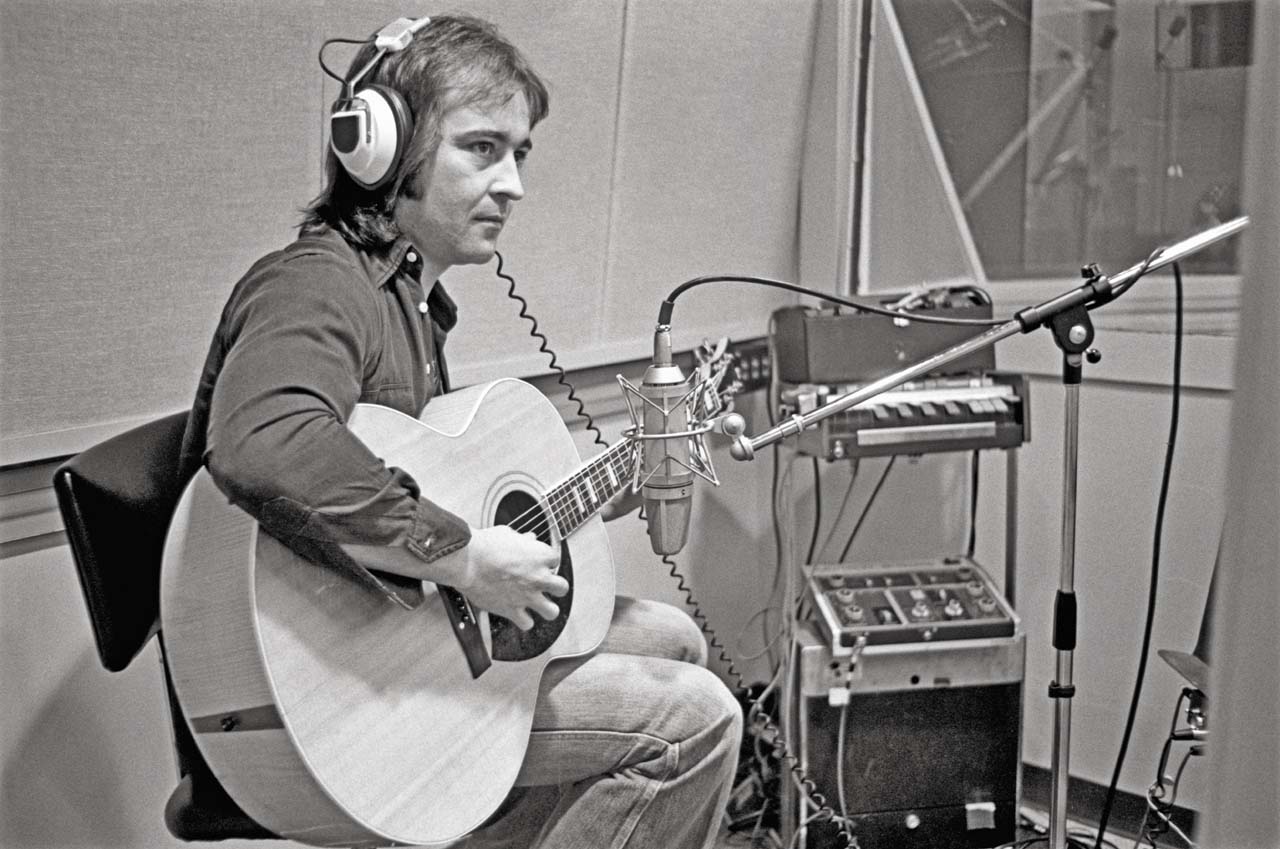

By 1973, Mick Jones already lived a colourful, peripatetic musical life. Born into a middle-class household in Reading in 1944, he had grown up a music nut and was self-taught on the guitar. At the age of 18 he went off to tour France as a member of the backing band of one Dick Rivers, a typically French approximation of Elvis Presley. That gig came to an abrupt end for Jones when he made off with Rivers’s fiancée, going to live with her in Paris.

He spent the next eight years in France, working as a bandleader and arranger, first for a Bardot-esque chanteuse, Sylvie Vartan, and then her husband, Johnny Hallyday, a national icon. With Hallyday, Jones got to travel the world and live the high life. He cavorted with The Beatles in Paris, and encouraged such visiting British musicians as Jimmy Page, Peter Frampton and Steve Marriott into doing sessions with Hallyday. Tiring of constantly being at Hallyday’s beck and call, and wanting a new challenge, he returned to England in 1971, and soon after joined a reactivated version of psychedelic rockers Spooky Tooth.

By 1974 we found in Spooky that we were getting a better reception in the States than back home in Britain, so made a collective decision to relocate to New York.

Going off to live in the Big Apple certainly appealed to me, and I took an apartment on 34th Street on the West Side of Manhattan and right next to the Lincoln Tunnel. I was sharing the place with a pal of Gary’s [Wright, keyboard player/vocalist]. Unfortunately, this so-called friend ended up making off with the money I was paying him in rent rather than handing it over to the landlord, and so we both got evicted. New York’s a ruthless city. Someone came one morning and stripped the place of everything that was ours. All I was able to salvage was an armful of clothes and a couple of guitars.

Being made temporarily homeless was soon enough the least of my worries. The band had just cut a new album, The Mirror, with Eddie Kramer. Eddie was fresh from engineering Led Zeppelin’s Houses Of The Holy and captured our band on a roll – only for Gary to stiff the rest of us. Before the album could be released, and out of the blue, he upped and quit Spooky to go back to his solo career. I was left high and dry in New York, and without a clue as to what my next move was going to be. I seriously considered returning to England and starting over a whole new career, such as going to medical school or becoming a dentist. The second option was the most attractive to me, because it took less time to qualify and paid good money.

I was rescued from looking into people’s mouths for a living by the offer of a job from Spooky’s manager, Nigel Thomas. Nigel had set up a record label, Goodear Records, and wanted me to run it for him. He made me president of Goodear, and that also gave me the opportunity to get back into producing. We worked out of the famous old Brill Building, and Nigel even threw me a swanky apartment into the bargain. The drawback was that Nigel was also something of a bounder. He comported himself like an English gentleman, but in reality ripped people off left, right and centre, and including his artists.

In short time I found myself getting into all sorts of tight spots with Nigel. He sent me off around the world to collect money from the various deals that he had done with publishing companies, and all which got shafted in the end. At one point he determined to buy Stax Records, hook, line and sinker. In order to secure a loan for the deal, he arranged for us to have a dinner with the president of the Union Planters Bank in Memphis. When we had finished our meal, Nigel handed over his credit card to pay the bill. Of course, it bounced, and the maitre d’ cut it up right there in front of the very guy that Nigel was trying to tap for millions of dollars.

Eventually I grew uncomfortable with being on the other side of the desk, and not just because of Nigel’s shenanigans; I simply wasn’t cut out to be a corporate executive.

Serendipitously, another band gig pretty much fell into my lap. Through working at Goodear, I had been introduced to Bud Prager, who was then managing the former Mountain guitarist, Leslie West. Mountain had not long broken up, and Leslie was on the lookout for a second guitar player for his new solo band. Bud arranged for me to audition. Leslie loved the way that I played, so the job was mine.

The band was a power trio and also featured Mountain’s ex-drummer, Corky Laing. Together the three of us wrote a bunch of songs and cut an album as the Leslie West Band. It was a good record, and we managed to play a handful of excellent shows, but things quickly deteriorated. At that point in time Leslie had a well-documented problem with heroin and it caused the band to break up. He did go into rehab, and we would hear back that he was doing great and testing clean, whereas in reality he had done a deal with a fellow patient to swap each other’s urine samples every morning. One of the last shows that we did was in New York. Towards the end of our set, Leslie walked off stage and vanished from the venue. It turned out that he had taken his guitar down to a place on 48th Street and pawned it to buy drugs.

On the spot, I quit. I had, though, seen enough to know that Bud was a bright guy, so told him I was going to form my own band and asked him to be my manager. He had to borrow a hundred thousand dollars from a trust fund of his wife’s to finance the deal, which I don’t believe she knew a thing about until years afterwards. From that moment on, Bud and I formed a close bond. His business partner, Gary Kirfirst, also happened to be managing another of Leslie’s former Mountain bandmates, bassist Felix Papallardi. Felix had established a small recording studio in their offices and I was able to use that as a writing room at first, and later for auditions and rehearsals. That place was a lifesaver for me, because I had to scrape to get by.

I felt as if I had been released. Quickly, I wrote four songs, one of which was Feels Like The First Time. I had also started to hang around with a guy named Ian Lloyd. It was only once we had gotten to know each other that I found out that Ian had been the original frontman with a New York band, The Stories. Three years earlier, they had scored a number-one hit in America with a cover of the Hot Chocolate song Brother Louie. That single had become a millstone around Ian’s neck. In reality he was a fan of harder, more progressive English rock bands, such as Genesis, but had got stuck on what they called the chitlin circuit, playing pokey soul joints.

Ian was altogether great to me. Not only did he sing guide vocals on my new songs, he also put me in touch with some of his contacts. I had already come across a keyboard player, Al Greenwood, when Ian turned me on to a fellow Englishman, Ian McDonald. This Ian had played keyboards and flute in King Crimson and was doing session work in New York. King Crimson was a big deal at the time, so I had an immediate regard for Ian’s playing and asked him to come by my adopted studio for a jam. All along I had envisaged there being a multi-instrumentalist in my band, and Ian was perfect for that role. He was the type of intuitive musician that could add different textures and colours to any kind of song.

Almost as soon as I had recruited Ian, I also encountered Dennis Elliott. I had gone off to upstate New York to do a session with Ian Hunter, and Dennis was his drummer. Once again I was instantly impressed, and spent the next couple of months trying to subtly prise Dennis away from Ian’s band. He eventually succumbed, and went on to become an integral part of our band’s sound.

Dennis isn’t a flashy player, if anything he’s slightly understated, but he has an acute sense of feel and real power. Right from the start, Dennis and I locked in so well together that we didn’t need to hear a bass part. That was perhaps why bassist Ed Gagliardi was the last musician that I brought into the fold. By then I had a name for this band of mine too, which was Trigger, but no lead singer.

I had auditioned at least forty candidates for that defining role, but without success. It had got to the stage where I was considering offering the post to Ian Lloyd. That was a very close-run thing, but Ian’s voice just wasn’t quite right for the overall sound that I had in my head.

- Mick Jones' 11 Favourite Foreigner Songs

- The TeamRock+ Singles Club

- TeamRock Radio is back. But after what happened, why have we kept the name?

- Foreigner - 40 album review

I had actually met Lou Gramm when I had toured America with Spooky Tooth. The guy who did our promotion work on the East Coast lived upstate in Rochester, and in his spare time managed Lou’s then band, Black Sheep. He brought Lou along to one of our shows, and Lou and I chatted backstage that night. But he was playing drums at the time, and told me that he figured that was going to be his ultimate destiny.

After six more fruitless months without being able to find a singer I was almost tearing my hair out in frustration. One afternoon, I was up at the studio finishing off the backing track for the Feels Like The First Time demo. On the mixing desk, I had stacked a pile of records that I’d been sent. For a break and just to take my mind off the task at hand, I pulled out the Black Sheep album that my old friend from Rochester had mailed me. Within ten seconds of it hitting the turntable, I knew that I had found the voice.

The next thing I had to do was track Lou down in Rochester. I discovered that he was working on a building site and managed to get a number for him. When I called, he was carrying a load of bricks up a ladder. He came down to talk to me. He told me that he had got fed up of singing and was concentrating instead on the drums. I was gobsmacked, because he had such a fantastic voice which I knew could potentially put him right up there in the pantheon of classic rock singers. We chatted, and eventually I was able to persuade him down to New York for a few days. The song Long Way Home on our debut album [Foreigner, 1977] was subsequently written about that conversation and what came to pass. As Lou sang in the first line, I did indeed phone him on a Monday.

The first day that Lou joined us in the studio we ran through a couple of songs with him, and I felt as if I had been hit by a bolt of lightning. Right away I knew that this could be the start of something special. Lou had a feel for soul music, which was a great credential in my book, and then again this indefinable magic. He hadn’t, though, ever worked with anybody that could help him to shape his voice – and with such things as phrasing, the key, and on melodies – and which I would be able to do.

With Lou on board we completed our demo tape and sent it to Jerry Moss at A&M. Jerry was one of the great record men of that era. Together with his partner Herb Albert, he had signed Humble Pie, Free, Procul Harum and Joe Cocker, and so A&M would have been a good home for us. I didn’t find out until much later that Jerry had left to go on holiday the very morning that our tape arrived. That was always a big regret of mine. We had also sent it to Atlantic Records, but the head of A&R returned it to us without even taking it out of the box.

Bud had connections at Atlantic. He began making inroads towards at least getting us listened to, and then John Kalodner arrived on the scene. John would go on to sign both Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins to the label, and also to great success at Geffen and Columbia, but just then he was the new kid on the block. He had been working as a rock writer, so when he happened upon our tape and saw the line-up of the band, he was familiar with Ian and me, and to a certain extent Dennis. He thought it was fantastic, and from that moment on caused pandemonium at the label, pestering, yelling and screaming at people to listen to us. Finally our tape made its way up to Atlantic’s president, Jerry Greenberg. A few weeks after that, John brought Jerry down to our studio, and within days we had been signed to Atlantic.

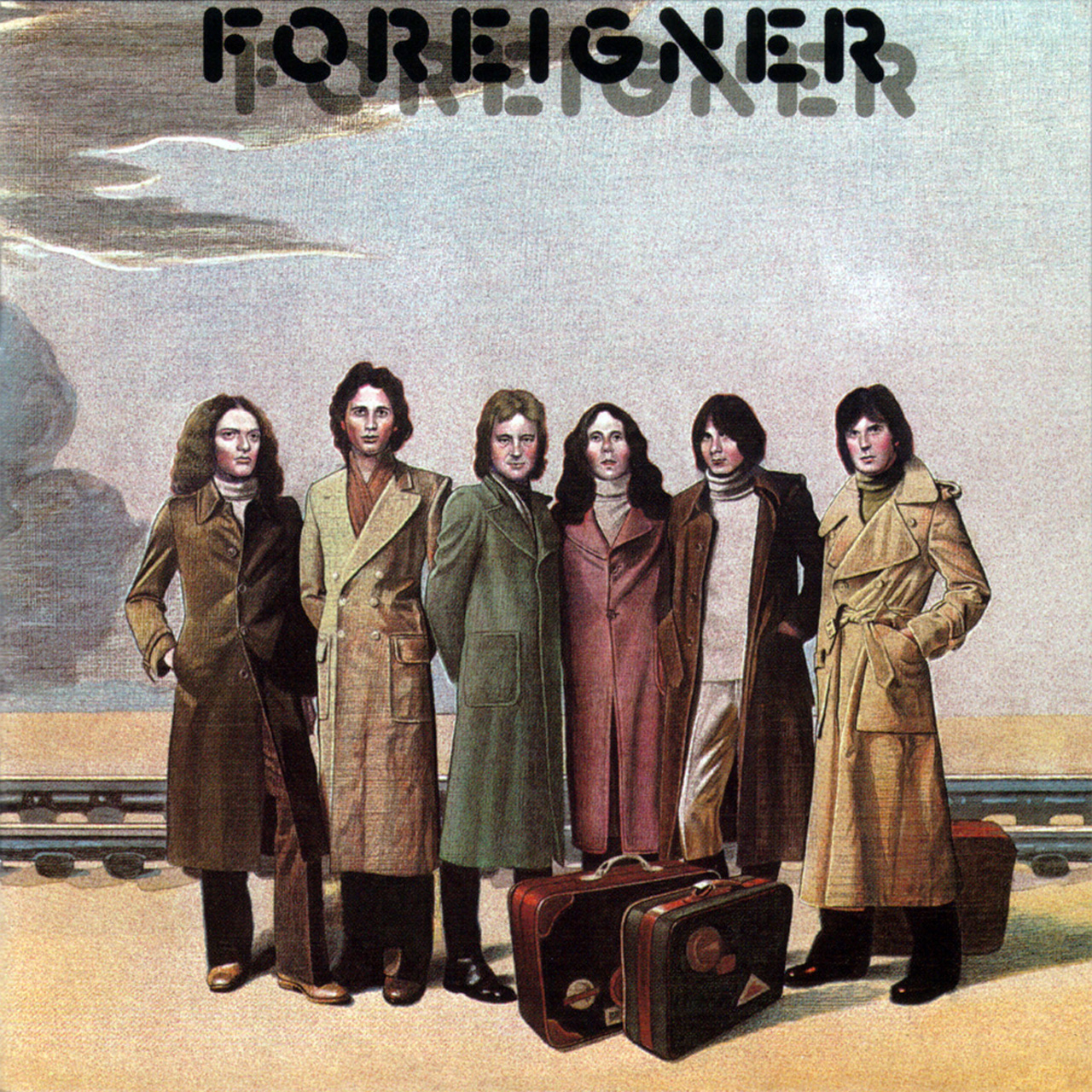

Not unwisely, it was also John that suggested we bin the name Trigger. I instead came up with Foreigner, to reflect the make-up of the group: three Brits and three Americans. Since we had three rookies in the ranks, I also felt I had to lead the way in all other respects, and very much took over the reins.

In fact it was during that period that I first became aware of precisely how much of a control freak I am. One of the first decisions I took unilaterally was that I wanted to have Roy Thomas Baker work with us on our first album. Roy had made his name producing Queen, but ironically was booked up on an Ian Hunter record, Overnight Angels. He was, though, good enough to recommend to me Gary Lyons, who had engineered for him all of the Queen stuff. In turn, Gary wanted to bring another guy over with him from England, John Sinclair.

The pair of them flew to New York to meet with me, and we all seemed to be on the same page. I was particularly interested in us getting an instantly recognisable vocal sound and of certain songs having background vocal choruses. Even though neither of Gary or John had produced a record before, Gary at least clearly knew what he was talking about, and so I rolled the dice and gave them a go. We recorded at Atlantic Studios in New York, and then Gary and John took the tapes back with them to London to do the mix. I still hadn’t got a Green Card, so Ian accompanied them on the band’s behalf.

When Gary subsequently had a couple of the mixes FedExed over to me, they were miles from the vision that I had for Foreigner. I immediately had all of the tapes returned to me in New York. Ian flew back to join me and together with a staff engineer from Atlantic, Jimmy Douglas, we raced to remix the album in a very short amount of time. Even still, we ran a month over our deadline and racked up costs. That would become the norm for us, but I was always determined that our records be representative of the band.

The night that I was finally able to take the completed master home with me, I had a little smoke, put it on loud and lay out on the floor to listen to it, staring up at the ceiling. That was one of the most glorious moments of my life.

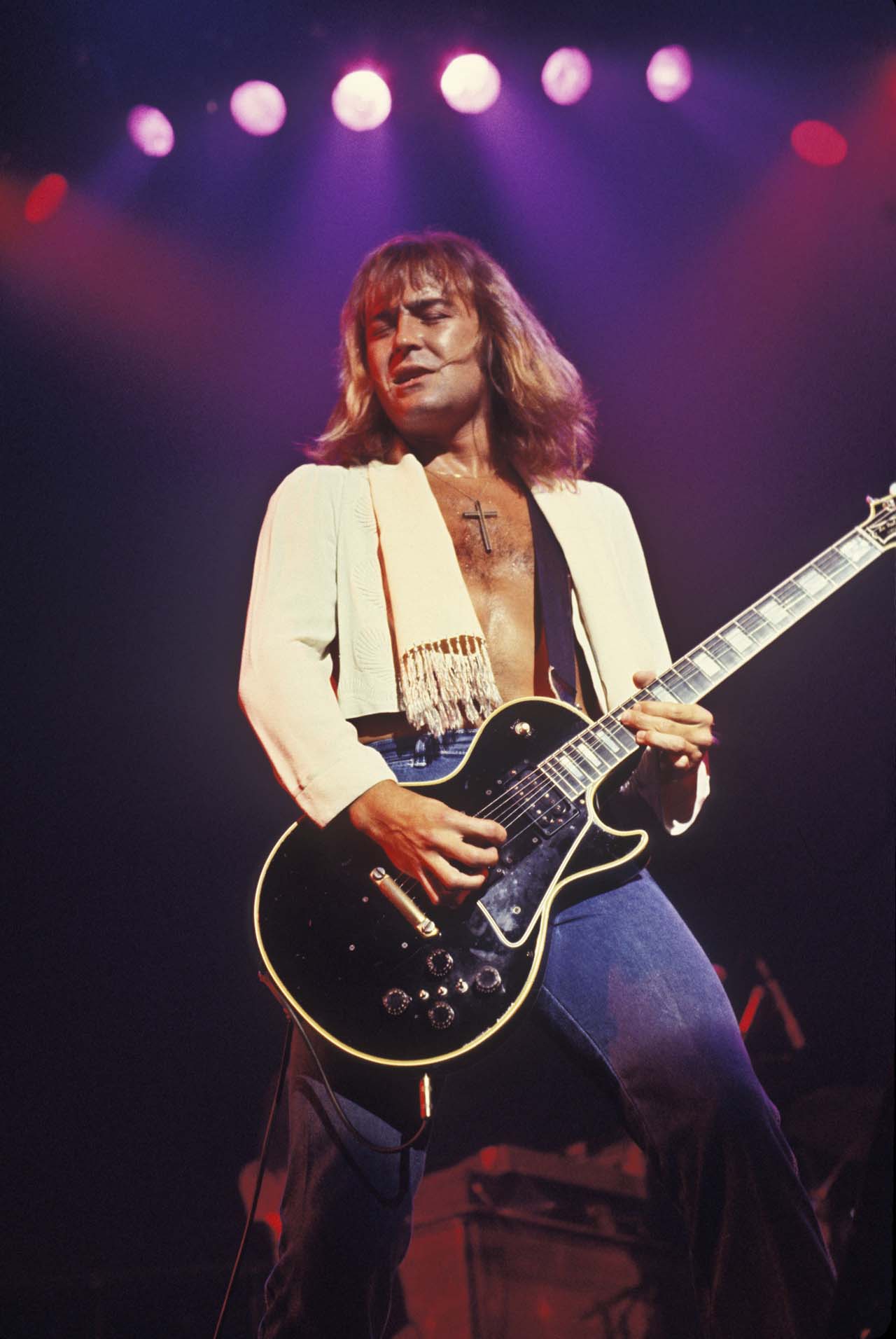

Instinctively, I knew that the record was good enough to allow us to start to make a name for ourselves. But no one in their right mind could have predicted what it would go on to become. Just as soon as it came out, we were being told that it was selling up to three hundred thousand copies a week, and then four hundred thousand. You have to remember that this was 1977; disco was the big thing in America, and punk rock was dawning, so it seemed even more unlikely that a band such as Foreigner would be able to break through.

The scale of our success was pretty much unprecedented. The only new band to have achieved anything like it was Boston, whose debut album had been a multi-platinum phenomenon the previous year. Almost no one else up to that point, including the Stones and Zeppelin, had shifted a million records straight off. The Foreigner album passed that mark in a mere few weeks. It had to be down to the strength of the songs, because we didn’t have an image or gimmick. We raced on to two, three, four and then five million sales. The only two bands that were up there with us all of that year were the Eagles with Hotel California and Fleetwood Mac with Rumours.

My mind is full of snapshots of that time, since the whole was like a blur to me. Early on we did a bunch of shows opening up for Uriah Heep and with Ted Nugent also on the bill. Then a string of dates as support to the Doobie Brothers that helped to bring us to the attentions of a wider audience.

When the album truly took off, we started to do headline shows of our own. That was a testing experience, especially as quite often we found that AC/DC had been booked as our opening act. They had also just signed to Atlantic, and there was a faction at the label that was determined to have them break America. Having to follow them separated the men from the boys. It was the same story with Cheap Trick, who opened for us on our first arena tour of the States. They would go out every night being utterly determined to blow us off the stage, but we held our own, I think.

The whole experience was massively enjoyable, of course it was, but also hard for me to comprehend. Nothing can prepare anyone for being caught up in that kind of whirlwind. At the outset, at least, it didn’t change things too much within the band. A couple of the guys made down-payments on flash cars. In general, though, what we felt most of all was an overwhelming sense of pride at what we had accomplished.

Extracted from A Foreigner’s Tale by Mick Jones. Two editions of the book are available now from www.foreignerbook.com. Classic Rock readers can receive a 15% discount on the price of either edition by using the code ForCR17 at checkout.

The Top 10 Most Underrated Foreigner Songs

The Story Behind The Song: I Want To Know What Love Is by Foreigner