When British blues rockers Ten Years After flew in to the Woodstock Festival by private helicopter on August 16, 1969 they weren’t unduly impressed by the 500,000-strong crowd marinating beneath the Catskill Mountains.

“It was just another day on the date sheet,” said Ten Years After’s then frontman Alvin Lee. “We’d already played huge festivals [Bath, Newport, Maryland], and once the crowd reaches a certain size it makes no difference – the horizon just goes back further.”

Even so, nerves began to fray backstage as Lee and bandmates Leo Lyons, Ric Lee (no relation) and Chick Churchill realised they may have to go on in the middle of a storm. Sensing their discomfort, others on the bill such as Janis Joplin, Joe Cocker and Country Joe McDonald tried to wind them up.

“Everybody was saying: ‘Tough luck – looks like you’re going to be electrocuted,’” Lee recalled. With typical downbeat Nottingham wit, he replied: “Yeah. And think how many records we’ll sell if I die.”

There was another, more urgent problem: “They’d run out of ciggies backstage so I volunteered to go out in the audience and blag some. The first people I met were two coppers who said: ‘We haven’t got any, but you can have these joints.’ I said: ‘You’re police!’ Their answer was: ‘If you can’t beat ’em…’ I came back with 30 joints, so I was quite popular.”

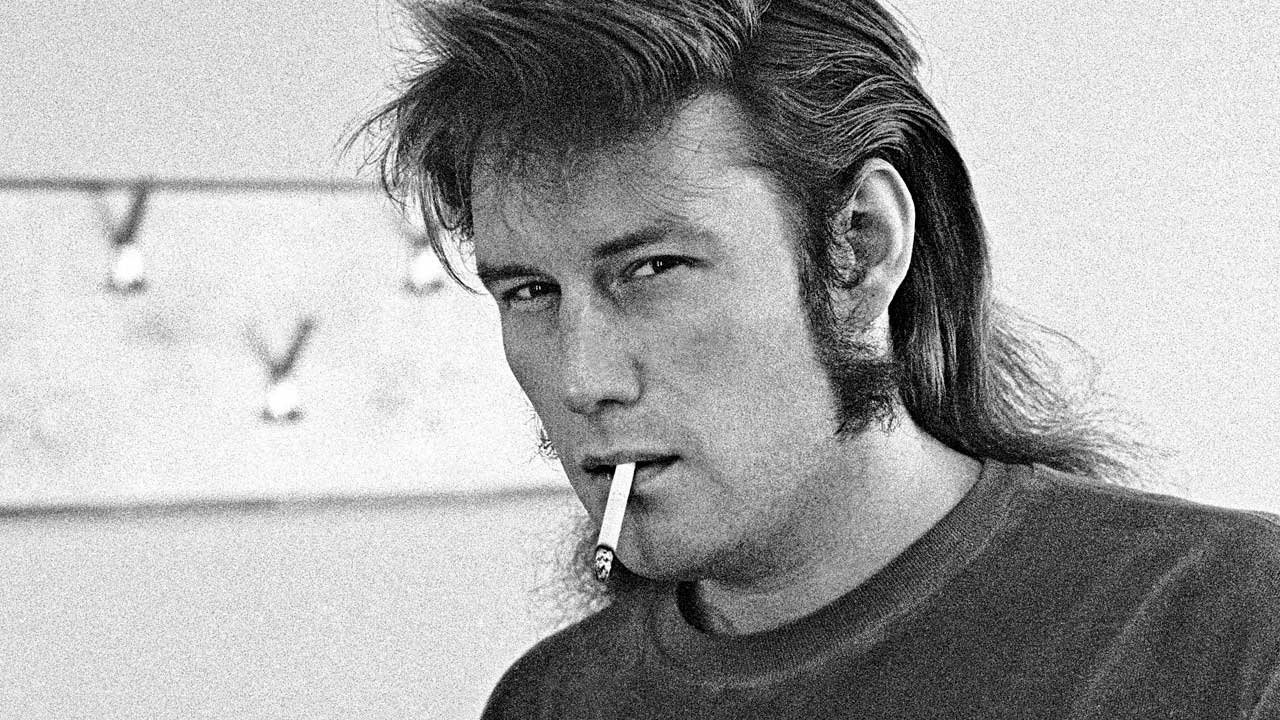

As part of the British Invasion of hard rock blues groups, Ten Years After were somewhere near the top. And though history dictates that they were never considered as cool as Cream, the Jeff Beck Group or Led Zeppelin, Alvin’s monikers (Captain Speed Fingers, The Fastest Guitar In The West) guaranteed him kudos. When the Woodstock movie of the festival came out a year later, Ten Years After’s showstopper I’m Going Home thrust the band towards superstardom, even though the studio version had flopped when released as a single from the excellent Undead live album.

A year earlier, Ten Years After were playing that number in little clubs like Klooks Kleek in West London. Now, Michael Wadleigh’s film (edited by Martin Scorsese) had their mugs on cinema screens worldwide, performing a boogie blues that rehashed every cliché in the book and seemed to have taken about five minutes to write. In any case, it was a great time to be British in America. “There was competition because of Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, but there was room for everyone. It felt like we were taking over,” Lee recalls.

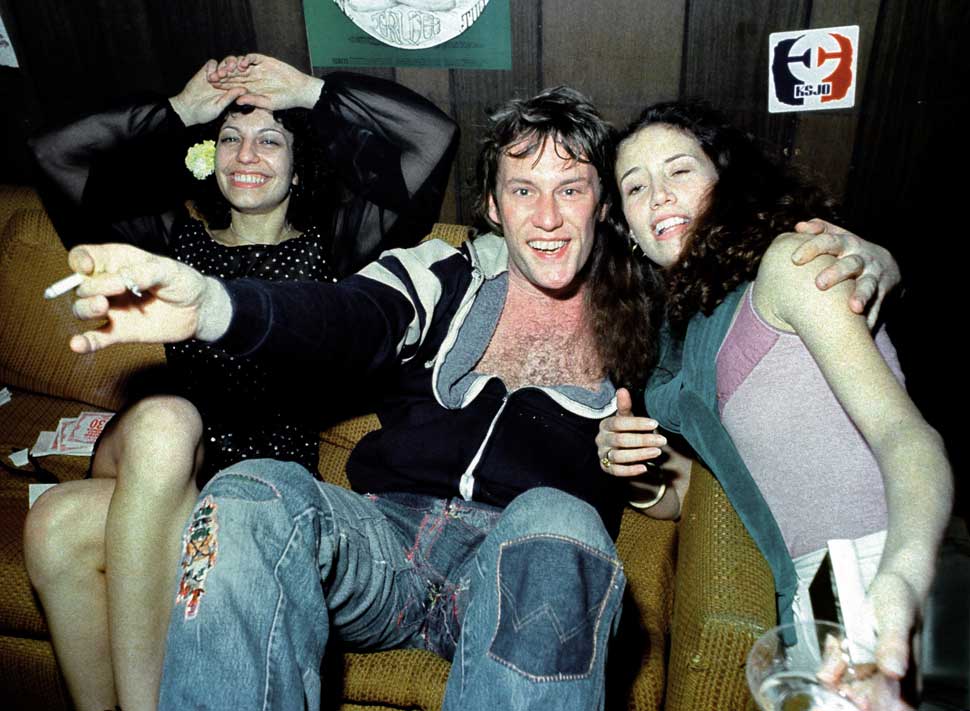

As the Brit boys drank, pilled and whored their way across the USA, high jinks were inevitable. At New York’s Singer Bowl in July 1969, Lee, Beck, Page and Ron Wood were joined by John Bonham, Tony Newman, Glenn Cornick, Robert Plant and Rod Stewart for a riotous nine-man jam version of Jailhouse Rock that descended into an orgiastic version of The Stripper.

Someone threw a glass of orange juice at Lee, while the Led Zep drummer removed all his clothes. According to Rod Stewart, “it was fuckin’ incredible. I finished the whole thing off by shoving a mic stand up Bonham’s arse and he got arrested. The cops pulled him off, while I ran away. We were all pissed out of our heads.”

Some say it was Bonham who chucked the juice at Alvin. More likely it was Jeff Beck. He certainly takes responsibility. “I threw a mug of orange and it stuck all over his guitar. It was one of those animal things. Three English groups at the same place have to add up to trouble.”

From then on, every time Ten Years After, Jeff Beck and Led Zeppelin shared a stage, there was trouble. Food fights became fistfights as the roadies took turns stripping the musicians and leaving them tied up and stark bollock naked by the speakers. Probably wisely, Lee blocked this period out of his memory. “I’m sure that never happened,” he said.

Ten Years After capitalised on their success – at a cost. “We did 27 American tours in seven years – a record. Then we’d get home and management would tell us: ‘We’ve booked you in the studio and they hope the songs are ready.’ They weren’t. ‘So write on the road!’ That was impossible.”

If the first two albums came easily to Alvin, who’d been a graduate of the Hamburg Star Club scene in 1962 as a member of The Jaybirds, the constant pressure to deliver became a chore. Luckily, stimulus was at hand when they delivered the Stonedhenge, Ssssh, Cricklewood Green and Watt albums to their label, Deram.

“I took LSD in San Francisco in 1968 and found it very illuminating,” said Lee. “We played with the Grateful Dead in Phoenix and they had a very interesting attitude. They’d go off stage [during Dark Star] and leave their instruments against the amps, feeding back. We started experimenting. Stonedhenge slipped under the radar, despite its title. The press didn’t seem to notice that the cover had pictures of hookahs, pipes and smoke on it. We were taking a lot of hallucinogenics and made weird albums, and I was all for that. But the writers glossed over it all – how terribly British.”

Cricklewood Green seemed to have an innocuous title, but it referred to a local dope dealer’s smoking requisites. While Lee’s blond good looks and well-built physique threw a naïve press off-guard, Ten Years After were actually smoking, tripping and boozing for Britain. “It was all good for the creative juices,” he said. “I’d been in Hamburg just after The Beatles, with the gangsters and prostitutes, and I had the run of the Reeperbahn as a teenager, so I wasn’t naïve when it came to sex, drugs or rock’n’roll.”

By the early 70s, too much fun was becoming dangerous. “Downers and alcohol weren’t a great combination. The LSD was always good stuff, but I was in danger of joining the dead-before-30 club. I once woke up backstage with the roadies throwing water over me because they thought I was dying. The pressures of the road are what you want initially, but when you’re the frontman everyone is relying on you to deliver.

"It was a band, yet I was taking all the responsibility, and I never enjoyed that. By 1972 I was overdone. We’d had eight good years, been very tight-knit, and suddenly there was a lot of internal friction; people weren’t talking much. They moaned about me getting all the publicity. So I said: ‘You do it, then.’ Trouble was, interviewers didn’t really want to talk to Chick Churchill. It became petty. At gigs they’d sell T-shirts with my face on, and they got very pissed off. Understandable, I suppose.”

Having craved a kind of fame, when it came Alvin found it wasn’t to his liking. “I didn’t like recognition. Maybe it was because I was an early doper, so I was obsessive about keeping a low profile. Maybe I was paranoid. Rod Stewart loved the attention, but it made me tentative because I was always carrying dope. I bumped into The Who on the road and Keith Moon was doing the usual – throwing cherry bombs out the hotel window at police cars and smashing the place up.

"Of course, they raided the room and I was terrified. When you’re carrying dope you don’t throw televisions out of windows, you sit down quietly and get stoned. Drugs didn’t help the problems in my head, and there was no rule book on how to be a rock star. I got a bit lost.”

Exhausted by the demands of Ten Years After, Alvin bowed out before the release of their final album, ironically named Positive Vibrations. Buoyed by his own status, he had already been plotting an escape route. “I was starting to get a reputation as a difficult so-and-so with the band and with the press. It was probably true, but I was so bored of Ten Years After. I’d play badly and people would tell me I was great. My sanity became relative, and I was heading down the wrong path, mixing with some terrible types.”

The wake-up call arrived when Lee went for dinner with a top New York lawyer. “He sat there and said: ‘I can give you anything you want. Do you need more cocaine? Do you want me to have someone bumped off? I can arrange that. Whatever it is, Alvin, just give me a call.’”

He already had the money, the showbiz cars and the nice house in the Rockbroker Belt. “And I still woke up dissatisfied. Luckily I met Mylon LeFevre from the band Holy Smoke and we made the On The Road To Freedom album, mixing my English with his country and Atlanta southern rock stuff.”

LeFevre was a consummate hustler whose gospel song Without Him was covered by Elvis Presley when Mylon was 17. He spent his royalties on fast cars and heroin, and had just come through a withdrawal programme when he teamed up with the equally frazzled Lee in 1973. Decamping to George Harrison’s home studio, the unlikely duo gathered together a superstar cast.

“Mylon went to the Speakeasy and came back with Steve Winwood, Mick Fleetwood and Ronnie Wood. He blagged them. ‘Hey, man, come and play. You don’t need any money, you’re musicians.’ And they fell for it. That’s when I met George [Harrison]. It was quite a band. We did a gig at Biba’s in London, and on the way down from my house in Hook End in Oxfordshire, Steve Winwood and me got smoked up in his Ferrari in the middle of a downpour, during which his windscreen wipers fell off. He was so stoned he wanted to stop on the A40 and find them.”

With his royalties flooding in, Lee made sure he enjoyed the rock star life, living in a 17th-century mansion complete with minstrel gallery, near to the Prime Minster’s country residence, Chequers.

“I became part of the Thames Valley gang of musos: Jim Capaldi, Jon Lord, Mick Ralphs, Dave Edmunds… and George Harrison. He became the friend who would drop by and play slide. He contributed the song So Sad (No Love Of His Own) – Harrison’s only known break-up lament for Patti Boyd after she left him for Eric Clapton – which I think is one of his best ever songs. He’d call me at 1am just to jam. I was his after‑hour’s friend, rather than the showbiz or racing car pals. He had all this equipment that Jeff Lynne gave him, and we’d sit around playing Shadows tunes.”

While the idea of a permanent supergroup didn’t appeal to Lee, he was happy to be part of the Pishill Artists, an impromptu bunch of wealthy rockers who would turn up on the quiet to play at the Crown Inn in Pishill for delighted locals. “George and I spent five days a week together, at mine or at his in Henley, Friar Park. A lot of it was just cracking jokes. He asked me what I thought of Eric Clapton. I told him: ‘Too much blood in the drug stream.’ Which cracked him up. We wrote songs like The Bluest Blues, but mostly we just hung out.”

Years later, Alvin sold his Hook End house and studio to Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour and moved to a spread at Woodcote in Buckinghamshire, but the two maintained their friendship. For his own reasons, Lee didn’t attend Harrison’s funeral.

“I don’t do funerals, they’re too depressing,” he explained. “It was awful when George was stabbed. We called that the Friar Park Murder, because although he died of cancer, after that incident [on December 31, 1999, when Harrison suffered near-fatal wounding at the hands of a knife-wielding intruder], he was never the same again.

"The last time I saw him he had SAS men patrolling the grounds. It was horrible. When I left Britain to live in Marbella, he accused me of deserting him. He broke down and said: ‘I’ve only got Jim Capaldi left!’”

Alvin Lee lived out his last days in a kind of exile from England in an area outside Marbella. “I don’t miss it," he said. "Don’t miss the speed cameras. I got into financial difficulties when I left Hook End [he also got divorced]. My outlay was more than my income, and a ton of money disappeared, to the point where I started playing club gigs for £1,000 a night in ’89 because I could see the bottom of the barrel. Any money I had, I made from buying and selling property. I also sold everything else when I left England. I put all my Woodstock memorabilia, my gold records and my guitars into auction. I don’t have any of those possessions left.”

For years as a solo artist he refused to play old Ten Years After favourites such as Love Like A Man and I’d Love To Change The World. “I was a bit mean to the audiences. I don’t care so much now, because some of those ancient songs sound like old friends.”

He didsn’t mind his albums, although his star waned when the new wave swept bands like Ten Years After into a cul de sac. “I made a couple of less good ones, like Free Fall and RX5, trying to be radio-friendly then finding they didn’t have any takers.”

Still, in southern Spain the weather was good and the wine was cheap. Alvin released a new album out called Still On The Road To Freedom in 2012, and a compilation of “my up-tempo stuff called The Best Of. It’s daft they’re out at the same time, but that’s not my decision. I’m fed up with all the ‘legendary Alvin Lee’ stuff. ‘Bullshit’ is a strong word, but that’s probably what it is. I think I’m lucky, because whatever I strived for I usually got.

"I’m just a musician, really. I’m not that valuable. Am I stubborn? Dunno. I’m still dedicated. I still play guitar every day, at least two hours. I’m not as fluent as I was until I play live, and then it starts to flood back. At least I’m not a travelling jukebox any more. I do what I want and I please myself and my wife Evi.”

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 178, in December 2012. Alvin Lee died on March 6 2013, after suffering complications during routine surgery to correct an abnormal heart rhythm. The fastest guitarist in the west had finally gone home.