Andy Fairweather Low first gained attention fronting the cutesy pop-rock band Amen Corner in the mid-60s. From their ashes came a proggy outfit called Fair Weather in 1970. Soon after, he was solo, and toasted a big hit single with the soft-rocking Wide Eyed And Legless in 1975. But the Welshman’s agility as a singer/guitarist sideman connected him to peers including Eric Clapton, and he’s had a long career as superstar support for Roger Waters, George Harrison and Bill Wyman, among others. As a teen he learned the ropes with songs such as Bessie Smith’s Gin House Blues, which Amen Corner covered for their first single release. Bringing him full circle, the song is included on his latest album, The Invisible Bluesman, a collection of vintage covers.

Jimi Hendrix

On tour with him in 1967, I was nineteen and witnessing this thing first-hand, two shows a day. Sometimes, when he got to Wild Thing at the end of the night, tuning-wise it was wild. Amen Corner had residencies in London at Blazes, Tiles and The Speakeasy, playing soul and R&B. If you were in a band, you’d hang out there. One night Jimi was there and decided to play I Can’t Turn You Loose, with us. He borrowed Clive [Taylor]’s bass, turned it upside-down and took it from there. A few months later he got up and played Neil Jones’s guitar. I decided to play bass, until he turned around and said I was playing in the wrong key. I had no idea what key it was in!

A little later, I’m in New York, staying with our manager Terry The Pill, who worked for Hendrix’s manager Mike Jeffery. We get a call – could I come to the studio to do some backing vocals? When I go over, Jimi’s recutting Stone Free and Roger Chapman’s there. So you have Larry The Lamb and Archie Andrews on backing vocals. Jimi was a quiet, lovely, polite man.

Pete Townshend

I first saw Pete with The Who in 1965/66, as a punter at the Porthcawl Pavilion. He is one of my all-time heroes. I was staying with Glyn Johns while he was working on Who Are You. Pete said: “Tell Andy to come and do some backing vocals.” I did about five tracks, the first being the title track. In 1993, while Pete was drying out in the US, I was asked to join The Who for a few months until he came back. When he returned, I stayed on, but after a few days I realised I wasn’t needed so I said: “I think I’ll go and play tennis.” Then Pete’s Psychoderelict album came out in 1993, and he asked me to tour with him in America. That was a really interesting event, a musical with actors like Jan Ravens. I learned a lot from Pete with his chord shapes and songwriting.

Roger Waters

In November 1967, Amen Corner played our first tour ever on a bill with Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd, The Move, The Nice, Heir Apparent and Outer Limits. We were all in one bus apart from Floyd, who travelled on their own. Our manager, Ron King, overheard one of them say something about our keyboardist Blue Weaver, and he threatened to break their legs. They’d open with Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun, and it would completely baffle me, like: “What are they doing?” One day in around 1984 I get a call: “Hello, Andy, it’s Roger Waters.” Who? I hadn’t paid attention to their names. He asked me to come up and see how we got along, with a tour for The Pros And Cons Of Hitchhiking in mind. I went to see him, and we didn’t just get along, we talked all about the tour. I played with him for about twenty-four years. He treated me with unbelievable respect, was superb company and very funny. And you know what? Set The Controls became my favourite thing to play live [laughs]!

BB King

I was in Los Angeles in the eighties for a record company meeting, went to a club, and BB was playing there. I stayed behind and got his autograph. All of a sudden, Eric’s gonna do an album with him, Riding With The King, and we go out to Santa Monica. The hotel’s on the beach, I get to go in the studio for a month, and every day BB King is in there. The whole time I was there he never called me by my name. It was enough to be part of it in the band. To use a Roger analogy, he was one of the first bricks in the wall.

Eric Clapton

I was a big fan of Eric and used to have a poster of him in Blind Faith at Hyde Park up on my wall. When I was in Amen Corner I decided I was never going to be good enough to be him, but I could make a living pretending to be Steve Cropper. Then when I got my solo deal with A&M, my second album [La Booga Rooga] was produced by Glyn Johns, a really good friend. He then produced Eric’s album Slow Hand [1977] while I happened to be staying at his house. I met Eric then, and during the recording of Backless I was sitting in the control room being a pest and a fan. I was having trouble with my label. Glyn told Eric, and he sent me a telegram of encouragement. I couldn’t believe it. Eric asked me if I’d join him in the winter of 1990 to 1991, at the Albert Hall. I went: “You serious?” This was a life-changing moment. I’d work with Eric for thirteen years. I loved it – all the sound-checks, the rehearsals, the album recordings. I love his voice, too. And he’s introduced me to so many fabulous musicians. I’m so proud of what we’ve done together.

Joe Satriani

I was playing at the Fillmore West on a blues tour with Eric and, unbeknown to me, Joe was in the audience. Glyn Johns was going to record a live-in-the-studio album with him [self-titled, 1995], and Joe had never recorded live. Glyn suggested me as rhythm guitarist. I went: “Joe Satriani? Me?” Glyn said: “I think you can do this.” I said: “Give me his number!” I called and said: “Joe, you do know what I do…” And Joe was like: “Yeah, I saw you with Eric.”

I end up in the studio with him, about four feet away, and I can’t think as fast as he can play. Phenomenal control, knowledge, and a lovely man too. He showed me a part for the track Luminous Flesh Giants that went ‘da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da’, then he’s off somewhere else. But I thought to myself: “I can do the da-da-da-da bit!” I could also do a part that was one note for the track Killer Bee. I arrived with a certain amount of guitar noises that I had, and I thank Joe for holding my hand with that record.

Tom Jones

In all my time on the circuit from the 1960s, I never bumped into Tom Jones at all. In 2015 I get a call from Ethan Johns, Glyn’s son, who’s doing an album, Long Lost Suitcase, with Tom. He would like me to play guitar on it. Yeah, absolutely! It was bluesy, soulful, a bit of rock, a step away from Delilah, or It’s Not Usual – which I bloody love, by the way. We went to Free House studio in Bristol, owned by James Dyson’s son Sam, incredible place. We recorded like they might have done in the fifties; I’d sit by my amp, and Tom would be in the middle of the room on an old RCA mic. I did backing vocals on one of the tracks. Tom has sung with Little Richard, everyone. I told him: “Finally, you got to sing with me!” [laughs]. A warm, down-to-earth man to play with, and Ethan captured some of my best guitar work.

Edie Brickell & Paul Simon

One of the connections I had through Eric was with Steve Gadd. Steve had worked for twenty-five years or more with Paul Simon. He knew Paul’s wife Edie, and was going to produce an album for her. He said: “Do you fancy being on it?” So there’s me, Steve on drums and bassist Pino Palladino – another proud Welshman – and we’re called The Gaddabouts. We do one album [self-titled, 2011], then we do another [Look Out Now!!, 2012]; Edie is the most prolific writer. Most of the stuff I played, the riff came from her.

One time, I lost my porkpie hat, a treasured possession, travelling to New York from Heathrow. Paul Simon comes into the session and says: “Andy, where’s your hat?” I told him I lost it on the train. Four days later, Edie says: “Someone wants to see you, go outside.” It’s Paul, and he’s got a couple of hats which he tries on my head. “That’s your size,” he says. And he gets this company in New York to make me a hat! He also came in to record with the harmonica from The Boxer, which I played for a fairly simple part. I had to gaffa tape the holes to make sure I played the right notes.

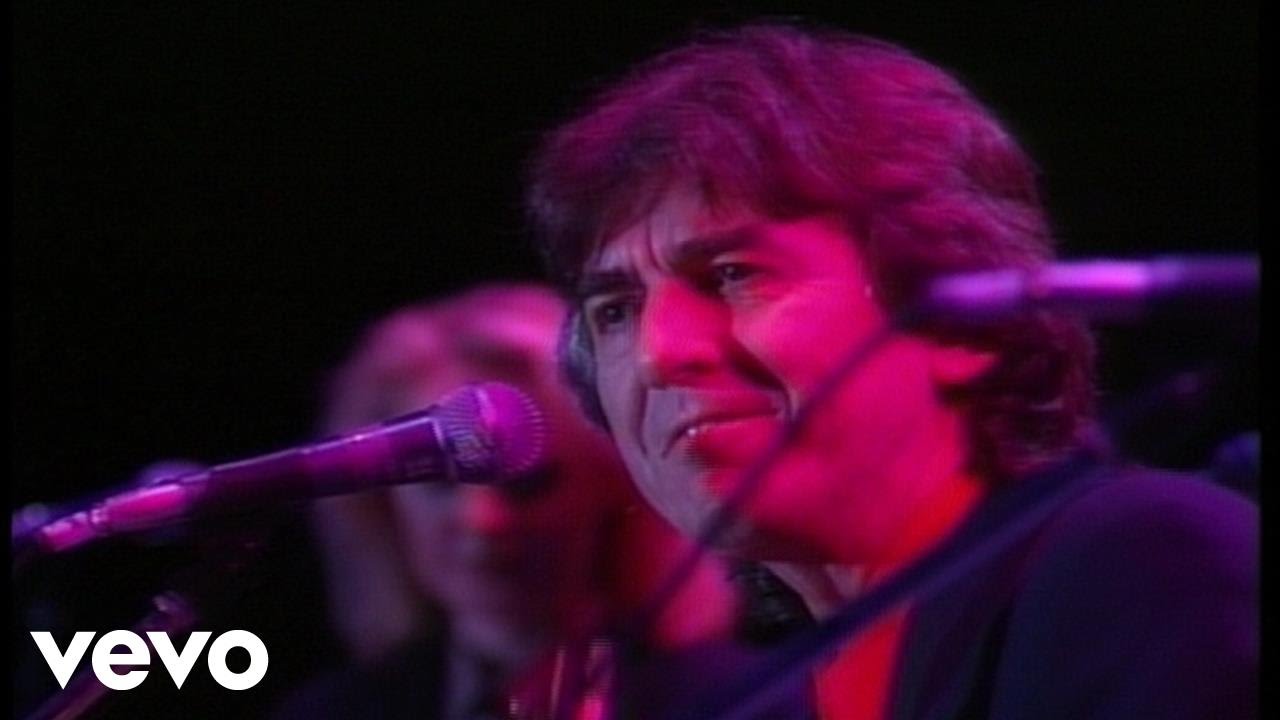

George Harrison

I could never get “Wow, he’s a Beatle!” out of my head when I was working with him. It all started after his manager, Roger Forrester, had been in touch to tell me that George would like me to play slide guitar during his Japanese tour. I said: “I don’t play slide because I can’t be as good as Ry Cooder. Give me George’s number to explain.” I rang George and he said, “I’ve never heard you play, but everybody seems to like you so why not come and see me at [Harrison’s Victorian mansion] Friar Park?” So I did. At that time things were not going well for me and I was driving a Volkswagen Polo. He came out to meet me and said: “You have to drive that?” and we started laughing. He then suggested playing something from [Harrison’s album] Living In The Material World. I had painted a bungalow to that soundtrack, I knew it inside out. We began with Give Me Love and I sang the slide part. When we went on tour, he got me doing the slide to My Sweet Lord. I could never relax until I got past that part. He had a fantastic sense of humour and he was unbelievably easy to be with.

Lemmy

He was the roadie for Hendrix when we were on tour, but I didn’t find that out until later. Many years on, I was at the 100 Club [in London]. He was at the bar, I was at the bar, and we said hello. Lemmy was totally himself and could connect with anyone.

The Invisible Bluesman is out now via The Last Music Company.