There are some questions for which there is only one appropriate answer. And when the question is: “Do you want to stay in a Butlin’s holiday camp in October and see Status Quo?” and – what’s more – it’s followed by a qualifying: “Chris Tarrant’s going…” only the irreparably jaded could possibly answer: “No”.

And so it was that a quoe of hacks, hicks, snappers, blaggers, chancers and other assorted undesirables including myself from ‘the media’ attempted to align itself with the edge of Platform Nine of Paddington Station. This took place at an hour of the morning situated closely enough to dawn to elicit dark threats of printed revenge against the unstoppably cheery PR crew who had spent weeks (maybe months) cajoling, carousing with and otherwise bribing the fourth estate with promises of luxury trains, champagne breakfasts, goodie bags and almost unlimited hedonism in deepest Somerset.

The PR people had a point. The proposition – Status Quo back on the holiday camp stage where they had met precisely a quarter of a century before, but this time with all of the pathos, bathos and nostalgia of their redoubtable career behind them – was a strong enough story to add a selection of tabloid journos, some bemused broadsheet boys, a couple of TV crews, a swatch of radio types and some comedy Germans to the usual skulking, sulky, spoiled suspects of the music mags.

Quo had the muscle and the money to lay on quite a spread. Everyone clutched a specially printed rail ticket, complete with directions to the platform’s edge. Humming gently trackside was not the usual British Rail rolling stock of a holed and winded tin can, but a superlative ‘special’, loaded with luscious livery, laden with top tuck and groaning crates of booze, and emblazoned with the ‘Quo Express’ logo beside every door.

A fleet of sturdy stewards, crisply turned out, disembarked to hold open doors and usher us aboard. In a British Rail first, everything ran like a Mussolini timetable. At nine o’clock precisely, we slid from the station as silkily as an otter returning to water, to looks of consternation and disapproval from the grey commuters.

Once aboard, everyone had a seat at a table bearing starched white linen tablecloths and sterling silver cutlery. In the middle of each, next to the flowers, was a magnum of champagne, chilling in an iced bucket. It was swiftly decanted by the stewards, and an excellent Buck’s Fizz was in hand before the Express had escaped the shadow of the station’s awnings. Before the phrase ‘a spot of breakfast would go down quite nicely right now’ had even been conceived of, let alone uttered, trolleys arrived tableside, holding glorious tureens of scrambled eggs, plates of smoked salmon and racks of buttered toast.

The volume levels, at first subdued, gradually raised and then soared. This wasn’t LA. This wasn’t Paris or Moscow or Budapest or any number of other intriguing destinations that those aboard were often sent to. The band was not Guns N’ Roses or the Happy Mondays or Sting or whoever else were the storied artists of the hour. But one thing was certain. By 9.30am on October 10, 1990, the Quo Express was the place to be. It was only 24 hours from, er, Taunton, but it was about as good as it gets.

By 1990, Status Quo were certainly in a position to celebrate. They had survived line-up changes. They had come through their ‘cocaine hell’. Francis Rossi had overcome having the middle of his nose drop out in the shower. They had been through divorce and declining sales and the awful death of Rick Parfitt’s infant daughter. They’d endured the iniquities of commercial decline and then, stoically, majestically, surmounted them. They’d had the glorious resurrection that began at Live Aid and that had taken in a new round of chart hits.

Now they were the favourites of toddlers and grannies alike; beloved of bank managers and bikers, school kids and headmasters; hardcore rockers and casual buyers bonding like never before in their enthusiasm for all things Quo-like.

They had come a long way. And as a new decade turned, they were savvy enough to realise that this history, and their unending, unique sound, plus the shimmer of household fame, could be parlayed into something rare among rock bands: the sort of enduring appeal of the British Institution. Like Rod Stewart, who they did a massive football stadium tour with in the mid-90s, like the Rolling Stones and Elton John, Quo might remain with us, immune to fad or fancy, for as long as they wanted to.

In the wake of Live Aid and their new-found acceptance as household names, Quo in the 90s meant a band that didn’t just rock all over the world but raised millions for the Prince’s Trust and other children’s charities. A band that gave concerts for the British troops in Berlin and went to visit prisoners in Pentonville. Above all, a band that performed at Radio One roadshows and appeared regularly in The Sun.

And the Quo Express, unbeknownst at the time to those aboard, was a part of that process; a symbol of where this quintessentially 70s band now saw themselves going, bigger and better than ever, in the 90s. In fact, it was the first and most original of a series of big press stunts that would keep the band high in the public eye for the next 13 years (and counting...).

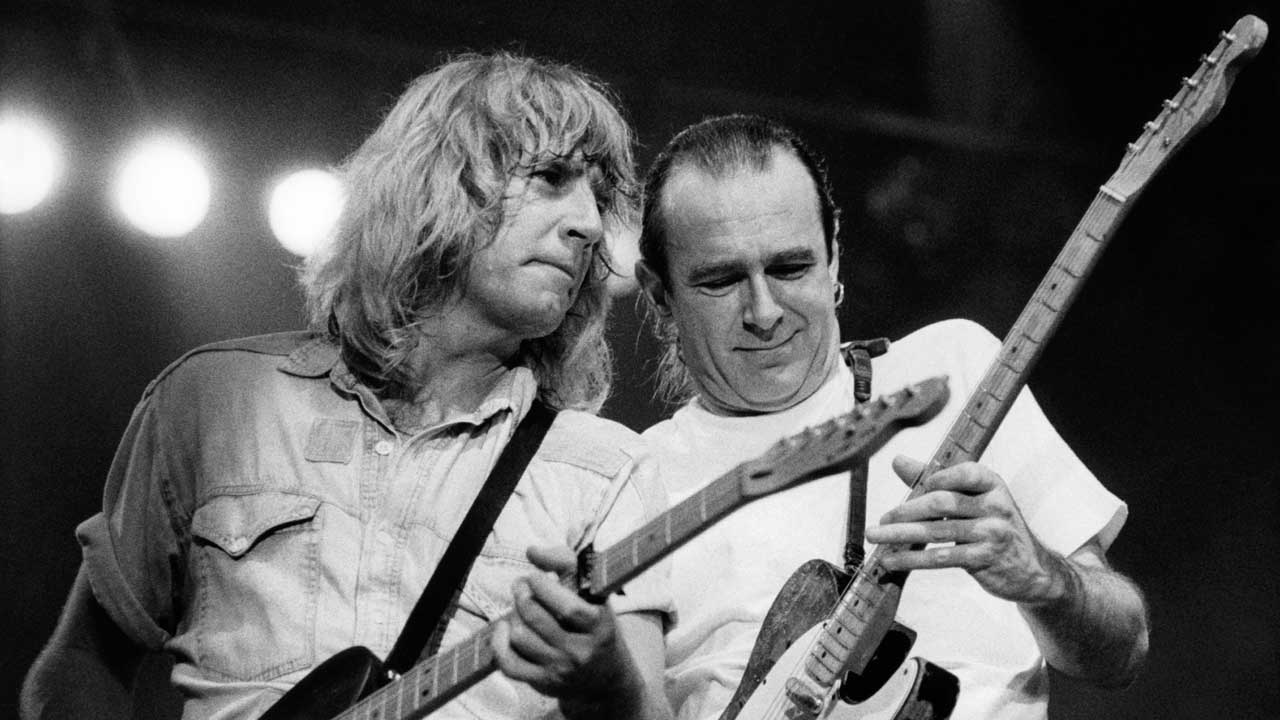

Parfitt and Rossi sat in a carriage towards the front of the train, holding regal court. Their traditional double-act – all wonderfully timed Carry On double entendres, amusing noises and Del Boy asides – was in full play.

Spirits were high. I remember someone asking them, “What’s the secret of happiness?” “What’s the secret of a penis?” Rossi replied. “A penis? Hmmm… what do you think, Rick?”

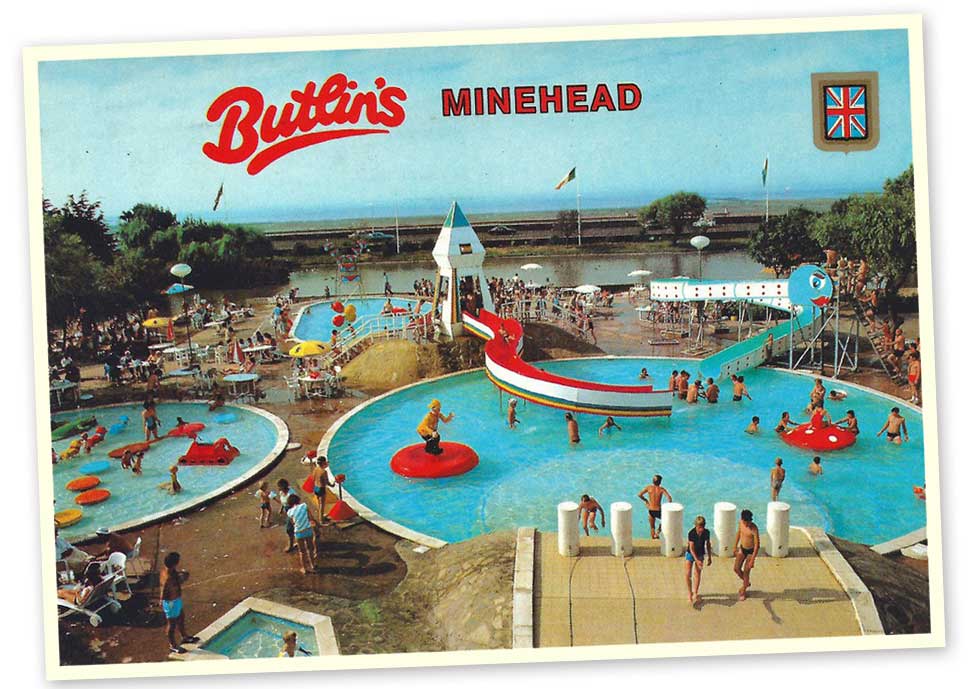

Slithering from Quo Express to bus for the last bit of the trip to Butlin’s holiday camp, Minehead, sober reality began to intrude. Locked behind a high white gate designed, apparently, to keep the patrons in rather than the public out, Butlin’s too, it seemed, was on the cusp of reinvention. Shaking off the last of its Hi-De-Hi high-camp image, but yet to grasp the full potential of fan-convention and teeny-bop tours that are its off-season staple today, Butlin’s back then was half two-star roadside hotel – with its cheery chalets replete with bunk beds – and half 1950s throwback, in the vestigial glamour of its faded ballroom and its deserted, desperate-looking Lido.

Allocated four-to-a-chalet by a legendary Redcoat, we walked in to find a lager-stocked fridge and a plastic, Quo logo-emblazoned guitar ready-inflated on the sofa. A note informed us that Butlin’s was now our playground. All of the attractions were free, all of the shops were open, lunch and dinner were laid on and Status Quo would take the stage of the Grand Ballroom that night at 9.00pm sharp. It didn’t say whether there would be a strict jeans-and-waistcoats dress code but we took no chances and got into our kit anyway. (Who doesn’t look cool in a white T-shirt and jeans?)

But before Quo’s performance, we went to see a performance given by Roy Walker, a comedian from the Bernard Manning school of political correctness made famous, briefly, back in the 70s by the same TV show that gave us Manning, Reed and company, The Comedians.

By nine that night we made damn sure we stood right at the front of the stage for Status Quo’s set, with the added luxury of a pint glass still in hand. The band played a show which, given our state and theirs (Parfitt and Rossi had admitted during the train journey that they would be ‘emotional’), every song seemed like a glorious encore.

When you’re in the mood to see Quo play live, they really are a wonderful sight to behold. They play everything you want them to play (Caroline, Whatever You Want, Rockin’ All Over The World, Forty-Five Hundred Times, Down Down etc.) and each song is like the ultimate terrace anthem – until the next one comes along. They are dressed exactly as you expect, they sound exactly as you would expect, and Francis and Rick still continue to whisper their mysterious thoughts to each other, as they have done for the last 35 years, throughout the show.

Afterwards, the Butlin’s disco opened. They played MC Hammer. Sure enough, you couldn’t touch it. If there had been a shop open selling the trousers favoured by MC – enormous black pantaloons that flared outwards from waist to ankle – they would have done a roaring trade. It was that kind of night.

The grey light of October reflected the following day’s mood. A thin rain fell. The Quo Express back to London again called early. Most bands – having had their cake – would have reverted to the ordinary train to relay their guests back to London. Status Quo didn’t. But then Quo have never been ‘most bands’; clearly, they weren’t about to reverse that trend in the 90s. The train was as superlatively well-equipped as the previous day‘s had been.

As cold hangovers were nursed and hot copy was prepared, the thought occurred that, whoever and whatever they might have been in their earlier, wilder years, Status Quo in the 90s were – above all else – nice people. Diamond geezers. And well rewarded for it, too. The Quo Express story made headlines all over the world, not to mention the main evening news on British TV that day. The trip is still talked about by those who made it.