You could make a valid argument that the 60s were all about trying to change the world, while the 70s were centred around the individual. Perhaps Jim Morrison summed it up best while performing with The Doors at the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970: “We want the world… and we want it now!”

“A huge crowd – potentially dangerous,” filmmaker Murray Lerner recalls of the event. “A lot of hassle between the songs, but when the songs came, things quietened down. And some great classic rock performances, like The Who, Jimi Hendrix and The Doors. Joni Mitchell was great, and Miles Davis, of course.”

People heckling the performers, fans breaking down fences and entering free of charge, anarchists disrupting the proceedings, a fire over the stage, and festival organisers being in well over their heads were just some of the ‘highlights’ of Isle of Wight 1970.

As a result, there wouldn’t be another festival on this tiny island off the south coast of England for quite a while. Another 32 years, in fact.

The first Isle of Wight Festival took place in 1968, supposedly when the island’s swimming pool association needed to raise money, and the idea of holding a pop event sounded like a splendid idea. The 150-acre Hayles Field (dubbed Hell’s Field) was secured, and over two days 10,000 people saw performances by The Move, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Jefferson Airplane and Arthur Brown, among others. The festival was such a success that its organisers – the Foulks brothers, Ray, Ron and Bill, together with Rikki Farr – decided to stage another one.

With the organisers having convinced Bob Dylan to come out of exile to play his first show in years, and with The Who, The Moody Blues and The Band also on the bill, 1969’s three-day Isle of Wight Festival attracted a huge crowd of 100,000, with members of The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and Pink Floyd among the VIPs.

Even though the second show had been massively bigger than the first, no one could have predicted the number of people who would turn up in 1970, when the festival took place over five days and featured some of the biggest names in rock, including Jimi Hendrix, The Doors and The Who.

Expecting a bigger audience still, a new festival site was scouted and the organisers settled on Afton Farm. But there was a problem – it was overlooked by Afton Down, a hill that offered a perfect view of the stage. It was obvious that thousands would congregate and camp out on the hill rather than pay to get in, but the site was chosen regardless.

Murray Lerner had directed the 1967 movie Festival!, which chronicled the highlights from several years of the Newport Folk Festival in the US – including Bob Dylan’s first-ever ‘electric’ performance.

By 1970 Lerner was ready to document another outdoor music spectacle on film, and he hooked up with the Isle of Wight Festival. Almost immediately after filming began, Lerner detected an unexpected ‘vibe’ surrounding the event. “I think that whole movement began to break apart,” he said.

“The kids got upset about the commercialisation that was going on. When you get a crowd of that many people, and one guy starts: ‘Let’s get in for nothing,’ there’s a ripple effect. So they all wanted to get in for free by smashing the fences.”

Lerner also recalled that there was “a lot of trouble in terms of the crowd. There were no fatalities [yet]. There was the fire, which we show [in the film]. It was just a guy who was told two weeks earlier to schedule fireworks. And without thinking, he shot them off, and everyone thought, ‘Okay, the stage is being attacked by flame’ [laughs]. I thought that was it.” Luckily the fire was soon under control.

The first two days of the 1970 event – August 26 and 27 (a Wednesday and a Thursday) – saw performances by mostly newer artists, including up-and-comers Supertramp and Terry Reid.

But it was another relative unknown who left a big impression on Lerner: “David Bromberg received a phenomenal reception from the audience. When he got off the stage he said: ‘I’m a star!’ You would’ve thought that Bromberg was going to be the biggest star in the world that night. I think he had four encores.”

On the Friday, by which time the attendance was reaching its peak (said to be 600,000), US band Chicago put in one of the first really outstanding displays of the festival. Although years later they became known as pop balladeers, back then were a jazz-infused powerhouse rock band with a blazing horn section that set them apart from the pack.

Chicago’s sax player, Walter Parazaider, recalls the events leading up to their set: “They had us in a holding area, with cottages and everything, which was just spectacular. The weather was great. Isle of Wight was our first experience of [playing festivals]. And you talk about people being really young – eyes as big as silver dollars, and taking everything in.

“The whole spectacle of it was amazing. It was massive. When you get that amount of people, just a whisper from a crowd is a roar. If you don’t keep within yourself, you could just as easily throw your horn in the crowd and run around like a lunatic, just freaking out.”

But Parazaider and the rest of Chicago needn’t have worried. “The crowd was very receptive,” he remembers. “That first album [1969’s Chicago Transit Authority] had I’m A Man on it – a Spencer Davis Group tune – and it had gone over quite well in England. They knew the material, and we were quite well received. It was one of the highlights of our career. It was a knockout.”

Procol Harum and The Voices Of East Harlem played later the same day, before headliners Cactus closed the Friday with a hard rockin’ set. Cactus drummer Carmine Appice recalls that the festival’s main attraction, Jimi Hendrix, had turned up early.

“The thing that I remember the most is the fact that we were hanging out a lot backstage with Hendrix,” Appice says. “Everybody had little areas where they hung out. I remember a lot of jamming going on, with guitars and lots of banging on tabletops. At these festivals there was always a lot of drugs. We used to drink a sip of wine backstage, and you didn’t know – sometimes it would have mescaline in it or something weird. Everybody was smoking pot.

“It was cold, it was rainy. I think it was damp and foggy. I think the Isle of Wight was a bit of a disaster. That was the drag of being a headliner of those kind of festivals – by the time you go on it’s like the wee hours of the morning and your audience is going away. Look at Hendrix playing Woodstock – he had nobody there. Whereas Santana played when the place was packed.”

We used to drink a sip of wine backstage, and you didn’t know – sometimes it would have mescaline in it or something weird.

Carmine Appice, Cactus

Saturday, August 29, had the most acts during a single day, with 12 very varied performers. Perhaps it was too varied. With most of the huge crowd geared up to rock to the likes of Hendrix, The Who and The Doors, when folk singer Joni Mitchell hit the stage early, trouble was brewing. A clearly ‘out of it’ guy who had got up on stage uninvited was forcibly removed. The crowd voiced their disapproval.

Murray Lerner: “There was a famous scene where the crowd was yelling and keeping her [Joni] from singing. She decided to face-down the crowd, and was playing the piano, vamping, and almost crying. [Joni] said to the crowd: ‘We’ve put our lives into this stuff. You’re acting like tourists.’ That changed the whole tone of it. She called the crowd ‘the beast’ and she decided to face them down. She had had problems with other places and had given in. But she decided in this case not to.

“I would say it was always on tenterhooks,” Lerner continued. “Was the crowd going to rush the stage? If they did, that would be the end. I was always worried about that, but they never did. It was really frightening when Joni was on. It’s hard to imagine when you have that many people in front of you, I can tell you that. I was always worried, because I didn’t understand what a crowd was until that festival. Then I realised there is nothing you can do – if the crowd moves, than it’s the end. You saw it in the Cincinnati thing [when fans were crushed to death trying to get into a Who concert in 1979].”

Although Lerner pointed out that Mitchell had earned the crowd’s respect by the end of her set, their hostility prevented what could have been a festival highlight.

According to the book The Visual Documentary by John Robertson, Neil Young was going to duet with Joni but changed his mind after witnessing the friction. Young left the festival before the end of Joni’s set.

With the crowd on edge, following Joni with Tiny Tim – an oddball bloke best-known for strumming a ukulele and singing in a warbling, irritating falsetto – might not have been a particularly good idea. But… “The audience went wild for Tiny Tim!” Lerner said. “Because it was like a campy reaction. You would have thought he was the biggest star in the world.”

Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull (who played the following evening) remembers Tiny Tim at the Isle of Wight for a different reason: “I’ll always remember Tiny Tim refusing to go on stage until he had the money in cash in a briefcase, at his feet. Not exactly in the spirit of the age.”

With the crowd now mellowing, legendary jazz trumpeter Miles Davis – in the midst of his groundbreaking jazz-fusion period – had the crowd in the palm of his hand.

"Miles Davis was a surprise – and really unusual. It was a revelation,” Lerner said. “The crowd really liked it. He went on, played, waved his hand at that audience and walked off. He played for approximately 38 minutes straight, without stopping.”

After some much-needed good-time blues rock from Ten Years After, the newly formed Emerson, Lake And Palmer played what was only their second-ever gig.

“The enduring memory is the actual physical sight of that many people,” ELP singer/bassist Greg Lake recalled of Isle of Wight 1970. “I suppose before that, the only other time you’d see that many people gathered together would have been a war. The night before, we’d played to something like 1,000 people. The next day it was 600,000.”

Lake also remembers that the festival didn’t exactly reflect the peace and love vibe that had characterised Woodstock.

“There was a kind of random chaos taking place. In a way, it was all meant to be relaxed and ‘peace, love and have a nice day’, but there was kind of a tension about the whole thing.”

Despite the lack of good vibes, ELP went down well with the crowd, perhaps because with their keyboards-heavy sound and classical leanings they delivered something a bit different. The band did have one dodgy moment, however, but managed to avoid an explosive – literally – situation that could have been disastrous.

“We decided to fire these 19th-century cannons at the end of Pictures At An Exhibition – to emulate the 1812 Overture,” Lake explains. “Unknown to us, the road crew had doubled the charge in the cannons. All I can remember was seeing this huge, solid-iron cannon leave the ground! It blew a couple of people off the stage. Luckily there was no cannonball in it. Thank God!”

In a similar way that Santana’s electrifying performance at Woodstock catapulted the then-unknown band to overnight stardom, ELP’s show-stealing performance at Isle of Wight gave the newly formed supergroup a huge career boost.

“After that festival, the very next day ELP was on the front page of every music newspaper,” Lake remembered. “It was indeed one of those overnight sensations.” After ELP and their cannons, next up came one of the festival’s big guns – The Doors. Then in the midst of singer Jim Morrison’s Miami trial (for allegedly exposing himself on stage), the band had been granted permission to leave the US briefly to perform at the festival.

Lerner recalled: “Jim Morrison said to me: ‘I don’t think you’re going to get an image, because our lights are low. We’re not going to change it.’ But in fact I got some beautiful images by looking into the light and making it look surrealistic and abstract.

“The Doors were hypnotic but they had to leave right after their performance – they were on trial in Miami. They were let out just for that performance. So they had to leave right away.”

If the crowd had been hypnotised by The Doors, they were walloped back to their senses by The Who. Still plugging their Tommy album, Pete Townshend and co put in a stellar performance that is now considered a career high point for the band.

“The Who’s performance was really fantastic,” Lerner enthused. “A great, theatrical presentation, with huge spotlights behind them that dazzled you. The ending of Tommy was really incredible. And Naked Eye was great.”

“And of course, Keith Moon was fantastic – playing around and having fun. He was in good shape while he was playing. I don’t know what happened afterwards [laughs].”

If the promoters were indeed attempting to model the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival after Woodstock, this was the night that it became quite evident, as three Woodstock veterans closed the evening’s entertainment: The Who, hippy-dippy folk songstress Melanie and US funksters Sly And The Family Stone. The latter were by now one of the world’s top acts, mixing social commentary in songs that appealed to both rock and dance fans.

Family Stone sax player Jerry Martini recalls that the fans were receptive to his band. “It was good. I just remember us playing our concert, going over well, and having a great time at the nightclub they had there – it was jam-packed. I remember leaving that with a good feeling.”

While Sly And The Family Stone’s performance at the Isle of Wight went off without a hitch, Martini admits that it wasn’t quite as magical as a certain previous performance. “I don’t think it was as good as Woodstock for us. Woodstock did the most for us, but it was way up there.”

Sunday, August 30 was the final full day of performances, featuring the man who many considered to be the absolute headliner of the whole festival: Jimi Hendrix. In the morning, an ill-advised attempt was made to clear out the huge number of people who’d gathered for Jethro Tull’s soundcheck, to ensure that those without a five-day ticket would have to pay.

Lerner: “The attempt to empty the arena was really funny. It was impossible. They said: ‘They’re not going to do a soundcheck unless you leave. Then [Tull manager] Terry Ellis said: ‘Don’t tell them that, because we don’t care if they’re here.’

“They tried all sorts of things to try to get rid of the people, but they couldn’t. They were saying stupid things. And they thought the radicals were French, so the announcer said: ‘Does anyone speak French?’ This girl came, and spoke French very crudely, so the whole crowd was sniggering. She said: ‘Those who have tickets, burn your tickets, and then we’ll know you have a ticket.’ It was stupid. You’re talking about 100,000 people. They weren’t going to leave easily.”

Soon the crowd was throwing debris at the stage.

It was around this time that a van full of young hopefuls pulled up to the festival site. It was space rockers Hawkwind, who asked if they could play an impromptu set. The organisers said they could – but outside the festival perimeter.

Hawkwind leader Dave Brock remembers the day well: “What you’ve got to remember is the Isle of Wight has some lovely chalk cliffs. But the actual festival itself had all of these big corrugated sheets, like a prison camp. Outside the festival there was this big canvas city, at the centre of which was this gigantic inflatable tent. It had a generator running it, and the whole thing gradually inflated up. But then the generator ran out, and the tent started sinking down!

“Jimi Hendrix came in to see what was going on. Our saxophonist [Nik Turner] had his face halfpainted silver. I think in Hendrix’s set Jimi dedicated one of the numbers to ‘the guy down in the front with a silver face’, which was Nik. Nik got around to talking to him and asked him if he’d have a jam with us. But by the time he got there the tent was deflating and people were all standing with their hands up trying to support it – it was about eight foot high.”

Brock also recalls drugs being passed around freely: “We all took loads of LSD. Our lead guitarist, Huey [Huw Lloyd Langton], freaked out badly. He’d been spiked up on some orange juice. Unfortunately I had some as well. Suddenly I had this great rush come over me – I was all tingly and peculiar. I had this lady with me, who took me away up to the cliff tops for a walk to try and calm me down.”

And then there was the bedlam going on outside the gates. “There were a lot of anarchists,” Brock says. “They were all saying that when the festival has made enough money, then the fences should be destroyed. They started ripping the fences down. People threatening each other and all that. There were about 10,000 people outside.”

Back inside the festival, an early standout performance of the final day was that of Free, who were supporting their now classic Fire And Water album.

Murray Lerner was just one of many who was knocked out by the British blues rockers. “To me they were a revelation,” he enthuses. “I had never heard them before. I thought they were fantastic – their energy, their sensibility. And All Right Now to me was really a thrilling song.”

Soon after Free’s set, another British band also impressed Lerner – The Moody Blues:

“It was at twilight, and the lighting was unusual. I liked the singing – it was more melodic than most of the other groups. Especially Nights In White Satin. They were sympathetic to the crowd – that I remember quite well. And the beauty of the light at the time they performed was amazing.”

Still tripping, Hawkwind’s Dave Brock recalls making it into the main area in hope of catching The Moody Blues’ set: “After the fences came down, we actually went inside there to see some of the bands. I’d been given a Mandrax – a sleeping tablet to calm me down. I fell asleep, which was a bit of a shame, because I was quite looking forward to seeing them.”

Anticipation for Hendrix’s performance was high and building. But before Jimi it was the turn of Jethro Tull. Leader Ian Anderson’s memories of the festival are not very fond ones, despite the band putting in a strong performance: “Things were going around both backstage and front of house that made it a little unpleasant for everybody. It was out of control, and the organisers were struggling to keep the thing from degenerating into something quite horrible. It was perhaps a testimony to the local police, and generally the welcoming residents of the Isle of Wight, that the thing happened at all.”

Interestingly, it was Tull’s refusal to play Woodstock that set up their Isle of Wight appearance.

“We were invited to play Woodstock and didn’t,” Anderson says. “Mainly because I didn’t want to spend my weekend among a bunch of unwashed hippies. It was too much of a defining moment for a brand new band. It would have been the beginning and the end for us – as it was for Ten Years After. As it turned out, I think it was a defining moment in that change from the hippy ideals to the rather dark and pragmatic side of music.

“At the Isle of Wight we knew we were unlikely to get paid, and we determined early on that this was something that we really just had to go through and try and keep a modicum of a smile on our faces. So we just kind of got on with it and did our bit. It was not a good gig, it was not a bad gig, it was just a little frenetic and a little tense.”

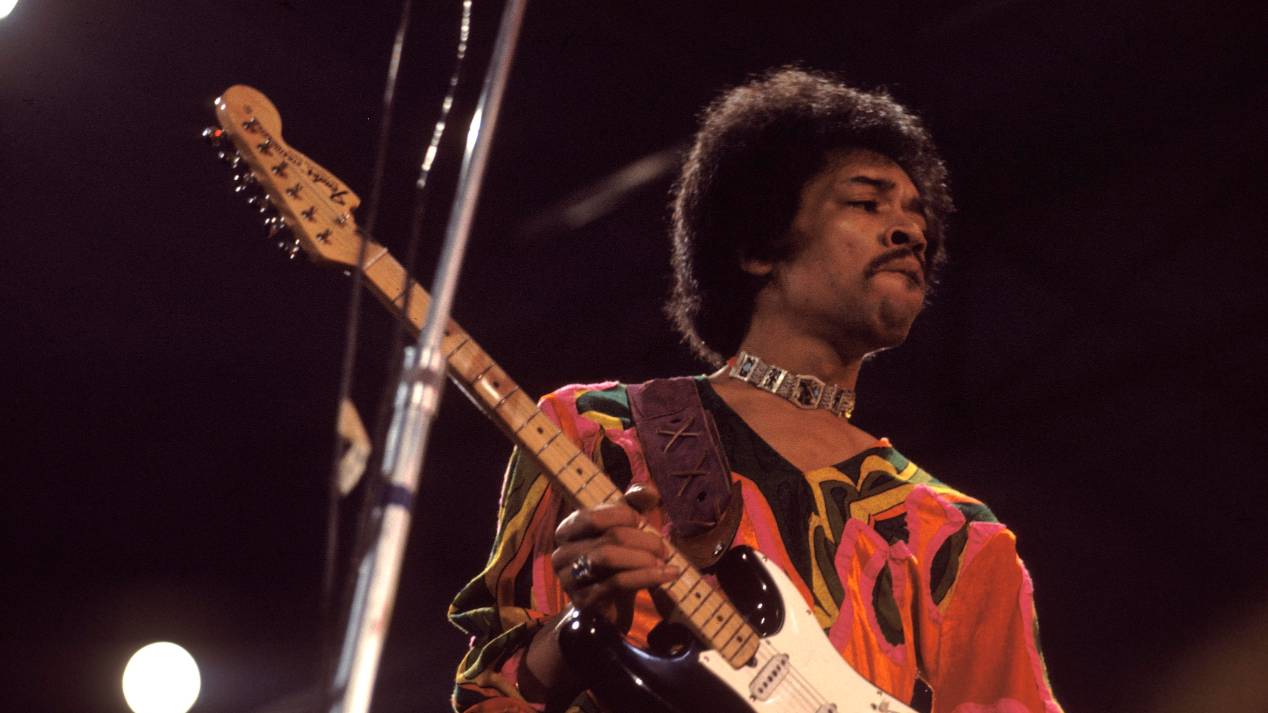

Not long after Tull had finished playing, the compere made an announcement that sent a palpable wave of excited anticipation through the crowd that had stayed on: “Let’s have a welcome for Billy Cox on bass, Mitch Mitchell on drums, and the man with the guitar, Jimi Hendrix.”

Finally, the performer who many had come to the festival to see, over and above anyone else, launched into what became an almost two-hour set. But – as evidenced by the 2002 DVD Blue Wild Angel: Jimi Hendrix Live At The Isle of Wight – what was expected to be a dazzling, thrilling performance fell very short of that.

Clearly, worryingly, something was wrong. Watched on the DVD, Hendrix appears dazed, distant; almost every song includes meandering guitar improvisation; vocal lines are fluffed. Additionally, Hendrix was constantly consulting with roadies instead of concentrating on his band’s and his own performance.

As The Who’s Pete Townshend reminisced in the 2001 DVD 30 Years Of Maximum R&B Live: “What made me work so hard was seeing the condition that Jimi Hendrix was in. He was in such tragically bad condition physically. And I remember thanking God as I walked on the stage that I was healthy.”

Lerner, however, disagreed: “I didn’t think he was in bad shape, I just thought he was tired,” he said. “He did great renditions of Red House and Machine Gun – which I think is as good as anything he’s ever done. Although admittedly he didn’t give the usual wild, waving around [performance].

“Before he went on, Jimi said: ‘How does God Save The Queen go?’ And then he played it. He said: ‘Everyone stand up for your country and your beliefs, and if you don’t, fuck you.’ Machine Gun is always great, but in this case [Hendrix said]: ‘Here’s a song for the skinheads in Birmingham. Oh yeah, and Vietnam. I almost forgot about that.’ Machine Gun goes on for about 17 minutes.”

Sadly, Jimi’s performance at Isle of Wight would be his last on British soil. Just over two weeks later he was dead, aged just 27.

Although many people continue to assume that Hendrix closed the festival, he was actually followed by performances from Joan Baez and Leonard Cohen, who played into the early hours of the following morning, before Richie Havens closed the whole thing at daybreak.

Lerner recalled the final performers. “[Cohen] said some very nice things about the radical movement of the time: ‘We’re a small nation, but we’re going to grow. We need our own land.’ I remember he had a lot of beautiful women singing with him – I was jealous. He had that kind of attraction, I think – the suffering poet [laughs].” “I don’t consider [Havens] the last, because he played at dawn. For me, the last was Cohen. I think [Havens] wasn’t on the stage – he was walking around singing off the stage. Singing at sunrise. It was extremely moving.”

With the end of Havens’s set, many of the remainder of the dwindling crowd made their way to the exits – bleary-eyed, hungry and unwashed. Although catastrophe seemed to hover over the festival throughout, it never came to a head. There would be many other British festivals in the wake of the turbulent 1970 Isle of Wight, and they continue today. But it was clear that such gatherings could not get by merely on the 60s peace and love ethos.

From now on, rock festivals were now big business, and, for many of those involved, money was now the star attraction.