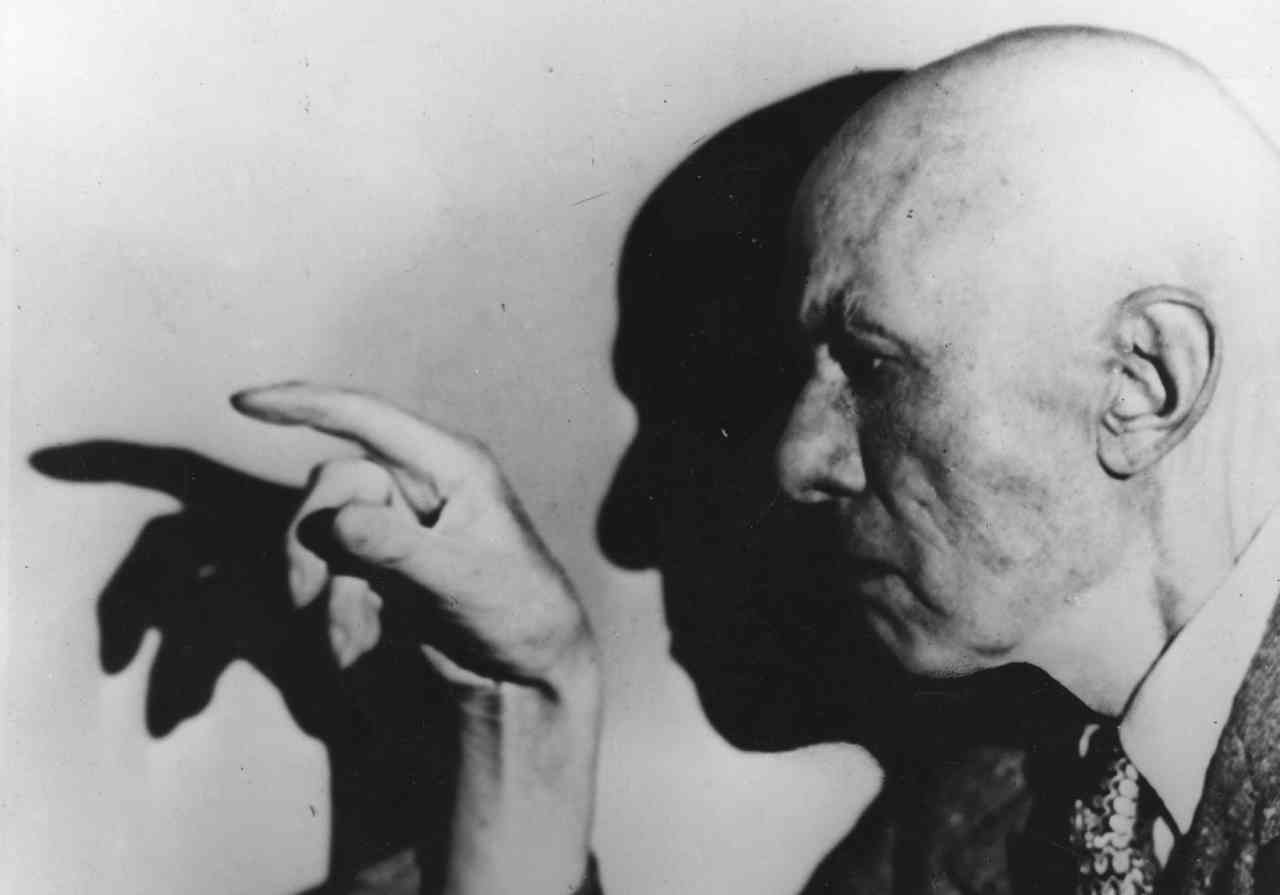

“He was called ‘the Wickedest Man In The World’ by the press – how can you fail to be fascinated by such a character?”: The twisted life and decadent times of Aleister Crowley, metal’s favourite occultist

How Aleister Crowley, aka The Great Beast, influenced generations of metal bands

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Few figures continue to cast such a huge shadow over the metal scene as Aleister Crowley, the famous – and infamous – 20th century occultist. In 2006, Crowley aficionados Dani Filth, Ville Valo and more looked at metal’s undying love affair with the man known as The Great Beast.

If Satan decreed a patron saint for rock music, it should surely be Edward Alexander Crowley – better known as Aleister Crowley, To Mega Therion, or The Great Beast 666.

“His being an outsider and his challenging of societal norms is definitely why heavy metal found an affinity with Crowley” former HIM frontman Ville Valo says. “He was one of the first rock’n’rollers. Newspaper headlines in the early 1900s said that he was the wickedest man on earth, partly because he was living outside of society’s rules.”

Part of that rule-breaking of course, came in The Great Beast’s rejection of Christianity in favour of his own more devilish creed, which sanctified sex and drugs – in which light it’s easy to see how rock’n’roll slid so snugly into the equation after his death in 1947.

“Crowley was dubbed ‘the Wickedest Man in the World’ by the press – how can you fail to be fascinated by such a character?” asks Cradle Of Filth frontman Dani Filth, who’s made frequent references to the Edwardian English occultist since Cradle closed their demo Total Fucking Darkness with Fraternally Yours, 666 in 1993. “He’s this huge figure that just leaps out from the past. If you’ve got any interest in Black Magic, or even just a passing curiosity in the occult, then you’re going to come across him at some point or another. Thumb through any reference book on the subject and there he’ll be in great big capital letters, and my father and friends had several such ‘unhealthy’ volumes which I inevitably gravitated towards when I was a kid… almost as if by magic!”

The influence of Aleister Crowley on metal spirals back to its roots in the late 60s. Spiritual experimentalism combined with the increasing availability of drugs and fad for free love to create a new congregation for The Great Beast, rescuing him from becoming a mere villainous footnote in history. The International Times – leading London hippy paper of the day – declared the Great Beast ‘the unsung hero of the hippies’.

"By the mid 60s occultism had become the latest fad, providing the rich, young and decadent with a new set of thrills" according to Gary Lachman’s history, Turn off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties And The Dark Side Of The Age Of Aquarius.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

"There were a lot of crazy West Coast Magus types around," recalled singer Marianne Faithfull of the Californian scene. "All this occult stuff had been percolating over there for ages. It existed in England too, but it was all very hermetic, gothic and secret, hidden in Crowley and much more dark and dire."

Faithfull was best known as the girlfriend of Mick Jagger, lead singer of the Rolling Stones. Difficult as it may be to believe today, in the 60s the Stones were considered a truly dangerous band – the fierce electricity of singles like Jumping Jack Flash and the exquisite darkness of Paint It Black are pure embryonic metal. The Rolling Stones flirted with fashionable occultism via Kenneth Anger. In addition to being a respected experimental film director and notorious Hollywood gossip-hound, Anger was a founder member of the Church Of Satan, and enthusiastic Crowley devotee. The fruit of this brief association was the Satanic classic Sympathy For The Devil, before a series of tragedies spooked the Stones – in the early 70s Jagger disposed of all of his occult books, took to wearing a crucifix, and stopped returning Anger’s calls.

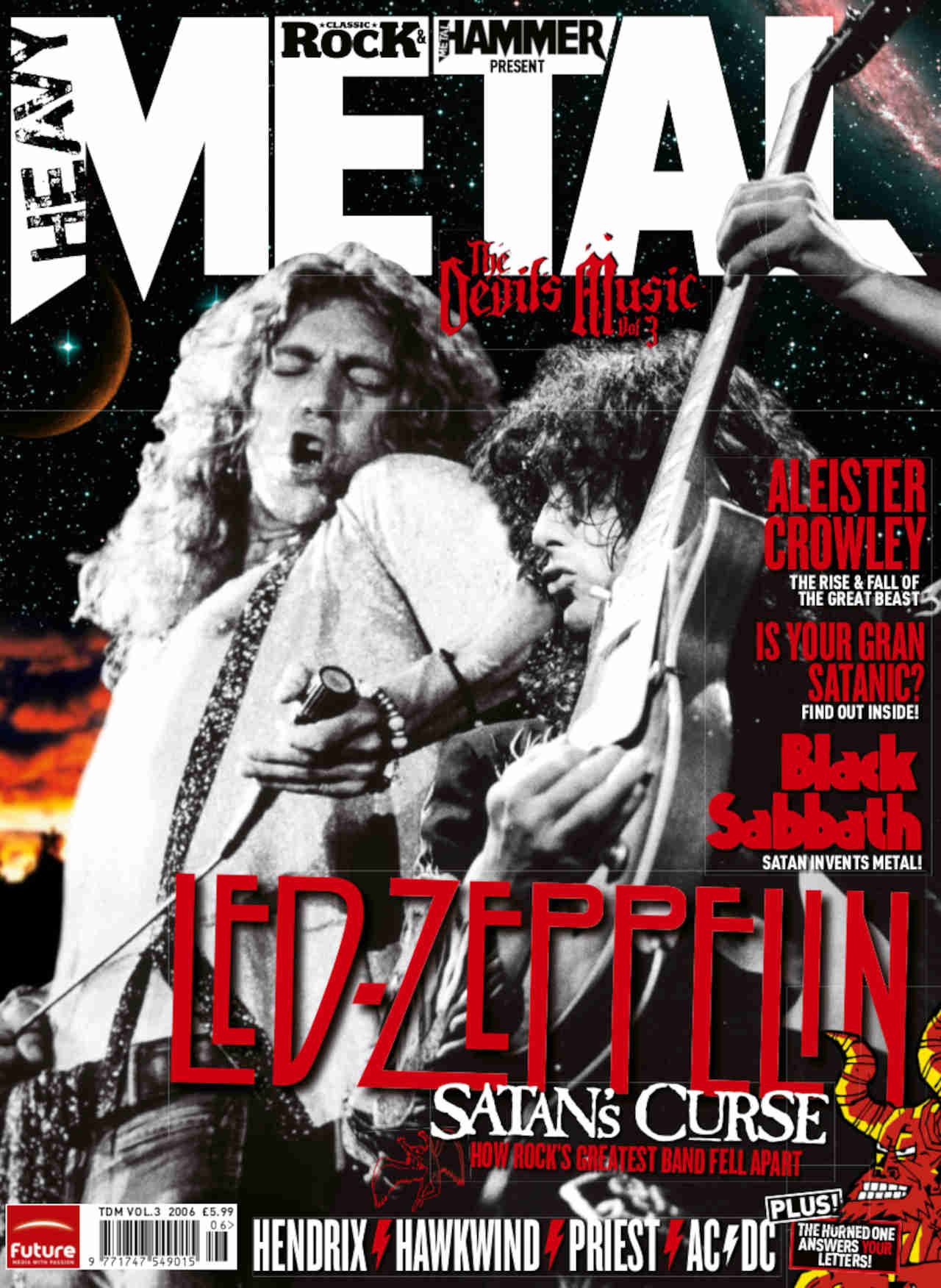

Anger’s next rock disciple was Jimmy Page, whose work with Led Zeppelin makes him among the most influential guitarists in metal history. He was also fascinated by Aleister Crowley. Led Zeppelin’s career of rock excess set a legendary standard in the 70s seldom equalled, perhaps never exceeded. To the standard recipe of drugs and groupies, they reportedly added such exotic ingredients as Great Danes, bondage, bacon, and octopi. Page is usually depicted as comparatively reserved and thoughtful in such scenes of epic sleaze, a spectator more than a choreographer of the kinky circus that surrounded Zeppelin in their glory days.

Maybe the diffident guitarist felt the occult rumours helped keep his bad boy image on a par with those of the more conventionally depraved members of the band. More likely, Crowley’s voluminous volumes gave welcome food for thought during the endless touring, when perhaps even the orgies threatened to become boring.

The Great Beast’s philosophy, itself the product of heroic quantities of sex and drugs, seems to speak to those reflective rock gods for whom too much is not enough. Crowley’s creed suggested that perhaps mindless copulation and consumption of narcotics might actually mean something.

A girl who claims to have previously been intimate with Page, referred to only as ‘Pamela’ in the notorious Zep biog Hammer Of The Gods, insists the guitarist was “really into black magic, and I think probably did a lot of rituals, candles, bat’s blood, the whole thing. I believe he did that stuff. And, of course, the rumour that I’ve heard forever is that they all made this pact with the Devil, Satan, the Black Powers, whatever, so that Zeppelin would be a huge success.” When things started going wrong for the band, some pointed the finger at Page’s occult interests, and the legend of a Led Zeppelin curse was launched to account for the building ill-fortune that ended with the band’s collapse in 1980.

Jimmy Page has since downplayed his past firtations with the doctrines of The Great Beast – at the time the guitarist kept such interests to himself, even from fellow band members. The closest Page came to candour about his belief in the occult (which, after all, literally means ‘hidden’) was in a 1975 interview for Crawdaddy! magazine, though he listens more than talks. The reason was probably the elderly celebrity interviewer – high priest of heroin chic and beatnik legend William Burroughs. While the beatniks were principally into jazz, Burroughs was impressed by Led Zeppelin live.

"A rock concert is in fact a rite involving the evocation and transmutation of energy. Rock stars may be compared to priests," he said.

He continued: "Jimmy expressed himself as well aware of the power in mass concentration, aware of the dangers involved, and of the skill and balance needed to avoid them… rather like driving a load of nitroglycerine. 'There is a responsibility to the audience,' he said. 'We don’t want anything bad to happen to these kids – we don’t want to release anything we can’t handle.' We talked about magic and Aleister Crowley. Jimmy said that Crowley has been maligned as a black magician, whereas magic is neither white nor black, good nor bad – it is simply alive with what it is: the real thing, what people really feel and want and are. I pointed out that this 'either/or' straitjacket had been imposed by Christianity when all magic became black magic; that scientists took over from the Church, and Western man has been stifled in a non-magical universe known as 'the way things are'. Rock music can be seen as one attempt to break out of this dead soulless universe and reassert the universe of magic."

While Page turned his back on the teachings of The Beast in the 80s, other metal musicians were beginning to take an interest, though not to universal approval. In 1988 the journalist, poet and Crowley enthusiast Sandy Robertson published his Aleister Crowley Scrapbook, which he concludes with a chapter on ‘The Crowley Industry: Rock And Beyond’.

Robertson acknowledges Jagger’s contribution, that of pop chameleon David Bowie, and of Jimmy Page – though only after insisting that Led Zeppelin are ‘(not a heavy-metal band – listen)’. As for the rest of metal’s contribution to the Crowley canon: "If the best is Ozzy Osbourne yowling about ‘Mr Crowley’, you can imagine what the worst sounds like, " he sneers. "For the most part these groups have no real knowledge of Crowley’s ideas and are only interested in sensationalism and selling vinyl."

Robertson prefers the more obscure end of the musical spectrum – cult artists like the comical Current 93, or the more interesting, but equally impenetrable Coil. He forgets that the Crowley was himself a rabid publicity hound, interested in mass notoriety more than cult credibility. Given the opportunity, The Great Beast would have fronted Black Sabbath, not courted the bed-sit intellectuals. There’s a tendency among Crowley’s current disciples to dismiss anything they regard as ‘theatrical’ – condemning any such showmanship as ‘sensationalism’. Yet Crowley himself was the quintessential showman, an exhibitionist who travelled in character as Indian guru Mahatma Guru Sri Paramahansa Shivanji, the Scottish Laird of Boleskine, the Persian Prince Chioa Khan, among others, all to create a sensation.

“Self-publicity is part of being a magician,” says Dani Filth. “You don’t have to stand on some storm-swept mountain – raising your hands, intoning some spell and opening some gateway to some unearthly dimension. Well I suppose you could but that’s all a little H.P. Lovecraft… In a sense, Crowley did on several occasions, but not in the clichéd Hollywood sense, where the sky fills with demonic faces and whole towns are levelled. Of course Crowley was a self-publicist. You have to make a name for yourself. That’s part of how Magic works – by influencing the minds of others. If nobody knows who the hell you are, you’re not much of a magician really.

“I’ve always felt some kind of empathy for Crowley – hence one of the reasons for wanting to cover Ozzy Osbourne’s classic song Mr. Crowley,” Dani continues. “I have always thought of him being like the definitive ‘Byronic Man’ – misjudged, pilloried and misquoted in the press of the day and to the commoner, something of a likeable public scoundrel. His maxim ‘Do what thou wilt’ still rings true when we are together as a band. These are the moments when we feel that, in the words of the author H.P. Lovecraft, ‘the stars are right’ and things fall into place in accordance with a combined will.”

Looking at Ozzy Osbourne today, it’s difficult to take him seriously as anything, let alone a serious commentator on the philosophy of Aleister Crowley. At the time he wrote the song, Ozzy was a heavy substance abuser, sinking into a pit of excess, berated by the press and public as a depraved devil-worshipper. Not unlike The Great Beast himself you might say. Crowley was a great believer in material channelled through him, that the author or composer can be a mere medium for what they create.

More than one Crowley expert of this writer’s acquaintance has felt obliged to confess that, however it happened, Ozzy Osbourne’s lyrics capture the spirit of the Beast better than the likes of Led Zeppelin. “Mr Crowley, won't you ride my white horse?”, for example is a symbolic reference to sex or drugs that’s 24-carat Crowley. The song’s opening line – “Did you talk to the dead?” – is inaccurate. Necromancy is one of the few black arts Crowley didn’t undertake. But the rest of the song addresses the ambivalence of his philosophy, and epic essence of The Great Beast’s bizarre life, with striking power. In particular, Osbourne’s closing refrain – “I want to know what you meant” – is appropriate.

The Beast himself confessed that he never truly understood his own masterpiece, The Book Of The Law, dictated he said by his Holy Guardian Angel, Aiwass, possibly the Devil himself. Should it ever be properly interpreted, said Crowley, it would lead to cataclysm, and some attribute the calamities that stalked its author to his compulsive attempts to do just that.

“He was very religious, but religious in his own way” Ville Valo says of The Great Beast. “He was trying to find this ‘other’ place, a spiritual balance through painting and writing. He said that when you’re fighting for a spiritual balance you are no longer thinking about good or evil, that life, like people, is not black and white. Good people are able to do bad things and bad people are able to do good things. All the ritualistic aspects of Crowley are really far out. I’m not a great believer, but that doesn’t mean I can’t read his work.”

“Was he a madman or a genius?” ponders Dani Filth. “I sort of lean towards genius. I’ve read a lot of his works, and certainly sometimes he was a complete genius. I think he went off his head at some point, but I still think he was one of the sharpest English occultists that ever lived. People were genuinely scared of him, and he had a laugh at their expense. He had a laugh at a lot of other people’s expense.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer Presents: The Devil’s Music Vol.3, Secptember 2006