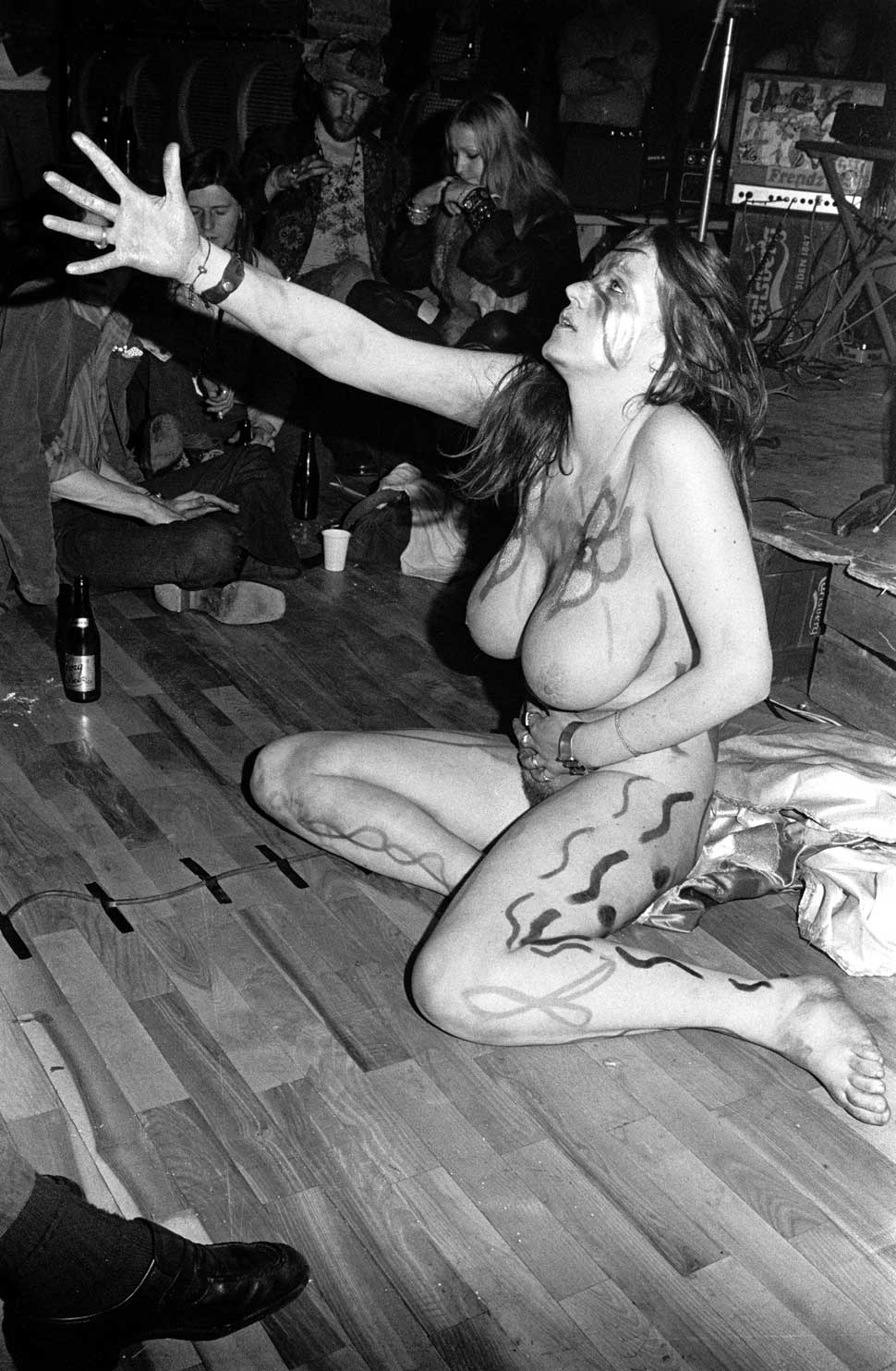

Hawkwind also acquired a huge new attraction – the enormous breasts of Amazonian dancer Stacia, who regularly stripped on stage to reveal a completely naked body painted with flowers and other colourful illustrations. Having first met Nik Turner at the Isle Of Wight Festival, Stacia turned up to see the band at Redruth, Cornwall, in April 1971, asked to dance with them, did, and was immediately invited to join the line-up.

“Free expression was the object,” says Dave Brock, explaining Stacia’s eagerness to disrobe. “People used to say: ‘I want to take all my clothes off and be free and jump around.’ That’s what she did. That was the whole thing with LSD – art, music and people taking their clothes off. Terry Ollis used to do the same thing because he used to sweat a lot behind the drumkit, so he took off all his clothes. It was that freedom.”

Del Dettmar, recruited at around the same time, was nevertheless committed to keeping his clothes on. Dettmar, Hawkwind’s gnome-like road manager, was promoted into the band for his synth and keyboards wizardry, and the formidable electronic partnership he forged with Dik Mik became a staple of the band’s sound – and also influenced later generations of dance musicians.

At the same time, Hawkwind were gathering a crack team of collaborators from among their creative cronies in Notting Hill: poet Robert Calvert (an old friend of Nik Turner’s); Michael Moorcock, the prolific science-fantasy writer; Barney Bubbles, the gifted designer; photographer Phil Franks; onstage DJ Andy Dunkley; and lighting designer Jon Smeeton, aka Liquid Len, who masterminded sensational light shows, helping Hawkwind progress from one big strobe to layers of spinning screen projections.

With the assistance of this amazing team, Hawkwind were moving towards the all-encompassing musical and visual identity they’d always dreamed of. But there was a shift in emphasis. Nik Turner once put it like this: “Originally, the thing was very much more inner space, not outer space. It was mind-expanding.”

With their next album, In Search Of Space, a Top 20 hit, Hawkwind would become pioneers and lifelong explorers of space rock.

And Lemmy wasn’t so much as a twinkle in anybody’s eye. Yet.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock Presents: The Doors & The Psychedelic Revolution (August 2008). The deluxe version of Hawkwind's In Search Of Space is out now.