At the end of the day, it’s not the how or the why that made Back In Black such a monumental release, but the what. Or in this case, the ‘what the fuck’? That’s to say, it’s not the tortuous story behind its making, but the sound of it, the sheer scale of it, that makes Black In Black what it is.

From the moment that tolling bell that opens side one begins to chime ominously, followed, on the fifth chime, by that body-being-dragged-from-the-river guitar, all the way across dark thunderclouds to the very end of the album, when Brian Johnson announces that rock’n’roll is ‘just rock’n’roll’ and the guitars and drums stub themselves out like a chewed-up cigarette. That feeling, that fuck-you blam-blam-blam.

Most of it is down to the production by Mutt Lange. Having already taken AC/DC’s bruised blues-and-rock street vibe and sculpted it into the arena-filling, radio-friendly Highway To Hell, Mutt went one notch higher – not to 11, but to infinity.

As Mutt’s fellow South African Kevin Shirley –who, as producer for such mega-acts as Zeppelin, Maiden and Aerosmith, would know – says of Back In Black: “It’s my all-time favourite album, next to Miles Davis and maybe a Beethoven violin concerto. It’s certainly the best rock record that’s ever been made. There’s just an incredible architecture to it. It’s the benchmark record for sound. The production on that record is so melodic, it just sounds so good. And it’s so well structured that it crosses the genres.”

With its cathedral-like production, its high-quality songs that still contained enough of Bon Scott’s DNA to afford them true greatness, and, most reassuring of all, with a new singer who had clearly taken to his task with the kind of relish Bon would surely have applauded, Back In Black was a better album than even the impossible-to-please Young brothers could have imagined. So resoundingly defiant of the bleak circumstances of its bloodied origins, it soon took on a life of its own, beyond the hopes and aspirations of the band or even their fans, and out there in the stratosphere where only the truly great rock giants lived.

Like all the best AC/DC moments, the key to their success is all in the grooves. So that even ostensibly bleak tracks like Hells Bells sound like a party you don’t want to leave. “It’s a lesson we learned in Def Leppard when we worked with Mutt,” says Joe Elliott. “A track doesn’t have to be fast to feel like it’s really rocking. AC/DC were masters of that on Back In Black.”

Same thing with the title track, which slithers like a snake yet hits like a speeding train; a sonic serpentine made even harder to resist because of the lyrics. Written, as was Hell’s Bells, with Bon in mind, Jonno, as he became known, would never sound so serious, so heartfelt or inspired, again.

Elsewhere, on other cornerstone moments like Given The Dog A Bone and Let Me Put My Love Into You, he showed he also had a penchant for double-entendre lyrics that almost matched Bon’s.

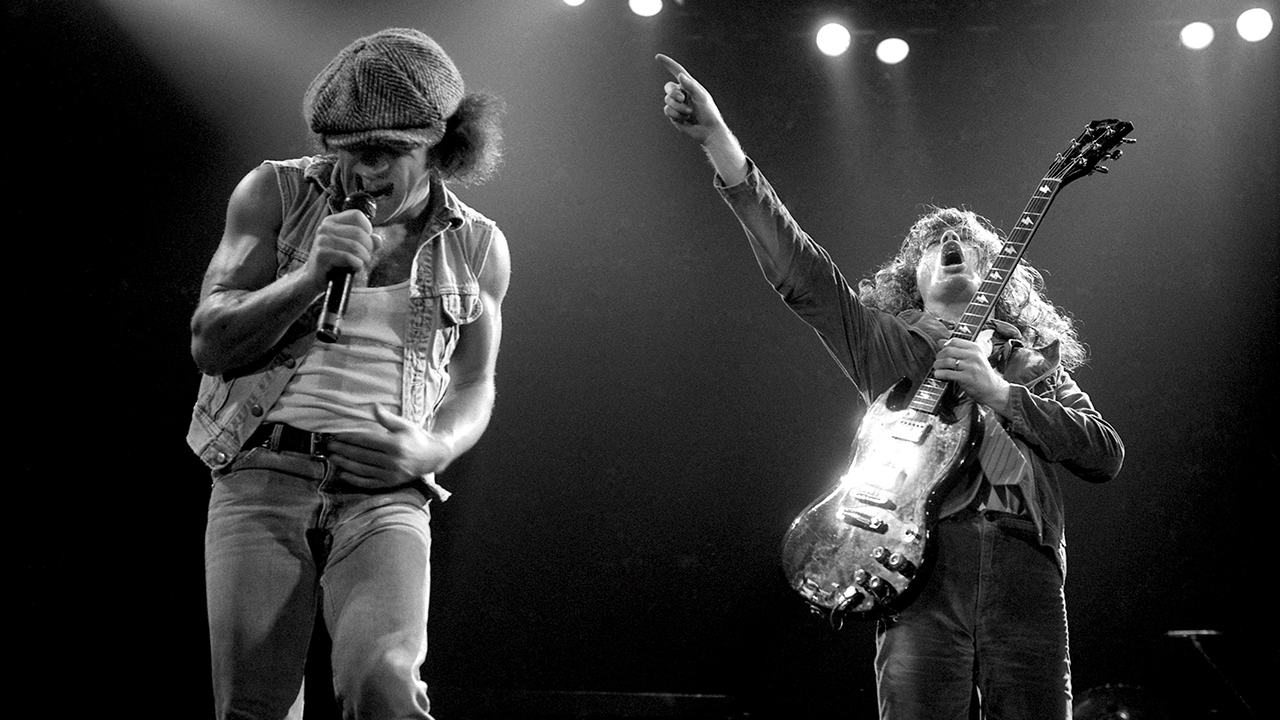

And then there was the voice. While there is little that is new about the music on BIB, save its next-level refinement, Jonno’s voice was a revelation. He may have looked like a cross between Albert Steptoe and Andy Capp, with his gamekeeper tweed cap and endless smoky tabs, but he had a voice like the sound of a giant who was gargling with nails, and a presence as warm and inviting as a pub fire.

According to the singer, however, there was a further presence involved in the music. Recalling how he wrote the lyrics to You Shook Me All Night Long, he said: “Something washed through me – this kind of calm. I’d like to think it was Bon, but I can’t because I’m too cynical and I don’t want people getting carried away. But something happened and I just started writing the song.”

Mutt’s engineer, Tony Platt, recalls the whole band coming up with lyric ideas too. “I can distinctly remember on You Shook Me everybody sitting down just throwing ideas forward. ‘Double time on the seduction line’ was one of mine. I’ll always lay claim to that one.” Some of the suggestions by the band were “too lewd and over the top”, others were “just too stupid”. What Do You Do For The Money Honey dated back, Malcolm said, to the original Powerage sessions three years before. George Young had come up with the title, and “we all chipped in” on the lyrics.

Later, the rumour spread that Bon had been the author of many of the lyrics. But while the band’s tour manager at the time, Ian Jeffery, recalls that “some scraps of paper with maybe a few words on them” had been recovered from the singer’s flat after his death, contrary to the conspiracy theorists’ claims there were no song titles, no completed verses, very little to go on, just his spirit.

Indeed, some of the tracks just seemed to appear out of thin air. Tony Platt says one of the easiest tracks to record was the straight-ahead rocker Shoot To Thrill. Almost one take. For Jonno it was the monolithic closer, Rock And Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution. “I didn’t know what to do at the start so you can hear me there having a fag. Mal just said to go with it, so I put my headphones on, put a tab in my mouth and just took a breath: ‘All you middlemen throw away your fancy cars…’ For some reason middlemen were in the news at the time. The top guys weren’t getting the blame and the work force weren’t getting it either, it was the middlemen who were this grey area. I must have picked up on it and it just went from there.”

Recorded in the Bahamas and completed in just six weeks, Back In Black, released just months after Bon’s death, would become what many still consider to be the greatest AC/DC album of all. It was certainly their biggest hit, with more than 40 million sales worldwide making it the biggest-selling rock album of all time.

The question now was: how do you follow that?

The answer was not one they would find easy to come by. In fact they didn’t even come close with the follow-up, For Those About To Rock… We Salute You, recorded at different studios in Paris, in the summer of 1981, again with Lange at the controls. While AC/DC arguably owed everything to Lange’s meticulous, almost OCD approach to record production, there was no denying the tensions his unusual methods were creating within the band.

As Mutt would later concede: “Some of them believe I was a merciless tyrant in the studio and obsessed with absolute perfection with each song.” Asked to describe a typical day in the studio in Paris, Johnson chuckled ruefully: “Angus, Malcolm and myself on a big sofa – waiting!” Or as Angus put it: “Just some guys that were bored shitless.”

It was that boredom that eventually translated onto the grooves of FTATR. Tension reigned throughout the recording. So while the brilliantly apocalyptic title song would become one of their greatest anthems, most of the rest of the songs most decidedly would not.

Starting as usual with a chorus and riff concocted by Malcolm and Angus, Johnson’s lyrical theme for the title track was supplied by a book Angus had come across about Roman gladiators titled For Those About To Die We Salute You, taken from the oath each gladiator would address the emperor with as they went into battle: ‘Ave Caesar morituri te salutant’ (‘Hail Caesar, we who are about to die salute you.’) “We thought: ‘For those about to rock’… I mean, it sounds a bit better than ‘for those about to die’,” Angus said:

A ‘journey’ song, in that it starts relatively slow before moving through the gears towards a tremendous all-guitars-and-drums-blazing finale, its other signature motif was the sound effect of cannons blasting off as a prelude to its scorching climax – inspired by the cannons fired at the wedding that summer of Lady Diana Spencer and Prince Charles. The band had been rehearsing the song when Angus noticed “the royal wedding thing” on the TV. At which point a lightbulb went on in his head. “I just wanted something strong,” he recalled. “Something masculine, and rock’n’roll. And what’s more masculine than a cannon, you know? I mean, it gets loaded, it fires, and it destroys.”

Unlike on BIB, almost all of the material had been written in advance. It should have been a case of simply going into the studio and bashing the songs out. But that wasn’t how Mutt worked. The results fell between two stools. On tracks like I Put The Finger On You, Let’s Get It Up and Snowballed, the lyrics had descended from double- to single-entendre, and the riffs were now being scooped from the bottom of the barrel – something that could never have been said of even their most mediocre Bon-era tracks.

With a band this all-conquering and a producer this brilliant, the overall effect could be powerfully felt when played at top volume. But there was little to keep bringing you back. Tracks like Inject The Venom and Night Of The Long Knives were parodic. The single-line choruses and pedestrian riffs were becoming – yawn – predictable.

There were better tracks – the groovacious Evil Walks, the swaggering C.O.D. – but these were exceptions. Some, like Breaking The Rules, started out sounding momentous then descended from their tremble-tremble intros into half-arsed rock-by-numbers affairs. Even the final track, the self-consciously climactic Spellbound, failed to live up to its billing. The production, once so awe-inspiring, sounded cumbersome, a whole lotta love wasted on thin material unworthy of the producer’s ardour.

“By the time we’d completed the album,” Malcolm Young later reflected, “I don’t think anyone, neither the band nor the producer, could tell whether it sounded right or wrong. Everyone was fed up with the whole album.”

With the recording finally wrapped at the end of September, Atlantic hurried to get the album out in time for Christmas. Released in the UK on November 23, 1981, For Those About To Rock was largely greeted with joy by fans and critics still basking in the heat of its mega-hit predecessor. It did not, however, follow Back in Black to No.1; it peaked at No.3 behind the Human League’s Dare and Queen’s first Greatest Hits. And while it provided the band with their first US No.1 album, sales were a fraction of what they had been for Back In Black.