"If you were playing with two other rock bands, you wanted to be the band that people remembered when they walked out": How Aerosmith got their wings and flew

With their label ready to drop them after a so-so first album, Aerosmith clung on, dreamed on, and recorded a second that gave them lift-off: Get Your Wings

In June 1973, Aerosmith were a busted flush. Their first, self-titled album – released just six months before – had sold barely 30,000 copies, and Columbia Records president Clive Davis, who had signed the band less than a year earlier, informed them he would not be picking up the option for a second album. As guitarist Joe Perry says now: “We were out on our asses before we’d even got started.”

Talking to Classic Rock, Perry explains: “Your average person doesn’t realise how important being on a record label was [back then]. We had to audition three times to get the deal. They were like the bank, they fronted you.”

However, when Davis was fired that summer for alleged misuse of company money, the band’s management seized the opportunity to persuade the label to release Dream On, the standout ballad on the Aerosmith album, as a single. A multimillion-selling Top 10 hit when it was re-released three years later, first time around it reached only No.59 in the US, but the radio play it received helped it shift several thousand more.

There was also what singer Steven Tyler called “the cool quotient”. In September 1973, Dream On was added to the jukebox at Max’s Kansas City, New York’s hippest rock venue, conferring a degree of cool the Boston-based band otherwise lacked. With Dream On also voted single of the year on Boston’s influential radio station WBZ-FM, it bought Aerosmith enough goodwill for Columbia to offer them a ‘contract extension’, long enough to record a second album that would offer them one last shot at success.

Knowing it was make or break, for the next four months the band shared an apartment on Beacon Street in Boston. “We were getting a hundred bucks a week,” Perry recalls. Most of which, he later wrote, went on “Quaaludes and blue crystal meth we kept in the freezer”, along with “plenty of hash joints rolled like massive Jamaican spliffs”.

It was here where Perry came up with the swaggering riff and Steven Tyler wrote the lyrics to future Aerosmith classic Same Old Song And Dance, and frontman Tyler worked, with the aid of “a few Tuinals” and incense, on his epic ballad Seasons Of Wither. Perry, who detested the idea of rock bands doing ballads, later confessed: “Of all the ballads Aerosmith has done, Wither was the one I liked best.”

In October they hit the road opening for Mott The Hoople, whose 1972 US hit All The Young Dudes and new US Top 30 album Mott had made them a hot ticket. “All the English bands, with their accents and clothes, were the coolest,” says Perry. “But we learned a lot.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Aerosmith also played shows with the New York Dolls, who the hip music press fawned over, “but didn’t connect with the real rock fans, who were more into us”, offers Perry. “Our audience was basically kids the same age as us. They didn’t give a shit about fashion and neither did we. We just went out and kicked fucking ass.”

Between gigs, between being wasted, between “seeing more ass than a toilet seat”, as one former insider put it, the band continued to prep material for the album. The bones of both S.O.S (Too Bad) and Pandora’s Box were performed for the first time at these shows. S.O.S stood for Same Old Shit, and was Tyler’s dirty-dog pean to the ‘loose ladies’ of the road. Or as he sang it: ‘Stagecoach lady, hourglass body, making things glow in the night…’

Pandora’s Box, unsurprisingly, was not some spiritual rumination on the Greek myth, but about a girl named Pandora and the wonders of her, er, box. Written on a battered old acoustic guitar retrieved from a dumpster at the back of their apartment one night by drummer Joey Kramer – the same junk six-string Tyler wrote Seasons Of Wither on – it rewarded Kramer with his first co-writing credit for the funk boogie. It also allowed Tyler to further indulge his fondness for unfettered sexual innuendo: ‘Sweet Pandora, God-like aura, smell like a flora/ Open up your door-a for me…’

Another new number built on the road was Woman Of The World, a low-slung rocker co-written by Tyler with Don Solomon, the keyboard player from his earlier band Chain Reaction. The song had developed out of their freak-out jam version of Fleetwood Mac’s ode to masturbation Rattlesnake Shake, which the band had been playing for some time.

Another major highlight of the live set, and consequently of the new album, was their updated for the Quaalude-and-red wine generation version of Train Kept A Rollin’. Originally an old jump blues with ‘borrowed lyrics’, it was remodelled in 1955 as proto-rock’n’roll by Johnny Burnette, and reinvented a decade later by The Yardbirds as psychedelic blues, featuring Jeff Beck’s fuzz-toned guitar, then later ‘updated’ after Jimmy Page joined the group with ‘new’ lyrics as Stroll On, as seen in the 1966 movie Blow Up.

What Aerosmith did to Train… was add a ton of rhythmic weight and extended guitar soloing, stretching the three-minute Yardbirds version to almost twice that length. With its bulldozing staccato rhythm, Train became a show stopper that the band often ended their shows with.

As Get Your Wings producer Jack Douglas would recall: “When Aerosmith came back off the road, they not only were road warriors, they were killer musicians, they rocked so hard.”

Tyler, always so ‘on’ in public, had privately been glum at the band’s prospects. Now, with studio time at the Record Plant in New York booked for December, and Dream On still dangling from the charts, things were starting to vibe. Columbia had only one stipulation: that they hire Bob Ezrin to produce the record. Still only 24, Ezrin was on a winning streak. In 1973 he’d produced Alice Cooper’s biggest-selling album ever, Billion Dollar Babies, and Lou Reed’s controversial yet brilliant Berlin, a commercial disaster in the US but a Top 10 hit in the UK.

As Perry says: “Bob was hot as a pistol.” Unfortunately he just didn’t dig Aerosmith, seeing them as little more than a poor man’s Alice. “Over the years I’ve gotten to know Bob well. He’s a really great guy. But we got lucky with Jack.”

When Ezrin suggested his trusted engineer Jack Douglas should handle the ‘day-to-day’ in the studio, it sounded like a demotion. But Douglas turned out to be just what Aerosmith needed right then. Bronx-born, he was roughly the same age as Tyler and Perry, so they could relate. He had already gotten his wings, working on albums for Alice Cooper, The Who, John Lennon and the New York Dolls. This may have been his first rodeo as producer, but he’d been around the block, and knew exactly how to get the best out of this band of reprobates.

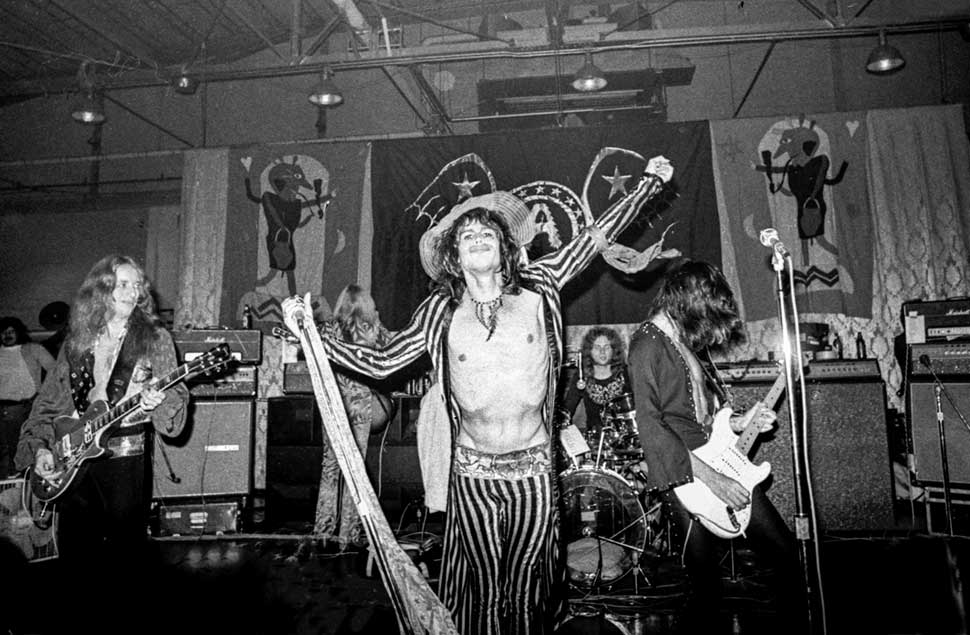

The first time he saw them play, he recalled: “The band came on in stage clothes – very glam but still very street. I’d seen Jimmy Page’s Yardbirds, and that night I thought I saw the American Yardbirds – not a copy, not an imitation, but the real thing, a hard-rocking blues, R&B rock group. I’m thinking to myself: ‘This is a great American rock band!’”

Having flown up to Boston to meet the band, Douglas found them “in the back of a restaurant that was like a mob hangout,” where they played him the songs they had so far. “My attitude was: ‘What can I do to make them sound like themselves?’”

Unfortunately, from Perry’s point of view, Douglas decided the best way to make Aerosmith ‘sound like themselves’ was to bring in session guitarists Dick Wagner and Steve Hunter.

Relocating in December to Studio C of the Record Plant in New York, Perry was affronted by the news. “We had a good batch of songs. Some we were already playing in our set, some original stuff, a couple of covers. Then they sat us down, me and Brad [Whitford, fellow guitarist] and said: ‘Listen, we want to bring in a couple of guitar players to play on a couple of the songs.”

Wagner and Hunter were Bob Ezrin’s go-to guitarists in the studio. Wagner had played lead on Alice Cooper’s Schools Out and Billion Dollar Babies albums, Hunter had also played lead on half a dozen of the BDB tracks. Both men had also appeared, at Ezrin’s request, on Reed’s Berlin. And as soon as they’d completed the Get Your Wings sessions they began rehearsing for the concert at Howard Stein’s Academy Of Music on December 21 that would become immortalised on Lou Reed’s classic live album Rock ’n’ Roll Animal.

“Well, that was Bob Ezrin’s MO,” Perry says wearily, still pissed off half a century later. “Like a lot of producers, they have their team. And they were great players, great studio guys. He said: ‘Listen, we want them to come in and sit in on a couple of tracks’.”

The tracks in question were Same Old Song And Dance, which Wagner played the blistering lead on, and S.O.S (Too Bad), which also benefited from his technical finesse. Both Wagner and Hunter handled all the soloing on Train Kept A Rollin’, Hunter the first half, Wagner the second. According to Brad Whitford, speaking earlier this year, “I don’t think I made it onto Lord Of The Thighs, either.”

Douglas later admitted that Perry and Whitford “wanted to kill me. ‘What! On our own record. Some of the most important leads on our own record?’ I said: ‘But no one will ever know. There would be no names on the record.’” He added: “Steven, by the way, was totally with me on this.”

“The thing is, we were playing those songs every night,” says Perry. “We were playing those songs the way that we wanted to play them. But we figured, listen, I’d never been to a recording studio until we did the first album. And the second album was the Record Plant as opposed to the small studio we’d used in Boston. We were in New York, we were starting to roll with the big dogs and it was a little daunting coming out from where we were. So we just bit the bullet, man.”

He goes on. “I mean, we didn’t like it, but we knew that in the bigger picture we wanted to get that second record out. We knew we had some great songs and that was the most important thing. So it just went down that way. Brad and I learned a lot about watching those guys do the few things that they did, and we picked up the ball and ran with it. You can tell by the next record how far ahead we got because of it. It sucked, but fuck, man, it was different back then. If you didn’t have a record company, you didn’t get your music pushed. And that was it. Out.”

Another Ezrin session team, the Brecker Brothers, were hired as part of a larger horn section providing saxophones, trumpets and trombones to Same Old Song And Dance and Pandora’s Box. Douglas also took the liberty of adding crowd noise at the end of Train…, which he’d lifted from a “wild track” from The Concert For Bangladesh, which he’d also engineered. “Most people were fooled,” he said.

Another Douglas-driven decision was that Tyler should use his real singing voice, as opposed to the somewhat contrived vocals on the Aerosmith album. “It was like a made-up voice that he thought sounded English or something. I said: ‘You gotta be kidding me. With the pipes that you have?’” Or as Tyler later put it: “On the second album, the songs found my voice. I realised that it’s not about having a beautiful voice and hitting all the notes, it’s about attitude.”

Once in the studio more material began to emerge, “with a lot of input from Jack”, according to Perry, such as Spaced, which was influenced by the emergence of ‘space rock’ bands like Hawkwind, who Aerosmith had opened for.

By the start of 1974 the album was almost finished. But they still needed one more song. Hunkered down at the Record Plant, they came up with Lord Of The Thighs, which Tyler had written, and which bassist Tom Hamilton described as “a portrait of the street life we used to encounter walking up Eighth Avenue [to our hotel] at dawn”. Like a scene from Taxi Driver, he said. “The girls in the satin hot pants, the pimps with the big velvet hats.”

Douglas recalled how Tyler would pick up “these amazing phrases” from the dawn chorus of hookers and drug dealers that would later appear in his lyrics. “Steven had an ear for that.”

The title was a pun on William Golding’s allegorical novel Lord Of The Flies, and the funky drum intro to the track would be repurposed a year later for Walk This Way, which would become their second Top 10 hit (but only, like Dream On, after it had been re-released as a single a year after that). The original working title for the album had been Night In The Ruts (resurrected in 1979 for the ill-fated album that saw Douglas being fired and Perry walking out halfway through), but it had been ‘announced’ by Tyler in a November 1973 press release as being Crystal, in clear reference to the blue stuff in the fridge on Beacon Street.

In the end it was Tyler who came up with the Get Your Wings sobriquet. As he explains in his autobiography, Does The Noise In My Head Bother You, the phrase ‘get your wings’ “is a Hells Angels thing. If you give a girl head when she has her period, you’ve got your wings.”

It all added up to a musical and attitudinal template that Aerosmith would build on and turn into one of the most successful careers of the 70s as platinum albums and sell-out US tours became the norm for the band.

Released in March 1974, Get Your Wings was a relatively modest chart hit at the time, sneaking just inside the US Top 100, but the singles from it – Same Old Song And Dance and Train Kept A Rollin’ – both received heavy airplay. Aerosmith were finally on their way.

The album even picked up good reviews, including a thumbs-up from Rolling Stone, who came up with the ultimate tag line: “They think 1966 and play 1974 – something which a lot of groups would like to boast.” Creem magazine went even further, describing the music as “primordial punk”’ and proclaiming Tyler “the new Lizard King”. But it was Joe Perry who best summed up Aerosmith’s new-found acclaim, when he quipped: “There’s no substitute for arrogance.”

Aerosmith certainly pulled no punches, staying out on the road for the rest of 1974, opening for Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, Blue Öyster Cult, Argent, Slade, Suzi Quatro, The Guess Who, Santana, Kiss, Hawkwind and more. They also headlined their first two sold-out shows at the Orpheum Theater in Boston, capacity 2,700.

When just two months later they returned to their home town to headline the 6,000-capacity Boston college, there was a riot. They were also starting to see some money for the first time. According to Tyler, they were getting $2,500-3,000 a show “where they knew us”, and $750 per show “where they didn’t”.

As Perry says: “You had to deliver. There was definitely competition. If you were playing with two other rock bands, you wanted to be the band that people remembered when they walked out. Still, there was also a lot of friendship and a lot of partying with the other guys, meeting everybody.”

He says now: “How we were all up fucked up and arguing” doesn’t reflect “the great time we had. We were all for one and one for all, all in it together.”

In August, Aerosmith received the ultimate stamp of grassroots rock approval when they were booked to appear on NBC’s Friday night rock TV show The Midnight Special, which actually aired at 1am straight after the final week’s episode of Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. The first chance America’s record-buying public had to witness Aerosmith outside of their live concerts, the band stormed the show, performing a killer Train Kept A Rollin’ followed by an equally steaming Dream On.

“We’d just come out of that era in America where Hullabaloo and Shindig were the big American shows.” Like Top Of The Pops in the UK, however, those were chart-oriented shows where the acts all mimed to their latest singles. “But Midnight Special was the one that you played live, and it was a big deal.”

It sure was. In fact you can now see for yourself how big a deal it was on YouTube. When I ask Perry if he’s seen the online clips of the show, he laughs and admits he hasn’t. “I should check it out,” he says. “Maybe I’ll get some ideas for clothes for the next tour.”

Talking of tours, until announcing their recent retirement Aerosmith travelled via private plane, but back in ’74 they were still travelling on the hoof. “Back then there were so many regional airlines you could fly commercial every day,” says Perry. So we went right from station wagons to flying commercial. We never did the tour bus thing until the band got back together in ’84. So we kind of missed that whole riding around together in the same bus. Sometimes we were able to jump on a commercial plane after a gig, But mostly we’d get up the next day, run to the airport.

“People were starting to hear about the band, heard us on the radio. Older people still looked at rock’n’roll like it was devil music. But there was no hassle. Maybe someone would be like: ‘You play guitar, really?’ But no security, nothing, just ran onto the plane. A different time, man.”

You betcha.

The Get Your Wings: 50th Anniversary collection is available now.

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.