Bucharest, Romania. It’s August 1968 and British popster Helen Shapiro and fellow crooner Tony Bolton are in town with their UK backing group to play a series of concerts. With the Soviet Union glowering disapprovingly on its satellite states opening up to the West, the singing stars and their beat combo are unlikely cultural ambassadors in Eastern Europe. Pathé News, covering this significant event in the life of a Communist country, has a newsreel showing the principals posing for press photos, walking in the park and all the usual grinning and gurning required of obliging pop stars. Then the action cuts to a performance in a concert hall. The brief footage reveals John Wetton, then still a teenager, comping away behind Helen Shapiro’s blue-eyed soul singing and later, adding high-end harmonies to Tony Bolton’s full-throated cabaret-singer rendition of Tom Jones’ Delilah. A few days after that footage had been taken, Wetton recalls they performed in a football stadium filled with pop music-starved young people. Before Helen Shapiro came out on stage, the band covered The Beatles’ Lady Madonna, which had only recently been released, and of course, only in the West. “About 60,000 people in Bucharest just went mental. Absolutely fucking mental. I realised at that moment what you could do with music, about the power of music. It was just incredible. It taught me a huge lesson.”

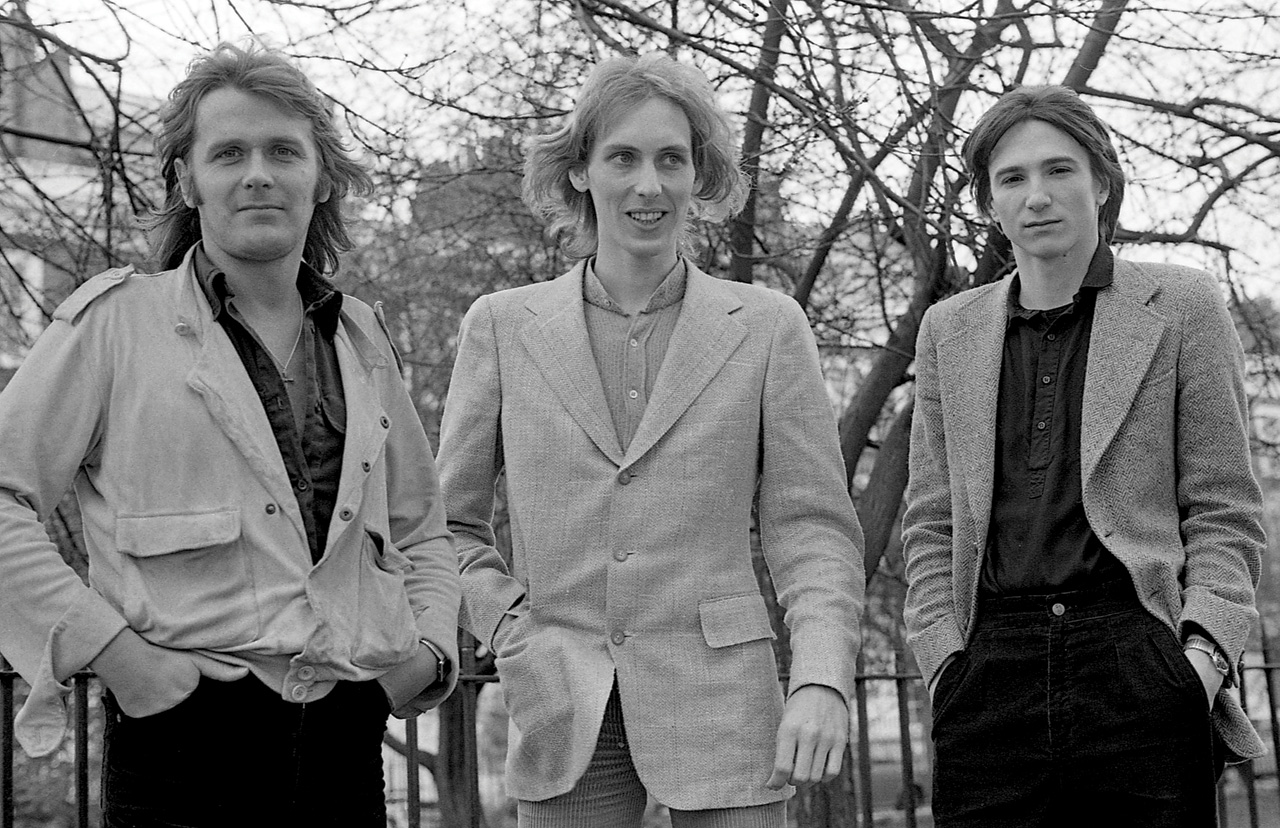

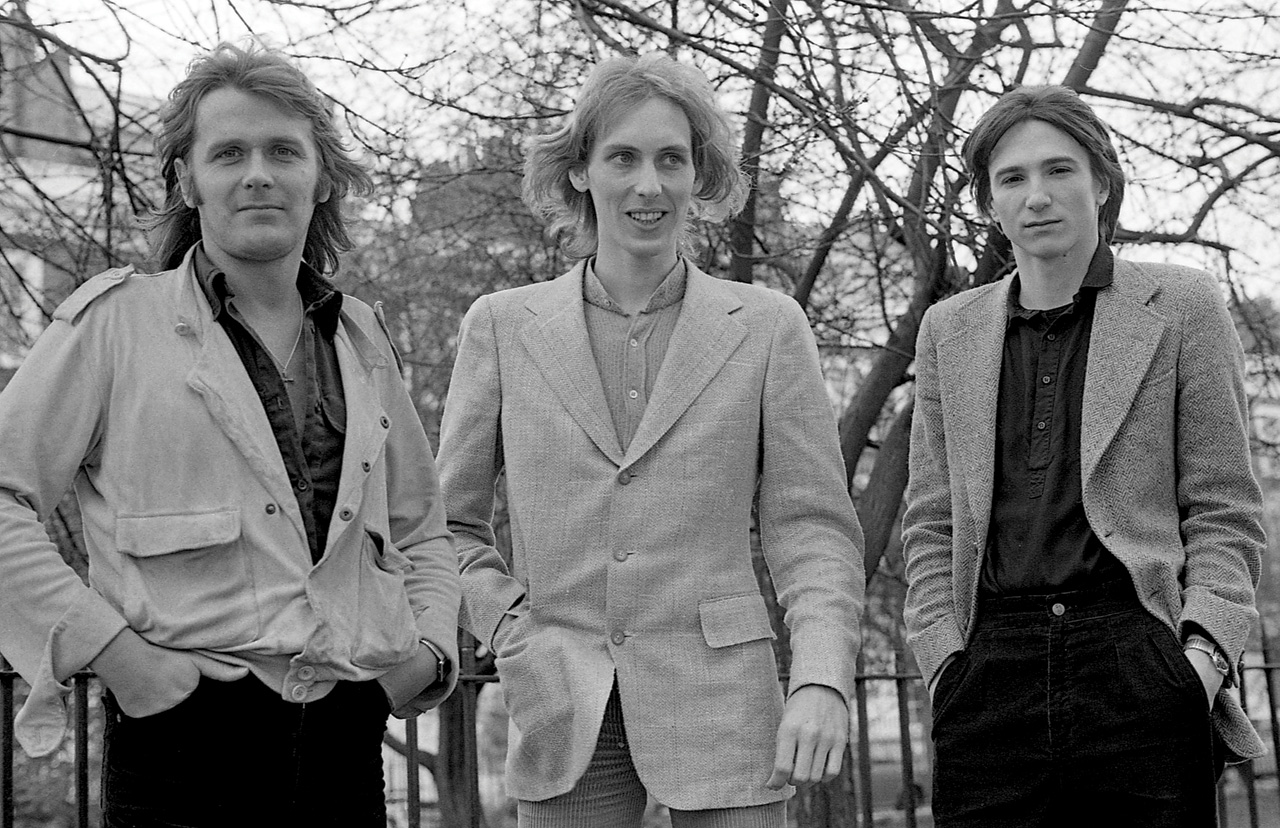

John’s love of music came from a number of directions. Influenced by his older brother playing organ in church and a love of classical music that only intensified the older he got, in common with many of his generation he received the usual American rock’n’roll epiphanies that rolled into town, relieved by something that had more grit and bite to the bland homegrown version typified by Cliff Richard. Richard Palmer-James, who is a couple of years older than Wetton, and who would go on to join Supertramp and write lyrics for King Crimson during John’s tenure, recalls that there was always something special about the kid who relocated with his family from Derby to Bournemouth.

“As soon as he turned up at Bournemouth School For Boys he immediately became known as a musical phenomenon. I can’t remember exactly why, but there was a buzz about him being very musical. He was unbelievably dextrous. We’d never seen a bass player like that. Then it turned out he could play piano and guitar, sing harmonies and he was only 13 or 14. He was the youngest in the band.”

It’s amazing to think that only a couple of months before that, Wetton had been kicking his heels in Bournemouth. He was desperate for a career in music, something actively discouraged by his parents. Expelled from school while studying for his A-levels, Wetton had been attending Bournemouth Technical College, where he continued to neglect his studies in favour of playing bass in local bands. “The day that term ended in June 1968, I came back from college and I walked through my parents’ front door as the phone rang. It was a guy asking me if I wanted to go Romania for six weeks to play with Helen Shapiro. I bit his arm off!”

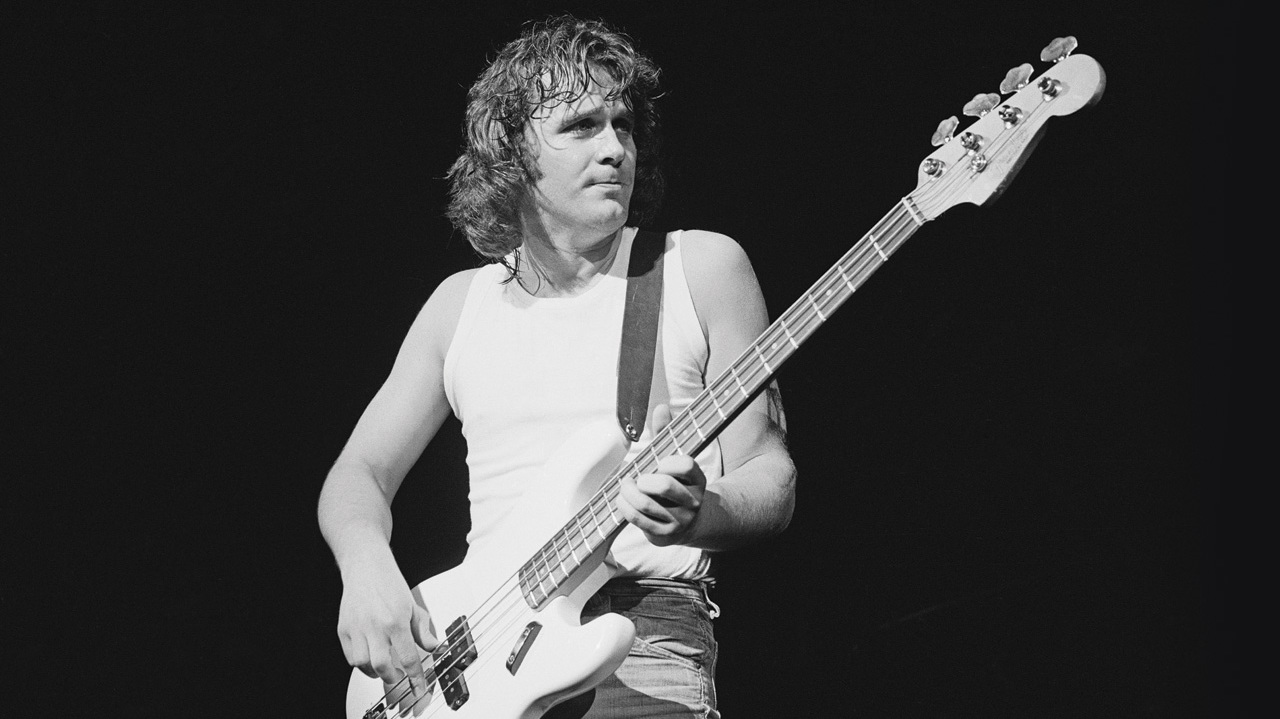

Wetton’s six weeks out on tour with Helen Shapiro gave him enough money to buy his beloved Fender bass, and though his parents were unhappy at his proposed choice of career, there was no holding him back. George Martin took the young bassist under his wing around 1970, with Wetton becoming part of the fittings and fixtures at AIR studios working on TV commercials, backing sessions and anything else The Beatles’ producer threw his way. “George Martin was very good to me. It was a bit like having the Duke of Edinburgh for an uncle,” Wetton laughed.

How did a young lad from Bournemouth get so far so quickly? Obviously he was a good player, but there’s more to it than that. That he got on so well in the fiercely competitive London music scene also came down to the fact that people liked him. Wetton’s broad smile and sharp humour was very much another string to his bow. A room would light up when he entered it. People enjoyed his company, something Wetton innately understood. With a combination of warmth, confidence and an eye for a good schmooze and hustle, there was no way John Wetton wasn’t going to be a success in whatever he turned his talents towards.

His time in King Crimson from 1972 to 1974 saw Wetton go from sideman to frontman when, after a couple of years, he stepped out from behind the Roger Chapman/Charlie Whitney songwriting partnership that dominated Family. His growth as a singer in this time was indisputable, and in the looser, more exploratory Crimson environment his considerable instrumental prowess was given free rein during the band’s remarkable improvisations. Mercurial and dynamic, that these were often mistaken by audiences for through-composed pieces at the time was due in no small measure to the empathetic synergy between the band and, in particular, the melodic and harmonic direction roaring and crunching from the bass. Name any world-class bass player from jazz, folk, funk fusion or rock during this time and John Wetton was every bit their equal – and, in some cases, quite a bit more. After percussionist Jamie Muir left in early 1973, with the sedentary Fripp lodged behind a guitar and Mellotron over on stage right, John became a focus for attention. The self-assurance he exuded on stage grew exponentially in relation to his onstage volume, sometimes to the chagrin of his frustrated and slightly shell-shocked bandmates. Not for nothing did Robert Fripp memorably describe the experience of playing with the combined forces of Wetton and Bruford as being akin to “a flying brick wall”.

Rolling with the blow of King Crimson’s implosion after the release of Red, Wetton’s favourite album with the group, Wetton surfaced in Roxy Music, tailoring his considerable presence on bass to add an extra muscle to the group. He also needed to work to pay the bills. That pragmatism would inform other choices. His stint in Uriah Heep netted him a property, and while the formation of UK with Eddie Jobson, Bill Bruford and Allan Holdsworth initially stemmed from a sense of there being unfinished King Crimson business, there was also an attempt to get things moving in a more chart-friendly direction. Looking back on this peripatetic period, John never quite escaped the feeling he should have been more disciplined. “The right thing to do for me in 1974 would’ve been to move to America. That’s exactly what I should have done. I should never have done that fiddling around that I did from 1974 and 1980. The difference in living in America is you walk into someone’s office and it’s a ‘yes’ before it’s a ‘no’. In the UK, it’s a ‘no’ before it’s a ‘yes’, unfortunately.” America not only gave John and, more specifically, Asia, an emphatic ‘yes’, it provided him with the large-scale canvas he’d yearned for. Prior to Asia the perception was that he was a bassist who indecently wrote songs. John saw himself more as a songwriter who happened to sing and play bass. Asia gave Wetton the writer unfettered access to an AOR landscape ripe for exploitation.

Success of any kind is not without consequences. For every benefit it might confer something else is eroded or lost. Egos are stroked to the point of frenzy, judgement is prone to distortion and success comes with a price tag attached. In the 1980s, where the consumption of Colombia’s most prolific export was routinely costed under the record company’s ‘fruit and flowers’ budget, to then be recharged back to the band bringing in the money. Nor were fame and acclaim any guarantee of peace of mind. Writing in The Conquest Of Happiness, Bertrand Russell observed that “Drunkenness is temporary suicide: the happiness that it brings is merely negative, a momentary cessation of unhappiness.” The root of John’s unhappiness may never be known but over a period of time, his slide into alcoholism dragged him down into the depths of a dark place indeed.

I witnessed John in the grip of the illness in 2000, after being invited to Bournemouth to scour his personal archive for King Crimson-related material. Though we’d often spoken at length on the telephone on numerous occasions when it obvious that John was drinking, I had no idea how ill he was. Arriving a little after 10am, John offered me a can of lager, already a few tins ahead of me. After a couple of hours I made my excuses and left. The months and years ahead were very difficult times for John, who went on to experience a variety of personal and professional setbacks. This is mentioned not to be sensational but to convey the extent of John’s spirit, character and determination that he was able to achieve sobriety and come back from the brink.

If Wetton had learned a lesson about the power of music as a kid playing to crowds in Bucharest, he also understood music as a source of redemption. His recovery from alcoholism was aided by the urge to go back to doing what he used to do so well. The love and support of a good woman, his soulmate and now widow Lisa, meant his later years were productive and filled with a giddy happiness. This despite requiring emergency heart surgery in 2007, about which he penned An Extraordinary Life from Asia’s aptly named Phoenix: ‘All of the good times, and all of the bad/Responsibility is totally mine I know/I rightly stand accused/But I believe that I can change/Yes I can change my world.’ He faced his final illness with an indomitable courage.

Lyricist Richard Palmer-James had a special appreciation for what he regarded as John’s ability to bring out the best in a song through his vocal performance that could enhance an extra dimension which John would inject. “In John’s whole body of work there are a few moments that implicitly open the floodgates and you hear very deep, emotional things coming through. He doesn’t sing it emotionally but somehow in the background, if you want to hear it, then he’s talking directly to you about his own disappointment or pain or whatever. I’m thinking specifically of Who Will Light A Candle? from 2003’s Rock Of Faith album. There’s an emotional outpouring that I didn’t intend in the lyric, but he grabbed it and took it far beyond anything I would have dared to. There’s a little bit of that in King Crimson’s Starless, and I think that’s part of the impact of the track.”

Tony Levin knows from first-hand experience about the effect of the track and what John brought to it on the bass. When King Crimson returned to live work in 2014, Fripp decreed that the group would play Starless, the first time it had been part of a band setlist since 1974. Levin was of course familiar with it.

“We’re talking about visiting the most classic of the most classic great prog bass parts,” he says emphatically. “I’d only played that piece once before King Crimson, and that was when Eddie Jobson was doing UKZ and John guested on a short tour in Poland in the early 2000s. What I learned then about John is there’s a very particular sound that he has on those old things, and it’s most obvious on that section because he starts playing quietly with a nice sound and then very gradually it becomes more growly… I always thought he was using some amazing pedal or a particular bass he had. That’s not true at all. I learned when I played live with him that he sounded exactly the same playing a different bass and playing with a pic gaffer-taped to his finger instead of playing with his fingers. It doesn’t matter.

“That sound actually comes from John Wetton, and to me that’s extraordinary.”

An extraordinary life indeed.

12 Of The Best from John Wetton