"You’re under the misapprehension that I know what I’m doing,” chuckles Leon Russell, the 72-year-old singer, songwriter and pianist with the white Stetson hat, long, white hair, white beard and lived-in face. “But I had absolutely no idea what I wanted to do with this new record, then Elton said: ‘Get in a producer.’ I don’t usually work with a producer on my own records, but I got in Tommy.”

The record in question, Life Journey, maps Russell’s musical evolution from crack session keyboardist with LA’s Wrecking Crew to musical director with Joe Cocker, and solo artist on his own Shelter label, through 10 cover versions and two original songs.

Elton, meanwhile, is Elton John, who calls Russell his “hero”. John helped return Russell to the US chart for the first time since 1979 with 2010’s T Bone Burnett-produced The Union, which John sung and played piano alongside Russell on. He is listed as executive producer on Life Journey. Finally, Tommy is Tommy LiPuma, who has produced Miles Davis, Dr John and Peabo Bryson, to cherry pick just a few names over the years, and first worked with his pal Russell on the O’Jays’ 1965 hit Lipstick Traces for Imperial; Russell was playing piano. “I don’t remember that,” says Russell, “although I do remember when we first met. He was a promotions man at Liberty and I was there making demos with Jackie DeShannon and Sharon Sheeley.”

Tommy was instrumental in Life Journey’s making. He picked the songs, like Haven Gillespie and Beasley Smith’s That Lucky Old Sun, Duke Ellington and Paul Francis Webster’s I Got It Bad & That Ain’t Good, John Davenport and Eddie Cooley’s Fever and Mike Reid’s Think Of Me. He also recruited the musicians including Californian blues guitarist Robben Ford, erstwhile Count Basie collaborator John Clayton and Oscar Peterson cohort Jeff Hamilton. On top of this, he also chose the studio – the album was recorded at LA’s Capitol Studios with engineer Al Schmitt.

“Tommy was great,” says Russell, “just about the best producer I’ve ever had the pleasure to work with. We just went into the studio, two old guys together, and messed around making music.”

Russell has, to use his phrase, been messing around making music from an early age. Born Claude Russell Bridges in Lawton, Oklahoma on April 2, 1942, he started playing classical piano aged four and at 14 was helming bands including the Starlighters with a line-up completed by guitarists JJ Cale and Leo Feathers, drummer Chuck Blackwell and saxist Johnny Williams. “I was still at high school,” he says, “playing standards in supper clubs and piano bars and rock ‘n’ roll in nightclubs. By the age of 16, I knew this was what I wanted to do. I didn’t see it as work, and I never wanted a real job so it fit real well.”

The standards he was playing he learned from listening to big band records. “I saw an ad for the Columbia Record Club, it was sign up and get six records free, so I did that, and for some reason I picked the big band category. I started to listen to Benny Goodman, Miles Davis, JJ Johnson, Kai Winding. It was an education.”

Sam Cooke was also pivotal in his musical upbringing. “I got the You Send Me single. On the back was his version of Summertime and I wore that side out playing it so much. It blew my mind. I think he’s the greatest soul singer of all time. I got to work with him on a session produced by Don Costa. It was great to be in the studio with someone who I admired so much. Bobby Womack was on guitar.”

Another influence was Jerry Lee Lewis, who Russell went on tour with after graduating from Will Rogers High School in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Russell remembers: “One night in Cheyenne, Wyoming, Jerry Lee was stood on the piano bench, watching some people in the audience fighting, and they started climbing up on stage. The curtains came down and we grabbed our instruments and ran to our cars and got out of there as fast as we could.”

It was advertising not music, though, that took Russell to Los Angeles when he was just 17. A love of Stan Freberg’s funny ads for the radio led to the belief he could make it in the same field. “It didn’t work out that way. The ad business was not very tasty. So I started playing on people’s records instead. I didn’t know how long it would last but it gave me the money to buy dinner, so I could live. I didn’t have many expectations, which was to my advantage.”

Russell can’t remember how he got started doing that, but soon he was playing on demos with the aforesaid Jackie DeShannon and Sharon Sheeley. “Jackie introduced me to Jack Nitzsche and I started working for him.” Nitzsche was the producer Phil Spector’s right-hand man, and Russell landed sessions playing piano with The Ronettes. He contributes to the wall of sound on 1963’s Be My Baby and Baby I Love You. “I studied Spector. He had such confidence in the studio, he was unique in the way he worked.” He also performed in the studio with the Beach Boys (“Brian Wilson was in charge”), The Byrds (“Producer Terry Melcher is incredible”) and Bob Dylan (“The best songwriter”). But it was Aretha Franklin who impressed him most. “I worked with Aretha at Columbia, there was one session when she cut Am I Blue? with a big string section and at the end of the song, they all tapped their bows on the music stand. I wasn’t used to seeing that much excitement from a string section,” he deadpans.

As part of the Wrecking Crew, an LA collective of session musicians, Russell provided the back-up on 1964’s The TAMI Show, and scored his first songwriting hits with Gary Lewis and the Playboys. 1965’s beaty Everybody Loves A Clown hit the US number 4 in 1965 and the similar-sounding She’s Just My Style number 3 later that year. His breakthrough proper came four years later, though, when Joe Cocker included the deeply soulful Russell-scribed Delta Lady on his 1969 eponymous album produced and arranged by Russell that hit the US number 11 spot. “Denny Cordell, who produced Procol Harum’s A Whiter Shade Of Pale, was in the States looking for a US distributor and heard me on a Delaney and Bonnie record,” explains Russell. “He was cutting Joe Cocker at the time, and he got someone to call me up and ask if I’d like to play on Joe’s album. After I got to play on the album, well. I had written a couple of songs, one of them Delta Lady. I thought I’d play it to Denny and see what he thought.” Denny liked it and Russell was recruited, and hired as bandleader, arranger, piano and guitar player on Cocker’s 1970 Mad Dogs And Englishmen tour. The same year, Russell struck out on his own taking the spotlight on his self-titled debut solo record.

The album, recorded at London’s Olympic Studios in 1969, was engineered by Glyn Johns and produced by Russell and Cordell. A gorgeous mesh of gospel, country and soulful blues, it immediately established him as an artist in his own right with Russell’s definitive take on Delta Lady and the yearning piano ballad, A Song For You, which has since become a bonafide standard. “My intention,” he says, “was to write a song that anybody could sing.” Artists as diverse as Ray Charles, Andy Williams and Amy Winehouse are just a few who went on to cover the song.

“It was really exciting cutting the record,” remembers Russell. “I said to Glyn Johns how Eric Clapton would sound great on a song and Glyn said, ‘I’ll call him up.’ The next thing I knew Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Bill Wyman, George Harrison, Charlie Watts and Ringo were playing on my album. Glyn was the best engineer I had worked with at that time, it was great fun and an all-new experience for me.”

The album was issued on Shelter Records, Russell’s label with Cordell. “I started my own label primarily because I had trouble getting on anyone else’s,” he laughs. “I told Denny I had always fancied having my own label and so we did Shelter together.” Via Shelter, which Russell spearheaded until 1976, leaving after a falling out with Cordell to found Paradise Records, Russell gave a platform to former Starlighter JJ Cale, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and Freddie King.

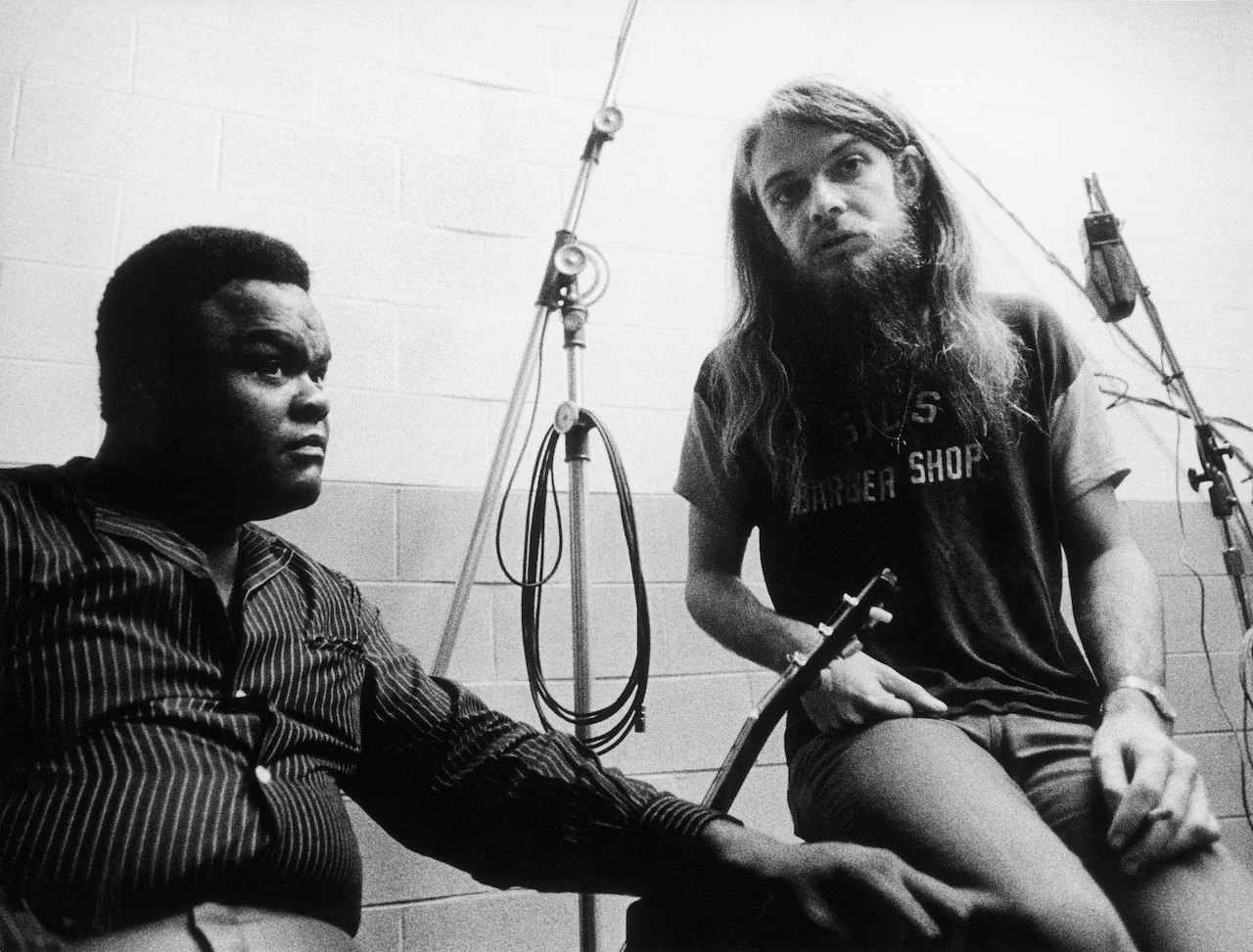

Russell explains of the latter’s recruitment: “Denny handled the day-to-day running of it, the record company aspect of it, and one day he asked me, ‘Is there anybody you’d like to make records with?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, I’d like to make records with Freddie King.’ Because when I first went out to California I got interested in playing the guitar and I listened to one of Freddie’s records over and over because I wanted to learn how to play like him. So Denny called up Freddie, and the next thing you know I had Freddie King in the studio and we ended up cutting three records together.”

The first, 1971’s Getting Down, featured covers (a countryish take on Elmore James’s Dust My Broom, and straight-ahead takes on Eddie Boyd’s Five Long Years and Big Bill Broonzy’s Key To The Highway) and originals penned by Don Nix (the Hendrixy psych-rock blues of Going Down, the Ray Charlesy R&B ballad Same Old Blues). “Denny had the idea to fly us down to the former Chess Records studio in Chicago, he thought it would be good. But I found it to be a substandard studio compared to the one I had in my house. Chess was antiquated and difficult to work in, that’s what I remember about that session the most.”

The same year also saw the release of Russell’s second solo album, the gold-selling Leon Russell And The Shelter People, a celebrated appearance as a soloist and as musical director of George Harrison’s band at the Concert For Bangladesh, which was organised by Harrison and Ravi Shankar and held at New York’s Madison Square Garden; and a guest spot on B.B. King’s Indianola Mississippi Seeds album. Recorded at LA’s Record Plant, it included King’s reworking of Russell’s Hummingbird, arranged by Russell. Russell also played on the tracks Ask Me No Questions and King’s Special. “That was very exciting for me, I was sat at home watching TV and B.B. King’s office called up and said he was going to cut one of my songs and they wanted me to come and play on it. He was the first player of that style that I ever heard. I asked him, ‘How did you get your guitar to sound like that?’ He said he was trying to make it sound like a steel guitar.”

Russell remained in demand throughout the 70s; his 1972 self-penned B-side, This Masquerade, made the US Top 10 when covered by George Benson – LiPuma produced Breezin’, the album it is culled from – in 1976. It also landed Benson a Grammy for Record Of The Year. Russell made number 1 himself on the US country chart when he teamed with Willie Nelson on a cover of Heartbreak Hotel in 1979; its parent album, One For The Road, made number 3 and secured Russell his seventh gold record. While the 80s, 90s and 2000s brought little commercial acclaim, Russell continued to release records on an almost yearly basis and toured them to a devoted audience.

Then in 2009, he got a call from Elton John. He wanted to make a record with Russell of new songs written by them together. The result, The Union, hit the US top 5. John and Russell first met in 1970 when Russell checked out John’s show at the Troubadour in Los Angeles. Impressed with what he saw, he took John on tour with him as his opening act. “Elton raised my profile with The Union,” he says. “And he paid for this album to be made before I got a deal with anybody. I’ve got a lot to thank him for.”

Just one listen to Life Journey and you see why John had such faith in Russell. The choice of material is impeccable. “In our preliminary meetings, I’d just be playing stuff I knew to Tommy on the piano and he’d say, ‘Yes, I like that, let’s try it. That’s how we chose That Lucky Old Sun and [Robert Johnson’s] Come On In My Kitchen.”

The first named, the stand-out on the album, becomes a powerful spiritual in Russell’s hands. It’s poignant, heartfelt, with warming Hammond B3 organ (played by Larry Goldings), pedal steel guitar (by Greg Leisz) and gospel vocal harmonies. It casts Russell as the preacher crying out, “Won’t someone come and help me?” during a rousing call and response. The song also features Robben Ford on guitar. “I don’t know much about him,” admits Russell. “It was Tommy’s idea to get him in. But we had cut the song and we felt it just needed something else. Tommy said, ‘I know, let’s get Robbie in.’ So we sent him the tape and he went to work on it.”

On Come On In My Kitchen, meanwhile, Russell is captured rough and raw. His voice, a sandpaper growl, recalls Johnny Guitar Watson at DJM at times, and is pinned to a sparse background provided by a band comprising bassist Willie Weeks and drummer Abe Laboriel Jr. “It was Eric Clapton who introduced me to Robert Johnson’s music first,” he recalls affectionately. “I was in England visiting George Harrison, I don’t remember why I was there, but we ended up at Eric’s house and he played it for me. I was quite taken with it.”

Other songs weren’t so familiar to Russell, though. “A lot of the songs I played for singers, but never sung on my own,” Russell says. “So a lot of them were surprises, songs I really had to learn – the take of The Masquerade is Over is only the second time I ever sang it; once on the demo and once on the session. With some of the big band stuff, I was reading the charts, learning the words, watching the conductor – it’s an experience to do all that stuff.”

Herb Magidson and Allie Wrubel’s I’m Afraid The Masquerade Is Over tips the hat to Russell’s own This Masquerade. Draped in a velvety orchestral arrangement, it’s a widescreen melodrama of Douglas Sirk proportion, with Russell’s croak throbbing with a drunken-like sorrow and woe. The band – drummer Jeff Hamilton, arranger and bassist John Clayton, guitarist Anthony Wilson – execute blues with a feeling perfectly. Clayton and Hamilton also lead the Clayton Hamilton Jazz Orchestra utilised on Hoagy Carmichael and Stuart Gorrell’s Georgia On My Mind.

“I’ve listened to that song all my life,” says Russell, “and I was imagining a Count Basie-type orchestra playing on it.”

So Tommy put in a call to Clayton, who had arranged Basie from 1977 to 1979. Hamilton also has an impressive jazz pedigree, having played with Basie, Oscar Peterson, Ray Brown and Ella Fitzgerald, too. “It was a daunting experience to play in front of those guys because they are real icons of jazz, and I’m a talented illusionist and not really a jazz player at all. So it was pretty challenging but I learned a lot.”

Russell’s reimagining of Georgia On My Mind is another of the album’s emotional peaks, beginning with just Russell at the piano with brush drums, before breaking into a full big band affair arranged by Clayton.

The first of the two originals on the album, meanwhile, couldn’t be more contrasting. Big Lips is a risqué boogie. “I was so hard I just had to unzip and get a taste of those sweet lips,” he sings lasciviously. “My kids told me not to send that one to Tommy,” Russell laughs, “they said it was too dirty. After Tommy heard it, he called me and he was screaming with laughter down the phone – he said: ‘We got to do that!’”

The second, Down In Dixieland, is a carnivalesque paean to Louisiana Dixieland jazz arranged and conducted by John Clayton, with a band including Ira Nepus on trombone, Darrell Leonard on trumpet and flugelhorn, and James Gordon on clarinet. Few musicians create their best work in their twilight years, but that’s just what this septuageran has done with Life Journey.

“To repeat what I said at the beginning of our conversation,” he says, “you’re under the misapprehension that I know what I’m doing and I really don’t. I don’t know what motivates me – it’s a way of life, I’m always recording, I’m always on the road. There are so many things still to do in the future. There is never a shortage of things to keep me busy. But you know I had to fight to get the front cover artwork.”

It’s a striking black and white photograph of Leon Russell. “They want everyone to look real clean and pretty, but I said there is something to be said for truth in advertising.”

And therein lies the secret to Leon Russell’s continued appeal. His songs ring out with an honesty, truth and authenticity so very rare in music today.

—

FREDDIE KING

Getting Ready, Shelter 1971

_Russell teams with the legendary Texas guitarist. _

Tremendous set of raw, passionate blues recorded at the former Chess Studios in Chicago, which, overseen by Russell, captures King at the top of his game with wild soloing, fine boogieing and innovative experimentation.Texas Cannonball (1972) and 73’s churchy Woman Across The River, also recorded with Russell for his Shelter label, are equally great.

RECOMMENDED RUSSELL

Leon’s musical journey in a nutshell…

LEON RUSSELL

**Leon Russell, **Shelter, 1970

Where it all began.

This self-produced debut, issued on Russell’s own label, sits midpoint between country, gospel, soul and blues and introduces Russell as a major singer songwriter talent. A Song For You, Delta Lady and Hummingbird are all stone-cold classics since inducted into the Americana songbook.

LEON RUSSELL

Life Journey, Universal 2014

Latest album shows Russell still has what it takes.

Mammoth 36th solo album and follow up to 2010’s The Union. Produced by Tommy LiPuma, executively produced by Elton John, with guest spots from Robben Ford and the Clayton Hamilton Jazz Orchestra sees Russell reminisce on emotionally committed takes on That Lucky Old Sun, Georgia On My Mind, The Masquerade Is Over et al plus two newies.