From a scene that sprung inconspicuously from the basements and dives of the US, 30 years ago, hardcore music had become a way of life. Ultra-fast, far heavier than punk and drenched in anger and passion, hardcore was desperate music created by the underprivileged and disillusioned kids of the US. These were the kids who refused to let their lives drift down the same paths as the jocks or drug-addled hippies and dropouts at school. For many, this anti-mainstream attitude would later turn from close-knit community spirit into militant violence aimed towards those who dared oppose their way of life. But for the most part, hardcore was about the music, spawning dozens of iconic bands like Black Flag, Minor Threat, Gorilla Biscuits and Dead Kennedys.

Today, not only are the originators like Bad Brains and New York’s Gorilla Biscuits revelling in the longevity of hardcore with reunion tours, but newer bands are ensuring the legacy lasts the millennium. Thanks is in part due to the likes of Biohazard and Dog Eat Dog, who helped bridge the gap between the early days and the new breed of hardcore bands who followed almost 30 years later.

In the early 80s, many New York kids, alienated by mainstream culture and turned off by the pomp of hair metal bands like Mötley Crüe and Ratt, took solace in the welcoming vibe of Sunday hardcore matinees at legendary New York club CBGBs. One such kid was Pete Koller, guitarist for hardcore luminaries Sick Of It All…

“Hardcore matinees at CBGBS were my church. It was there that I learned how to make friends and how to stand up for those friends,” Koller says about the scene that changed his life. “Going to [actual] church I had someone telling me that everything I was doing was bad, that I was going to hell, but that God loves me. I mean, what the fuck is that?”

Hardcore wasn’t just a form of music, it was a way of life for thousands of American kids. This self-sufficient underground movement was far from the bloated world of commercial music, and it was this individuality that was alluring to so many. For the outcasts it was the unified ‘gang’ they so desperately sought, promoting community rather than violence and segregation.

“CBs was a friendly place,” remembers Koller of the now defunct venue. “Even if the bands kinda sucked you’d still go because you got to hang out with your friends. All week you’re going to a high school full of people wearing Capezios [shoes] and driving Iroc Cameros. We didn’t have money for that shit and we wouldn’t be caught dead living like that. CBs was the way to meet up with people. We’d talk about how the week sucked but we’d get down on the dance floor and let out our frustration and everyone would have a good time.”

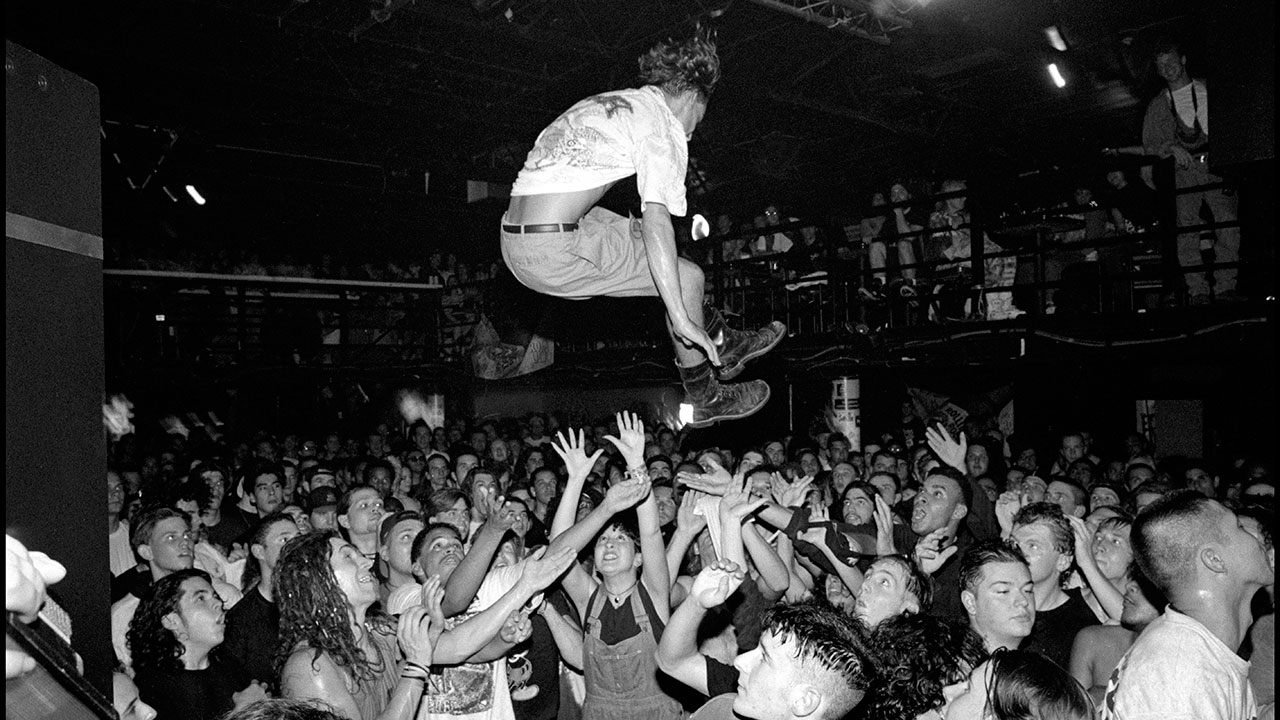

Hardcore music didn’t incite the typically ungraceful melee of bodies you’d find in a metal mosh pit. Hardcore pits were characterised by ‘slamdancing’, which originated in Southern California and involved stalking the pit, swinging your arms and trying to strike as many people as possible. Today, the circle pit and ‘wall of death’ are traditional fare.

“Hardcore was the beginning of my life,” continues Koller. “Before that I was just hangin’ around and wasn’t really into anything. Kids in the hardcore scene were people like us. Nobody cared what you looked like. There was a little bit of danger, but we fitted in there. Everything was about music and it was our entire lives.”

Most of the bands that sprung from the scene were formed by kids at the shows who had anger to vent and points to make. Touring the world with a metal band was out of reach, but playing hardcore was something anyone with the right mind-set could achieve. Koller, who recently celebrated 20 years of his band, was taken with the accessibility of the scene: “I’d watch bands like the Cro-Mags play,” he says. “The opening bands would be playing, then you’d see Cro-Mags singer John Joseph in the pit and two seconds later he’d be onstage. There was no separation. Those guys weren’t stars; the guys in Cro-Mags and Agnostic Front were homeless kids. They were down on their luck but music kept them alive and gave them something to live for. My brother Lou [SOIA vocalist] and I saw this and were like, ‘We can do this shit too!’ I didn’t know how to play guitar, but I got one and learned to play by writing hardcore songs.”

Hardcore’s sound takes characteristics of both punk and metal. The stripped-down style of writing was more punk because the kids weren’t proficient musicians, while the power came from metal bands like Judas Priest. “I couldn’t understand how to play an Iron Maiden song,” remembers Koller of the early days, “so the first song I wrote was Friends Like You, which uses a barre chord that starts on E and makes a box. We play that song to this day and everyone goes crazy. Hardcore is so simple, almost caveman. It’s primal and you’ve gotta let loose.”

Much of the scene followed a DIY lifestyle, putting on their own shows, setting up their own labels and penning their own fanzines. This was mainly through necessity because no-one wanted to associate with the hardcore kids; their music was anti-social and they dressed to intimidate with their typically shaved heads, black army boots, heavy chains and customised T-shirts.

“In the early days, everyone who was involved lived it all,” says Bad Brains’ Dr Know. “All the bands, all the people who came to the shows – it was a close-knit family vibe. We were all kids living in the same houses, scraping money together with nowhere to play and no equipment, so we were using other people’s stuff. Because the music wasn’t popular, there wasn’t any money.”

As with all things that challenge mainstream conformity, hardcore was treated with scepticism and the authorities sought to close down shows that were perceived as rough. Seclusion and discrimination were popular topics for hardcore songs, especially for Bad Brains, a talented, all-black band influenced as much by Bob Marley as they were The Ramones.

“That’s why we wrote the song Banned In DC,” says Dr Know of the classic cut from the Brains’ 1981 debut album. “It wasn’t just us, it was the whole scene. The authorities couldn’t understand the scene; it’s true of all new music. It’s like, ‘Those kids are going crazy, that damn punk music, we gotta stop it, don’t book it’.”

“It was us against them,” adds Koller. “The cool thing about hardcore was that it was starting about the same time as hip-hop. Hip-hop and hardcore were both street music. At that time everyone got along – you would see black kids and Spanish kids at shows. There was such a minority of us. We all gravitated towards each other and we all looked out for each other.”

What started in New York and Washington quickly spread across America with pockets of hardcore forming in Boston, LA and San Francisco. Each of these collectives spawned their own group of monumental bands with slightly different takes on the hardcore sound.

One of the definitive bands from Washington was Minor Threat, fronted by hardcore visionary Ian MacKaye who famously started the ‘Straight Edge’ movement. This involved a voluntary abstinence from alcohol, drugs, promiscuous sex and, in some cases, a commitment to vegetarianism or veganism. Check out the lyrics from the band’s song of the same name: “I’m a person just like you/but I’ve got better things to do/than sit around and fuck my head/hang out with the living dead.” It was a lifestyle that resonated with a lot of kids who bore witness to the ugly rise in drug culture. Straight Edgers would draw Xs on the back of their hands at gigs to symbolise their commitment, and this symbol and attitude can still be found in hardcore scenes across the globe.

Today, the early 80s hardcore ethic still exists in places in Europe and America, as well as in the UK, but the larger picture has been watered down by MTV and the music press, tagging many bands that emerge from the metal or punk scene as hardcore. “Bands like Comeback Kid tour like crazy, they put out great records and don’t bow to any trends,” says Koller, signing off with his take on hardcore in the modern world. “If you give up when you don’t get signed right away or play arenas, then you don’t have the heart. You have to have a passion for it and the heart to deal with tons of bullshit.”

“True hardcore has to have an element of the underground and rebellion,” concludes Dr Know. “The term hardcore [has] migrated to all flavours of music today… the rap world, reggae world. My definition of hardcore is keeping it real, and there’s a lot of people out there still doing it.”

This article originally appeared in issue 173 of Total Guitar Magazine.