In hindsight, there was more shared ground between our beloved prog heroes and the 90s musicians behind techno, ambient, electronica and IDM (Intelligent Dance Music) than first met the ear and eye. And we’re not just talking about their long hair.

It is quite legitimate to make a connection between the 70s prog brigade and the grandiose, expansive structures and textured, trippy atmospheres of The Chemical Brothers, The Orb, Orbital, Moby, Leftfield, Aphex Twin, Underworld, 808 State, The Shamen, Ultramarine and The Future Sound Of London (FSOL). Indeed, ‘progressive dance’ was a term bandied around at one point as a suitable umbrella for these acts; ‘hippie techno’ was another. As features editor at Melody Maker, I remember setting up a summit in 1993 between Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour and Alex Paterson of The Orb, so that they could discuss in depth their similarities of sound and vision, ideology and intent.

Future Sound Of London were Brian Dougans and Garry Cobain, and were steeped in prog and psychedelia: their 1994 album Lifeforms even featured contributions from Robert Fripp, Klaus Schulze of Tangerine Dream, and Ash Ra Tempel. A year earlier, FSOL had transmogrified temporarily into Amorphous Androgynous and released Tales Of Ephidrina, which sampled Peter Gabriel’s Passion: Music For The Last Temptation Of Christ.

By 2002, the duo had moved in a less electronic, more organic direction for The Isness, hailed by some as a latterday neo-prog classic. With songtitles such as Go Tell It To The Trees Egghead, Her Tongue Is Like A Jellyfish and The Galaxial Pharmaceutical, the album invited comparisons with the Moody Blues, Aphrodite’s Child, Donovan and Pink Floyd, while reviewers proclaimed it, variously, “a modern progtronic rock opera” and “the most intelligent, coherent, ‘collage-ist’ summing up of everything that was wonderful about progressive rock and psychedelia that one could wish for.”

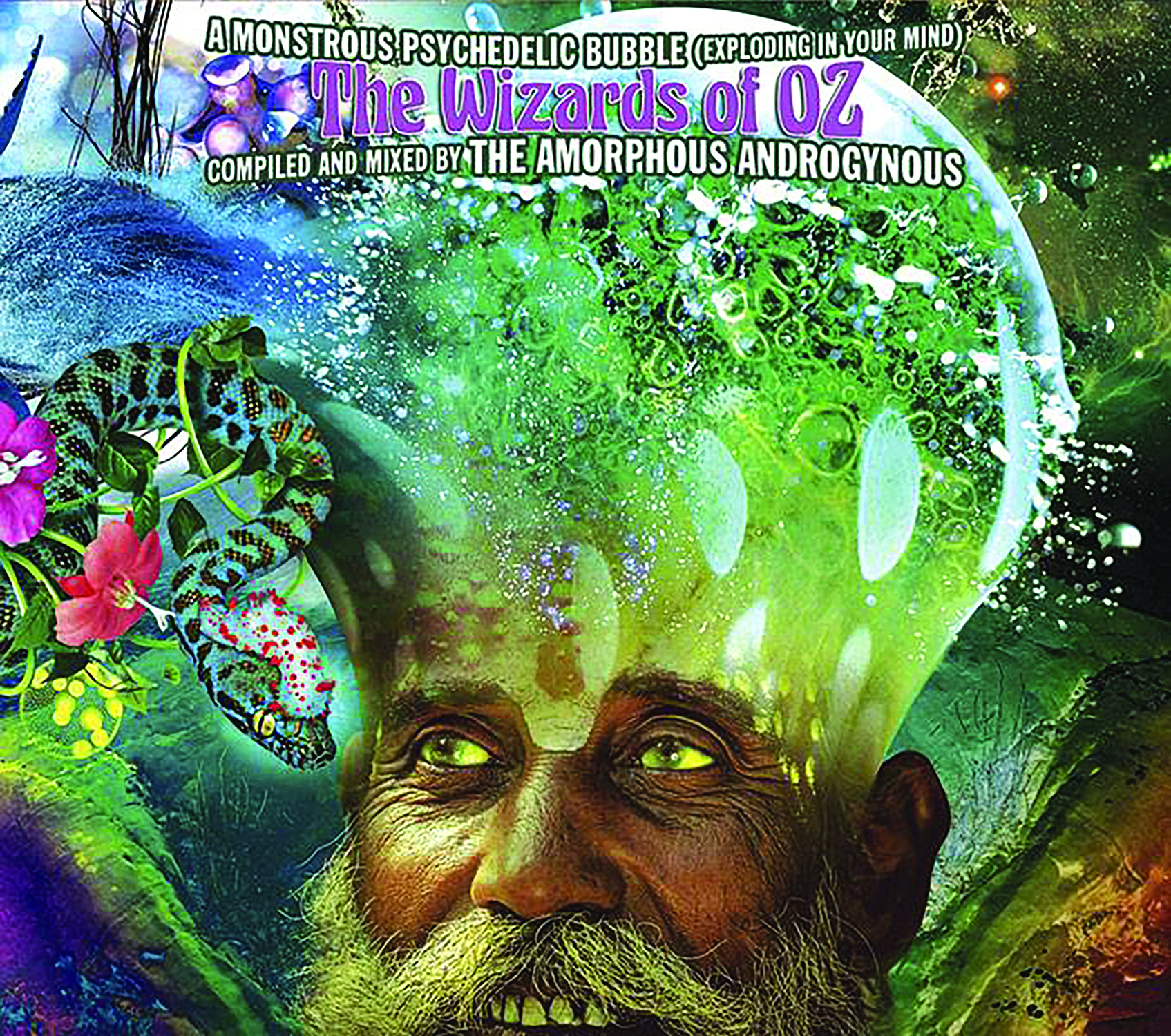

And now, The Amorphous Androgynous have travelled to the furthest reaches of the planet (Australia and New Zealand) to bring us the latest in their series of A Monstrous Psychedelic Bubble Exploding In Your Mind… mix CDs. Their 2008 instalment so impressed Noel Gallagher that he invited AA to collaborate on an album.

The Amorphous Androgynous’ latest prog/psych purée ranges from the Hendrixian thunder of New Zealand guitarist Doug Jerebine to the proto-kraut rock of The Missing Links; is subtitled The Wizards Of Oz and is devoted exclusively to mostly obscure music of the cosmic kind from the Antipodes, from the 1960s to the present, from “Kiwi Krautrock to Aboriginal space jazz to OZ dream pop to cOZmic funkrok”, according to the press release accompanying this 34-track, two-hour CD extravaganza.

When Prog asks Garry Cobain why he needed the The Amorphous Androgynous project moniker, despite it being the same line-up as FSOL, his reply is suitably out-there.

“I wanted to write spiritual, cosmic rock’n’roll operas,” he says.

Cobain explains his evolution, from classic rock-loving teen from Home Counties Bedford into Floyd, Hendrix and The Doors, to acid house casualty based in Manchester, which is where he met Dougans at university in the mid-80s. Their roles were clear enough: Dougans was the studio boffin, Cobain the charismatic frontman, although both knew their way around a computer.

As FSOL, they enjoyed Top 30 hits, notably with 1992’s Papua New Guinea single, ’93’s 40-minute epic Cascade and the 1994 album Lifeforms, before Cobain felt a need to immerse himself in the prog/psych ocean, via Amorphous Androgynous.

There had been rumours explaining this transformation, one of which was mental illness. In reality, it was his physical health that was poor. Unbeknown to him, Cobain had been slowly poisoning his body with the mercury from fillings in his teeth.

“I’d been ill, as a result [of the mercury], for most of my life,” he reveals. “I’d had all sorts of immune disorders, a heart that didn’t work properly. I’d never felt right, but I just accepted it. In 1997, I decided to find out what was underpinning my illness. I looked at everything, including emotional issues.”

Eventually, Cobain found a cure for his illness in a combination of “food, mysticism, and yoga”, mainly in India, where he learned about Ayurvedic medicine and “acquired the tools to self-cure”.

The Amorphous Androgynous were born out of this period of spiritual awakening, when Cobain was “finding healers and mystics and people of all persuasions”, including a blind sitar player from Stoke Newington with whom he’d attend Indian weddings. Meanwhile, he would travel the world, “to heal and find out loads of stuff”. He was, he says, “plugging into the truth”.

The Isness was the first manifestation of the new, healthier Cobain. Although it had the sound of someone on drugs, he wasn’t partaking.

“Funnily enough,” Cobain says, sounding every inch the flower child out of time, “I realised early on that everybody is absolutely fucked up on drugs because of air and water. Nobody and nothing’s natural. There are heavy metals in vaccinations, the air is full of benzine, our water is full of fluoride… As for our food, there are 30 chemicals in strawberries. My quest was to try to be as pure as I could.”

This he achieved via meditation, yoga and “fasting enemas”.

“I’d walk into the studio every day and Brian would go, ‘Fuck! This is a lot more interesting than going out and taking drugs and drink, pretending to be rock’n’roll.’ Potentially this was the new rock’n’roll – becoming as pure as possible to find some clarity. The clearer I was, the more expressive I became. And the more people thought I was on drugs…

“I realised I’d never be free,” he continues. “Getting ill was expressive of me as a human. I wasn’t alive. I wasn’t happy generally. Society, elders, school, parents…”

Cobain was on a mission to get happy. At the same time he realised his musical future lay, not in electronic soundscapes but actual songs – albeit experimental, exploratory ones – with words. Loquacious in interviews and with ideas to burn, Cobain was as far from the anonymous, monosyllabic techno muso as you could get.

“The truth is,” he says, “on press days I’d speak to hundreds of journalists from around the world. I was doing half-hour speeches.”

Cobain scoured second-hand shops for “obscure prog” and as many records as he could find bearing “interesting instrumentation and cosmic songtitles”. Donovan, the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Alice Coltrane were among the artists he discovered. These would form the basis of the Monstrous Psychedelic Bubble mix CDs.

Had the 47-year-old been around in the early 70s as a record-buyer (he was born in May 1967, two weeks before the release of Sgt Pepper), Prog wonders whether he would have been more into psych, prog or kraut?

“Probably I’d have been dabbling with them all, and been the first to put them all on one album,” he suggests. “People are surprised to see John Lydon was into Kate Bush. I’m not. A hippie is a punk in a different era.”

The Amorphous Androgynous of The Isness and its follow-ups Alice In Ultraland (2005) and The Peppermint Tree & The Seeds Of Superconsciousness (2008) reflected Cobain’s intention to “use the studio creatively, only with instruments not alien electronic noise”. These albums were a blend of strummed guitar and what he calls “studio bend”. Having grown bored, after a decade of making electronic dance, with beats, he discovered 1967. Once he’d ransacked psychedelia, he moved onto 1972: prog’s golden age.

“By Alice…, we’d started to get a lot more prog,” he admits. Since then, there has been a series of soundtrack albums showcasing successful attempts, using live musicians, to recreate, for example, blaxploitation-era scores, and the Monstrous Psychedelic Bubble… series, of which The Wizards Of Oz is the latest and, arguably, greatest.

“We began to hatch a plan for an album devoted to Antipodean music in 2004, when we were on tour in Australia,” explains Cobain. “But it’s not your average psych album. We’re not interested in the past. We want a modern revolution; it’s just that we need the wisdom of the past to do that.

“I like our disrespect for history,” he adds. “I’m a non-expert.”

His is a punk vision of psych and prog. “There’s a rebelliousness to what we do,” he decides. It chimes with the times, and taps into insurrectionist currents. “I can see psychedelic bands around the world, and I see people disenfranchised with governments, yearning for freedom. And that’s what Monstrous Psychedelic Bubble is about – a birthright for freedom, colour and interconnectedness. That is the future. A vision that is progressive.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 56 of Prog Magazine.