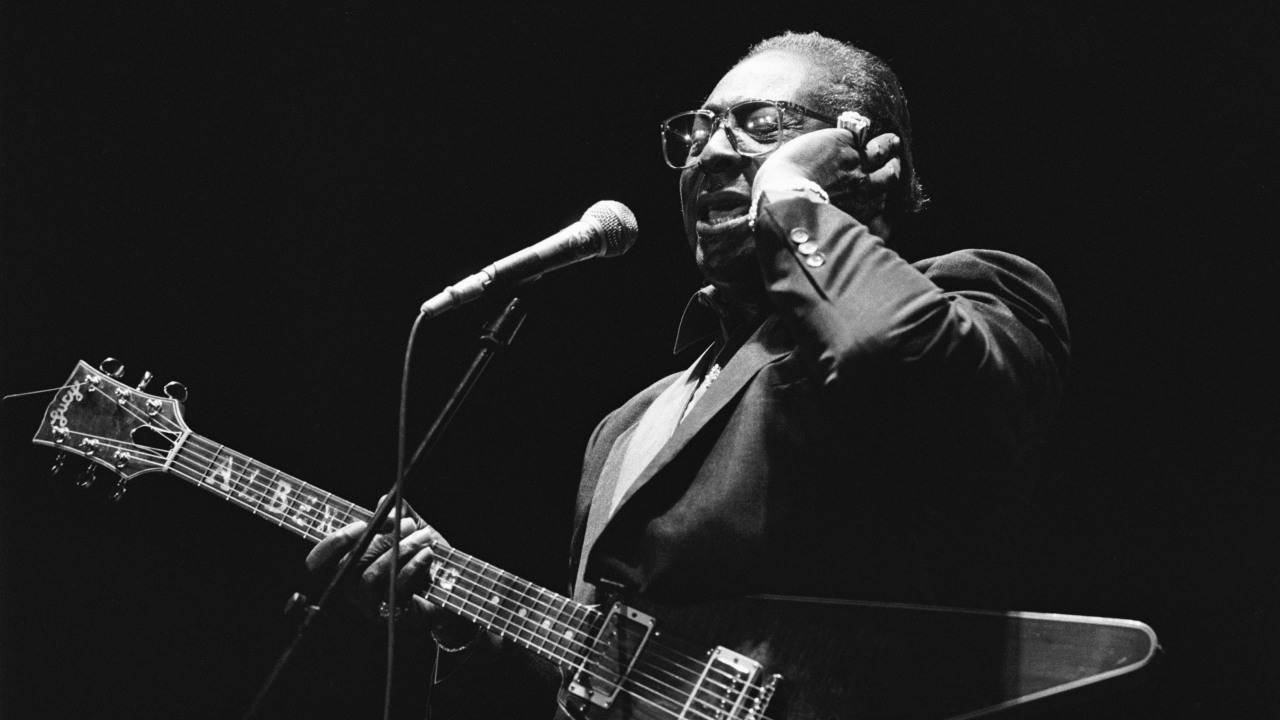

Albert King had already enjoyed a decent-sized hit before his 6ft 4in, 250-pound frame cast a shadow over the threshold of Stax Records at 926 East McLemore Avenue in South Memphis in 1966.

But that had been a long five years before, when his Bobbin Records release Don’t Throw Your Love On Me So Strong peaked at No.14 on the US Billboard R&B chart. If Albert had dared to think that this glimpse of success meant his years of slogging around seedy dives and juke joints and cutting deadbeat 45s were over, he was sadly mistaken. His subsequent Bobbin releases went the way of the dinosaurs and he faced a future likely no more promising than countless other grafting musicians on the tough Chitlin’ Circuit in the Deep South.

Albert desperately needed someone to throw him a bone. It fell to Stax Records co-founder Estelle Axton [the ‘Ax’ in Stax] to do the honours. When Albert sauntered into the Satellite Records shop that was slotted into the foyer of the Stax building, Estelle recognised Albert as an artist she had occasionally stocked in her record racks. After some ‘getting to know you’ chit chat, the conversation turned to the possibility of Albert recording at Stax. “I said, ‘Well, it’s gonna take a lot of convincing,’” Axton told Rob Bowman for his definitive book, _Soulsville USA: The Story Of _Stax Records, “‘because we’re doing R&B. We’re not doing blues. But the first thing they’re gonna tell you is, if you’ve got a song, they’ll listen to you.’ ‘It just so happens I’ve got one.’ So I let him hear Laundromat Blues.”

As the custodian of the Satellite Records shop, Estelle would often suggest songs – 45s that hadn’t yet attracted mass attention – that she thought would be good for a particular Stax artist to cut. Laundromat Blues, composed by a songwriter from Indiana called Sandy Jones, would soon by cut as Albert King’s first 45 for the Stax label (catalogue number 190). It was eventually track-listed on an album that not only changed Albert’s life and fortunes, but which would see him hook up with the world’s greatest soul band, Booker T. & The M.G.’s, and redefine the sound of blues. The impact of the album’s release was keenly felt as far away as London, where Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix became obsessed with aping the guitar playing and grooves they heard on a slice of divine vinyl, this album called Born Under A Bad Sign.

Albert was in at Stax then. But it had been a hell of a journey to get there. The man who would be King was born Albert Nelson on a cotton plantation in Indianola, Mississippi on April 25, 1923. Well, that’s what he claimed. There’s no real evidence that he was born anywhere near the place. Why would he lie? Well, B.B. King was born just outside Indianola on a patch of land called Itta Bena on September 16, 1925. As Albert would eventually adopt B.B.’s surname and had once claimed to be his half-brother, which turned out not to be true, it’s possible he wanted to cement his imagined kinship with his fellow bluesman still further. It’s just as feasible that poor record keeping by the local government was to blame and Albert did indeed run the same streets that B.B. first busked on when he was a teenager.

What we do know is that Albert and his 12 siblings settled near the cotton plantations of Forrest City, Arkansas, when he turned eight years old. Like most African-American kids of the day, he initially found his voice singing gospel in his local church, performing with the other Nelson kids and his guitar-playing father.

After trying his luck with local bands, Albert, now in his 20s, moved briefly to Gary, Indiana, before taking off for Chicago in 1953. It was at this point that he cut his first single, for Parrot Records. Founded in 1952 by the disc jockey Al Benson, the Parrot Records label only lasted until 1956 but in that brief period released a series of sides by the likes of Coleman Hawkins and his Orchestra, J. B. Lenoir, Snooky Prior, Lowell Fulson and Orchestra, and jazz pioneer Ahmad Jamal. Some of these recordings would later be released by Chess Records. Albert’s single Parrot release, Be On Your Merry Way/Bad Luck Blues (catalogue number 798), shifted a few units but was not a big enough success to commit Parrot to a follow-up, and certainly not a contract.

It was sometime around this period that Albert began using the surname ‘King’, apparently inspired by the commercial success of B.B.’s breakthrough 1952 single, 3 O’Clock Blues. In a further parallel, he would christen his ’58 Gibson Flying V guitar ‘Lucy’, not so far removed from B.B.’s six-string tag, ‘Lucille’. “You’d have to ask B.B.,” he commented in the 80s. “Mine was named Lucy first.”

After his experiences in Chicago, Albert was on the move again, landing in St. Louis in 1956 where he assembled a band. In 1959, he began cutting sides for Bobbin Records, kicking off with Why Are You So Mean To Me/Ooh-Ee Baby (Bobbin 114). This was followed by Need You By My Side/The Time Has Come (Bobbin 119) and Blues At Sunrise/Let’s Have A Natural Ball! (Bobbin 126) in 1960; and I Walked All Night Long/I’ve Made Nights By Myself (Bobbin 129), Travelin’ To California/Dyna-Flow (Bobbin 130) and Don’t Throw Your Love On Me So Strong/This Morning (Bobbin 131) in 1961. It was this latter aforementioned release, also licensed by the King label in the same year, that had proved his biggest success up to that point in his career.

Unfortunately, once the excitement died down, and three subsequent 45s for Bobbin (and a couple for the Coun-Tree label) failed to fan any embers generated by Don’t Throw Your Love On Me So Strong, Albert was back playing small clubs and southern dives, the title of that old Parrot Records side, Bad Luck Blues, ringing in his ears. Just like any road-weary blues artist, he was ready to accept any good luck that was going – and that’s exactly what he found that day he bumped in Estelle Axton at the Satellite Record shop at Stax.

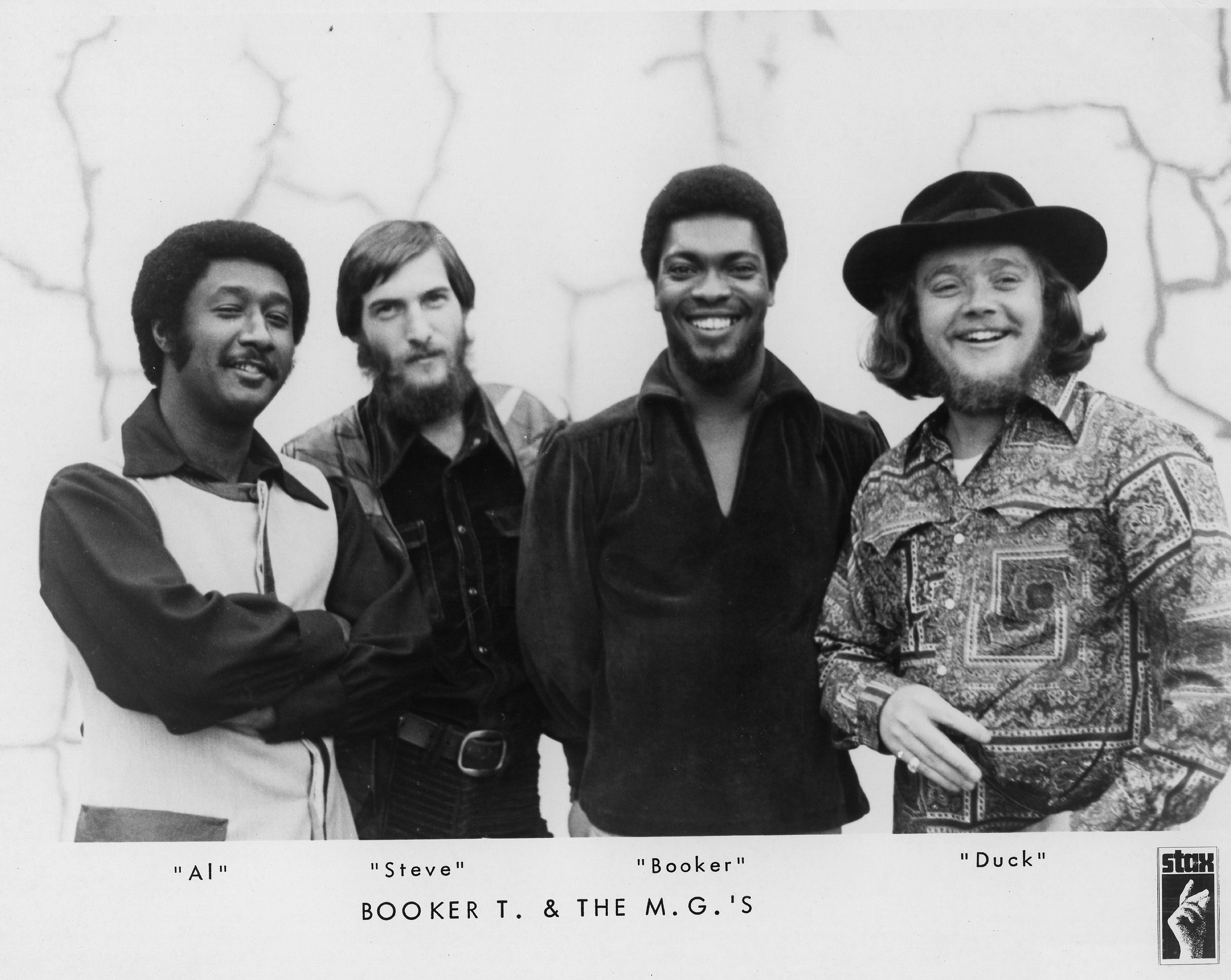

When Albert King turned up for his first session at Stax on March 3, 1966, he was met by the label’s house band, Booker T. & The M.G.’s: organist Booker T. Jones, guitarist Steve Cropper, bassist Donald ‘Duck’ Dunn and drummer Al Jackson, Jr. The latter would produce Albert’s sessions. Also present was pianist Isaac Hayes and The Memphis Horns: tenor saxophonist Andrew Love and trumpeter Wayne Jackson, supplemented by baritone saxophonist Joe Arnold. According to Cropper, he had never heard of Albert King before he began working with him but the rapport between the bluesman and the other musicians in the room was immediately obvious.

“It was amazing,” he tells The Blues. “I guess Al and Booker being black didn’t hurt any. If the whole band had been white, I don’t know what Albert’s attitude would have been. But there he is with Al Jackson and Booker, Duck and myself and he was just very comfortable. We brought the horns in, and they were a mixed group too, and he realised real quick that these guys were all getting along. We were different from what was going on outside.”

The Stax house musicians were a well-oiled machine by the mid-60s and as such, sessions seemed ridiculously relaxed.

“The guys showed up 15 minutes before recording time,” recalls Steve. “It was up to whoever the designated producer was that day to come up with the songs – or have his writers be there to show the band the songs. We all just gathered around the piano and worked on these songs until we knew the changes and the direction the song was going in. Everybody would look at each other, we worked as a team, and when everybody agreed, ‘Hey, yeah, that’s pretty good. That’s the way we wanna take this.’

“We didn’t use any music. Very few times did we jot down chord changes, or what we called ‘making out a road map’. As a rule of thumb we learned it by head – what we called ‘head arrangements’ – and that’s when we said, ‘Okay Jim [Stewart, the ‘ST’ of Stax and the label’s producer], we’re ready to roll the tape.’ And we’d all go to our positions where our mics were and start playing. I would count it off and we’d go.”

Those first sessions went well but no one thought Albert would be cutting an album at Stax; something that wasn’t usual at that time, according to Steve Cropper.“During the early 60s, an artist went in to cut a single,” he says. “You never went in to cut an album. That was not even thought about. Now, when they got enough hits, if they could follow-up and all that, then you’d say okay, maybe it’s time for an album. Then that album would be their hits, a couple of new things, then a bunch of cover songs to fill the album out. There was usually 10 tracks, or 12 tracks or whatever.

“Only in the late 60s and early 70s did we go in with the purpose of cutting an album and some single songs. And when you say single songs, you’re talking about something that would be played on the radio; that would be accepted as an airplay record.”

Estelle Axton’s suggestion that he record Laundromat Blues opened Albert’s account at Stax but it soon became apparent there was a need for more good quality material if he was really going to make his mark at the label. They cut a version of Tommy McClennan’s 1941 side Crosscut Saw which Albert had been playing for a while. “That’s one of my favourites,” says Cropper. “I love the drumbeat that Al Jackson put on that. Who would have thought of doing a calypso drumbeat against the blues? But it’s the same old lyrics: ‘Baby I’m a crosscut saw, won’t you drag me across your log.’”

It was Stax artist William Bell, famous for his ’61’ hit You Don’t Miss Your Water and his ’68 duet with Judy Clay, Private Number, who instigated the writing of the biggest song of Albert’s career, Born Under A Bad Sign. A classic was tingling in the air the moment he knocked on Booker T.’s door.

“William Bell came over to my house,” Booker T. told radio DJ Joel Selvin in 2006. “I will never ever forget this day. I had like a little rumpus room built on the back of my house with a little piano back in there. I had to close the door ’cos my wife didn’t want to hear the noise [laughs].

“William walked in and said, ‘We need to write a song by tomorrow for Albert King because he has a recording session coming up… and they need songs.’

“I just started thinking and thinking… and thinking,” continued Jones. “I remember coming up with the riff then William put his thinking cap on and the next thing I know he sang, ‘Born under a bad sign…’

‘Oh my God!’

‘Been down since I began to crawl…’

‘That’s it, man! That’s it!’

“We just sat there and wrote that song,” he continued. “We were really happy with it. We got to bed about one-thirty or two.”

For Booker, co-writing the song in the first place was more than enough magic for him but he hadn’t counted on just how spine-tingling the recording session would turn out to be.

“I got to the studio the next day and started teaching the song to Steve, Al Jackson and Duck Dunn,” he recalled. “I was playing the piano. We started playing the song, Steve and Duck played the intro and then Albert played that lick.”

Booker T. received the same jolt up his backbone that anyone that’s heard the record since has felt. “Oh man, it was like lightning hit! He just lit it up. Eric Clapton is still trying to play like that!”

If Born Under A Bad Sign seemed like a gift from the song gods then their well of generosity hadn’t quite run dry for Albert King and the cats at Stax. Steve Cropper takes up the story of the writing and recording of The Hunter, a song that seemed to just fall into their laps…

“There was a guy named Carl Wells who used to hang around the studio,” he remembers. “At the time he was an older guy, probably in his late 50s. I was the A&R director and he used to bring me lyrics that he’d written. I didn’t put much faith in him but I liked the guy; he was very sincere and very honest and hardworking. This one day he brought the lyrics in for this song called The Hunter and I said, ‘You know, this is pretty cool. Let’s see what we can come up with.’ We were looking for material anyway. So, the guys started a groove, I gave Albert the lyrics and he started singing it.”

It was that easy – and everyone in the room got a piece of the song. Booker, Al Jackson Jr, Duck Dunn, Steve Cropper and the aforementioned, persistent Mr Wells. Albert, who hadn’t actually contributed to the song’s creation, was absent from its credits. Steve Cropper explains.

“The way we used to do things at Stax was, if you were there when it was written and you contributed to it, your name went on there as a writer,” he says. “We were very honest about that. A lot of guys didn’t like it: ‘That was my idea – how come there’s three other names on there?’ Because they contributed to your song. You didn’t have the whole song. You just had an idea. You don’t get 100 per cent credit for an idea.”

Despite the brevity of the song’s creation, and its recording on June 6, 1967, The Hunter soon gathered momentum as a cover version. It took the team at Stax by surprise when Ike & Tina Turner cut a cover of The Hunter for their ’69 album of the same name; but then every song recorded at the studio was given respect as a potential hit.

“Yeah, we treated songs all the same,” reveals Cropper. “The listener, they treat the hits with more respect than they do the album cuts. In the studio we treated every song as though it was gonna be the next No.1 record. That was just our attitude. Of course, it wasn’t always the case that a song would break through, and we knew that, but that was our attitude. We didn’t give more attention to one song than we did another.”

Albert’s version wasn’t released as a single until 1969, two years after the debut of the Born Under A Bag Sign album, after Ike & Tina and a certain British rock band had their wicked way with the song. “Led Zeppelin picked up on Tina’s version, or maybe Albert’s version, and did it,” says Steve. “It’s been a pretty famous song.”

Led Zep excerpted The Hunter on How Many More Times on their 1969 debut album, Led Zeppelin. But it’s the version cut by Free on their Tons Of Sobs album (1969) that is the definitive Brit rock version. Other noble attempts include Koko Taylor’s stirring cover on her 1985 Queen of the Blues album.

Tracks like Born Under A Bad Sign, Crosscut Saw and The Hunter grooved in a way that other blues records just didn’t. And there’s a simple explanation for that…

“When we were cutting the songs with Albert, we weren’t thinking blues at all,” says Cropper. “We were thinking about dance music.”

In that regard, Steve and his cohorts had form. They’d all learned their craft in clubs and college campuses, keeping the kids on their feet for as long as possible; even when they’d exhausted their set-list. Steve explains…

“On the backside of [September ’62 Booker T. & The M.G.’s hit and mod anthem] Green Onions, which is a little song called Behave Yourself, we were just jamming around with some changes in the key of F; the kind of slow blues thing we would do if we were playing a gig with a bunch of people out there dancing and we wanted to extend the set a little bit. We’d play something they could all dance to. We would just make stuff up.” The same approach was used during Albert’s sessions.

“There’s nothing secret about this,” says Cropper, “but one of the building blocks of the game plan of the production crew at Stax was that we’d take these artists that had been singing this downtrodden sort of blues that didn’t sell, and didn’t get played much on the radio, and put more of a beat to it, make it good listenin’ happy music and have hits with it. I’ve heard B.B. King talk about that. He said the blues doesn’t have to be always sad. Blues can be ‘up’ and that’s been my theory from day one.

“Albert King was a very good example of that. Crosscut Saw… Laundromat Blues… Born Under A Bad Sign; that was very commercial music that was playable on rhythm and blues stations. So, I would say that was what contributed a lot to his success.”

One of the greatest strengths of the house band at Stax was the way they allowed an artist to be themselves. Cropper credits that approach for the success of the sessions with King. Albert just had to play the blues the way he’d always done.

“He really didn’t have to change anything,” says Cropper. “We just embellished stuff and worked around what he already had. Maybe his time for difficulty was when he had to learn a brand new song that nobody had heard before. It was probably a little more difficult for him because he not only had to learn the melody, he had to learn the lyrics, then figure out what he was gonna play. He had some difficult times and there were moments of frustration but we’d all just pat him on the back and say, ‘Man, you can do it.’”

Born Under A Bad Sign – the song, that is – perfectly nailed the feeling of blacks living and working in a south that didn’t appreciate their hard work or their powerful contribution to the region’s rich culture, and made no secret of a deep-rooted hatred based purely on skin colour. “There’s just nothing like it,” said Booker T. of the recording. “It’s African-American music. Blues. And the song said the right thing at the right time.”

It did. Race relations in Memphis – and the rest of the Deep South for that matter – were poor in the mid-60s. It’s still tense in much of the south today. Segregation was openly practised and to drink from a ‘Whites Only’ fountain – or dare to sit in a segregated cafe or restaurant – was like signing your own death warrant for any African-American with the heart to try.

The Civil Rights Movement had been gathering pace since Rosa Parks declined to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, on December 1, 1955. Tensions in the south would escalate with the instigation of the Memphis Sanitation Strike on February 11, 1968. After years of discrimination and dangerous working conditions (two employees, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, died in work-related incidents) 1,300 sanitation workers walked out. African-American Civil Rights Movement leader Martin Luther King, Jr. got involved. There was a march in support of the strikers. The Memphis police force took their opportunity to punish the marchers with tear gas and batons – a 16-year old boy was killed in the melee.

According to Steve Cropper, any tension between races that poisoned the air in Memphis at that time had never been an issue inside the studio.

“When you walked through the doors at Stax, everything out on the street stayed out on the street,” he says firmly. “You didn’t bring that inside. No one brought home or the street inside that studio. It didn’t happen. So there was absolutely zero colour at Stax Records. We were just musicians trying to make a hit record and trying to make a better life for ourselves.”

The gunshot that rang out at a minute past six on the evening of April 4, 1968 even punctured the idyllic working environment of Stax. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis (now the Civil Rights Museum) – the same establishment where Cropper hung out and wrote songs countless times with Otis Redding and other Stax artists. Even he admits that the atmosphere at 926 East McLemore Avenue was never the same after that.

Just a few months before, the mood at Stax had been one of triumph. With the August ’67 release of the Born Under A Bad Sign album, Albert finally received his coronation as one of the three Kings of the blues, alongside B.B. and Freddie. He also started to see some return for his hard work. Put simply, he finally got paid.

“We were all kind of laughing when it came to royalty time,” remembers Steve. “We said, ‘Albert’s gonna die… because he ain’t seen a cheque this big in his life!’”

The record turned the heads of a legion of young guitarists. It might just be a coincidence that Jimi Hendrix began messing around with a Flying V in the late 60s. But there’s no denying the similarities of Albert’s solo on Oh, Pretty Woman and Eric Clapton’s instrumental break on Strange Brew, the first single lifted from Cream’s ’67 album, Disraeli Gears. Clapton has never denied the influence, of course – quite the complete opposite, in fact – and it’s a flattering tribute to the impact that Albert’s guitar playing was already having so soon after the album’s birth.

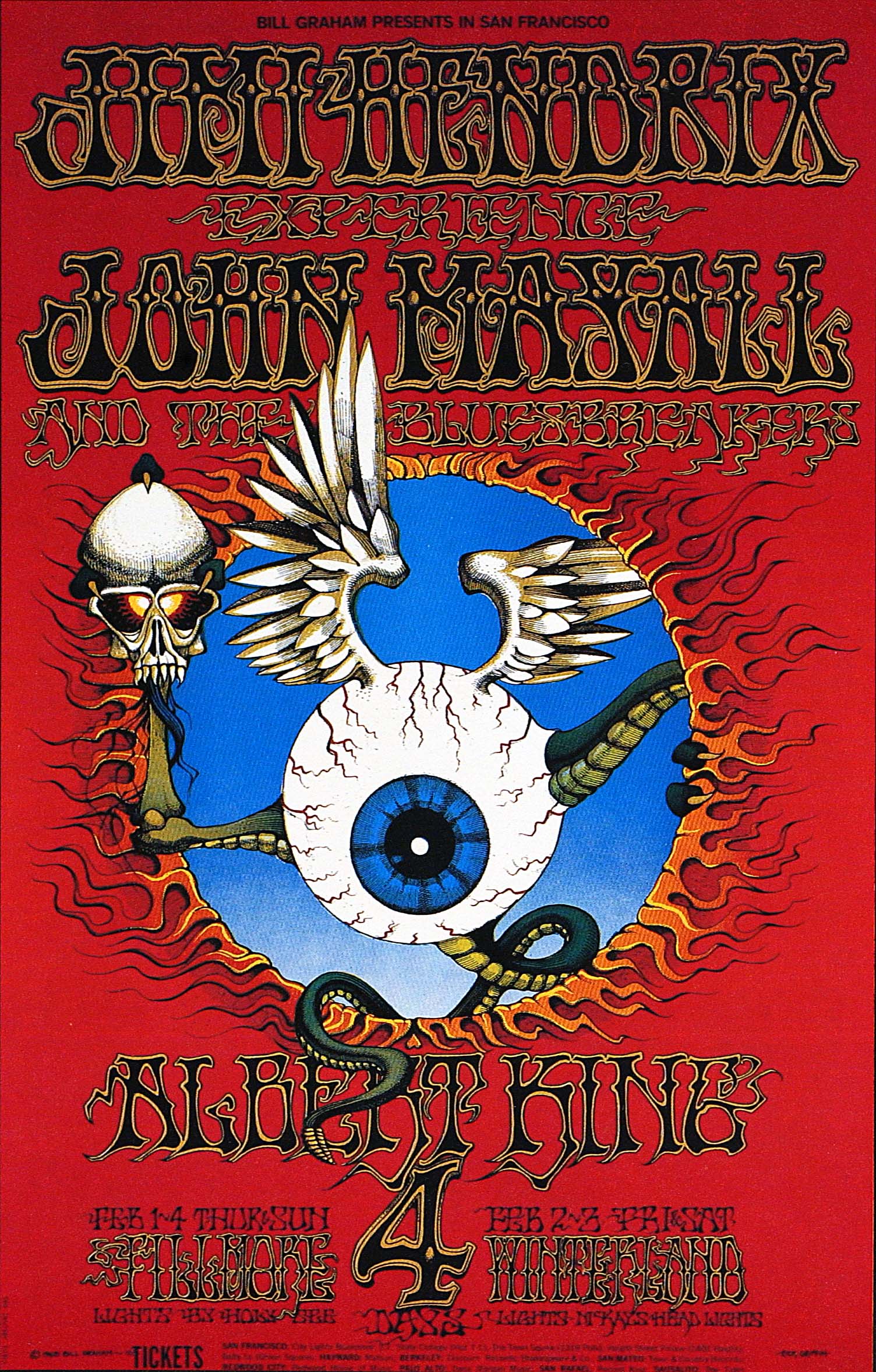

The big man’s stock was high. Like B.B. King, he suddenly found himself playing for white rock audiences, playing blues the way he always had, only this time framed by psychedelic backdrops. Cream and Hendrix both took a stab at Born Under A Bad Sign and now Albert was being offered $1,600 by music promoter Bill Graham to play three nights at San Francisco’s Fillmore. He was to play share the billing with Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix.

He left Stax in 1974, just as the label was disintegrating after years of mismanagement. The genial spirit that had made the cutting of Born Under A Bad Sign tracks so enjoyable had long since evaporated. He did manage to follow Bad Sign up with the highly-regarded Live Wire/Blues Power, recorded live at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco in June ’68; the 1969 album Jammed Together, cut with Steve Cropper and Pops Staples, has some magical moments too. But it’s that first Stax outing that created the legend and Albert never forgot the debt he owed the musicians that made up the house band at 926 East McLemore Avenue.

“The guys at Stax were real good for playing with different grooves and helping me find the right one,” he commented years later. “I liked playing with them because they were good idea people, they’d twist things around into different grooves. It worked real good.”

When Albert King died as the result of a heart attack on December 21, 1992, he was rightly celebrated as just about the most influential blues guitarist that ever dared to bend the hell out of a pentatonic scale. He’d been feted and jammed with by a new generation of guitarists like Gary Moore and, easily his greatest disciple after Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan. He become known as ‘The Velvet Bulldozer’ – he’d driven a bulldozer as a job of work in his younger days, and his voice was smooth like velvet.

Not everyone recalled their dealings with the man with fondness. To some, he was an ogre with a .45-caliber pistol tucked into the waistband of his trousers. Yet Steve Cropper’s recollections of Albert King are in stark contrast to those who found the man difficult to deal with.

“He was one of the nicest guys that I was ever around,” says Cropper. “With Albert, I wouldn’t necessarily use the word ‘love’ but he totally respected Duck Dunn and myself. He liked us a lot. When he would see us on the road it was like a reunion. We’d get the big hug… and the big handshake. ‘Hey guys, good to see you. When are gonna make another record?’”

That new record never happened, but for Booker T. Jones, he and the other guys at Stax had already cut the dream 45 and album with Albert King. There was never any need for a follow-up. “If it wasn’t for bad luck, I wouldn’t have no luck at all,” said Booker T. “That’s the blues! And we defined it a little bit that day.”

This article originally appeared in The Blues magazine #6.