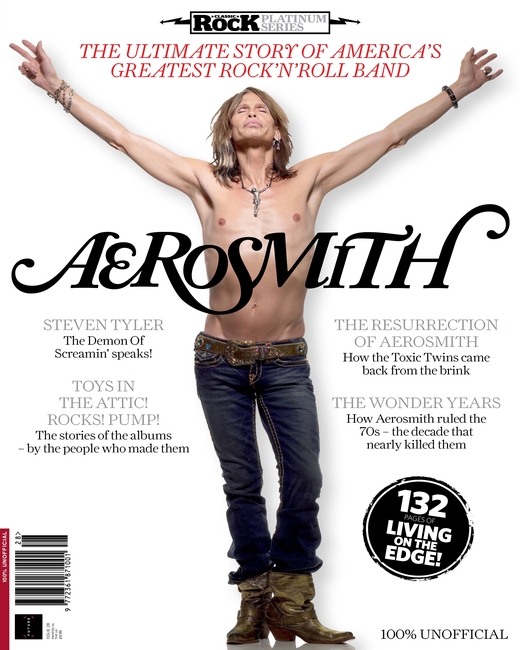

It’s January 1980 and Aerosmith are playing Reefer Head Woman from their new Night In The Ruts album at the Civic Centre in Maine. It’s a sold-out show, but singer Steven Tyler doesn’t care.

Frustrated at having no cocaine to counteract the intoxicating effects of all the booze he’s swallowed since waking – rounded off by two double martinis gulped minutes before taking the stage – he gives up and pretends to pass out. Throwing himself to the stage he fakes a seizure, twitching his leg to make it look authentic.

Such is his level of chemical dependency and alcoholic intoxication, this is the best idea he can come up with to avoid the indignity of playing a gig just plain old-fashioned drunk.

To this point in the tour Aerosmith have just about been getting away with it. Though with guitarist Joe Perry no longer in the band – replaced by JP-lookalike Jimmy Crespo – they are a shadow of their former selves. They’ve played shows where the singer has frequently forgotten his lines, and, when not at the mic has just sat on the drum riser, too unsteady to stand, much less move about.

Tonight it’s worse. The band stop playing, and Tyler is carried from the stage, a faker and a fuck-up.

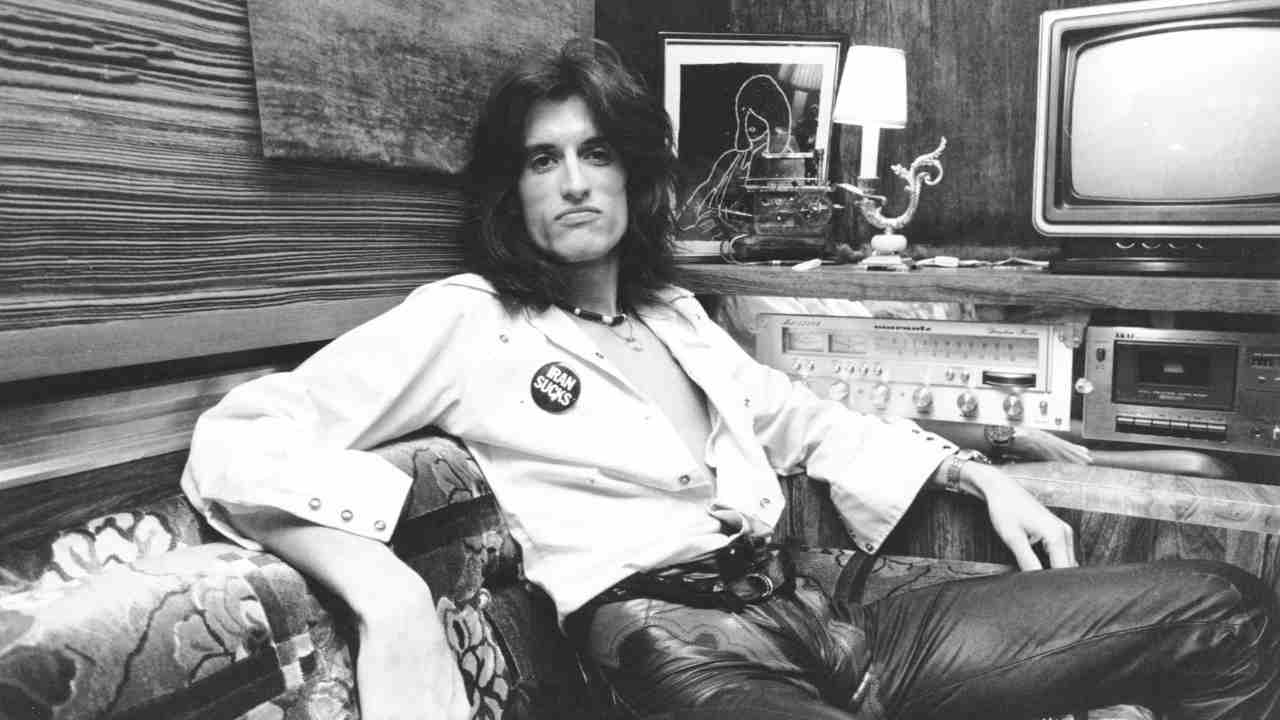

Elsewhere in early 1980, Perry is touring with his original Joe Perry Project. He feels liberated from the “dysfunctional depression” that was crippling Aerosmith and had forced him out of his own band – but now his new outfit faces ruin because singer Ralph Morman has turned into an out-of-control drunk.

“One night he showed up in a wild state of inebriation,” Perry recalls in his autobiography Rocks. “I hauled off and decked him.”

These days Perry acknowledges the irony. As the book candidly admits, he was not in good shape himself: a barely functioning drunk addicted to snorting heroin. Career-wise, The Joe Perry Project’s Let The Music Do The Talking album had been well reviewed, but was poorly promoted by Columbia and wasn’t troubling the charts. The gigs, though good, were small-scale. This was a problem – because Aerosmith’s co-manager David Krebs had not long since told Joe he personally owed $180,000 in room service charges and helpfully suggested that a solo album might be a good way to pay the bill.

For Aerosmith and for Joe Perry, however, things are going to get worse before they get any better.

The 1980s began less than four years after Aerosmith’s fourth album Rocks had shipped platinum upon release, rising to No.3 on the Billboard Hot 100. Hindsight suggests that Rocks, the multi-platinum follow-up to the multi-platinum Toys In The Attic, was where the ‘first career’ of Aerosmith peaked. Afterwards, their decline and fall would be as marked and meteoric as their rise had been.

After Tyler’s fake seizure, Aerosmith cancelled a week’s worth of dates – thereby falling a little further – then resumed and limped on to the end of the tour, and more drink- and drug-induced lethargy. When they reconvened, work on a proposed next album was painfully slow. Then that faltering progress all but ground to a halt after Tyler badly injured himself in a motorcycle crash. Silently but inevitably, poverty crept up and was soon crippling them all.

Bassist Tom Hamilton: “For two years, the album we were working on – Rock In A Hard Pace – was always two months away. It was hard times, we [Tom and his wife Terri] sold our house and moved into a condo…”

Drummer Joey Kramer: “It was rough. There was no money. I was on the balls of my ass. I spent everything I had… until, finally, nothing.”

Guitarist Brad Whitford: “No money, no income, all my savings going to alimony and mortgages. Sold my guitars… sold my house…”

Eventually Whitford could stand it no more, and quit. Aerosmith were down to just three original members, Tyler plus the rhythm section of Hamilton and Kramer.

As Perry’s marriage to fellow drug addict Elyssa continued to falter and debts mounted, he released the second Project album, I’ve Got The Rock’N’Rolls Again (featuring new vocalist Charlie Farren) in 1981. Whitford, meanwhile, hooked up with Ted Nugent’s singer Derek St Holmes to release the eponymous Whitford-St Holmes the same year. They toured briefly, but their record didn’t sell well.

On the recommendation of producer Jack Douglas, Aerosmith recruited Rick Dufay to play on Whitford’s side of the stage. It seemed like a good idea at the time, even though Dufay boasted to the singer that he had escaped from a “loony bin” having jumped out of a window and broken his legs…

The older, wiser and sober Tyler now reckons Dufay was “out of his mind”. Back then, though, the singer barely cared.

When the tour ended he “got deeper and deeper into drugs”, hanging out with and scoring heroin off his friend Richie Supa (with whom he’d co-written live favourite Chip Away The Stone). Somehow, stoned and hallucinating, he eventually managed to write enough lyrics to finish Rock In A Hard Place in time for release in August 1982. Good in parts, but a long way from former glories, it wasn’t a record that suggested the epic amount of time spent on it had been a wise investment. A Gold sales award – ending a string of Platinum hits for Aerosmith – and a Billboard chart peak of No.32 confirmed this.

Eventually, Tyler admitted to himself he needed help. He first tried detoxing at the Good Samaritan Hospital in New York in 1983 but, as he admitted in his 2011 biography Does The Noise In My Head Bother You?: “One of the reasons I wanted to go to Good Samaritan was that I heard they did tests on heroin… I thought: ‘Can I be one of the guinea pigs?’”

By then, Aerosmith’s Krebs was hiring psychiatrists to meet Tyler and report back with their thoughts. Domestically, Tyler’s fights with his wife of 12 years, Cyrinda, had turned physical and violent. Once, as she prepared to drive off, he jumped on her car and smashed the windscreen.

Tyler: “Cocaine insanity! She got out of the car and a violent, uncontrollable fight erupted. We were punching and scratching, and we fell over and rolled on the ground…”

For Perry, domestic life was no sweeter. Elyssa continued to spend money extravagantly, as if he were still a member of the 70s Aerosmith.

He recalled: “I was on the verge of losing my house. I was fucked up from drinking. I thought I was at the bottom, but every day that bottom kept getting deeper and darker.”

Sometimes, though, as the unexpectedly sage-like JK Rowling has observed, rock bottom can become a solid foundation on which to build a new life.

That new life – or “second career” as the five original, once-again-Platinum-selling members of Aerosmith are wont to describe it – was still a way up the road.

Perry was taking any gigs he could to earn cash – sometimes supporting the likes of Heart and the J Geils Band, always travelling in a van and staying in cheap hotels to keep costs low. Back home, he took the life-changing decision to walk out on Elyssa, after six-and-a-half years together – but paid a heavy price in the battle for access to their infant son Adrian.

He was happy to play with the Project, but the debts he faced weren’t going away. One good thing was happening in the guitarist’s life, though. He had hooked up with a new manager, Tim Collins, who became “the only steady force in my life”. The deal was sealed after Perry tested Collins’ commitment by emptying a drawer in which he kept his unopened mail: mostly bills, IRS claims and foreclosure notices threatening repossession of his home, but also some unsigned death threats (presumably from drug dealers he owed money) and royalty cheques worth thousands of dollars. Collins took them away in a grocery bag and came back a week later offering to pay off “a big portion” of the guitarist’s debts, no strings attached.

Asked why, Collins simply reasoned: “I figure I need to do this to win your trust. I believe in your talent. I believe your best years are ahead of you. I want to manage you.”

One of his first moves was to negotiate Perry out of his deal with Columbia and get him a new one with MCA. Perry disbanded the old Project and hired a new one (fronted by singer Cowboy Mach Bell) on smaller salaries to record their third album, Once A Rocker, Always A Rocker, in 1983. It wasn’t as good as the first two, but the band got to open for ZZ Top on some of their US Eliminator tour. The headline gigs they were playing, though, Perry says, “were getting smaller and smaller”.

He did persuade Whitford to join the line-up, however, and the rhythm guitarist stayed for a month. Kramer later played drums at a few dates, too. Much more significantly, though, Perry was about to meet his soulmate, who was discovered when the Project were about to make a video for their last chance at a hit, a song called Black Velvet Pants.

Perry: “Tim Collins had a bunch of books sent over by talent agencies, I thumbed through half-heartedly until I came to a picture that stopped me in my tracks – a headshot of a beautiful blonde called Billie Montgomery. There was a look in her eyes that got to me, heart and soul. I had to meet her.”

When he did meet her, it was love at first sight. And their relationship would endure long after the video shoot had wrapped, to this day.

Aerosmith, meanwhile, were in trouble. They were playing bigger venues than the Project but, as Tyler has admitted, the tour for Rock In A Hard Place was “a disaster”.

Tyler: “By 1983 I had no money and no future except getting further into the pit. Back in 1976, when I read stories about guys who lost everything and blew a million bucks snorting all they had, I used to say: ‘That’ll never happen to me.’ But in the end, I blew $20 million.”

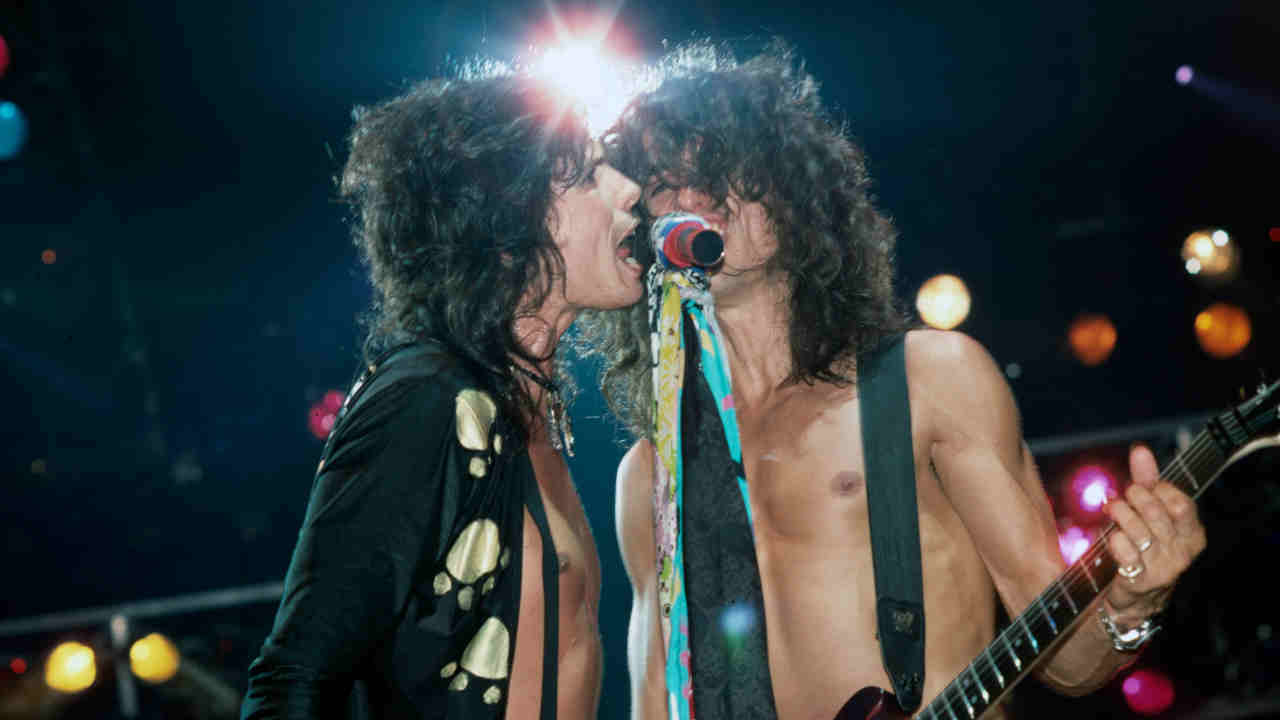

In addition, he came to admit that he was missing his buddy: “During the years that Joe and I were broken up I realised I wasn’t half the musician I thought I was without him.”

The two had kept in touch, though.

Perry: “I’d occasionally call Steven, or he’d call me… ‘How’re things going?’ Great, I’d lie. How about you? ‘Great!’ he’d lie… The bullshit flew thick and fast.”

Tyler: “I went to see the Joe Perry Project perform at the Bottom Line, then Joe came to the Worcester Centrum in the spring of 1983 to see an Aerosmith concert. We did a few lines of heroin in the dressing room – just for old times’ sake…”

The heroin took its toll on Tyler, who collapsed on stage in front of 14,000 people… and although it had been Tyler’s wife Cyrinda who supplied the drug, Perry took the blame, with Tom Hamilton lambasting him: “It’s just like the old days, Joe. You’re no good for this band. Look what you did! Why don’t you just stay the fuck away from us?”

Yet the idea of a reunion persisted.

In early 1984, Tyler and Perry met with Tim Collins and, despite some initial friction, Tyler – by then living in a hotel on $20 a day – agreed the original line-up should get together for a meeting at the only place available: Tom Hamilton’s house.

Perry: “If you want to put it on the IQ meter, Tom is a really smart guy, but I think he had just been more conservative with his money and watched what was going on. Also, he didn’t have to go through a divorce. He’s the one who’s been married the longest among us.

“Any professional who has to go through a divorce, the finances are going to take a real hit. It’s one of those things in life, it isn’t peculiar to rock’n’roll. If you’re making a lot of money, they take a lot of money.”

Once it became apparent that Joe would only rejoin the band on the condition it cut all ties with Leber-Krebs Management and joined him with Tim Collins, they set about discussing a way forward and naming a scapegoat for all their problems. They settled on David Krebs.

Perry: “The main influence that the drugs will have had was that we were partying too much and didn’t notice the kind of money we were spending or take care of the decisions we were making – I don’t think we could have spent that much on drugs! And it’s not like we all had three houses and 16 Maseratis. We all had one house and a couple of nice cars, and that was it.

“I look back and just think we were taken advantage of, maybe in some quasi-illegal ways. You just have to do the numbers in your head: all those years we were selling out so many arenas, so many times. So to sit there and be told that the band’s kitty was empty, I mean – did they do something illegal? I don’t think so. We couldn’t prove anything. Was it immoral? Yeah!

“They weren’t taking care of us in terms of taxes and things like that. I should have been more on top of it but that was my own naïveté. There was a lot of money there, just lying on the table, and people took it because they could. That is the story. I can’t prove anything – but I was constantly asking for accountings and things like that, but it was kinda tough to get the rest of the band to lock up.”

While the reunion idea was left hanging, a third party was about to plant a crucial seed. Alice Cooper was looking for a new guitarist, and his manager Shep Gordon called Collins to sound out JP. Seeing no long-term future for the Project, Perry jumped at the chance and went to Gordon’s county pile to meet and jam with Alice. The next day, while Alice played golf, Perry called Tyler to gloat. At the time Tyler pretended not to care but deep down he was incensed. His book suggests he remembers the incident differently to Perry, but says that he later called him back:

“Are you seriously going to be his guitar player? What the fuck? That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard! Just stop. The shit’s over. Why don’t you just come back with Aerosmith?”

Well, since Tyler had asked so nicely, how could Joe refuse?

Initial rehearsals were fraught with tension, but gradually the band found something like their old groove, reworking old songs they remembered and discovering others they’d forgotten. Collins built a support network, hired a crew and so the band – crucially, still drug-dependent at this point – went out on what was dubbed the Back In The Saddle Tour. Some shows were good, some were horrible, but fans were stoked and tickets sold. The tour ran from late June to end of August then, after a break, from December into January 1985.

Meanwhile, Tim Collins set about courting record labels. One of the keenest was Geffen, as represented by weirdy-beardy teetotal A&R man John Kalodner.

At first the band were sceptical, viewing him as just another record company guy – albeit looking like a guru in his white suit and long hair. Financially burned and emotionally fragile, they didn’t trust outsiders. But Kalodner kept showing up, to see if these 70s legends might still be worth a deal in the 80s. In the end, at a show at LA’s Greek Theatre, a link was forged while Kalodner was talking with Brad’s wife, Karen. She showed him the gun she always carried and, in Crocodile Dundee style, he showed her his.

Kalodner recalled: “I pulled up the trouser leg of my white suit and showed her the .357 Magnum I was wearing in an ankle holster. ‘This is how I get around LA,’ I told her. I was showing off, but it worked. As soon as the band found out I was packing dynamite, they thought I was totally cool. It broke the ice with them because they loved guns.”

A deal with Geffen followed. Next they needed a producer. Tim Collins instructed Kalodner to get them Ted Templeman, who’d just hit platinum with Van Halen’s 1984 – though the band’s admiration for Templeman stemmed from his work on Montrose’s debut.

In a rehearsal space in Somerville, Massachusetts, the band knocked together “17 new songs in four weeks”. Judging by the eight that made what became the band’s eighth studio album Done With Mirrors (its title a reference both to magic and a cocaine user’s preference for snorting the drug from reflective surfaces), few were up to scratch. On day one, they ran through most of them and Tom Hamilton insists: “I think we wound up using most of the takes from that first day of just slapping them down on tape.”

Two weeks before the record was due to be mastered, Tyler was in his hotel room trying to write lyrics. It didn’t bode well.

Perry: “We were still doing everything like we had before. Everybody was still… dabbling. We thought we could continue the same way.”

Kramer: “Done With Mirrors sounds to me like an incomplete record, without the finishing touches, the nuances, the personalities.”

Kalodner was even more disappointed: “When I realised the only good song was Let The Music Do The Talking – an old Joe Perry song – I knew we were in trouble.”

He was right. Hardcore fans liked it but, outside the rock charts, there were no hits from Done With Mirrors. To get back in the charts, the band were offered a most unlikely route. A call to Collins from Rick Rubin of hip hop label Def Jam Recordings saw Perry recording guitar tracks and Tyler adding vocals to a new version of their 1975 hit Walk This Way, by New York rappers Run-DMC. The track was done in a day on March 9, 1986, and the famous “breaking down the walls” cross-culture/anti-racism video shot two weeks later.

Although plans to work further with Rubin faltered (yielding only their cover of Rockin’ Pneumonia And The Boogie Woogie Flu on the Less Than Zero soundtrack) the single became a crossover hit. It reached No.8 in the R&B/Hip-Hop singles chart and No.4 in Billboard’s Hot 100 after the video proved a huge hit on MTV. Although only two of the members had been involved, Aerosmith’s profile grew and the name reached a whole new generation, in the US and in Europe.

While their old management tried to sue the band, and their former label muddied the waters by releasing compilation albums (including Classics Live!, featuring the Crespo/Dufay line-up), the Done With Mirrors tour ran out of steam, the album having sunk without trace.

Tyler had tried rehab on three further occasions – encouraged by his band-mates who reasoned that as long as the singer was sober, they could continue getting high and function behind him. Predictably, Tyler didn’t agree and simply rebelled and lapsed.

The band and Collins persisted. Tyler and his new wife-to-be Teresa checked themselves into a methadone clinic and made progress. But this was not enough to satisfy everyone, and so in the autumn of 1986 Tim Collins hired a therapist to call an intervention on the singer. Once again, objecting to being singled out as what he called the “designated patient” while knowing full well that the band (and Collins) were as guilty as he, the intervention felt like an assault to Tyler. But the power of his peer group proved irresistible. Tyler entered rehab once more, this time emerging fiercely determined to make his band-mates and new manager do the same. This time: success.

One by one – starting with Joe Perry in October 1986, following the birth of his second son Anthony – the rest of Aerosmith went through rehab, too. For some, the respite lasted only two or three years – but they never fell so far from the wagon as they’d been before. For Tyler, it was good for 12 years – enough time to allow Aerosmith to soar to the end of the 1980s as successfully as they’d done in the previous decade. Except this time, they were healthy.

Perry: “We realised after Done With Mirrors that we had to be done with mirrors – we had to change the way we were doing things. One of those was getting fucked up and partying too much.

“So we cleaned up and finally that creativity could happen again. It was the final step. We proved we could sell tickets, going out without a record, touring just on the strength of our name and to show that the original line-up was back together. But we just needed to make that one final step.”

That step was 1987’s Permanent Vacation. Tyler described it as “the best album we’d made in 10 years – and the first one we ever did sober”. It was also, famously, the first album where they called on the services of writers from outside of the band.

That process was instigated by A&R man Kalodner, who insisted that, after the failure of Done With Mirrors, the band make their next record his way – by bringing in fresh blood to help them write. He persuaded Aerosmith they needed to score some hits, and that they could do so without selling out their hard-rocking roots. His first call had been to Jim Steinman but, because Steinman didn’t want to work away from his house, he didn’t get the gig. The plan to use Ted Templeman once again ended when the producer baulked at Kalodner’s insistence that, unlike on Done With Mirrors, the band’s A&R man be allowed in the studio to keep an eye on progress.

Kalodner’s golden ticket solution was for Aerosmith to go to Little Mountain Sound studios in Vancouver to record with producer Bruce Fairbairn – the man at the helm for Bon Jovi’s multi-platinum Slippery When Wet, recorded the year before. Fairbairn’s team included Jim Vallance, who had co-written every song on Bryan Adams’ 1983 album, Reckless.

Perry: “Bruce had a little clique of talented musicians, a real scene up there. Vancouver is a great place, I love that city, there’s a lot of creativity there. Jim Vallance was the nicest guy you’d every want to meet and hang around with. It was really fun working with him.

“Keyboards and guitar were his two main instruments, but I’m sure he could play drums, too. Being a songwriter, I think he could play anything, to some degree. But he was also getting into that whole computer thing. Jim was one of the first guys to use computers to write programs for different drum patterns. That was really where he and I locked up.

“For me the biggest inspiration comes from the drums. When I first played with Steven he jammed on drums. I’d see him play in bands when he was a singing drummer, and when I put this band together, that was what I envisioned. His singing was top-notch but when he drums he’s not just hitting them, he really thinks about the song. He has this way of turning the beat around and that’s inspiring to me.”

For Tyler, the most important part of Team Fairbairn was Desmond Child. Born in Cuba as John Charles Barrett, Child was 34, five years younger than Tyler when they met. Behind him was a short recording career alongside two girls in Desmond Child & Rouge, and a far more successful career writing songs for the likes of Kiss (including the disco hit I Was Made For Lovin’ You and Heaven’s On Fire), Cher, Bonnie Tyler and… Bon Jovi. He enjoyed a co-credit on Livin’ On A Prayer and You Give Love A Bad Name, songs that had yielded the band No.1 and No.7 placings, respectively, on the Billboard chart, as well as two Top 20 hits in the UK.

Tyler: “I’d written with the band and I’d written with Richie Supa, but Richie and I were best friends. Desmond Child was another matter all together.”

According to Tyler, Child walked in sporting a moustache and looking “dapper”. They hit it off instantly, although not necessarily in a good way.

“I loved writing with Desmond because we always got into arguments,” said the singer, without irony. “When Desmond started throwing things at me that I didn’t know how to use I should’ve said: ‘Nah! I can’t sing that.’ But it took me a couple of years before I could voice my objections that strongly.”

One of the first songs that they worked together on was Dude (Looks Like A Lady), which at that stage was a Tyler/Perry composition that the singer recalls had a largely finished lyric but, much to his frustration, lacked a first verse. Child gave it to him with the line ‘Pull into a bar by the shore’. Tyler loved it and flung ‘Her picture graced the grime on the door’ right back.

Two lines later, though, the fledgling partnership hit a bump in the road. After Tyler’s ‘She was a long-lost love at first bite’, Child proposed: ‘I threw my money down on the stage/And, well, I didn’t care.’

Tyler thought that “fey” but, in an uncharacteristically tactful reply, merely complained it didn’t rhyme, and then fixed it himself with ‘Baby maybe you’re wrong/ But you know it’s all right’. The rest is rock history.

Dude… was the first single released from Permanent Vacation, in October 1987 and took Aerosmith to No.14 in the Billboard chart. It later took on a life of its own thanks to the promo clip shot for MTV, its brilliant title (inspired by Mötley Crüe’s over-use of the word ‘dude’ during a New York bar-crawl on which Tyler was present), and its later use on the soundtrack to movies Mrs Doubtfire and Wayne’s World 2.

An even bigger hit, however, was power-ballad Angel – co-written by Tyler alone with Child.

These days Perry looks back on the song with mixed feelings, and describes its creation in his book as “a turning point”.

Perry: “I would say that was the start of a big change. Steven and I always had this ‘team’ thing – we would get together and write. Okay, over the years, obviously, he wrote some songs with Tom and with Brad too, but he and I had this thing that was tight, you know? We were friends. He was probably one of the guys I hung around with the most. We didn’t go out as a band together because we had other interests. That was how he and I, right from the start, hooked up.

“The band always felt like a democracy – all for one and one for all – but Steven and I had this thing that was one step further, like a lot of songwriting teams in rock’n’roll history, I guess. So it just surprised me that he would sit down overnight and do that.

“I literally lived five minutes away so it really shocked me that he didn’t phone up and say, ‘We’re working on something new, come over.’ When I found out he had it was like: Wait a minute, I thought we were friends. I thought we were songwriting partners. It just didn’t even cross his mind that it would be a blow to me.”

Perry, note, had no problem with the song itself... Indeed while some hardcore Aerosmith fans saw the song as overly commercial, the ballad style and format was part of the band’s DNA. Their first album contained Dream On, the second Seasons Of Wither, while Toys In The Attic and Rocks closed with You See Me Crying and Home Tonight, respectively. And although that softer side was mainly down to Tyler, Perry himself did it with Play The Game off the third Joe Perry Project album, I’ve Got The Rock’N’Rolls Again. As much as they were known for hard rock, part of Aerosmith had always been an AOR band.

Permanent Vacation was released at the end of August 1987. In October, amid a flurry of interviews revealing how they’d kicked the habits that had been killing them, the reborn Aerosmith took to the road in America. The tour would run until September 1988 and take them back to the level of their mid-70s heydays. Before the tour’s close, the album would be certified double platinum in the US, with Angel reaching No.3 to become their biggest hit to date, surpassing even Dream On when it was re-released in 1976, off the back of Toys In The Attic’s success.

In February 1989, after a four-month break, Aerosmith took that success and euphoria back into Little Mountain to hook up with Bruce Fairbairn and co once more, to make Pump. Released three months before the end of the decade in which they’d reached rock bottom, Pump took them to their greatest heights yet.

“Pump really felt like that band had back in the 70s,” says Perry. “I sometimes get confused talking about Pump and Rocks. . . Those are two hot points in our two careers.”

Pump yielded six singles to Permanent Vacation’s four, reached No.5 in the Billboard chart and No.3 in the UK. The success fuelled a 12-month tour that began in Europe in October – a territory they’d avoided since a few tentative dates in the late 70s – and continued around the world, ending in Australia. Aerosmith were, finally, a global act.

Tyler: “The best tours are the ones that are propelled by hit singles. The tour’s the surfboard, the wave is your popularity. It’s a wave 20 feet tall, and you’re riding that fucker as long as you can.”

Aerosmith were back, and as big as they ever were. Impossible as it seemed.

Perry: “The odds of one person staying sober were small. But five guys? Unheard of. In this business no one gets a second chance. Yet we were more successful than ever.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Aerosmith