The members of Aerosmith have had plenty of strange bedfellows in their 33 years together. They’ve kept company with all manner of drugs and drink, hot rods, women and weapons. There have been oddball sponsors, like Dodge Trucks. And unexpected companions like author Elmore Leonard, who took a liking to the group while writing his Get Shorty sequel Be Cool.

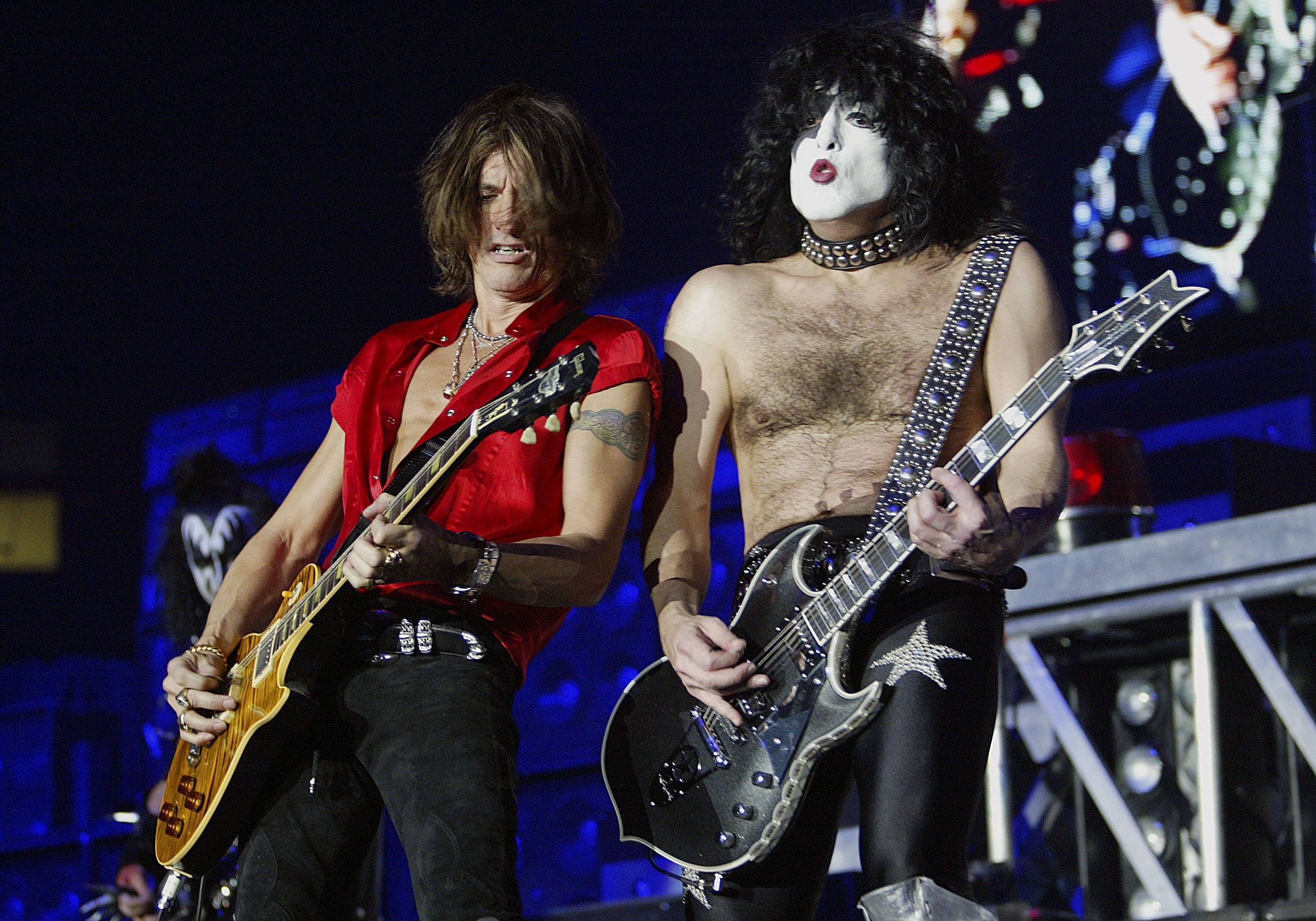

So in the great scheme of things, for Aerosmith, hitting the road with Kiss – which they did during the summer of 2003 in the US for a tour expected to last into 2004 – wasn’t a totally unlikely confederation.

“Well, we’ve been talking about going out with Kiss for a while,” says guitarist Joe Perry, who formed Aerosmith in 1970 in Sunapee, New Hampshire, with former Toxic Twin Steven Tyler and their mates, guitarist Brad Whitford, bassist Tom Hamilton and drummer Joey Kramer. “The last, probably, three years it’s come up as a possibility, and it was just one of those things – their schedule and our schedule, and the timing never worked out. This year it just happened to come together.”

It is not, however, the first time Aerosmith and Kiss have shared a stage – although it’s certainly been a long time. All concerned reckon it was 1974, when Kiss did a few shows opening for Aerosmith. And even though they were a couple of years behind the Boston rockers, the New York shock rockers had little trouble getting the headliners’ attention.

“We’d run into them before,” Perry recalls. “I think we ran into them at a party or something, and Tom remembers Ace [Frehley] being drunk in his hotel room and he just said: ‘I’m in this band Kiss…’. Then we were in New York somewhere, and this band went on before us called Kiss.”

Perry laughs as he remembers his first impression of Kiss: “We see these guys, and they’re wearing black leather jackets and all this make-up, and we’re all looking at each other going, ‘Jeez, we spent all this time learning how to play, and these guys are doing all this theatrical stuff. Is this where this is going?’. They knocked the audience out, and we had to follow them. It was pretty funny.”

But, not surprisingly, when the two bands later shared a bill in Detroit, Perry recalls: “There was a real sense of competition at that show ‘cos they were really hitting their stride then.”

The competition, of course, is past-tense these days, as the two bands divvy up the box-office grosses on the tour. It’s been replaced by mutual admiration, the kind of regard that only survivors of decades of rock’n’roll wars can share.

“Both bands very much like each other,” says Kiss’s famously long-tongued bassist Gene Simmons. “There’s definitely a kinship there. And the truth is, for nearly 30 years Aerosmith has managed, by hook or by crook, to stay alive and thrive. You can only respect that.”

The mutual respect is shared by Perry. But, he acknowledges, when he straps on a guitar the competitive juices still flow a bit. “Yeah, there’s always the X-factor of taking that horsey ride and kicking it a little harder,” he says. “That’s certainly going on. Aerosmith doesn’t lay down for anybody.”

Aerosmith have indeed been standing for nearly three-and-a-half decades – not always tall, but always on their feet, whether staggering or strutting. The group’s story is long and sordid enough to fill a weekend’s worth of Behind The Music episodes, replete with substance abuse, interpersonal politics, temporary band break-ups, business hassles and more. It also has plenty of triumphs, from the 70s parade of hits launched by albums such as Get Your Wings, Toys In The Attic and Rocks, to cleaned-up 80s multi-platinum blockbusters like _Pump _and Get A Grip, to the chart-topping success of the power ballad I Don’t Want to Miss A Thing (from the Armageddon film soundtrack).

Aerosmith were inducted into the Rock’N’Roll Hall Of Fame in 2001, and received an MTV Icon tribute from that satellite and cable music network. On the heels of the former honour, the band’s most recent studio album, 2001’s Just Push Play, debuted at No.2 on the Billboard chart in the US and added some more platinum to the quintet’s catalogue. It was also promoted with a surreal half-time appearance at that year’s Super Bowl, during which Aerosmith performed with teen pop stars Britney Spears and N*Sync and rapper Nelly.

“It was a goof, and it was a blast,” Tom Hamilton says. “I think a lot of our older fans were terrified we were going to go off and sing Britney Spears songs. But it was just fun. It wasn’t, like, a mall opening or anything, it was the Super Bowl.”

Aerosmith’s has clearly been a charmed and tortured existence – a tale they told in the frank and unsparing 1997 memoir Walk This Way. And Perry says that when all the details are stacked up, he and his bandmates still find themselves periodically shaking their heads over the fact that Aerosmith have survived their trials and tribulations, and that the band members are still rock’n’rolling into the sixth decade of their lives.

“We’re really anxious to see how far we can take it,” Perry (53 in 2003) explains. “It’s always a toss-up between this and finding something else to do in life, ‘cos this is so all-consuming. But I look around and there just aren’t any other bands from my generation doing what we’re doing. That’s why it’s so exciting.”

Bassist Tom Hamilton, 52, adds: “We’re very aware that we’re kind of doing a little pioneering here. Or maybe we’re just emotionally very unstable or something that we have this desperate hunger to do this in public.

“You do get up into your 40s or whatever, you have kids and stuff. Most of the people you meet when you take your kids to school have normal jobs, live regular day-to-day lives; society exerts a lot of pressure for people to live like that. So you have to resist that.

“Every day when I come up into my studio to play or try to do anything musically, I’m aware that in order to do this right, I’ve got to completely go against the norms of society. And I still get a lot of pleasure from that.”

Among the greatest pleasures Aerosmith now enjoy is having a greater degree of control over their music and their career than they ever have before. In the 70s the group were guided by powerful managers Steve Leber and David Krebs. Another strong manager, Tim Collins, got the group back on track in the mid-80s, ushering Perry and Whitford – who had both left the band briefly from 1979-84 – back into the fold, and employing rehabilitation therapies to cure both personal wounds and addictions.

And any number of producers – from Jack Douglas to Bruce Fairbairn to Kevin Shirley – have worked alongside Perry and Tyler in the recording studio. But gradually, Hamilton says, “we figured out that we’re adults now, and that we should be taking control of a lot of things ourselves.”

That happened with Just Push Play, which Perry and Tyler produced – along with fellow Boneyard Boys Mark Hudson and Marti Frederiksen, who also co-wrote some of the songs – and recorded mostly in the basement studio at Perry’s home outside Boston.

“It was great,” Hamilton recalls, “but sometimes I’d feel like I was imposing if I wanted to get a sandwich or something. I think we just worked out a really good way of having the respect of being at somebody’s house and letting it be the fun recording process too.”

Perry, however, says that wasn’t an issue. “The whole house was wide open,” he says. “We’d be pounding on the drums at 10 at night and the guitars would be booming through the house. My wife [Billie, whose picture graces one of his favourite guitars] is an artist. She loved having all the creativity going on there. The kids loved it. It was really exciting.”

And being in control, Perry adds, was the most fun of all. “At the very beginning, we started making it the way we would make any record,” he explains. “When Steven and I made the decision to take over we felt the stuff was strong enough that we didn’t need anybody else to come in. And we got the support of the other guys in the band.”

Hamilton says he suspects that Aerosmith’s label “kinda humoured us in the beginning. I think they said, ‘OK, let’s let the boys go off in their studio and maybe later on we’ll record the real album’. But things went well, and the record company heard the stuff and they loved it, so they gave us their blessing, which was great.”

Aerosmith got similar grace to pursue their latest project, too – a back-to-basics, blues-oriented album, tentatively titled Honkin’ On Bobo and due out in early 2004. Laden with covers, it is being mixed by co-producer Jack Douglas during the North American portion of Aerosmith’s tour with Kiss.

“We feel like the moment is perfect for us to go and start doing things the way we did when we first started, and maybe changed our creative process,” Hamilton says. “One way to do that is to go and just pick out the music that really excited us in the beginning and tap into it again.”

Perry adds that after years of slick, precise record making, he thinks “it was important for us to press the reset button. And part of the way to do that is to go back to your roots and explore them and use them as inspiration to write new stuff, or just go back and reinterpret some of the old stuff.

“It’s a process. Any artist does that; you go back. If you’re a painter you go back and look at some of the old masters that turned you on and got you interested in painting to start with. We felt like it was just time to get into a room and play and make a record of the band playing live.”

Honkin’ On Bobo featuees both originals and covers, the latter category including the Willie Dixon/Muddy Waters staple I’m Ready, Bo Diddley’s Roadrunner, Blind Willie McTell’s Broke Down Engine, Mississippi Fred McDowell’s Back Back Train, the chestnut Baby Please Don’t Go and Peter Green/Fleetwood Mac’s energetic shuffle Stop Messin’ Round – which Perry has sung in concert for several years.

“We must have had about a hundred or so songs that we were looking at,” says Brad Whitford, 51. “We listened to a lot of music and just picked out some ideas. And I think we figured that once we started working on [the covers], in that process we’d start to create some of our own ideas.”

But, Perry adds, the criteria for what would fit on _Honkin’ On Bobo _remained loose throughout the project: “Sometimes it’s a good lyric or a good melody or something that I felt Steven could really take a vocal and wrap himself around and elevate,” the guitarist explains. “Probably the broadest kind of criteria would be: can you imagine if Aerosmith played this?”

Perry says it also felt like the right time to renew Aerosmith’s association with Douglas, who produced the band’s 70s landmarks albums Toys In The Attic, Get Your Wings and Rocks.

“He’s been around the block with us,” Perry admits, “and so much of working with a producer is bringing in an influence and feeling comfortable that he’ll help make something out of nothing, fill the black space. Sometimes it isn’t about just being a good musician, it’s about a couple of personalities that clash and turning the tape recorder on while it’s going on.

“With Jack it’s great. You can’t bullshit him. He was there from the start. We explored some of our best and most creative years with him. He isn’t afraid to stand toe to toe with any one of us – and that’s hard to find these days.”

And there were clashes, Perry says.

“There were a few things we’d just go head to head on,” he recalls. “I can’t say anything specific now. I just know definitely that there were strong feelings on certain things, and you’ve got to stand your ground.”

One perk of the …Bobo sessions was the chance for Aerosmith to spend an afternoon working with rock’n’roll pioneer Johnnie Johnson, who played piano in Chuck Berry’s band.

Perry says: “I woke up one morning and read in the paper he was in town that day, playing a gig at the House Of Blues. I made a few quick phone calls, and sent a car for him, and before I knew it he was sitting in the basement of my house, behind a piano.

“He sat down and played, and we talked and he told some great stories about playing with Willie Dixon. And the whole time I’m like, ‘Holy shit – that’s fuckin’ Johnnie Johnson sitting in my basement, man!’.”

Perry does lament, however, that the prodigious sessions meant “there’s so many things that we ended up having to leave off.” But, he agrees, that only means that there may be more …Bobo in the offing for the band.

“It made me realise why the Rolling Stones do it so often,” Perry says. “It’s something we really haven’t done that much of, but the Stones have always done that. Their first three records were basically cover records, so they got a lot of it out of their system at the start. But over the years, you look at their records and they’ve always gone back and grabbed a few songs here and there. We never did that. We did a few, but not as regularly as they did. I definitely see us doing more of that from here on out.”

You can count on seeing Aerosmith doing even more touring in the future as well. The group have spent a chunk of every year since 2001 on the road, and Hamilton says it’s those live shows that enable Aerosmith to maintain the following that in turn gives the band the juice to do projects like …Bobo.

“If you can go out on stage and create a good impression, you can count on those people coming back,” he says. “That’s always been one of the truisms of music.

“But I think there’s even more of a spotlight on that now. The whole downloading/piracy issue is hurting people’s ability to make a living by putting out records. So if you want to make a living playing music you’re gonna have to be good live. That was the fact when we first started, really. It’s funny how it came back around.”

This was first published in Classic Rock issue 60.