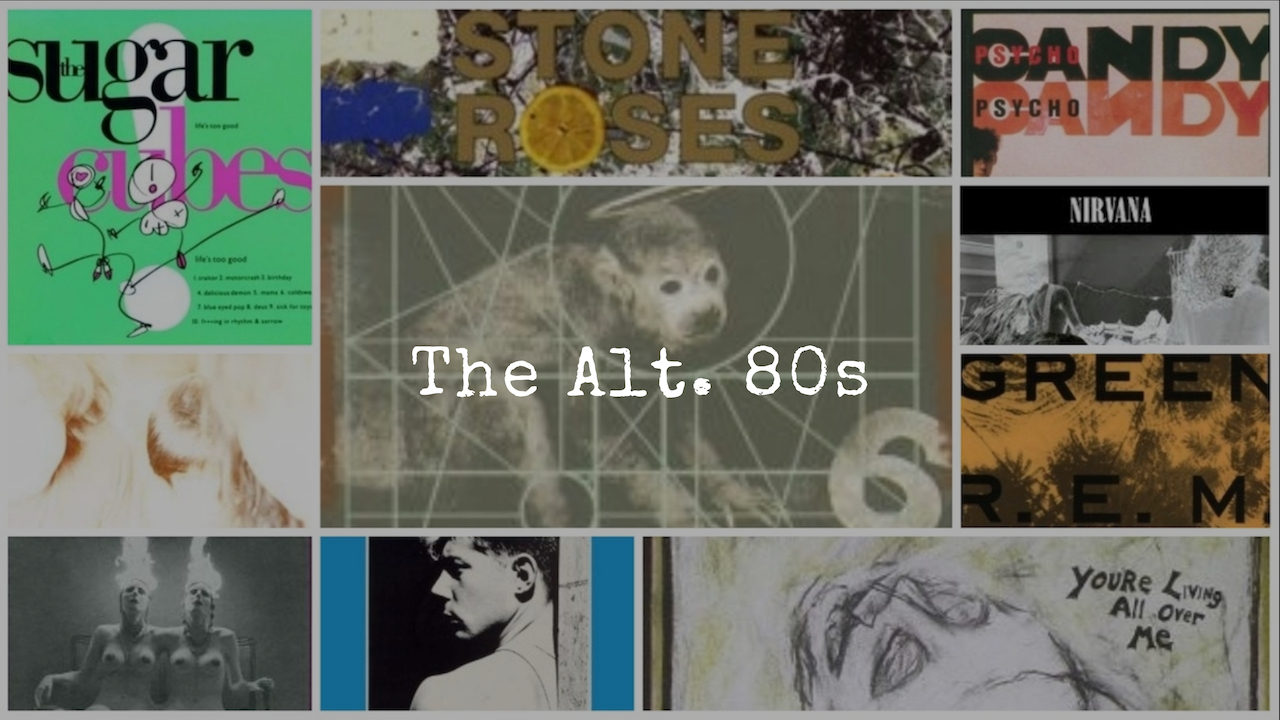

Alternative 80s: A guide to the best albums

From jangly indie to dark, sexy alt-rock, the 80s was the decade when there really was an alternative to the mainstream

Back in the mid-80s, ‘indie’ was a confusing thing: not a style of music, just an abbreviation. Literally short for ‘independent’, the ‘indie charts’ would be topped by the Jesus And Mary Chain one week (then signed to fledgling indie label Creation) and Kylie Minogue the week after (she was on the rather more established indie label PWL). Your typical cardigan-wearing Smiths fan would walk into their student union’s Nelson Mandela bar, quickly sign a petition pledging solidarity with the Sandanistas, before flopping on a sofa with the NME to read this month’s indie chart – only to discover that Inspiral Carpets had been kept off the number one spot by Rick fucking Astley! Where was the petition for that?

So indie kids were confused. They were happy being indie kids, but their charts were full of all these interlopers – manufactured pop stars who just happened to be on an ‘indie’ label. St Etienne’s Bob Stanley identified 1986 as the point where notions of indie were finally nailed: when the NME gave away a free cassette tape called C86. Featuring bands like Primal Scream (in their earliest and feyest incarnation), Shop Assistants, the Wedding Present, Weather Prophets etc, C86 began to define what ‘indie’ meant: jingle-jangly guitars, sensitive lyrics, floppy fringes, and an anti-rock aesthetic that expunged riffs, solos and macho posturing in favour of handkerchief-wringing sensitivity.

Towards the end of the 80s, and largely through a renaissance in American rock – bands like the Pixies, Dinosaur Jr, Jane’s Addiction – indie began to be known as ‘alternative’. Indie’s cardigan-wearing cosiness – the thing that had led entire nightclubs of students to sitting on the dancefloor when the DJ spun James’ Sit Down – had been replaced by something darker, sexier and much more rock. ‘Alternative’ was a more accurate title than ‘indie’: not only did it mean that not all bands had to be on an independent label, but it acknowledged the contrary nature of the alt-rocker. The unspoken truth was that indie/alternative fans liked anything, as long as nobody else liked it.

Bands grouped under the banner ‘alternative’ borrowed from punk, from metal, from country (in Dinosaur Jr’s case, all at the same time). As bands, they often sounded nothing like each other. What they had in common was a distain for the mainstream, even mainstream rock (then defined by Guns N’ Roses and Bon Jovi). It didn’t last for long, just making it out of the 80s to 1991, when the success of Nirvana’s Nevermind meant that the alternative had become the mainstream. It’s pretty much been that way ever since.

Pixies - Doolittle (4AD, 1989)

These days Pixies are best known as the band that Nirvana stole the old quiet-quiet-LOUD! dynamic from, but the truth is that the band’s second album should’ve been bigger than Nevermind. An explosive mix of pop hooks, deranged lyrics, surf guitar, murderous country music and a whole load of screaming, Doolittle was still accessible and infectious enough to make it more than some art piece. Debaser, Here Comes Your Man and Monkey’s Gone To Heaven filled indie disco dance floors for years to come while I Bleed and La La Love You were like pop songs written by Charles Manson.

Jane’s Addiction - Nothing’s Shocking (WEA, 1988)

Quite possibly the ultimate alt-rock band, Jane’s married a love of Led Zeppelin’s raunch with a feel for the soundscapes and textures of bands like The Cure and Bauhaus. Bassist Eric Avery was stylish and distinctive; drummer Perkins was a powerhouse; Dave Navarro could blaze as well as any EVH wannabe, but avoided cliche; Perry Farrell’s distinct voice and amazing lyrics defined them completely. If Ted... Just Admit It (about serial killer Ted Bundy and ending with the refrain “sex is violent!”) was intense, Mountain Song and Ocean Size were immense, while acoustic anthem Jane Says nicked it’s chords from Zep’s Over The Hills And Far Away.

The Smiths - Hatful Of Hollow (Rough Trade, 1984)

The Smiths’ best studio may be The Queen Is Dead, but this collection of singles and radio sessions is their most essential release. Morrissey’s miserablism and Johnny Marr’s amazing guitar playing nowadays seem as essentially 80s as flying pickets and the Falklands, but at the time they were a true oddity: genuinely original, consistently brilliant, and with an outrageous frontman. The cliche is that Morrissey is miserable, but these songs are full of wit and celebratory guitar playing. Songs like How Soon Is Now, and William, It Was Really Nothing make for a very English album to stand alongside the likes of The Kinks and The Who.

Stone Roses - Stone Roses (Silvertone, 1989)

If at first Stone Roses didn’t seem too distinct in an age that saw a multitude of indie rockers obsessed with the nailing the perfect Byrdsian pop song, one listen to closing epic I Am The Resurrection made you release that the Roses were a cut above, while She Bangs The Drums and Waterfall were pop classics. Blessed with one of the finest rhythm sections of the time (Mani and Reni), the band had real groove, while guitarist John Squire not only had the chops, he had a pristine guitar sound that sounded instantly classic. Singer Ian Brown was their only weak link – and he’s the only one who went on to have solo success.

Dinosaur Jr - You’re Living All Over Me (SST, 1987)

Dinosaur Jr have a compilation album entitled Ear Bleeding Country and that’s the best description you’re gonna get of their pre-grunge, um, grunge. Name-dropping Black Sabbath, Discharge, and with a vocal that owed a lot to Neil Young, Dinosaur Jr were a disfunctional three piece headed up by a slacker called J Mascis. Sounding like they couldn’t really be bothered playing you their riffy stoner rock, the Dinos long-haired anti-glamour had huge appeal in the days of ‘fake hair metal’ and bands who looked like they were trying too damn hard to please everyone.

REM - Green (WEA, 1988)

Like the indie and alternative scene they were so much a part of, REM seemed to get more and more accessible with every record. On Green you could actually hear what Michael Stipe was singing about (if not actually understand it) while the music was hookier, ballsier and less countrified than ever before. If Pop Song 89’s adaptation of The Doors’ Hello, I Love You for a more PC and less sexy age, was a bit like those 80s Bond films where he uses a condom, there was joy to be found in Stand’s infectious pop, portent in World Leader Pretend, while Orange Juice and Turn You Inside-Out rocked harder than they ever had.

The Jesus And Mary Chain - Psychocandy (WEA, 1985)

Fourteen songs of feedback drenched, honey-coated, heroin-chic’d pop in thrall to Phil Spector, Ramones, and the Velvet Underground, the Mary Chain were two fuzzy-haired brothers who discovered that the squalls of feedback they got when they rehearsed in their bedroom actually enhanced the songs. Such was the threat implicit in these otherwise sweet pop songs that, on tour, playing 45 minute sets with their backs to the audience, the Mary Chain provoked riots throughout Britain. Listen to this and you can see why for one brief moment they were talked about as the new Sex Pistols.

My Bloody Valentine - Isn’t Anything (Creation, 1988)

In 1988, floppy-fringed indie janglers My Bloody Valentine released a single called You Made Me Realise. Four pummelling minutes later, all of your preconceptions were shattered – and so were your ear drums. They didn’t put it on this, their second album, but it was cut from the same cloth: music that was trippy, sexy, scary. Guitarist Kevin Shields wrestled with a heavily-treated guitar sound, wringing melodies from feedback and conducting choirs of distortion while male and female vocals drifted over each other hypnotically. Somehow the shoegazing movement was born from this.

Sugarcubes - Life’s Too Good (One Little Indian, 1988)

Even in the world of alternative rock the Sugarcubes were weird: a six piece band of Icelandic pixies and nutters called stuff like Magga Örnolfsdottir and Bjork Gudmündsdottir, playing songs about girls with spiders in their knickers and Gods with sideburns. While the rest of alt.rock looked to the dark side, Bjork and co. were celebratory, sexy (Life’s Too Good?!) and armed with one of the best singers of the decade. Live, they were a riot and this debut caught some of that verve in the bouncing Birthday, the mad Deus and the wise Fucking In Pain And Sorrow (lyric: ‘You should take the pain and sorrow and turn it into power/Life’s both sweet and sour’).

Nirvana - Bleach (Subpop, 1989)

No-one spotted it, of course. Nirvana were just another one of those ‘Subpop bands’ - decent enough, but you didn’t rush from the bar when they were support. Three years later, everyone went scurrying back to Bleach to see if there were signs they’d missed. There were plenty: Love Buzz, About A Girl, Blew – all laid down the blueprint for Nevermind. Negative Creep was a new punk classic - and actually quite funny until you realised he really meant all that “I’m a negative creep when I’m stoned” stuff.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.