Daniel Cavanagh is a little like a ticking time bomb. Exclamations come sparingly, without warning, but when they do, they punctuate sharply his otherwise soft Scouse tones. “Get in the back of the van!” he shrieks at one point, on a particularly enthused Withnail And I quote. Anathema’s guitarist/keyboardist/lead songwriter isn’t much over five-and-a-half feet, but his Sideshow Bob shock of curls and propensity for leaping up off the black sofa at the North London HQ of their label, Kscope, give him a few extra inches.

Such intensity is apposite given the scale they operate on these days. Formed nearly 25 years ago in Liverpool by Cavanagh and his singer-guitarist brother Vincent, Anathema have made the unlikely journey from guttural doom metal upstarts into a more progressive, adventurous beast. Their quietly epic music – as embodied on recently released tenth album _Distant Satellites _– is the closest you’ll get to a modern-day Pink Floyd, in spirit as well as sound.

Since the beginning they’ve been fuelled by the Cavanaghs’ deep, sometimes fractious sibling relationship. On stage, Daniel’s upfront persona is offset by the more introverted, intense demeanour of his younger brother; off stage, the roles are seemingly reversed. Those family dynamics have often informed the guitarist’s songwriting, not least the death of their mother in 1998 (their father has since passed away). Their music is informed by a deep sense of discomfort and some unflinching autobiographical lyrics that are often at odds with the celestial ambience of their songs.

“I’m a complex person and my childhood was difficult, so it comes out,” Daniel admits. “And it’s maybe partly genetically inherited. My dad was pretty fiery too, to say the least.”

The Cavanaghs grew up in Anfield, during the glory days of Liverpool FC. It was a bittersweet upbringing, however, with their home life often proving turbulent. Music became something of an antidote. “I didn’t fit in too well at school,” Daniel concedes of his time at Liverpool’s prestigious Blue Coat grammar school (Vincent attended the local comprehensive with his twin Jamie, also Anathema’s bassist). “I had a circle of friends, but I stopped playing football and hanging around with people.”

Instead, the young Dan spent his lunch breaks teaching himself to play the school’s grand piano. “We couldn’t afford a piano at home,” he says. “And I don’t mind admitting I was heavily bullied in that school. So I just retreated into the piano, and when I got home I retreated into the guitar. I put my head down, started playing, looked up and four years had passed.”

As Daniel hit his mid-teens, he began to make music with Vincent and Jamie, together with aspirant drummer John Douglas and singer Darren White. Metallica and cult British death metal band Bolt Thrower were among their early influences, though Daniel would quietly draw inspiration from the likes of Marillion, Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler and even Queen – even if the latter weren’t evident on their early albums for UK underground label Peaceville.

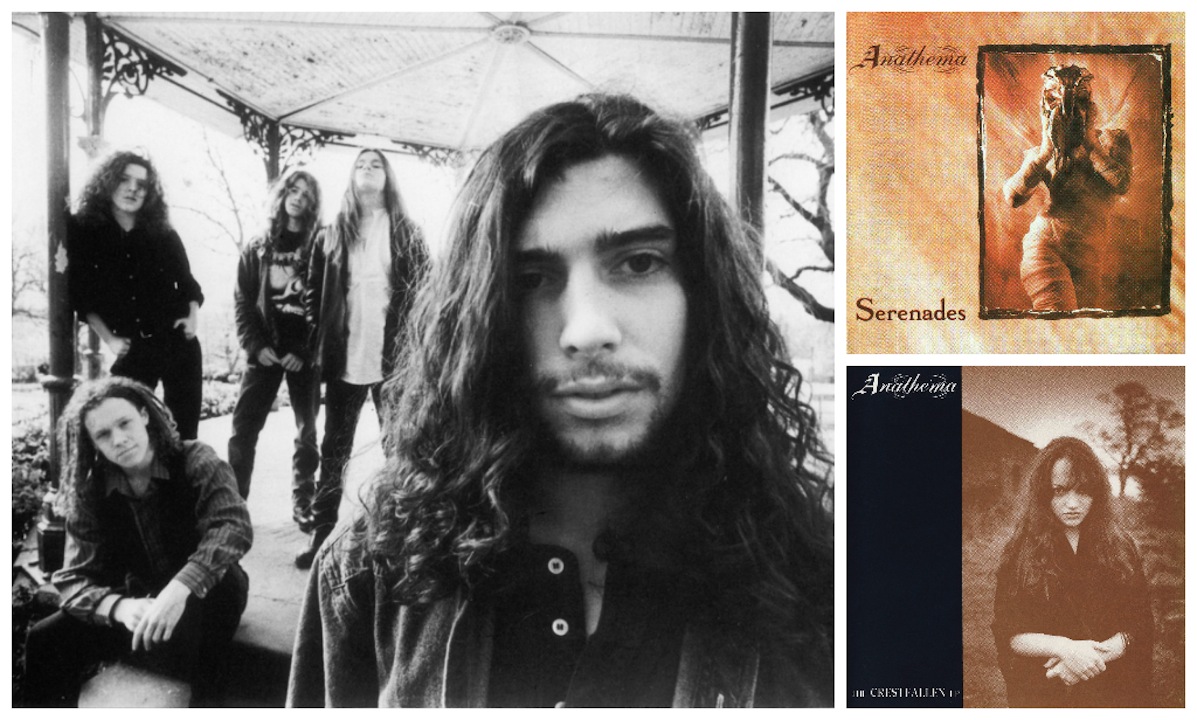

“Obviously when you get into metal and you’re a teenager, you want everything to sound super heavy, hence [1993 debut LP] Serenades,” he says. But there were already glimpses of what was to come, not least in the title track of 1992’s The Crestfallen EP, with its brutally confessional lyrics: _‘The darkness eats away at the very embers of my soul.’ _

By 1995, with Darren White gone and Vincent stepping in as frontman, Anathema’s transformation truly began. By 1996’s spacey, fluid Eternity, they’d shaken off the last vestiges of their gnarly metal past (their progressive credentials helped by a cover of Roy Harper’s Hope). Three years later, the loss of the Cavanaghs’ mother fed into their fifth album Judgement, its soaring, atmospheric sound opening up a new chapter for the band – a course they remain on today. For all their Floydian ambience and emotion, they remain rooted in reality. “We don’t make up stories, we don’t paint pretty pictures,” Daniel says. “It’s our lives, it’s all real.”

This sort of intensity is typical of the guitarist. “The point is that we love each other,” he says at one point. “Love is the gravity that keeps all these satellites in orbit.”

This isn’t to say that these satellites haven’t occasionally swerved off course. Daniel left Anathema for a spell in 2002, briefly joining former Anathema bassist Duncan Patterson in goth-tinged project Antimatter. I ask him if there have been times when band relations – and more specifically sibling relations – haven’t been entirely rosy. He bristles at the suggestion. “I’m not gonna answer that,” he says darkly. “Cos you’re digging.”

He does concede that his relationship with Vincent became stronger when the pair embarked upon an acoustic tour in 2003, having split up from their respective then-girlfriends. “We’ve had our ups and downs, but there hasn’t been a major problem.”

Around the same time, Daniel quit drinking and began intensive hypnotherapy sessions. Today, he’s given to saying things like: “The fundamental question should be: does consciousness survive death? And if it does, that changes everything. The implications of that are enormous. And if you research near-death experiences, which I have done extensively, and spiritual states… you access the real deeper states within yourself.”

He doesn’t enjoy sitting in pubs any more, and yet they remain a powerfully tight group. “To this day I am still a happier person every time John’s in the room,” Daniel smiles. “And Vinnie has been a rock – my number one confidant in life.”

Vincent Cavanagh is taller and broader than his older brother. He greets us at the Métro stop nearest to his Paris flat – he’s been a resident of the French capital for a couple of years. Dressed in all-black jeans, boots and leather jacket, hair scraped back into a knot, he looks like an arty biker as we head along quiet, cobbled streets. The effect is shaken only a little by a pit stop for cat food; “I love ’em to bits, but they end up running your fucking life,” he chuckles shyly.

The house he shares with his French girlfriend Sarah is similarly arty. Half Indian palace (complete with gold domes on the roof), half converted church, quite unlike the scruffy, grey Parisian blocks nearby, it looks out upon grapevines and green allotments, and on down to the Seine. The stereo veers between 65daysofstatic and The Beatles while he prepares salmon for lunch. “I like having a base to come home to these days,” he says of his artistic but homely set-up.

Sarah’s Parisienne roots, and the artistic history of Paris, are what lured Vincent here. The connection with his UK-based brothers and bandmates, however, is in good shape following an intensive few months in Norway, recording Distant Satellites. “There’s a deep bond of brotherhood with these people,” he stresses, sipping a post-lunch Corona in the lounge. “The band could end tomorrow and I wouldn’t give a shit as long as I was in touch with Danny and John and everyone.”

For all their strong opinions and personality contrasts – they share a lot of the same intensity – he and Daniel have never had serious problems with each other. “I’m maybe on a more even keel than Danny,” he says. “Me and Jamie have never had an argument in our lives, but in a way I’ve got a deeper connection to Danny because of the kind of people we are. We’re both very driven, we work hard and we’re always thinking about music. We can’t stop.”

The younger Cavanagh is marginally franker about the aggressive nature of their childhood. “I don’t want to go into specifics, but we grew up in a violent household,” he tells us. “Which taught us quite a few lessons about how not to be. But if I think about it now, it raises that philosophical question of, ‘Would you change any of those difficulties you had in the past?’ You’ve been through all this, but on the flip side, you’ve learnt a hell of a lot more.”

Growing up “around smackheads” in Liverpool ensured that heroin was stripped of any rock’n’roll glamour in Vinnie’s eyes. “There’s certain people out there that will romanticise this idea of the elegantly wasted heroin addict who’s a creative, a poet – and it’s bullshit.”

Through all this he’s immensely loyal to his older brother; protective even. “I remember when we were kids, any time Danny got upset he’d go to his bedroom, crank that amp up, and the whole street could hear it,” he remembers. “That’s where the music comes from, y’know. It comes from right back there in that fookin’ house when we were kids.”

Nevertheless fond memories grew out of Anfield life, despite the harder times – football being an enormous saving grace. “FA Cup final day was a good one,” he enthuses. “The street would have a party and everyone’d be happy.”

Many a day was spent playing footie in the park, or at John Douglas’s home. “His mum and dad were nice – they had a nice house, they used to make me sandwiches,” Vincent says fondly.

And from these good times emerged initial recording sessions, using a Fisher Price tape recorder. “That was our first recording studio!” Vinnie beams. “And we’d just make noise, stuff to make each other laugh. But about a year and a half after that we had a fucking record deal, which is just bizarre!”

Both brothers absorbed classical music through film soundtracks, Samuel Barber’s Adagio For Strings (from The Elephant Man) being a favourite of Vincent’s. And while Dan branched out into the likes of Metallica, 17-year-old Vincent was introduced to the electronica of Aphex Twin while working at a local studio. Still, listening to his exquisite vocals today, it’s strange to think he never wanted to be a singer. With a grounding love of beats, his ambitions lay in drumming. Upon White’s 1995 departure, Vincent was “forced into the position”. Some fraught initial efforts followed, but everything fell into place by 1998’s Alternative 4.

“Inner Silence [from Alternative 4] reminded me of the soul tracks I used to listen to when I was a kid. We’d be round at me aunty’s, they’d be having a few martinis and listening to some dead sad soul. The Commodores, Otis Redding…”

It evokes memories of his mother, a big soul fan with a penchant also for early Fleetwood Mac. Albatross, he tells me was played at her funeral. “It’s one of those that’ll stay with me; I have a mix of tracks like that, stuff from when I was a kid, classical, electronic.”

He scratches the kitten’s head. It scrambles onto his knee, clinging in slight alarm as Vincent laughs loudly: “I can imagine being 85, saying, ‘I just want to hear [Aphex Twin’s] Windowlicker one more time! Just one more rave!’”

Suddenly he seems like his big brother. A more relaxed, maybe happier version, but bound to the same intense relationship with music. The same single‑minded need to write songs that’s seen them evolve through weighty, dreadlocked doom to innovative, blissful rock. Only now, they have the technology and experience to truly capitalise on the ambition that’s been brewing for so many years.

“Looking back at our discography, it’s an interesting evolution,” Vincent agrees. “But it’s only now that we’re able to produce some of the music we’ve had in our heads for so long. And we can make it sound good, too.”