As the 1960s dawned, Phoenix was a bland, monochrome city in the middle of the Arizona desert. Tumbleweed blew through the streets and, while the sound of the Beach Boys dominated the syrupy airwaves, nobody was about to go surfing.

Phoenix was home to Alice Cooper – born Vincent Damon Furnier, a preacher’s son who moved to the city from Detroit with his family, when he was 13. Young Vincent had been afflicted with asthma from birth, and the city’s arid conditions were expected to improve his general health. But within two months he’d developed peritonitis from a burst appendix.

“I was only 98 pounds and had spent a year and a half hunched over in bed, which left a curvature of my spine and shoulders which could have put the Hunchback of Notre Dame to shame,” he later recalled of an adolescence that was not so much carefree as a gothic Edgar Allan Poe tale of musty, shuttered sickrooms. It was enough to make a boy morbid.

Battling back to health thanks to an enthusiasm for long-distance running, Vince first made the acquaintance of Dennis Dunaway on the Cortez High School Track & Field and Cross Country team, though the pair bonded during art class.

Shortly before putting the finishing touch to his distinctive profile by collapsing face-first onto his nose after taking the Phoenix marathon record, Vince – along with the rest of civilisation – discovered The Beatles. Suitably enthused, he and his fellow Cortez Track Team Lettermen formed their first ‘band’, The Earwigs, playing their inaugural gig at a spring 1964 talent show.

“Glen Buxton played guitar and another Cortez Letterman guy, Phil Wheeler, played a snare drum,” says Dunaway. “John Speer and I sang and pretended to play guitars, while Vince sang and pretended to play ukulele. We changed the lyrics to Beatles songs to be sports oriented. We wore cheap Beatles wigs and had a blast.”

So why was Vince Furnier chosen to be the singer? What set this shy and sickly preacher’s son apart from the rest of The Earwigs?

“Vince was always losing things – he left a trail behind him – so we knew he’d never be able to keep track of an instrument,” says Dunaway. “He had a knack for remembering lyrics, which none of the rest of us had. And even though he was just a skinny nerd with a wimpy voice, if you looked closer, he was exceptionally congenial.”

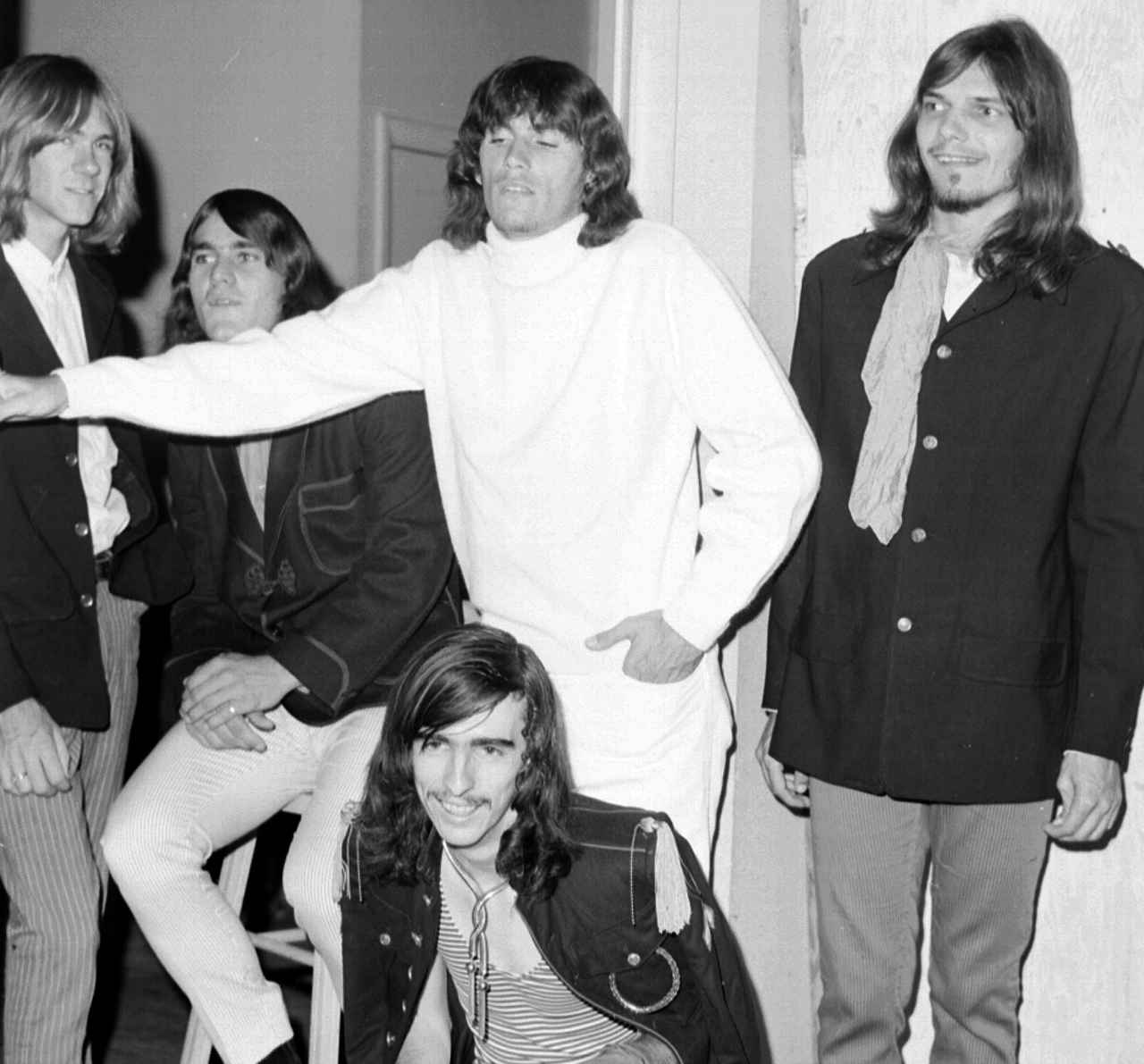

From humble beginnings, The Earwigs gradually became a tight unit, entering talent shows and Battle Of The Bands competitions. As they became more accomplished, they changed their name to The Spiders, recording their Who and Yardbirds-influenced debut single, Why Don’t You Love Me?, in 1965. With each stylistic shift and discovery of a new Brit Invasion template, came another name-change. If The Earwigs were The Beatles, The Spiders were The Rolling Stones: grungier, less formal. The Spiders’ follow-up single, 1966’s Don’t Blow Your Mind, garnered them a strong following around Phoenix. By the time the band started to venture to Los Angeles for shows, they were calling themselves The Nazz. Shortly after moving to Santa Monica in 1967, The Nazz settled on a five-man line-up of Furnier, Dunaway, lead guitarist Glen Buxton, rhythm guitarist Michael Bruce and their latest recruit, drummer Neal Smith.

“Michael was a high school football player with a brutish attitude,” remembers Dennis Dunaway. “But he had an equipment truck and could sing harmonies, so he was in. Glen was a true rebel. He stayed up late, slept late, got away with anything he could. He despised rules of any kind and anyone who tried to enforce them. That attitude permeated his guitar playing as well as the band’s image.

“Neal had a dynamic, flamboyant stage presence and was masterful at exploring abstract musical places. He kept everyone laughing, and he’s a lady-charmer too,” continues Dunaway. “I was the artistic dreamer – excruciatingly quiet. I rarely spoke a word unless it was about music or art, but when it came to those things, I was a die-hard crusader for creating things that had never been done before.”

“Dennis had a lot to do with the insanity of the band,” says Alice today. “He and I were both artists in school, and from the Dalí surrealistic movement.”

By March 1968, both Vincent Furnier and the band were answering to the name of Alice Cooper. But who and what was Alice Cooper?

“I was creating a fantasy,” says Alice today. “I looked all around me and saw all these Peter Pans with no Captain Hook. I saw the Black Queen in Barbarella and said ‘That’s Alice, right there’. I immediately related and knew a piece of Alice had to look like that; the black gloves with the switchblades coming out of the end, the black make-up with the patch over her eye. Then I would see something else in a comic book and go ‘Oh, that’s definitely Alice’. So I started stitching all these characters together and pretty soon, there he was. All I had to do was put his skin on and feel comfortable in there.”

So that’s the ‘who’ and the ‘what’. But what about the ‘why’?

“In the early days, Vince was shy,” says Dunaway. “He’d stand with his back to the audience the whole set. So at rehearsal, when we were still starving in California, I suggested he develop a different character for each song. When we played covers he had no problem being Keith Relf or Mick Jagger, but when we did our own material he was at a loss as to who he was and what he wanted to project. So when we did Nobody Likes Me, he became a lonely guy singing through a window; on Levity Ball, Gloria Swanson at the end of Sunset Boulevard. In the middle of Fields Of Regret there was a dirge that sounded like a sermon, influenced by Alice’s father being a minister, and Alice became this darker, more sinister character,” says Dunaway. “The audience loved that song, so one day I said, ‘We should write more songs for that character’. It didn’t happen overnight, but by the time we recorded Love It To Death the concept of Alice becoming that sinister character on more songs had really taken root.”

In the southwest, guys with long hair were easy targets for cowboys in pick-ups and cruisers in hot rods. But the move to the full-scale Hollyweirdness of psychedelicised Los Angeles nurtured Alice Cooper’s spirit of reinvention.

“Our first walk down Sunset Boulevard was an eye-opener,” says Dennis Dunaway. “I’d never even heard the word ‘silicone’ before, and there it was in all of its see-through-blouse glory. Names like The Byrds, The Doors, Love, and Jimi Hendrix Experience were on the marquees of Gazzari’s and the Whisky A Go Go – and everywhere you looked there was a yellow convertible with two blondes in sunglasses. And a heavy LAPD presence: a hint of trouble in the air; I thought it might have been mace. It was all so foreign and intimidating, but we knew we had to start over as small fish in this thoroughly enticing big pond.”

Despite the band’s reluctance to fully embrace every aspect of the free love generation (“I couldn’t see pot as a social high, so I’d pretend to take a hit,” says Dunaway), they quickly bonded with the freaks.

“The Mothers Of Invention, Jimi Hendrix, The Doors and their girlfriends were friends of ours,” says the bassist. “Those friendships offset everyone else’s ridicule of our unignorable name and image. Pam Zarubica [who sometimes performed as Suzy Creamcheese with Frank Zappa] was a good friend. We also knew Sunset fixtures like Rodney Bingenheimer, Kim Fowley and Wildman Fischer,and all of those darling, naughty groupies. We loved The GTOs for their explosion-at-the-circus look.”

It was The GTOs’s Miss Christine who fixed the band up with their pivotal audition with Frank Zappa, after much cajoling and begging. The band were given a 7pm appointment, but due to crossed wires they turned up and played at 7am.

“We set up right outside Frank’s bedroom door,” says Dunaway, “and played so loud that the pictures on the wall ended up crooked. We woke him up with that. I thought he’d shoot us, but he offered us a recording contract. I liked Frank a lot. We both loved doo-wop and electronic music, so he’d invite me over and play records for hours. He had ideas about what to do with us, but I think he quickly realised that we were our own thing. He produced our first moonlight session on Pretties For You but then he called in sick.”

Alice remembers the sessions for Pretties For You, the band’s first album, recorded in 1968 for Zappa’s Straight Records (though it wasn’t released until August 1969), as a whirlwind of creativity and soundboard bafflement.

“Well, first of all we had Frank Zappa running the boards,” he says. “And here we are with these really insane little songs. Songs like B.B. On Mars and 10 Minutes Before The Worm, pieces like that. He was going, ‘What’s with these songs? What are you talking about?’ And I’d go, ‘I don’t know.’ It would be like a minute and a half song with 35 changes. And he’d say, ‘I don’t get it! I like you guys, but I don’t get it!’ And I would say: ‘Well I don’t get it either, but these are our songs’.”

“Pretties For You was an animal unto itself,” says Dunaway, “And whatever the performance or production values, I’ll always admire it as a bona fide work of art: four nights in a row, midnight till dawn. We were greener than green, and abandoned mid-stream, but we had a passionate collective vision thatonly five people in the world had. And blow-by-blow against us making it happen properly, we never doubted our mission for a second, because it was a pure one. But it didn’t put a crumb of food on the table, so we decided to write an album with songs that people could relate to.”

That album was the follow-up, Easy Action, but it failed to give them the breakthrough they wanted. While they were desperate for a budget and producer sympathetic to their artistic vision, they were too poor to afford production and were saddled with Neil Young’s long-time producer, David Briggs. Neal Smith remembers: “David hated our music and us. I recall the term that he used, referring to our music, was ‘psychedelic shit’.”

There was a more fundamental flaw, too – the band’s apparent inability to write the kind of coherent material that would furnish them with a hit record.

“We still hadn’t learned how to predetermine the direction of a song,” says Dennis. “It was like we would close our eyes and fire a shotgun at a blank music sheet, and the holes formed the notes for a surprising new song. We were working on songs in cars, motel rooms and at sound-checks in beer joints. And just as we were getting started, we got a call insisting that we get into a studio and record, some contractual obligation or something. And so, against our artistic wishes, we winged it through Easy Action. I believe that a proper place to rehearse and another month would have brought that album more toward the cohesion of Love It To Death.”

Alice agrees the band were nearing their manifest destiny, but feels that Easy Action could only ever have been a means to an end rather than an end in itself.

“After doing the first album, we did get better. We were listening to other things, and gaining confidence after Pretties For You, but those first two albums were both just leftover Nazz songs,” he says. “We’d only just changed our name when we met Frank. We were The Nazz up until then: just this little psychedelic band from Arizona. So I don’t really consider those to be Alice Cooper albums.”

Just prior to the long-delayed release of Pretties For You, the band moved to Detroit, as The MC5 and The Stooges were operating at their feral peak.

“Despite the illusion of finally conquering Hollywood with shows at the Whisky with Led Zeppelin, a long string of engagements at the Cheetah, and a slightly noticeable album with Zappa’s significant association, we left that town broke, with our tails between our legs,”says Dennis Dunaway. “We were too weird for Hollywood. So we threw all of our beer cans out the window and hit the road playing every beer joint 10 times over. And each time we hit a town, we had to check into motels with fake names because of our deserved reputation as cheque-bouncers. It was an unwelcoming vacuum out there. We couldn’t have toned down our looks if we tried, so we clomped into diners in our full shock regalia. That never went smoothly.”

The Midwest was more in tune with the band’s line in tough, ever-more theatrical freakery, so they holed up in a dive motel near Detroit and were soon adopted by the fiercely competitive, revolution-charged local scene.

“This was another landmark learning experience for us,” recalls Dunaway. “The Stooges and The MC5 were wearing jeans when we showed up, but Iggy started wearing gold lamé gloves and The MC5 donned shiny fabrics, which made a fair exchange because their incredible high energy was a very important influence on us.”

With Easy Action failing to set the world alight, Alice Cooper continued to gig, each performance infused with a modicum more Detroit rage and frustration than the last, until September 8, 1970, when they played a show at New York’s Max’s Kansas City club. It was a night that would become notorious for two things. First, according to legend, Alice was arrested for using the word “tits” on stage. Second, a young Canadian by the name of Bob Ezrin was in the audience on behalf of his boss, famous record producer Jack Richardson of Nimbus Nine. Ezrin was so impressed that he convinced his boss to sign the band, against Richardson’s wishes. Not long after, his first collaboration with the band, I’m Eighteen, was released. Dennis Dunaway remembers the sessions as fraught with nerves.

“Keep in mind that we initially thought Pretties For You and Easy Action were going to set the world on fire,” he says. “So, with two strikes against us, we were gun-shy, and even though the music sounded better than ever, we felt it was our final shot, so we were treading on thin ice during those sessions. It really didn’t hit me until Rosalie Trombley started playing I’m Eighteen on CKLW out of Windsor, Canada. Their listener requests came in such a tidal wave that they moved it into their heaviest rotation. Every fifth song was I’m Eighteen. Love you, Rosalie. Yippee!”

I’m Eighteen peaked at number 21 in the US singles chart. In June 1971, Love It To Death, Alice Cooper’s first album to benefit from Bob Ezrin’s dynamism, judicious editing, theatrical vision and commercial ear, capitalised on I’m Eighteen’s breakthrough success to infiltrate, corrupt and generally degenerate the prevailing Laurel Canyon sensitivity of the American Top 40. Alice Cooper’s time had finally come.

“We were just a garage band that had all the right stuff,” concludes Alice of the band’s difficult birth. “We had the right ideas, the right theatrics, the right sense of humour and the right drive to get this done. We were at the right place at the right time.”