The narrative of 90s rock is carved in stone. The grunge scene, according to the media party line, swept away all that excess, culled all those cosseted dinosaurs with their gratuitous guitar solos, teased hair and ravaged septums. But that doesn’t quite square with the second coming of Aerosmith: a band whose sound and persona ticked all those boxes, and threw in songs about elevator sex and a mic stand bedecked with silk scarves for good measure.

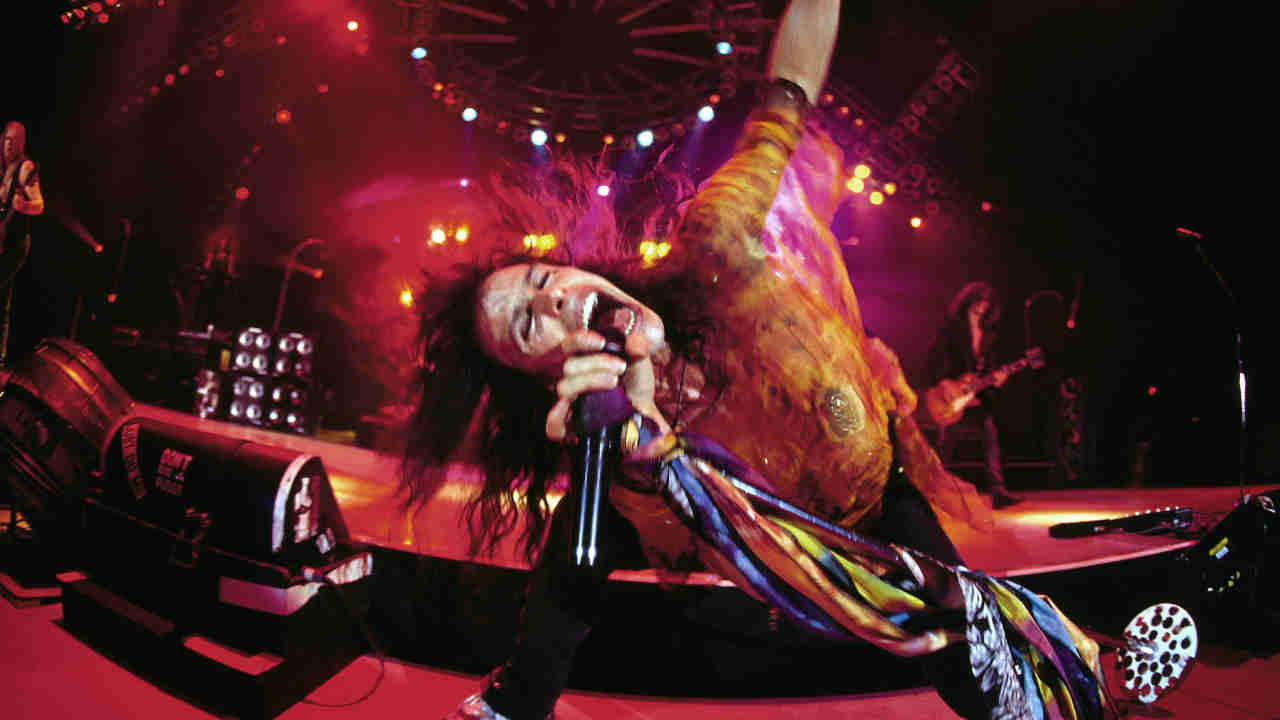

The Bostonians had indeed stumbled, but that was a lifetime before, in the newly sober and rudderless mid-80s. Stick a pin in the band’s imperious 90s run, by contrast, and you might have found them toasting back-to-back US No.1 albums, being inducted on Hollywood’s Rock Walk, sweeping the MTV and Grammy Awards, or finally reaching a crossover audience with their first and only US chart-topping single. As Steven Tyler beamed in one late-decade interview: “The last eight years have been what the first ten were supposed to be like. We climbed out of the ashes.”

Put the rebirth down to 1989’s Pump: the comeback special that gave Aerosmith their springboard into the new decade. A year later, in 1990, the fag-end of that album’s campaign was still burning, with single releases for What It Takes, The Other Side and Monkey On My Back. Meanwhile, the band’s label cashed in on what they probably assumed was a lucky blip, releasing 1991’s lavish Pandora’s Box compilation. That too went platinum, but there was a sense it was time to stop sweeping the vaults. “A patchy, expensive introduction to the newcomer,” griped Q magazine’s review, “and [it] falls irritatingly between the stools of rarities collection and definitive compilation.”

The decade’s first flash of creativity went down in early 1992 at LA’s A&M Studios, even if this initial attempt at what would become the Get A Grip album was aborted. “We decided the songs just didn’t jump,” noted Joe Perry, and the label agreed, with Geffen’s John Kalodner recalling that “when Steve, Joe and I sat and listened, I just felt they needed more variety.”

A scan of the Get A Grip credits reveals how the band fixed that issue, bussing in an army of guest songwriters that included Jim Vallance, Desmond Child, Taylor Rhodes, Richard Supa, Jack Blades, Tommy Shaw, Mark Hudson – and even Lenny Kravitz (on Line Up). “With Permanent Vacation,” reasoned Perry, “we found out after it was out, when we were on the road, that certain songs didn’t work for us. Because of these experiences, we did a lot of editing before Get A Grip came out, and that’s another reason we ended up pulling back and writing a bunch more songs.”

Tyler was sanguine, telling Rolling Stone in 1993 that they had hatched “a shitload of great stuff. We knew we had to make it the biggest, the baddest, the bravest and the scariest Aerosmith record yet.

“We got a grip on all the things that make us Aerosmith,” the singer trumpeted in the same interview. “We got a grip on all the things that sometimes get too refined along the way. We got a grip on what we’re all about. I mean, this stuff is something. This is rocksimus maximus.”

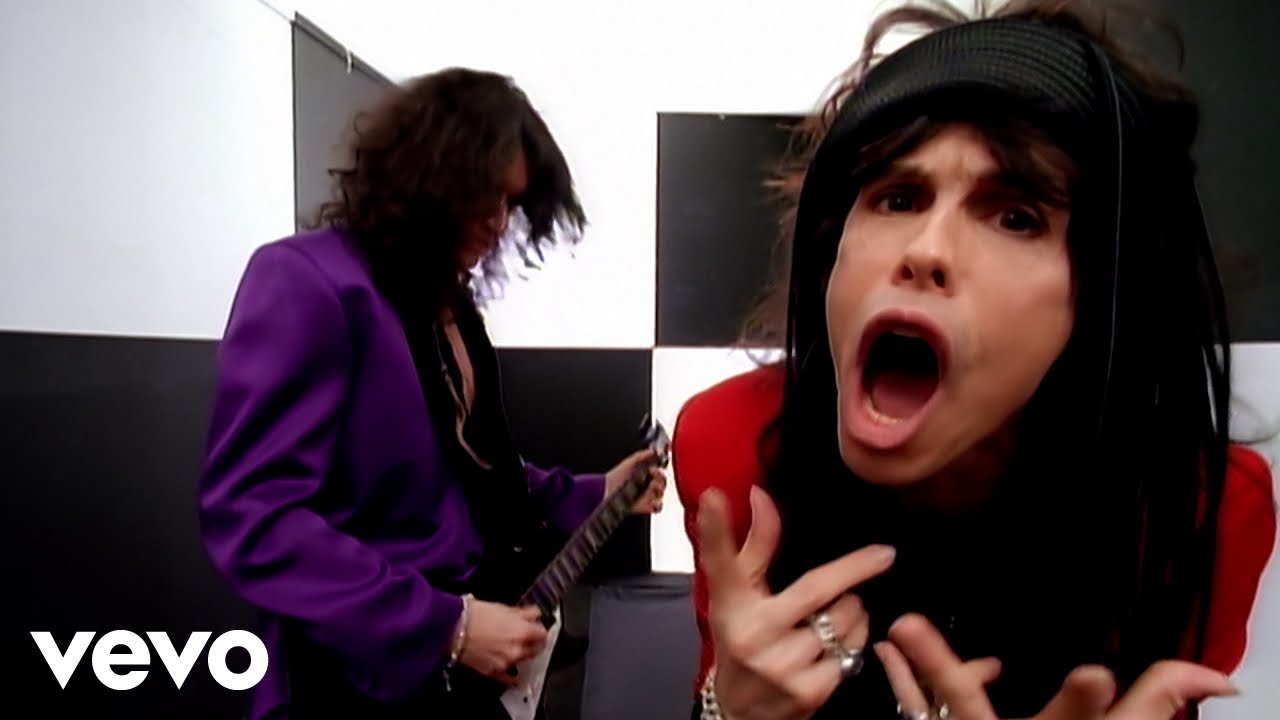

In retrospect, Get A Grip didn’t quite top Aerosmith’s 70s classics. But the highlights across these 14 tracks are undeniable, right from the neck-tingling moment that Intro’s tribal rap-rock breaks into the stinger riff and holler of Eat The Rich. Livin’ On The Edge was an arms-around-the-world soft-rock ballad, inspired by the 1992 Los Angeles race riots (the band would later order President Trump to stop using the song at rallies). Amazing and Cryin’ were an irresistible pair of power-ballads whose popularity would irk Perry in years to come (“I go, ‘I’m gonna go out to play fucking Cryin’ again?’”)

Elsewhere, Shut Up And Dance was a route-one crowd-pleaser, while the lighters-aloft Crazy came with a dubious rebel-schoolgirl video that saw actress Alicia Silverstone and Tyler’s own daughter, Liv, fling their shirts from a moving car. “If you only knew what it looked like originally,” said the singer. “It was total lesbian. I said, ‘That’s got to come out’.”

Conversely, Tyler pushed hard for the inclusion of the title track’s references to their former lives as junkies. “Some of the guys said: ‘I don’t think you should be singing, “The buzz that you be gettin’ from the crack don’t last/I’d rather be OD’in’ on the crack of her ass” – it’s too sexist’,” noted the singer of Fever. “And I said: ‘I’m not putting this album out until this song is on there. I put this down as a statement of where I’m at now, and that’s gotta go on this album.’”

Released in April 1993, Get A Grip did even better business than Pump, hitting No.1 in the US and No.2 in the UK (only pipped by Cliff Richard’s The Album in the latter). Ultimately, it would become Aerosmith’s best-selling global release, shifting some 20 million copies worldwide, even despite protests from animal rights activists (quelled when it was revealed the sleeve’s pierced udder was a digital creation). And if some critics flagged up a surfeit of ballads and external songwriters, most reviews saluted an album that continued the upward trajectory. “Nothing stands between the world’s greatest hard rock band,” wrote the hard-to-please music critic Robert Christgau, “and their best album since Rocks.”

That summer, taking the album out on a 16-month world tour, the band’s stock had never been higher. The one frustration, noted Perry, was that some of the new songs didn’t ignite the crowd. “We worked on [the song] Get A Grip out at Long View Studio in Western Massachusetts,” he told the Radio website. “I can remember staying up in the loft with Steven and we were working on some different things. We said, ‘This riff is gonna work. This has got it’. We named the record after it… we played it live and it just laid there flat. We discovered there were other songs people would rather hear.”

As 1994’s multi-platinum hits compilation Big Ones reminded the world, Aerosmith had plenty of those. But the band had one eye on the future, too, with that summer’s prescient CompuServe promotion letting fans download the track Head First from the Internet: an industry-first from an A-list band. With the primitive bandwidths of the time, the download process could take as long as 90 minutes, but that didn’t dissuade more than 10,000 fans from doing so during the two-week promotion. Warming to this nascent technology, by year’s end, the band had also embarked on the Cyberspace Tour ’94 that saw them conduct a series of one-hour online interviews. “If our fans are out there driving down that information superhighway,” reasoned Tyler, “then we want to be playing at the truck stop.”

But for now, at heart, Aerosmith were a major-label band operating within the traditional industry and enjoying all its trappings: a fact underlined by their new record deal with Sony, worth an estimated $30 million. The first release under this contract was originally intended to be a straight blues album. Tyler: “And then we caught wind that Clapton was doing it, and we went, ‘Fuck!’ It always happens.”

Instead, setting up in January 1996 at Miami’s Criteria Studios with producer Glen Ballard, Aerosmith embarked on what became Nine Lives, this twelfth album’s title referencing the band’s famous resilience (Perry: “It should have been called Nine Hundred Lives”). That resolve was about to be tested. Joey Kramer was struggling; having lost his father, the drummer plunged into a “big blue funk” and stepped away from the band, telling MTV, “I went into a deep depression. It was an emergency that came up for me and I had to take care of myself. That was the most important thing at the time.”

There were deeper problems in the guts of the band. Manager Tim Collins, it’s universally acknowledged, deserves huge credit for dragging the drug-addled line-up back into contention in the previous decade. But by the mid-’90s, it slowly dawned on the members that he was using divide-and-rule tactics. Kramer alleges his position was put under threat by Collins. “While I was away taking care of this problem,” the drummer told Mojo, “[Collins] lied to my partners. He told them the record company was putting pressure on to get the album done. This was not true. He was trying to get rid of me.”

Tyler accused Collins of even more damaging mind games in an Independent interview. “We were in Florida, on such a roll. There were beautiful girls and beautiful weather and ice-cream parlours. Then [Collins] started making up some nasty rumours – that I was back on heroin and the band were breaking up. He told the band a lot of things that I never said – that I wanted Tom [Hamilton, bass] thrown out and I wanted Joey thrown out. And they drank the Kool-Aid.”

“In the end he was pushing his doctrines on the band,” Tyler added in a Times interview. “Don’t get out of limousines with your wives at gala events, ’cos you’ll alienate your core fans. It was control issues. He went from being a really good facilitator and pilot of the Aerosmith ship, a conscious pilot to a Pontius Pilate. He went to Rolling Stone magazine and told them that I was still on drugs, and that he knew I was fucking women, just a whole barrage of things that no true friend or manager should do to their client.”

Collins had to go. And so did much of the early Nine Lives material, when the record label decided that Ballard’s multi-tracked production and the songs recorded with stand-in drummer Steve Ferrone “just didn’t have the Aerosmith kick-ass ability”. The sessions moved to New York, Kramer returned to the drumstool, and production duties were bestowed upon Kevin Shirley, whom Tyler noted “has got it somewhere stuck between Toys In The Attic and Rocks”.

In fact, Nine Lives had broader horizons than that. There were straightahead rockers, like the title track, written immediately after the band returned from watching AC/DC, and the horn-bolstered Falling In Love (Is Hard On The Knees). “The more you learn, the more you’re afraid to give up,” said Tyler of the latter’s lyric. “In the beginning you’ll fall for anything, if you don’t learn what to stand up to. Love can take you down. But it’s a strange world now. I’m not sure if I’m falling in love with more things, or just relying on the old things I love the most and trying to get back to them.”

But there were curveballs, too, like the louche, easy-rolling pop of Grammy-winning single Pink, and the sitar lines of the subcontinent-flavoured Taste Of India. “Nine Lives was different,” said Tyler on the Charlie Rose talk show. “In the sense that we hit upon a couple of East Indian vibe type-things that Yma Sumac and Donovan were into and the Stones and The Beatles. And it was something we’d never done together.”

That vibe spilled into Nine Lives’ original sleeve art, which featured a cat-headed Lord Krishna prancing on the coils of the snake god Kaliya (until objections from the Hindu community saw it replaced by a feline tied to a knife-thrower’s wheel).

Released in March 1997, Nine Lives was another big one, once again hitting No.1 in the US, and while the album didn’t sell in the same numbers as Get A Grip, many critics were impressed (“Aerosmith can be relied on,” wrote Rolling Stone, “to temper their puerile machismo with plenty of humor, heart and artistic ingenuity”). As for the lineup, they were just glad to have made it through. “At the end of Nine Lives, I wanted to quit the band after all the shit,” noted Tyler. “Now I want to do another record. The air is clearing.”

As it turned out, it would be another four years before Aerosmith returned with Just Push Play. But they still had one more ace to play out the decade. Directed by action supremo Michael Bay and starring Bruce Willis (and Liv Tyler), 1998’s Armageddon was a forgettable popcorn movie about a space mission to thwart an asteroid headed for Earth. But when songwriter Diane Warren offered Aerosmith her power-ballad, I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing, the band’s emotive reading outlived the film. “When I first heard it,” Kramer told Classic Rock, “it was just a demo with piano and singing. It was difficult to imagine what kind of touch Aerosmith could put on it and make it our own. As soon as we began playing it as a band, then it instantly became an Aerosmith song.”

“‘I could lie awake just to watch you sleep…’” mused Tyler of the song’s opening line. “I mean, how much in love with someone do you have to be to do that? But [Warren] nailed it. That’s one of the most precious opening lines of any song I’ve ever heard. And with a movie behind it, that’s like the Titanic coming into shore riding a five hundred-foot tidal wave.”

I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing would give the band their first and only US No.1 single, as well as an Academy Award nomination. But in 2002, Classic Rock’s Ian Fortnam wondered if the band might have preferred their big crossover moment to be a self-penned song. “Well, yeah,” considered Perry. “But, at the time, we just didn’t have the time to settle down and do it. We were out on the road, so they brought us in to see the movie and said ‘Here’s the song, this is where it fits into the movie, you can do it if you want’. We were in the studio within the next three days cutting it. And yeah, we do wish that we’d had a little more time, so that we could have had a shot at writing it, but it was perfect timing. The song was great, people loved it, and I don’t think people care that much who wrote it.”

I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing tied a bow on a decade that had been as close to an unmitigated success as it gets in the hazardous business of major-league rock ‘n’ roll. And yet, in July 1999, as the band watched the grand opening of the Rock ‘N’ Rollercoaster Starring Aerosmith at Walt Disney World in Florida, the symbolism might not have been lost on them. After scaling such unimaginable heights, one wrong move and there was an awfully long way to fall.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Aerosmith