To witness Brittany Howard on stage is, frankly, little short of astonishing. Tonight she and her band, Alabama Shakes, are slaying them at Gloria’s, a 50s cinema-cum-theatre in the heart of Cologne. The place is rammed with heaving bodies, full to its near-1,000 capacity, the audience transfixed by the animated woman out front.

Wearing pink floral dress, and with a blue Gibson SG slung over her shoulder, Howard is roaring and shaking her way through a set of songs that sound like the most feverish, guitar-heavy rock’n’soul you’ve ever heard. Her bandmates are great players, too, but it’s noticeable that they stand a few discreet steps behind. Howard is clearly the star attraction here, a force of nature and an extraordinary presence.

Howard the live phenomenon may seem like the most natural thing in Christendom, but she insists it wasn’t always so.

“I was really nervous the first time I went on stage,” she explains earlier, sitting backstage prior to soundcheck, picking at a plate of salad with one hand and holding a beer in the other. “It all went by really quickly. But I was also fearless. My attitude was, ‘Right, here’s your chance. If you hold back, then you’re going to regret it. Just go for it.’ And that’s what I’ve always done.”

Both Howard and Alabama Shakes have come a long way in a very short time. Four years ago they were complete unknowns, playing weekend gigs at places such as Brick Deli & Tavern in downtown Decatur, just south of their home town of Athens, Alabama (population 24,000). All four members, holding down day jobs that they didn’t much care for, spent the rest of the time either rehearsing or driving up to Nashville to record the songs that would eventually surface on their debut album, Boys & Girls. This invariably meant a 100-mile overnight trip home, getting there just in time for work the next morning.

Such dedication isn’t completely unique, of course, but it is rare. “A lot of what’s happened to us came about just through the will to want to be in a band,” Howard states. “That’s the difference between Alabama Shakes and all the other bands I’ve played in – everybody has the drive to want to get better. I never wanted to do anything else, I always just wanted to do this.”

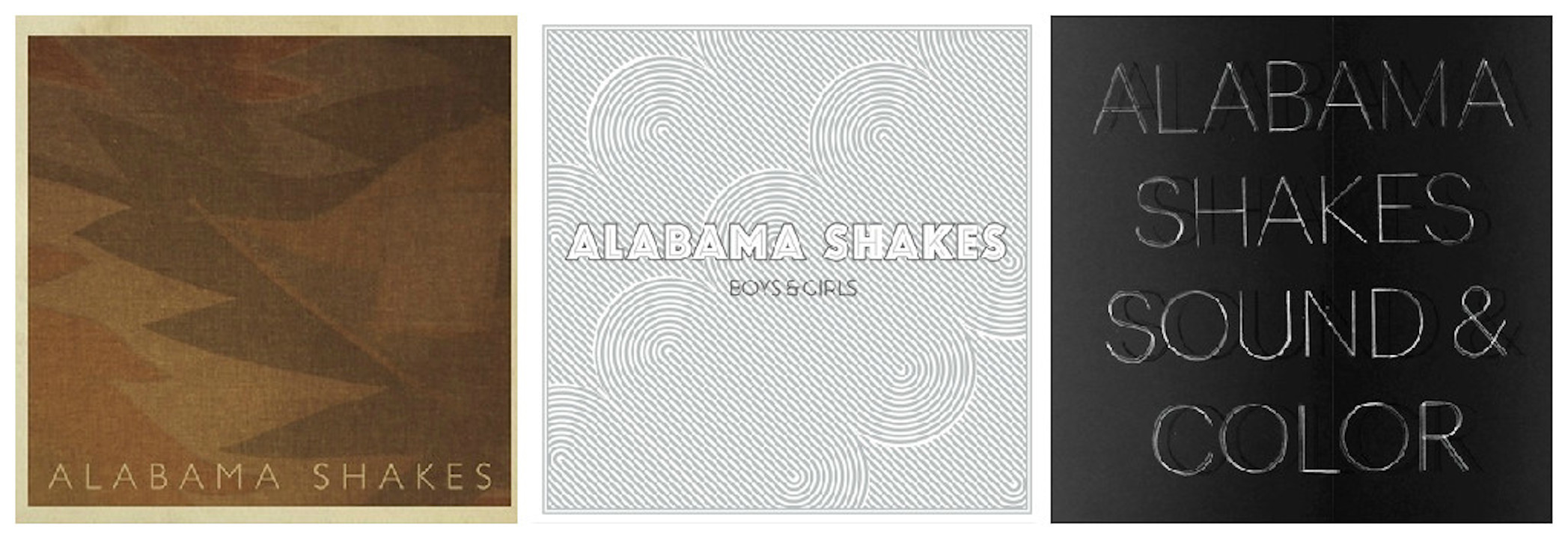

Boys & Girls was released in April 2012. A mighty rush of exquisite garage-soul, marked by limber rhythms and the kind of unfixed guitar licks that might have come from any point on the compass between the Bowery and the bayou, the album was a huge hit in both Britain and the US. It went on to receive three Grammy nominations and to date has sold more than three-quarters of a million copies. The lyrics of lead-off single Hold On – a raw, luminous soul stirrer with a killer vocal and waspish riff – suggested that the band’s sudden success was a victory for dogged perseverance as much as anything else. ‘Didn’t think I’d make it to twenty-two years old,’ Howard sings, in typically persuasive style. ‘There must be someone up above, sayin’ come on, Brittany/You got to come on up, you got to hold on.’

Alabama Shakes’ latest album, Sound & Color, released this spring, is another leap forward entirely. It’s also likely to outdo its predecessor at any moment, given that it sold nearly 100,000 units in its first week and went straight to the top of the Billboard chart. “Our whole worlds have changed in the last few years,” Howard marvels. “Everything is so different.”

There’s a tendency to peg Alabama Shakes as a southern soul sensation, especially in light of their relative proximity to Muscle Shoals, and the fact that their home state gave the world such soul legends as Wilson Pickett, Eddie Floyd and Percy Sledge. But that would be missing the point altogether. If there’s one common denominator in each member of the Shakes’ musical inclinations, at least in their formative days, it’s rock. Preferably the loud kind.

Howard and bassist Zac Cockrell – a man with so much facial hair that you fear he’s in danger of being overgrown completely – bonded at high school over a mutual love of The Ramones, Led Zeppelin and AC/DC. Their first impulse was to learn how to play some of the songs. Howard began running twice-weekly jams at her great-grandparents’ house. Her downtime was spent analysing the way Bon Scott held an audience’s attention on stage.

“I had this rock’n’roll DVD, 50 Years Of Rock’n’Roll, and it had about four discs of AC/DC live,” she recalls. “I thought Bon Scott was a hell of a frontman, because he was so engaging. He didn’t care what anybody thought. He’d arrive on stage dressed like a woman, with lipstick all over his face, but it wasn’t just showy. He was bringing it, that’s the thing. He had real talent.”

Drummer Steve Johnson, a friend of Cockrell’s who remembered hearing Howard sing at a party some years earlier, started turning up at the jam sessions in 2009.

“When I was younger I was into Alice In Chains, Soundgarden, Tool, Nine Inch Nails, those kinds of bands,” he explains, taking time out from prepping for Classic Rock’s photographer at Gloria’s. “My dad was influenced by people like Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Yes. So rock was very much my thing before this band. Then I discovered soul and R&B. I was introduced later to stuff like Funkadelic, who were rock, but with a real groove.”

The trio set about rehearsing and making demos. Guitarist Heath Fogg, four years above Howard at high school, had returned to Athens after attending the University of Alabama. Now he was painting houses to finance gigs with his own band, Tuco’s Pistol. Unbeknown to him, however, he’d already played a crucial role in Howard’s musical education, back in 2000.

“I went to my first live show when I was eleven,” Howard says, “and Heath was actually playing in the band. They were all kids who went to our school, and I had no idea they could play. I remember going: ‘This is amazing! I want to do that. If they can do it, so can I.’”

Fogg invited the trio to open for Tuco’s Pistol at the Brick Deli. Staggered by what he saw, after the gig he immediately cast in his lot with the Shakes.

“Things started happening when Heath joined, because he had ambition and drive,” says Howard. “We all felt that we could do something with this band. In the beginning when we played we did all kinds of strange covers; we’d do the James Gang’s Funk No.49, AC/DC’s Let There Be Rock and Fairies Wear Boots by Black Sabbath. Then we’d do Loretta Lynn and switch it up to James Brown. So we’d be doing gigs, and all these people would be staring at us: ‘Why the hell is this band playing Let There Be Rock?’ Then I’d take that solo, which I learned note for note, and they’re like: ‘What the fuck is this?!’”

Merrily cranking out covers is all well and good. But the real turning point came when they started writing their own songs. Howard poured her hopes and frustrations into lyrics that were abstract enough to be something other than straight autobiography. The band as a whole, meanwhile, began writing music that sounded like a southern refraction of their rock’n’roll instincts. “There wasn’t any one type of vision,” Howard says, “it was a case of let’s try to write songs together and see what comes out.”

This was a natural process, it seems, governed by intuitive grooves and driven by one of the most electrifying vocalists of this, or any, age.

“There are many chapters to that,” contends Johnson. “I feel like Brittany’s voice developed from when I first met her until a few years later, when she’d graduated from school. I do remember getting together after that time lapse, hearing her voice and thinking that this is really good. If you’re a musician and you’ve played in bands, you come to a point where you realise that the vocalist is the hardest position to fill. It’s not just about having a good voice, it’s about charisma and talent and showmanship, all these things you can wrap it into. Some people are real strong on one side and lacking in others. But Brittany had it all.”

The Shakes’ fortunes took an abrupt upturn in the summer of 2011, when LA music blogger Justin Gage, intrigued by a photo of Howard in full flight, posted You Ain’t Alone on his Aquarium Drunkard site. The following morning the band found themselves flooded with offers from various labels and managers. Gage also took the step of emailing Patterson Hood, leader of fellow Alabamians Drive-By Truckers. His interest sufficiently piqued, Hood and his management team fetched up at the Shakes’ next gig, at a local record store. He was floored by what he saw. What struck him instantly, he said later, was that despite being comparatively unschooled, their sound was already fully formed.

Rechristening themselves Alabama Shakes, the band released a self-titled EP that September. This, along with an industry showcase gig in New York, swiftly led to a deal with ATO Records, home of Drive-By Truckers. Then things started to accelerate, beginning with the release of Boys & Girls seven months later.

The band’s gruelling tour schedule meant that they were unable to work on a follow-up until the back end of 2013. This time, despite their debut’s near blanket approval, they were determined to make exactly the kind of record they wanted to.

“Based on Boys & Girls, there was a very strong impression from everybody that we were going to be a southern rock, gospel-influenced soul band,” Johnson says, responding to some critics who dismissed Alabama Shakes as a retro outfit. “But there are so many different styles and players that we’re into, that we pick and pull from influence-wise. It goes back to development and time and practice. We have a lot of interests, it doesn’t just stop at southern rock.”

Sound & Color certainly introduced an extra dimension to Alabama Shakes’ sound. It’s still undeniably the work of the same band that made Boys & Girls, with its mongrel hybrid of raucous garage rock and cleansing deep soul, but it’s also a many layered expression of their restless ambition. Songs such as Guess Who carry the imprint of Superfly-era Curtis Mayfield; the strikingly different Gemini is a psychedelic spacescape; the strutting Don’t Wanna Fight is minimalist funk; The Greatest is a gleeful blast of ratty punk that burns away the distance between the Brick Deli and CBGB. Other touchstones are less explicit but equally vital.

“I was listening to satellite radio one night, flipping channels, and heard these really cool drums,” Howard recalls. “So I hung in there, and I’m like: ‘This is the shit!’ It turned out to be Holy Thursday by David Axelrod, which gets really intense at the end. Everything about it was so up my alley. All of us are really into tones, because in my opinion tones can evoke something in you. Some of those records – Axelrod, Curtis Mayfield, Miles Davis – speak to you on so many different levels. It’s about putting so much thought into how everything interacts and how integral everything is to the completion of this entire song structure. It’s like being able to look in an almost omnipresent way; you see every direction of the song. We wanted to make an album that showed off our abilities and stretched us a little further from what we might usually play.”

One of the most fascinating things about Alabama Shakes is their creative dynamic. It’s too easy – and plain wrong, in fact – to conclude that this is Howard’s band, that she calls the shots and brings the others into line. In fact they’re four distinct, disparate people, each with their own notion about how to get the best out of themself.

Cockrell, for example, is so laid-back he’s almost horizontal, though it’s noticeable that he’s the most voluble member of the group during soundcheck. He makes a number of suggestions, subtle changes in tempo and detail, and the others duly comply. Fogg is similarly understated off stage, but it’s apparent that the rest of the band look to him as a barometer of their sound when they hit on a groove. There’s a lot more going on here – the sort of low-key exchanges peculiar to a group of people who’ve spent a lot of time in each other’s company – than meets the casual eye.

“We’re all pretty original characters and strong personalities,” says Johnson. “Everybody’s really grounded, down to earth, humble. But I can also be very opinionated, and don’t have a problem saying it. And when you get on stage those things are sometimes amplified. Zac’s really chilled and in his pocket. Heath’s the same way. I may look like I’m chilled, but on the inside I’m usually going nuts.”

“This band is a huge democracy,” Howard adds. “If one of us doesn’t like something, it’s probably for a good reason. Each of us trusts everybody’s else’s tastes.”

Observing Howard in action, it’s plain to see why so few other bands reach the parts that Alabama Shakes do. Quite simply, it’s because they can’t. Howard’s intensity on stage is such that you sometimes worry for her, as if prolonged immersion in the depths of these songs may somehow be harmful to her well-being. There are times when her anguish seems very real. On Your Way, for example, one of four tunes in tonight’s encore, is about her elder sister Jaime, who died of cancer when Brittany was nine or ten. ‘It wasn’t me/Why wasn’t it me?’ she sings, the sorrowful tone of injustice all too palpable.

There are plenty of other guitar bands out there, even ones who, like Alabama Shakes, have grasped the idea that musical malleability may be central to having a lasting career, although none of them have Brittany Howard. And while she struggles to explain what it is about being on stage that makes her so fervent, she does admit that it involves a kind of unspoken communion. “The audience has this energy. And I’m a sensitive person, so you pick up on it,” she offers. “Not everybody dances, but you can see the expression on their faces and they’re all nailed onto you. They’re really into it and they’re just hopeful, I guess. It’s something that you can just feel.”

If Alabama Shakes’ relentless touring is inching them closer to burnout, they’re showing few symptoms. Indeed the impression they give off is one of take-it-as-it-comes contentment. “My whole goal through the entirety of high school was to find a band,” says Howard. “And it took me a lot of time to find people who were willing to give everything for that. I was just trying to get this music thing to work. All my passion went into this, and it had to be for a good reason. It’s just that I never really knew how it would turn out.”