Alien Weaponry: Three Māoris and an entire nation of Navajo metalheads

What happens when you follow the most exciting young metal band in the world into the heart of the Navajo Nation? We join teenage sensations Alien Weaponry on an adventure like no other

WEAPONRY! WEAPONRY! WEAPONRY!” The crowd inside Window Rock Sports Center chant and stamp the floor, as President Nez of the Navajo Nation presents their flag to Alien Weaponry. The New Zealand trio are mid-gig in the capital of the largest Native American reservation in the States, and the noise is thunderous.

Earlier today, the band enjoyed a private audience with the President. “It’s crazy to think he’s a metalhead,” marvels frontman Lewis de Jong. “It’s an honour that our music has brought us to the point where we are meeting the head of America’s biggest native tribe.”

Despite his wonderment, it’s not the first time the band have crossed paths with a political leader. They’ve twice shaken hands with Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand’s Prime Minister, and their reputation is growing rapidly at home and beyond.

They’ve made a name for themselves thanks to modern groove metal anthems sung partly in te reo Māori, the indigenous language of New Zealand. Many of the songs on 2018’s debut, T, outline the injustices perpetrated against the Māori people in the name of colonisation, and the fallout that continues today.

Following its release, they toured internationally, playing memorable sets at Wacken and Bloodstock, and supporting Ministry in the States. This year, they opened the main stage on the Saturday of Download, went viral with a giant group haka performed at Denmark’s Copenhell, and returned to the US with Black Label Society. They’re currently coming to the end of a US headline tour. All this, and they’re still in their teens.

“Some days I wake up and I’m like, ‘Is this even real life, what I’m doing?’” says 17-year-old Lewis, trying to comprehend their recent rise. “Sometimes I tell people what I do, and they just look at me and don’t believe me, especially given how young we all are.”

The reservation – which spans Arizona, Utah and New Mexico – has a special place in Alien Weaponry’s hearts, because they played their first- ever US headline show here. After getting banned from Ministry’s Salt Lake City venue last year due to their age, they reached out to Navajo promoter Randall Hoskie, who had previously invited them to the Nation, and sold out a show in nearby Gallup.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

But it’s not the only reason it has a special place in their hearts. Not only do the Navajo people embrace metal – some of the local bands even refer to themselves as ‘rez metal’ - they recognise similarities between Māori culture and their own native culture. “I guess because we sing in our indigenous language about colonisation, a lot of Navajo people relate to that,” says Lewis. “So when we play shows here, people go above and beyond to accommodate us. It’s an awesome feeling.”

When we pull up to the venue this morning, Lewis is leaning against the tourbus getting his undercut shaved by stand-in bassist Bobby Oblak (permanent bassist Ethan Trembath, 17, is sitting out this run to finish school). They greet us with sheepish laughter, and we head inside to meet Lewis’s brother, 19-year-old drummer Henry.

Alien Weaponry is a family affair; dad Niel is their sound engineer, while mum Jette quit her job as a campground receptionist to become their tour manager/merch salesperson. It’s a tight squeeze on the bus.

“I think the most challenging part is being squashed together in the same space,” grins Jette, flashing the world-weary look of not just a mother, but a mother who’s been on the road for six months. “And teenagers who are naturally trying to separate themselves from their parents, and parents who are quite happy to get rid of them, to be honest, but still feel like we wanna support them!”

It’s due to their support that Alien Weaponry have come this far. Former professional musician Niel raised his sons on Rage Against The Machine and Metallica, and they began writing their own songs while they were eight and 10 years old, taking their name from 2009 sci-fi film District 9.

Lewis met Ethan at an after-school circus club in their small hometown of Waipu, and Niel taught him how to find his way around a bass. The trio were soon regularly entering an annual youth music competition called Smokefree Rockquest.

Jette also remembers an early paid show on Auckland’s Karangahape Road, or ‘K Road’, which is “notorious for strip clubs and brothels”. It was advertised as an aftershow party for Steve Vai, but it transpired that he wasn’t involved.

“They turned up, they had only written four songs, and there were no other bands there and no proper PA. So they just played their four songs four times, and people thought they were great!” laughs Jette. “We told them they weren’t allowed to go on the street, but their eyes were popping a bit!”

For Lewis, music was escapism from school. “I was a different kid,” he explains. “It was a 500-kid school, and there were two kids that listened to metal. I had long hair, and on mufti [non-uniform] day I’d wear my black jeans with my black Lamb Of God shirt. When you’re a different kid, people don’t like that. They pick on you.”

The turning point for Alien Weaponry came when their friends’ ska/reggae band, Strangely Arousing, entered Smokefree Pacifica Beats – a sister competition to Smokefree Rockquest, for music reflecting New Zealand’s cultural identity. Strangely Arousing’s song featured a chorus in te reo Māori, which Lewis and Henry were familiar with, as their parents had sent them to full-immersion Māori pre-school and primary school.

“Usually when people write songs in M ori, it’ll be rap, reggae, R&B or traditional Māori music,” Lewis explains. “So we were just like, ‘What if we enter that competition, singing about some brutal history shit?’ And we made the song thrash metal, because why not? The first time we ever played R Ana Te Whenua live was in front of a panel of four judges [in 2015], and they absolutely loved it. We ended up winning that competition the second year we entered it.” The same year, they also won the Rockquest.

Starting with fearsome warrior chanting and dramatic drumming, R Ana Te Whenua tells the story of the brothers’ great-great-great-grandfather, Te Ahoaho. He was a war chief who fought and died in the battle of Pukehinahina in 1864. During the battle, 230 Māori warriors successfully defended themselves against a 1,700- strong British army. It was part of the Tauranga campaign, a six-month-long armed conflict about issues of land ownership.

Some of the background to this conflict is explored in another song, Raupatu. As a message in its music video explains: ‘In 1863 the New Zealand colonial government passed a law enabling the confiscation of lands from anyone they deemed to be ‘rebels’.

In this way, millions of acres were stolen from their Māori owners, plunging these communities into poverty and changing the balance of power and the history of the country forever. These unjust actions were called raupatu.’ It’s another defiant thrash attack, with lyrics proclaiming: ‘You take and take, but you cannot take from who we are.’

“Our dad is very connected to his Māori side of the family, so we were always being taught about that stuff,” explains Lewis. “In our music we bring a light to things that haven’t been talked about enough, as far as things that the government have done which are not right to Māori people.”

Lewis' Māori heritage comes from his paternal grandmother’s side, while his mother is Dutch. He feels more strongly connected to his Māori side, especially through his activities with the band, and is sad to see other young people rejecting it.

“A big problem in New Zealand is that a lot of Māori people don’t feel proud of being Māori. They don’t want to adopt their culture and they don’t want to learn the language, and then it kind of puts them in a position where they don’t have an identity,” says Lewis.

“A lot of Māori people have adopted African American culture; sometimes they call each other the ‘N’ word because they think it’s cool, but there’s a lot of fucking history behind that. What we’re trying to do is make people want to be themselves and embrace who they are.”

Dad Niel feels a kinship with the Navajo Nation. A tall, long-haired, softly spoken man, affectionately referred to by the band as ‘Hagrid’ from Harry Potter, he says that there’s a sense of familiarity when it comes to the way people here run their community.

“The most striking parallel is what we in Māori call ‘whanaungatanga’, which would translate to ‘family connection’,” he says. “A strong focus on family, particularly family ties – who your cousins are, who your second, third and fourth cousins are, who you descend from, how your grandparents are related to other people’s grandparents. All of those things are a very important part of Māori culture, and it seems also talking with our Navajo friends, a very important part of Navajo culture.”

Nevertheless, he describes colonialism as “the great, big, white elephant in the room”. Its effects have been complex and wide-reaching, and he points to the socioeconomic difficulties and the suppression of native culture alongside the more obvious physical battles. When it comes to Māori people, Niel echoes Lewis in saying there has been a loss of “mana”.

“In Māori it means your pride or feeling of self-worth, but also it’s a worth that other people would give you or afford you as an individual of high standing,” he says. “And I think a lot of our communities, particularly over the last 200 years, have had that eroded away.

Our elders were not given the respect and appreciation by outsiders. And it rubs off on the communities who then start to not value their elders or community leaders either. It’s a very subtle thing.”

Luckily, circumstances are improving as the government makes reconciliation efforts, but nothing can compensate for loss of life, and the repercussions of history are regularly visible in the headlines; there’s currently a dispute over construction work on sacred land at Ihumao near Auckland’s airport, originally seized by Britain in 1863.

Last month, a village banned a replica of British navigator Captain Cook’s ship from docking there to mark 250 years since his arrival, following an outcry from the local Māori community.

The Navajo people have endured their own myriad struggles, not least brutal forced relocation in the 1860s. But for Council Delegate Edmund E. Yazzie, the main connection with Alien Weaponry is the music, and he’s thrilled to have them here.

He grew up listening to Dio and Iron Maiden, and drums in his son’s band, Testify, who supported the trio in Gallup last year. For him, metal relates to Navajo culture because of “the drum beats, the riffs” – a twist on traditional drumming.

Recognising the potential of metal on the reservation, he lobbied the council to support it. Despite some initial raised eyebrows, Testament played annual celebration the Navajo Nation Fair in 2017, followed by Anthrax the following year. Meanwhile, there’s a thriving metal community, with around 30 bands.

“We’re noticing talent is on the rise with us Native Americans, and so we’re trying to keep the metal scene strong and alive,” enthuses Edmund. “Every year the fair introduced country bands. But because of us advocating for the metal scene – the President and everyone thought I was crazy, but they started to adapt! – we got bands coming in like Anthrax and Testament. We’re very fortunate.”

President Jonathan Nez chats about his friendship with Max Cavalera, who is playing in a few days. “The Navajo people enjoy heavy metal, and that’s why we invite other heavy metal bands from throughout the world to perform,” he explains. “It’s a time to bring families together.”

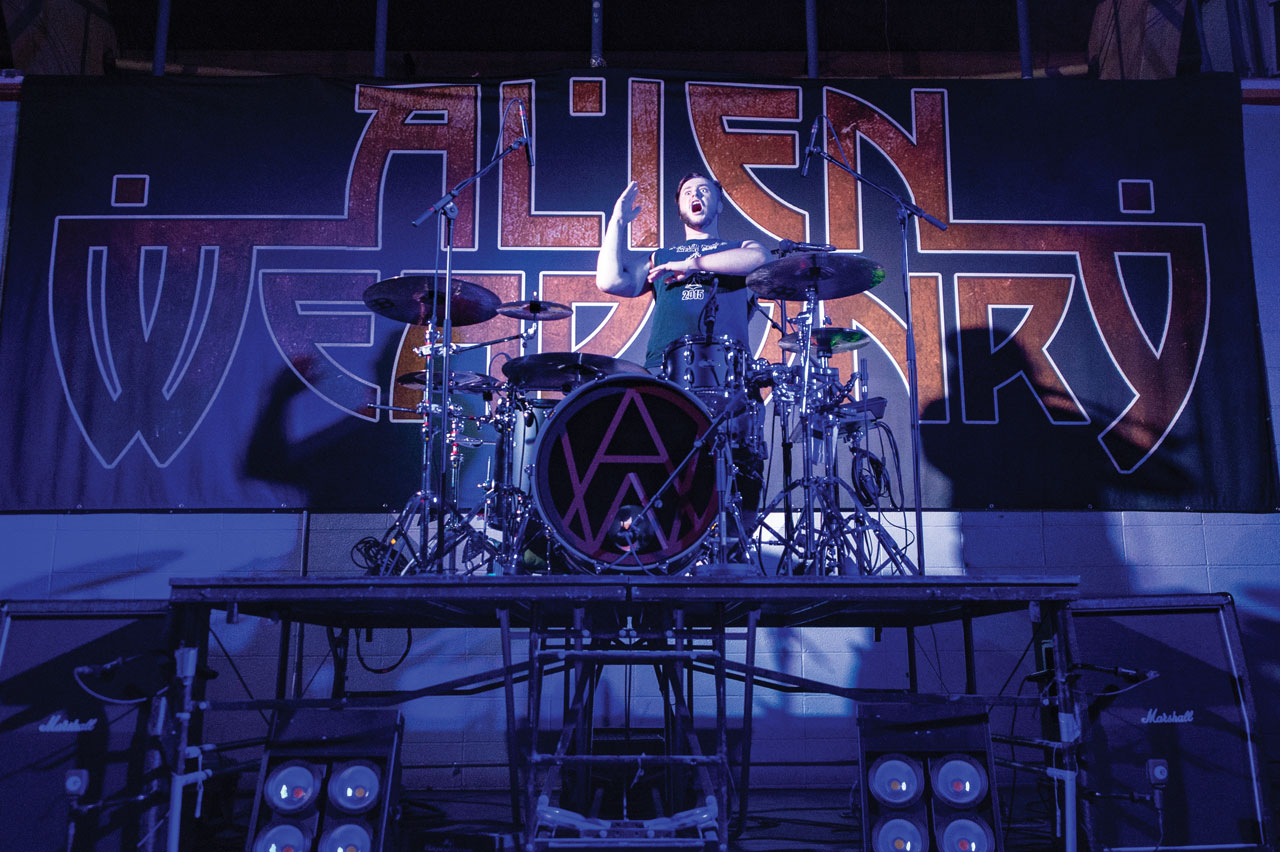

The Sports Center is buzzing tonight. Local talent Alchemy, One Bullet Away and Born Of Winter warm up the crowd, before President Nez and Edmund welcome Hammer and introduce Alien Weaponry. The room goes dark, and drummer Henry performs the family haka under a spotlight, eyes blazing. You wouldn’t want to face him in a war.

Intentions set, Alien Weaponry burn through PC Bro, Holding My Breath and Rage - It Takes Over Again, Lewis urging people to “let it out on this song”. They oblige with a slamming moshpit, and the catchy Kai Tangata prompts a wall of death. Since alcohol is banned on the reservation, there’s no bar, and all attention is on the music.

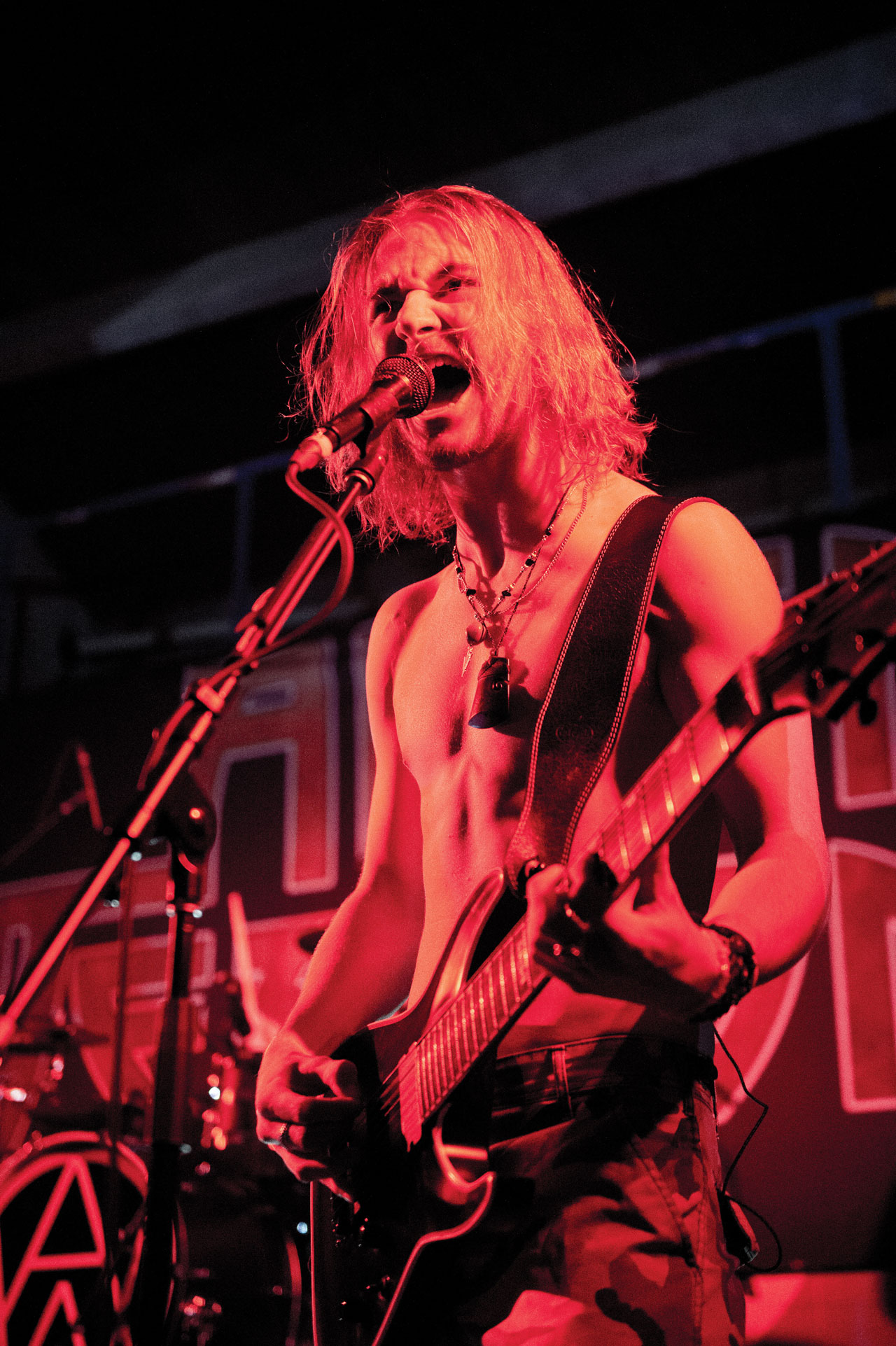

After the flag presentation, Lewis explains the context of Raupatu and everyone boos. Given the location, it’s a powerful moment. “We know you can relate to this message!” he shouts, getting them to chant the title. Then it’s on to closer R Ana Te Whenua, dedicated to their fallen ancestor, as a shirtless Lewis and Bobby primally prowl the stage.

It feels like we’re witnessing the start of something big. “I like their gritty sound, and I wanted to see them now because I hope they perfect it in a few more years and get even heavier,” enthuses punter Marty. Netelsha is impressed with their Mori lyrics. “Mixing their own language with the music? That was pretty bomb.”

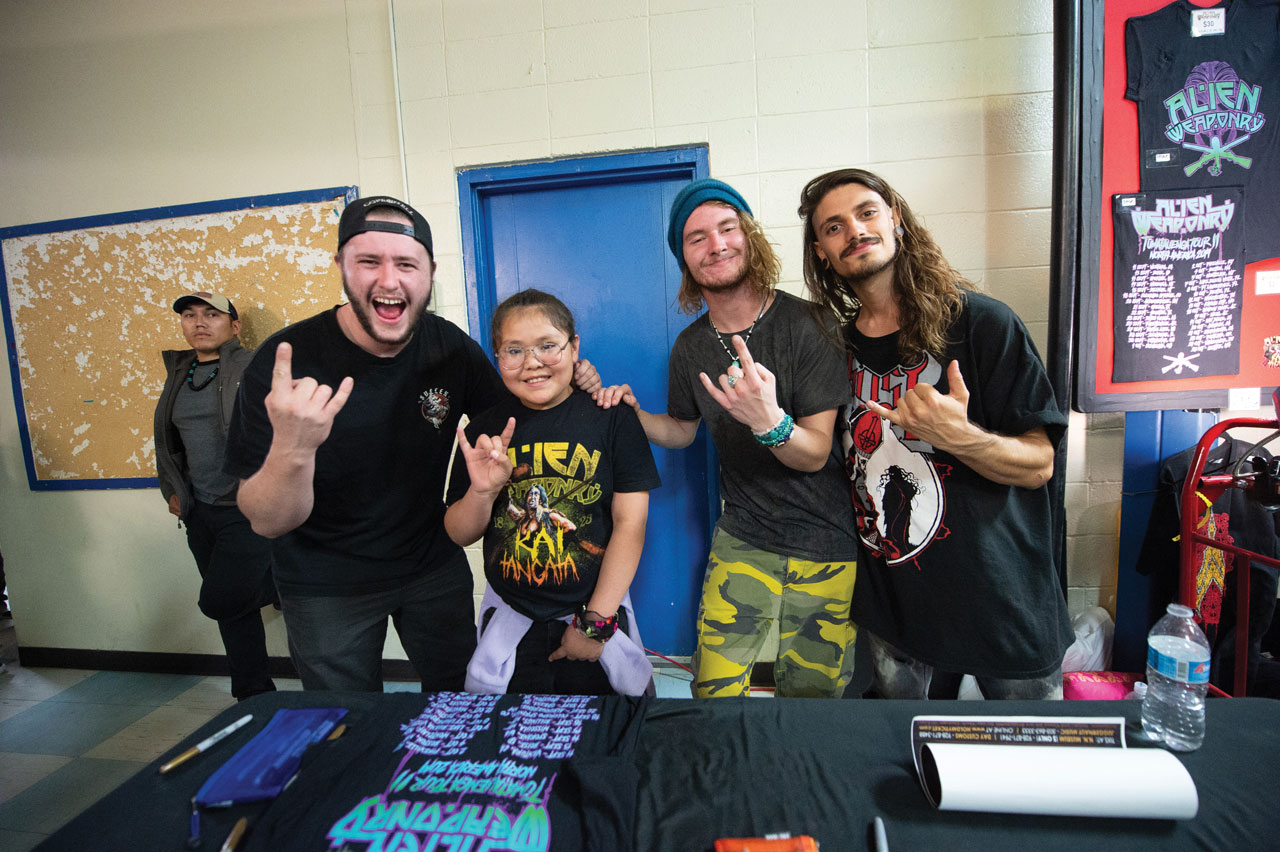

As the boys sign merch, we chat to promoter Randall. Holding the gig in a sports centre rather than a purpose-built venue has been tough – he had to rent the building, bring in a crew, hire the barrier and lights, and is operating at a loss. But for him, it’s all worth it to have the band back. “Look at these kids,” he grins. “They’re smiling, you guys enjoyed it, everybody enjoyed it.”

Sweating and dressed in bright camo trousers, Lewis looks like a young Max Cavalera. Unlike bassist Ethan, he’s given up school, and this is his life now. The kid who was teased for wearing a Lamb Of God t-shirt is following in Randy Blythe’s footsteps. He got into the band after seeing a video of them on Download’s main stage in 2007, and this year he played the very same spot.

It’s been a long day, and Lewis seems bewildered by the attention. In the long run he’d like Alien Weaponry to play stadiums, but for now he’s processing this tour. “The people in the States are hardcore when it comes to their music,” he marvels. “It’s surprising that people take the time to learn about this little band that’s based in the middle of nowhere, on an island, on the bottom of the world. It’s mindblowing.”

Eleanor was promoted to the role of Editor at Metal Hammer magazine after over seven years with the company, having previously served as Deputy Editor and Features Editor. Prior to joining Metal Hammer, El spent three years as Production Editor at Kerrang! and four years as Production Editor and Deputy Editor at Bizarre. She has also written for the likes of Classic Rock, Prog, Rock Sound and Visit London amongst others, and was a regular presenter on the Metal Hammer Podcast.