There’s a titty bar in Pattaya, Thailand, called The Tahitian Queen. It’s a tiny, dimly lit venue with about 50 girls utilising five well-worn poles while being observed by a variety of sweaty, overweight, balding members of the mid-life crisis club.

The Tahitian Queen was established in 1973, and it looks like very little has changed in the intervening years. Most importantly, the selection of music is frozen in that era: you can leer lasciviously at an array of young Asian beauties gyrating lifelessly and out of sync to the beats of Creedence Clearwater, Bachman Turner Overdrive and Bob Seger.

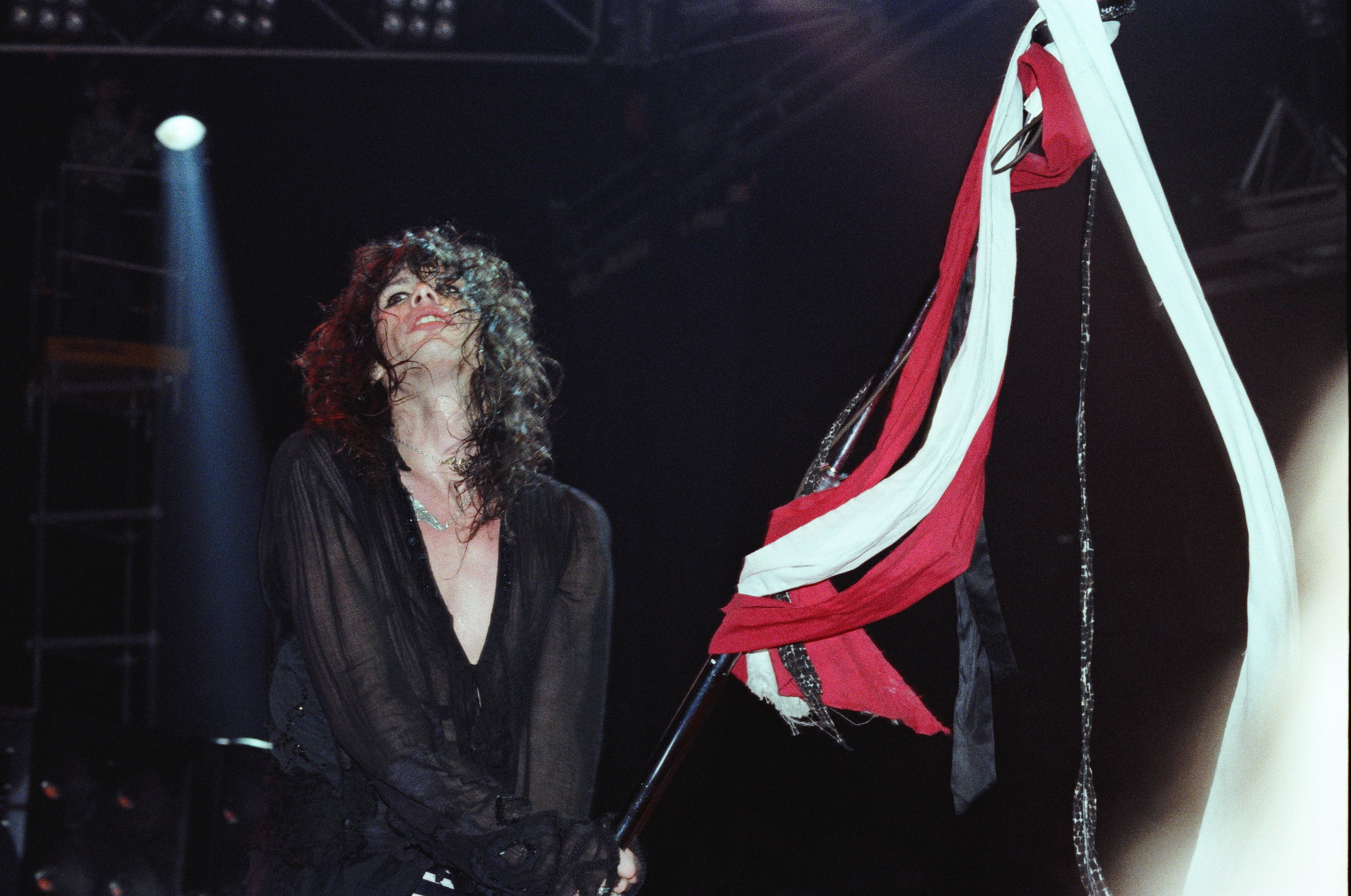

More to the point (in case you’re wondering about this self-indulgent diatribe about the Kingdom), if you find yourself ambling drunkenly into the unisex toilets – which conveniently face the ladies’ changing room – on the wall you will see the smiling visage of Steven Tyler looking down at you with an arm around an awestruck fan, presumably the club’s owner.

And even though it’s highly unlikely that a man of, ahem, Tyler’s stature ever set foot in such a low-rent establishment, everything about this place embodies the spirit and defiant swagger of Aerosmith.

It was the sleaze, the sass and the defiant ‘fuck you!’ attitude that Slash and millions of other post-60s teens identified with. Boston’s premier rock’n’roll merchants always delivered more than a lick and a promise and, as with my beloved Tahitian Queen, 1973 marked the beginning of an era that proved to be a defining point for the band’s roller-coaster career.

The Early Daze

“We weren’t too ambitious when we started out. We just wanted to be the biggest thing that ever walked the planet.” – Steven Tyler

It’s easy to reflect on the golden era of Aerosmith through rose-tinted specs. The reality is, that at the time the majority of the rock music press (myself included) hated them with a passion.

During those so-called glory days, Aerosmith were teetering on the edge of obscurity, bankruptcy and self-destruction. The years 1973 to 1976 created the DNA, the genetic imprint that made the band, almost destroyed them, and then – perhaps with some divine intervention – recreated them and sent them into a new stratosphere of success.

Here is my attempt to encapsulate the journey through the period that produced the four classic albums: Aerosmith, Get Your Wings, Toys In The Attic and Rocks. A ragged overview of a period in the band’s life where, for a brief moment, chemical excess and creativity seemed to be a working couple – the drugs did work!

Kids, do not try this at home…

Aerosmith (1973)

“Today I listen to these albums, some of our best, and all I hear is drugs.” – Steven Tyler

When Aerosmith started work on their first album in October 1972, they were already a solid live working band firmly established in their home town of Boston.

Signed to CBS records by the legendary Clive Davis (mentor to stars like Whitney Houston, Carlos Santana and Alicia Keys to name a few), the band picked producer Adrian Barber essentially because he was British. Aerosmith were keen Anglophiles, and although they were constantly being compared to The Rolling Stones, they were in fact more obsessed with the likes of The Yardbirds and Fleetwood Mac.

Not yet dented by the oncoming assault of the media, Aerosmith were still young and dumb enough to be able to confidently record their album fast, cheap and within budget.

“It took a couple of weeks to record, but we’d been playing the songs for a year,” Tyler recalled.

Barber, an experienced engineer who had worked with the likes of Cream and Vanilla Fudge, managed to come up with a workmanlike record. It lacked presence, and revealed the flaws of a band with very little studio experience.

Guitarist Joe Perry readily admitted that at this point, the band were very much in a formative stage: “You can hear how uptight we were, how little confidence we had. Steven even changed the sound of his voice on this album.”

Nevertheless, that debut did have some classic moments including Mama Kin and, of course, the original power-ballad Dream On – which always seemed to be a bone of contention with some members of the band, especially Perry, who felt Dream On went against what Aerosmith were all about. “I never thought Aerosmith should do ballads at all,” he said. “My philosophy was, the only thing a hard rock band should play slow was a slow blues.”

Eventually a chart-topper, it would be a couple of years before Dream On would be a meal ticket for the band, and in the meantime they were about to encounter some lean times. The record sold poorly and the record company weren’t exactly forthcoming with their support.

Tyler: “We played the album to the CBS top honcho. He looked at us and said: ‘There’s no single’. That’s when my heart sank. Nobody gave a fuck.”

In response to this apathy, Aerosmith resorted to what they knew best and hit the road on a tour that seemed to carry on for the next three years.

As they garnered a steady, solid base of fans, news came through that the record label were planning to drop them. The show was almost over before it had begun as the band’s former manager, Frank Connelly, an old-school gangster, recalled: “The record company had lost faith in the band because Aerosmith was the antithesis of what CBS was, a company that Clive Davis had built on Barbra Streisand and Paul Simon.”

Fortunately the release of Dream On as a single was met with enough of a positive response that CBS extended their option. As soon as the band came off the road they started work on their second album.

Get Your Wings (1974)

“The songs we write aren’t the kind that you can come out and fucking genuflect. We play kick-ass music.” – Steven Tyler

There were two major factors for the marked improvement in Aerosmith’s second album. First, the constant touring; the band had been writing material while on the road. Second, and more important, was the introduction of producer Jack Douglas. Already seasoned veterans of the slings and arrows of a vitriolic press and the general inertia of CBS, Aerosmith had become an insular unit, a musical street-gang who didn’t suffer fools gladly, but they seemed to warm to Douglas’s grizzled presence. He was a fine musician, an experienced producer, and had already seen the band live and recognised their potential.

Douglas recalls: “The band came on in stage clothes – very glam but still very street. I’d seen the Jimmy Page Yardbirds, and that night I thought I saw the American Yardbirds – not a copy, not an imitation, but the real thing. A hard-rocking blues, R&B rock group. I’m thinking to myself, ‘this is a great American rock band!’”

From the very first meeting between Aerosmith and Douglas, a mutual fan club was born. “Jack Douglas is a cool guy,” Perry announced. “We all like him personally. He has that New York edge. We’ve worked with a lot of people and never had the same feeling about anybody else.”

Douglas then proceeded to take the band to a new level of professionalism. He stuck them in New York’s legendary Record Plant studios and worked them hard until they became a disciplined unit.

The end result was a marked improvement on the debut. And although Get Your Wings didn’t set the world alight, it certainly created a template for the shape of things to come. Songs like Same Old Song And Dance and Lord Of The Thighs introduced Tyler’s talents for streetwise lyrics and playful innuendos, while the band’s interpretation of Train Kept A-Rollin’ gave a discreet nod to their mentors while at the same brashly announced their arrival as the heirs to a vacant throne.

As Douglas explained: “Tiny Bradshaw wrote and recorded* Train…* in the 40s, The Rock And Roll Trio had a hit with it in the 50s, and The Yardbirds owned it in the 60s. Now Aerosmith had taken it over and wanted to show how it should be done.”

Same Old Song And Dance was released as a single, and although not a hit, it got impressive airplay. The album peaked at No.100 and stayed in the US chart for a year.

Aerosmith also gained their famous ‘wing’ logo and a strong visual image. Some say that image was purloined from their management’s other doomed act, The New York Dolls, of whom Perry was an avid fan. He once revealed that: “People ask me about Guns N’ Roses, I tell them to go and listen to the Dolls.”

Aerosmith went back on the road brimming with a new-found confidence. The critics had yet to be seduced by their charms, but their opinions were becoming less disparaging; the radio stations began responding to the demands of the band’s ever-growing fanbase.

When Aerosmith released their next album, everybody would sit up and listen.

Toys In The Attic (1975)

“Aerosmith is as good as coming in your pants at a drive-in at age 12 with your little sister’s babysitter calling the action.” – Creem magazine

The quality of Aerosmith’s albums improved as the Tyler-Perry songwriting team strengthened and matured. Toys In The Attic was testament to this fact. While the first two records had only a handful of memorable tunes, ‘Toys…’ ably demonstrated that the punishing tour schedules and studio experience were beginning to pay off.

As Douglas saw it: “Aerosmith was a different band when we started the third album. They’d been playing Get Your Wings on the road for a year and had become better players… different players.”

Protected by a wall of powerful management and a viciously loyal road crew, the cracks were beginning to show in Aerosmith’s infrastructure. On the road ‘tantrums and tiaras’ were a regular occurrence.

By now, both Tyler and Perry were veterans of the needle; in fact Perry’s mother was so concerned about her son’s deteriorating health she moved to another state to avoid witnessing his decline.

Somehow this didn’t affect the quality of the music, as Perry recalled: “When we started to make Toys In the Attic our confidence was built up from constant touring. I don’t feel great about saying it was the drugs, but the plain truth is we were beginning to make money and we could afford better dope.”

Like its predecessors, Toys… did include a cover (Big Ten Inch Record) and a Chain Reaction song (You See Me Crying), but the remaining material was much more than mere padding. There were also songs from guitarist Brad Whitford (Round And Round) and bassist Tom Hamilton (Sweet Emotion). One of the highlights was of course Walk This Way, which, years later, and via a canny partnership with Run DMC, would catapult the band into a new era. Listening to the album, it’s difficult to believe that Tyler was experiencing a severe case of writer’s block (which would become a regular occurrence).

“I was going through hell all this time, trying to write the lyrics,” Tyler remembers. “Most of the time the whole idea overwhelmed me and I always put it off till the last minute. Now I had to write new stuff; no one else wrote the lyrics.”

Upon its release, the album went straight to the top of the US chart and went on to sell millions. Dream On was re-released and became their first Top 10 single – and their national anthem.

Yet Aerosmith were still only popular in certain areas of the US. They were also being constantly mauled by the ‘serious’ press, which gave Perry serious doubts. As he divulged: “Oftentimes I wonder if I am doing it right, if I’m actually contributing. Are we doing something good, or are we just followers?”

His questions were answered with a resounding affirmative with the release of the next album.

Rocks (1976)

“We were the garage band that made it really big – the ultimate party band.” – Joe Perry

‘Rocks’ is the album where it all came together, the time when the alchemy really worked. By now Aerosmith had hit their stride. The constant touring had transformed them into one of America’s top-grossing live acts with an insanely devoted following known as The Blue Army.

Up until now it had all been foreplay, but now the band really had to deliver the climax – and Rocks was the ultimate musical money shot.

As Douglas pointed out, “This was the big album for Aerosmith. It had to make a big statement about how loud and hard they were, and how unapologetic they felt about being who they were: this brash, rude, sexual, hard-core band.”

Every track is a masterpiece. Kicking off with the opening salvo of Back In The Saddle – the band’s musical statement of purpose – it displays Aerosmith at their peak. It became a commercial blockbuster, going platinum on release. Seemingly Aerosmith couldn’t get any higher. Although they had a bloody good go at it.

“We got good drugs because we could afford it, “ Perry admits. “All the big dealers started hanging around, so we only got the best stuff. We found a good, steady connection. At least until our guy in New York got murdered.”

Again the lyrics proved to be elusive. At one time the album was going to be called Aerosmith 5 in honour of all the unused instrumental tracks recorded while waiting for Tyler’s contributions.

Miraculously, it all came together. With Tyler and Perry getting lost in their collective chemical excesses and rock star grandiosity, the rest of the band came to the fore. And of course there was the other ‘honorary’ member, Jack Douglas. ‘Rocks’ is a testament to Douglas’s genius at pulling things together.

As Brad Whitford puts it: “The thing about Jack was that he was there, living with us in Boston, working, playing drums, pushing us in a good way. He’d try anything, and it inspired us. He was a mad genius, but so solid.”

In retrospect it’s difficult to see how things could get any better – you can almost smell a demise a-comin’. Punk was around the corner, and as far as Aerosmith were concerned, the ego had crash-landed. And while there’s no doubt they had delivered the goods in the studio, on stage they were beginning to disintegrate.

It would be a couple of years before it would fully fall apart, it was all starting to go a little pear-shaped.

“We played a show at The Forum, and in the middle I just stopped dead and looked out at 18,000 kids and didn’t even know where I was. I could sense danger and chaos,” Tyler recollects.

In their formative years the rock-scribe cognoscenti hated Aerosmith because they sounded and looked like the peers they worshipped. Ironically, in some quarters they are now reviled because of their mainstream success and partiality to soundtrack-friendly power ballads. But there are differences.

Nowadays Aerosmith don’t give a shit about the press and focus their energies on pleasing themselves and the fans who put them in their exalted position.

Meanwhile, I’m temporarily barred from setting foot in Pattaya (it’s for my own protection, apparently). And if the owner of the Tahitian Queen happens to read this, it was my Scots pal Kenny who stole the picture from the toilets, and I promise it will be returned on our next visit.

Which will be soon.