This article originally appeared in Metal Hammer #223.

Of all the times to get stuck in traffic, this could possibly be the worst of all. It’s Saturday August 1, 2009, and Anthrax are currently several miles away from Knebworth House, where, in roughly half an hour, they’re due to play a set at Sonisphere. It hasn’t been the best of days. A miscommunication at the band’s hotel meant that their transport never arrived, and the hastily arranged replacement has turned up later than anticipated. But then it hasn’t been the best of months for Anthrax. In fact, even by the standards of a career that’s been defined by stretches of greatness interspersed by periods of chaos and instability, it’s been positively, awesomely fucked up.

Two weeks ago, the New Yorkers were due to play a string of festival dates in Europe, including the UK leg of Sonisphere. The only snag was that their most recent singer, Dan Nelson, never made it onto the plane. The band said he quit via email hours before he was due to join them; Dan countered by claiming he’d been cut adrift by the band. Either way, it left Anthrax with a huge problem: several high-profile dates to play and no singer to play them with.

They were forced to pull the majority of the dates, with one not insignificant exception: Sonisphere.

With no other option, the band called John Bush – their singer between 1992 and 2005 – to ask if he would consider returning for one day, to play Sonisphere. It was a risky move, given that his exit from the band was handled with all the skill of a drunken, one-armed midget trying to juggle chainsaws in the middle of a hurricane. But John, being the gracious gentleman that he is, swiftly accepted his old colleagues’ desperate request.

Right now, on the way to the Sonisphere site, you’d get good odds on betting he’s regretting his decision. In the back of the band’s people carrier, as it literally crawls its way to its destination, tensions aren’t so much high as busting through the sunroof and rocketing towards the exosphere. Whether it’s down to luck, fate, good driving skills or simply a higher power cutting this most beleaguered of bands a much-needed break, Anthrax make it onto the site and to the side of the stage with literally seconds to spare.

As they parade out in front of the 60,000-strong crowd with their stand-in singer, the adrenaline that has been building for the past few weeks finally kicks in. By the end of their 10-song set, Anthrax have served up one of greatest moments of their career. The roar that greets them suggests that it might just have been worth it.

For a band with a penchant for initialised song titles – A.I.R., N.F.L., W.C.F.Y.A. – there’s another all-too-painful acronym that applies to both Anthrax’s Sonisphere experience and their entire 30-year career: S.N.A.F.U.

There’s a track on Anthrax’s new album, Worship Music, that perfectly sums up where we find them in 2011. The song is called Fight ’Em ’Til You Can’t, a title lifted from a line in the 21st century remodelling of Battlestar Galactica. A relentless blast of gut-punch thrash that could have been lifted from one of their 80s albums, it’s ostensibly a song about a world under attack from zombies.

So far, so Anthrax. But there, in the title, is a glaringly obvious metaphor for the band’s dogged approach for the last 30 years.

“On the surface, it’s a fun song,” says linchpin guitarist Scott Ian. “‘Hey, the zombies are coming, we better get our shit together.’ But if you want to talk about buried in metaphor, the deeper meaning to that song is definitely the Anthrax attitude, and my personal attitude: fight ’em ’til you can’t.”

That outlook has never been more important than in the last decade. During that time, Anthrax’s career has effectively been a cycle of heavy metal boom and bust: stretches of determined brilliance followed by moments of malicious circumstance, diabolical luck, inadvertent self-sabotage or sometimes all three at the same time. Not so much make or break as made, broken, then remade. And then broken all over again.But now, two years after narrowly swerving the perfect shitstorm that was their Sonisphere near-miss, things are back to normal in the Anthrax camp. Or at least as normal as it gets when you’re a band who have had 20 different members in the last three decades, and three different singers alone in the eight years since your last album.

Worship Music is Anthrax’s 10th album, and it’s as arse-kicking a celebration of their 30th anniversary as could be hoped for. Heavy without being mindless, thrashy without being retro, it drags everything that made them great back then into the here and now, kits it out in state-of-the-art armour plating, then fits it out with the biggest, most fuck off guns of doom they could order up from www.bigfuckoffgunsofdoom.com. It’s not so much an album as a statement of intent.

It could all have been very different. Worship Music very nearly emerged in a completely different form in 2009. At that point their singer was Dan Nelson, a former personal trainer and ex-frontman of New York sluggers Devilsize and Me, My Enemy, who joined Anthrax in December 2007 to replace Joey Belladonna, who had in turn replaced John Bush in 2005, who had himself replaced Joey back in 1992 (keep up at the back).

The band were sure they had the right guy in Dan. “He’s awesome,” frothed drummer Charlie Benante at the time. “He’s versatile and a metalhead.” From the outside, it looked like a great fit: Dan was a commanding presence during the shows they played in 2008 and 2009 (including an appearance on the HMS Hammer boat on the River Thames before the Metal Hammer Golden Gods). In the spring of 2009, Scott Ian even flew into Britain to play tracks from the album to select journalists.

A few months later, the shit hit the Sonisphere-shaped fan when Dan failed to get on that plane to Europe. John Bush was a gracious short-term solution, but despite clamour from fans and even Scott Ian, he opted not to stick around for the long haul, either not sold on the idea of singing on songs written for another man or simply burnt by past experiences.

Then, in May 2010, something happened that was so forehead-slappingly obvious you wonder why it took them so long to get round to it: Joey Belladonna was announced as Anthrax’s new singer. The Native American head-dress-sporting, leather-lunged belter who was such a crucial part of their sound in the late 80s and early 90s was back for a third ride on the Anthrax merry-go-round, just in time for that summer’s much trumpeted Big 4 shows in Europe.

More than a year later, Joey is still their singer (the line-up is completed by long-term bassist Frank Bello and guitarist/producer Rob Caggiano). It’s Joey’s voice that helps power the re-tooled version of Worship Music, a record that showcases a band who’ve not only survived the sort of trials and self inflicted tribulations that would’ve finished off a lesser outfit, but used their experiences to pump themselves up to the top of their game.

- Slayer: The Making Of Reign In Blood

- Anthrax: How We Made Among The Living

- Gallery: Inside Metallica’s intimate London House Of Vans gig

- Anthrax: Scott Ian's guide to life

“A lot has been said about the making of this record,” says Charlie, a mixture of pride and relief cutting through his broad Bronx accent. “And yes, it’s been very hard. But at some point – and I can’t tell you the day it happened – I saw the light and realised that, finally, it was gonna see the light of day. And believe me, it was a great moment because there was so much negativity. But I’m glad that we persevered. I’m glad that we made it.

Let’s pause here and rewind 30 years for a recap of Anthrax’s career to date. Given the endless twists and turns that have brought them to this point, you may want to take notes (and given previous form, bear in mind there’s a possibility that it could all change again by this time next week).

Scott Ian formed Anthrax in Queens, New York in July 1981 with friend and fellow metal fan Danny Lilker, formerly bassist with local heroes White Heat. The pair christened their new venture Anthrax, after the name of a disease Danny came across during his science class (the monicker would come back to bite them on the arse 20 years later, during a post-9⁄11 anthrax scare).

The band’s earliest musical ventures were shaped as much by Judas Priest and Thin Lizzy as they were Venom, but the influence of New York’s nascent hardcore scene gradually filtered into their sound. The result was a beta version of thrash metal.

“When we first started doing this kind of music, it was new,” says Scott. “A lot of people who were into heavy metal were like, ‘What the hell?!?’. It took people a little while to absorb it.”

By the time Anthrax recruited singer Neil Turbin and drummer Charlie, a scene was taking shape.

In April 1983, a bunch of like-minded Californian upstarts named Metallica travelled to New York to record a demo. “They moved into the Music Building in Queens, which was this shitty squat that someone had turned into crappy rehearsal rooms,” recalls Scott. “Metallica had their own room, which they were living in. We gave them a refrigerator and a toaster and let them come and shower at our house.”

Anthrax’s debut album, Fistful Of Metal, was released in January 1984, six months after Metallica’s Kill ’Em All and a month after Slayer’s Show No Mercy. Housed in a sleeve featuring a frankly ludicrous, not to mention physically implausible illustration of a chainmailed fist bursting out of a man’s face from the inside, the album wasn’t quite the explosion of rage and muscle it could have been.

“When Neil was the singer, it was very much his band,” says the guitarist. “The way he saw Anthrax, the way he wanted us to look and to dress, was very much Judas Priest. We all loved Judas Priest, but our attitude was, ‘There was already a Judas Priest. Why would we want to be another?’.”

Unhappy with Neil’s dictatorial control of the band, Scott and Charlie fired him in August 1984. His replacement was Matt Fallon, former frontman with Steel Fortune (and future singer in an early incarnation of Skid Row). Matt lasted a matter of weeks before departing, though not before starting – but not finishing – Anthrax’s second album, Spreading The Disease.

The man parachuted in to mop up the mess left behind was Joey Belladonna. A drummer-turned-singer from upstate New York, he was tasked with re-recording the vocals on a set of songs written for another man – not for the last time.

Joey would prove to be the making of Anthrax. In the chaos and acrimony that would follow over the next 25 years, it’s easy to forget that he gave them a voice, literally. Unlike many of his peers, Joey could actually sing – something that set Anthrax apart from the competition.

With their new frontman in place, the band quickly muscled to the front of the thrash metal pack. Albums such as Spreading The Disease and Among The Living, and songs such as the Judge Dredd-referencing I Am The Law, became key staging posts in the development of the genre. The New Yorkers were held up as charter members of the Big 4 alongside Metallica, Slayer and Megadeth – that quartet of bands who shaped the sound of thrash metal and turned it into a true cultural force.

Where their Big 4 running mates bristled with a genuine don’t-fuck-with-us menace, Anthrax were happy to play thrash metal’s class clowns, complete with big shorts, knockabout hip hop tributes (I’m The Man) and their own band in-joke (“Not!”) and attendant mascot (the Not-Man).

But the alliance between Joey Belladonna and the rest of the band always seemed an uneasy one. Following the success of 1990’s Persistence Of Time, which toned down their thrash metal roots a good year before Metallica did the same with The Black Album, the wheels came off the wagon. In hindsight, the catalyst was Bring The Noise, their successful 1991 collaboration with Public Enemy. There was no place for Joey Belladonna on the song; shortly afterwards, the band decided there was no place for him in their future. In 1992, he was fired and replaced with John Bush.

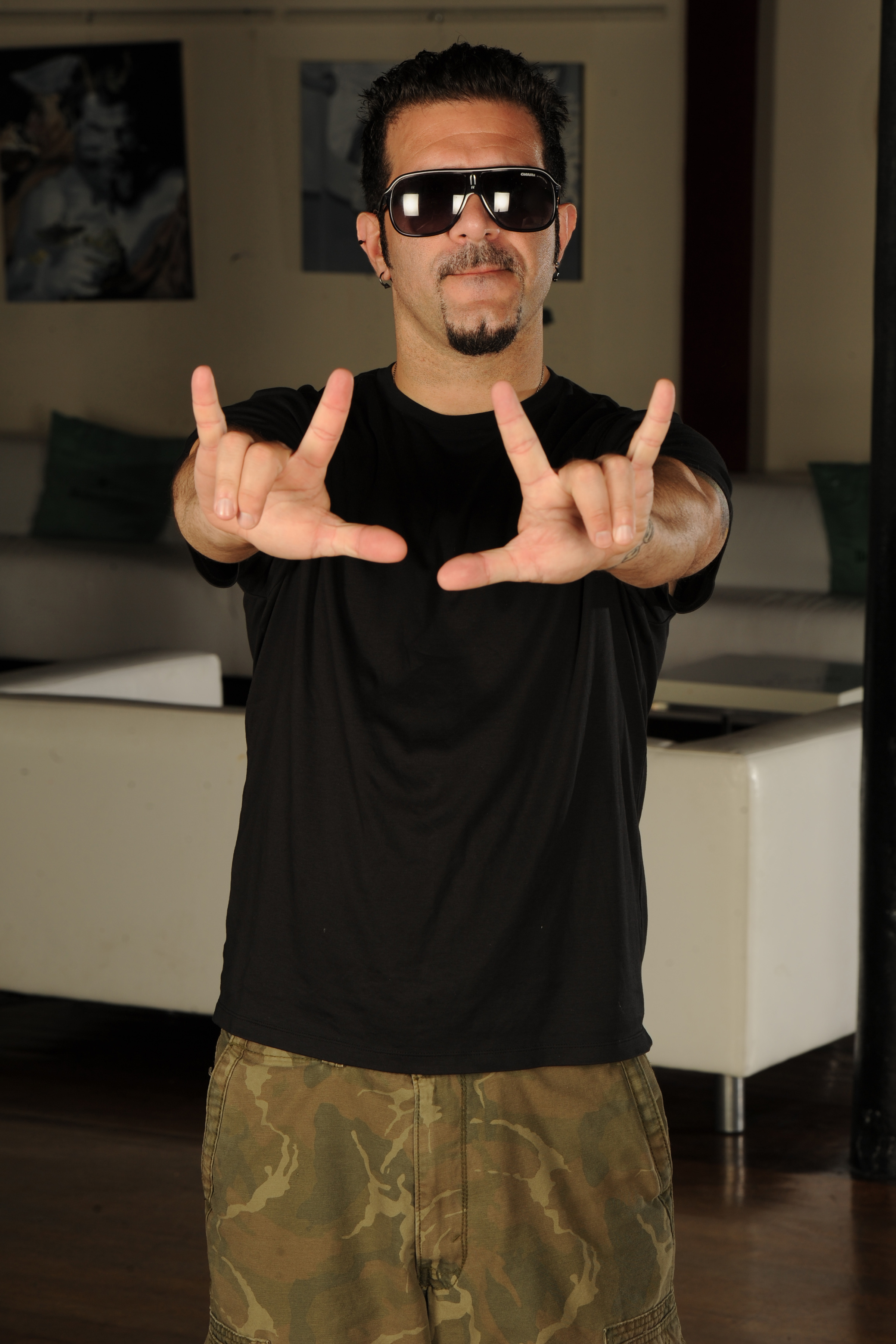

Not for the first time, and certainly not for the last, Anthrax had a new singer. Scott Ian Rosenfeld has been the guitarist, mouthpiece and sole constant in Anthrax throughout their 30-year career. Despite having gone through much that would have finished off lesser mortals, his passion for the band he started remains undimmed. Ask him if he’s ever considered quitting, and his answer is emphatic.

“Things have been hard at times, but I’ve never got to the point where I’ve said to myself, ‘I’m done, I can’t deal with this any more’,” he says. “I’ve certainly occupied my time with other things when Anthrax has had down time, when we’ve wanted to get out and work and we couldn’t because it was like the universe conspired against us. But I’ve never thought about walking away.”

The guitarist is one of those rare musicians who will answer any question thrown at him without guile or obfuscation, though not without the odd flash of tetchiness. Today, he’s in upbeat mood, talking about Worship Music with no small amount of pride. In fairness, given the monumental ball-ache that was its creation, he’s got every right do so.

“We started writing the songs for what would become this record back in 2007,” he recalls. “Just the two of us, Charlie and I, sitting in our studio in Chicago [Charlie’s adopted hometown] with a bunch of ideas. After about a week, we had four or five things semi-arranged. It sounded cool. And from that point, we got hold of Frankie and Rob, and said, ‘Hey, it’s time to start working on a record’.”

There was one minor problem: they had no singer. Joey Belladonna had participated in a lucrative 18-month reunion tour that ran through 2005 and 2006, but the two parties had once again parted ways when that finished (albeit, insists the guitarist, in a more amicable way than their previous split).

Enter Dan Nelson. Introduced to the rest of the band by guitarist/producer Rob Caggiano, he seemed the perfect fit. A decade younger than the rest of the band, he was the grease the band needed to get moving again after a sticky few years.

Through 2008 and 2009, snippets of songs were put out on the internet; clips of the band playing live appeared on YouTube.By 2009, Worship Music was finished, and Scott Ian was its biggest cheerleader.

“We loved it,” says the guitarist today. “We felt strongly about it. We said, ‘This record is awesome and we can’t wait for the world to hear it’. And then we had to go find a new singer.”

Exactly what happened in the run-up to their ill-fated trip to Europe is shrouded in confusion. When it happened, Anthrax said Dan was too “ill” to perform. Dan denied this. Anthrax then said he quit. Dan said he was fired. The only thing that stopped it from being a proper soap-opera ding-dong was just how undignified it was.

Today, the rhythm guitarist is sticking by his original story. Or at least the second version of it…

“He quit the band,” says Scott firmly. “I stand by the statement we made in 2009. We received an email from him saying that he’s not doing this any more, he’s not getting on a plane, don’t come to my house, don’t try and talk me out of it, it’s over, I quit.”

DID YOU SEE IT COMING?

“This was the third time he’d pulled this on us. And the previous times, what would happen was that we’d say, ‘Dude, what’s wrong?’. He’d make demands and we would cave in to those demands. We were, like, ‘We can’t lose our singer now, we have a finished record’. He basically held a gun to our head. And [this time] we just decided that we’d had enough of this – we’d rather not be a band than a band who has a gun held to their head. We took his resignation and moved on.”

WHY DO YOU THINK HE QUIT?

“I just think he couldn’t handle it.”

HANDLE WHAT EXACTLY? THE TOURING? THE LIFESTYLE? THE OTHER PEOPLE IN THE BAND?

“Everything. He just couldn’t handle it. He was in over his head.”

HAVE YOU SPOKEN TO HIM SINCE?

“Hell no. The dude left us hanging. It was a complete dick, unprofessional move.”

The guitarist says that for all the line-up instability and general goat-fuckery of recent times, two things have emerged stronger. The first is Worship Music. Several songs were re-recorded and rearranged, among them In The End and Judas Priest; three songs were ditched completely.

The second thing is the entity that is Anthrax itself.

“Look, I’ll be the first to agree that nothing in life is perfect,” he says. “We’ve had to fight for everything this band has ever done. It’s not like a couple of years of hard work were a new thing for us. When things become difficult for us, we just work harder. And yes, we did get a better record for it. You know, fight ’em ’til you can’t.”

If there’s one thing that helped Anthrax through this period, beyond the sheer bloody-minded stubbornness of the native New Yorker, it’s the fact that even then they were no strangers to adversity.

The idea of the ‘Big 4’ isn’t strictly accurate. Judged by record sales alone, ‘Metallica And The Little Three’ is closer to the truth. Even at their height in the 80s, Anthrax always existed in their old friends’ shadow, commercially if not artistically. Go past The Black Album or Master Of Puppets, and there’s a big drop-off before you hit anything with Anthrax’s name on it (or Megadeth’s or Slayer’s, in fairness).

The closest Anthrax came to proper crossover success was with their landmark cover of Public Enemy’s Bring The Noise. Growing up in Queens and The Bronx, those twin cradles of hip hop, they’d already dabbled with rap-rock in the shape of I’m The Man, the B-side to 1987 single I Am The Law. But Bring The Noise was something else entirely: a genuinely genre-busting mashup of the best bits of metal and hip hop, created by the leading lights from both fields and touched by streetwise genius.

Released just before Nirvana ushered in the great grunge goldrush, it briefly put the Anthrax name on everybody’s lips. It also marked the point where they parted company, musically and physically, with Joey Belladonna.

“Bring The Noise brought us to a different audience,” says Charlie Benante. “Maybe if we’d done a whole album of songs like that, then we’d have been in a different position.”

They didn’t, though that decision appeared not to harm them, at least initially. The band’s next album, 1993’s The Sound Of White Noise, dialled the old-school thrashings right down in favour of a muscular, forward-looking sound. With former Armored Saint powerhouse John Bush behind the mic and a hurricane strength tailwind provided by the success of Metallica’s Black Album behind the band, the album sailed past the platinum mark in the US. More crucially, with John, they’d successful reinvented themselves as a contemporary metal band.

But that album would prove to be a watershed for Anthrax. Two years later, they released Stomp 442, their second John Bush-fronted album. Produced by voguish studio team The Butcher Brothers and featuring the first of three consecutive guest appearances on an Anthrax album by Pantera guitarist Dimebag Darrell (In The End, the epic centrepiece of Worship Music, is a tribute to both Dimebag and Ronnie James Dio), Stomp 442 took off like a million dollars and crash-landed like 10 bucks. The grunge party was in full swing, and there was no room for a band doing what Anthrax were doing. Their label, Elektra, dropped them, and they slunk back to New York, battered but not defeated.

Their next album, 1998’s Volume 8: The Threat Is Real, fared even worse and it would be five long years before they released another studio album. That record was We’ve Come For You All, and whether down to adversity or experience or some alchemical combination of the two, it turned out to be the best work of their career.

Striking the perfect balance between the relentless energy of their past and the melodic muscle of the present, it was a world-beater in waiting. The Who’s Roger Daltrey popped up to add backing vocals to Taking The Music Back; a fresh-from The-Matrix Keanu Reeves provided some proper A-list Hollywood star quality in the video for Safe Home.

It should have been huge. But it sank without trace. And then Anthrax went and really ballsed it up. They reunited with Joey Belladonna.

If Scott Ian is Anthrax’s Gene Simmons – garrulous, outgoing, the public face of the band – then Charlie Benante is their Paul Stanley: a man whose lower public profile masks the fact that Anthrax couldn’t exist without him.

The drummer joined the band in 1983, not long before they started work on Fistful Of Metal. Today, he’s relocated to Chicago with his wife and family, though he remains the band’s chief songwriter, as well as its joint senior partner.

When it became apparent that the line-up that took part in the 2005⁄2006 reunion tour wasn’t going to stay together, Charlie took a few months off to take a break and generally clear his head. When he did start writing for the next album, he found himself in a peculiar position: namely, that his band didn’t have a singer.

“I just started writing songs with Joey’s voice in my mind, and even with John’s voice in my mind,” he says. “I contacted the other guys and said, ‘Here’s what I got’. Then we started bouncing ideas off each other.”

Where Scott Ian is talkative and open, Charlie is more guarded. He refuses to be drawn on the specifics of why Dan Nelson quit, stating that the situation is still in litigation. Tellingly, he never refers to Dan by name – to Charlie, he is simply “the singer at the time”.

During the chaos of the last few years, Scott Ian found an outlet for his frustrations and his creative urges in The Damned Things, the supergroup he founded with fellow Anthrax guitarist Rob Caggiano and assorted members of Fall Out Boy and Every Time I Die. By contrast, the only extracurricular gig Charlie got involved in was a project to create a Mickey Mouse figure for Disney (“It was a Mickey Mouse mummy,” he says with no small hint of pride. “They loved it”). But if the drummer was irked at being left to hold the fort alone, he doesn’t show it.

“After that whole thing went down, other people needed to get away from it for a bit,” Charlie explains. “That’s fine – that’s just what they wanted to do, to clear their heads and come back to the whole Anthrax thing with a clear mind. I was still here, minding the store. I wasn’t focused on anything but this.”

WHAT WAS THE LOW POINT OF THE LAST FOUR YEARS?

“There wasn’t a low point in terms of making the record you actually hear. That was all high. There were low points way before that, when we were about to go to Europe and we got the call that the singer at the time was not going, that he was leaving. That was a very, very low point for all of us. In the history of the band, we’ve never had to deal with anything like that. We’d never, ever pull that bullshit.”

WHAT WAS THE MOOD IN THE BAND LIKE AFTER DAN NELSON QUIT?

“It went through different stages. At first we were very angry. Then we were very depressed, ’cos we felt let down and we felt we’d let the people down.”

WHY DIDN’T JOHN BUSH COME BACK AFTER SONISPHERE?

“John was never gonna be in the band. We just knew he wasn’t gonna be a part of it. When the Big 4 thing came up, there was only one person who deserved to do it, and that was Joey.”

WHO CALLED JOEY AND ASKED HIM IF HE WANTED TO COME BACK?

“I did. I was talking to Joey prior to this, because I had some material that didn’t really fit Anthrax - the music wasn’t very aggressive. It was for a side-project I wanted to do with different singers. Joey was one of the people I thought of. I sent it to him, and that opened the lines of communication.”

WHAT DO YOU THINK PEOPLE THOUGHT WHEN THEY SAW WHAT WAS HAPPENING IN ANTHRAX OVER THE LAST FEW YEARS?

“I think they looked at us when this whole thing was going down and thought: ‘Why can’t they just keep it together?’ I for one thought the same thing. But if they only knew how hard it was to keep it together, they’d probably have a better understanding.”

WHY DIDN’T ANTHRAX JUST KEEP JOEY ON AFTER THE REUNION TOUR?

“The band didn’t remain the band after the reunion because of… basically, management at the time, which no one felt comfortable with, which is why we left. When that whole thing went down, it didn’t hold the band together.”

If anything sums up Anthrax’s capacity for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, it’s the 18-month reunion tour that saw them reuniting with both Joey Belladonna and former guitarist Dan Spitz, a fellow victim of the thrash wars.

On the surface, it seemed like a smart move. For a certain generation of thrashheads, the Belladonna/Ian/Spitz/Bello/Benante line-up was the definitive incarnation of Anthrax. Sharon Osbourne obviously thought so – in 2005, she offered the band an undisclosed sum of money to play the Ozzfest, reportedly on one condition: that the band appearing on the Ozzfest stage was the ‘classic’ 80s line-up.There was a screamingly obvious problem here, and its name was John Bush.

Just two years earlier, John had been a crucial part of the line-up that had pulled a genuine masterpiece out of their collective arses in the shape of We’ve Come For You All. And now he was being asked to step aside in favour of the guy he replaced.

The situation put Anthrax on the (devil) horns of a dilemma: rake in a huge pay day but cut loose the man who had been part of their greatest creative peaks, or ignore the offer and face the very serious and likely possibility of extinction.

In fairness, they tried to compromise, asking John if he’d do the tour alongside Joey. There was a precedent for this in the shape of Ball Of Confusion, a cover of The Temptations’ soul classic recorded for 1999’s Return Of The Killer A’s compilation that featured vocal sparring between John and Joey. But this time, John Bush was having none of it.

“They asked me to do it and it just wasn’t right for me,” he explained in 2007, with the sort of good grace that would have put Mahatma Gandhi to shame. “If they felt they had to do that, I understand. It wasn’t like I was going, ‘Yeah, do it. That’s great’. But once it happened, I was like, ‘OK’. It was like a book ended. It’s much better to look at it that way than to be angry or frustrated, ’cause I really don’t feel that way.”

And so the decision was made for them. Over the next 18 months, the resurrected 80s version of Anthrax played gigs around the world. The shows were terrific, but there was an uneasy sense of nostalgia about the whole thing, not to mention the lingering suspicion that they’d just shafted their last singer.

Worse, offstage the old tensions that saw Joey evicted in the first place hadn’t gone away. Sources recall the band splitting into two camps: Scott, Charlie and Frank in one; an increasingly miserable Joey and Dan Spitz in the other.

“The reunion tour, for me, was done for and generally clear his head. When he did all the wrong reasons,” admits Charlie Benante now. “It was, like, ‘Hey, you’re gonna reunite and go out on tour and repair all your relationship’. Fuck, it was just wrong.”

Wrong, certainly, but also disastrous for Anthrax in terms of the chain of events it set in motion.

“We finished the reunion tour with Joey Belladonna and Dan Spitz in October 06, and actually for the first time in the history of the band, made a conscious decision to take a break,” says Scott. “At that point, Charlie, Frankie and I had been on the same write-a-record-release-a-record tour cycle since Spreading The Disease. There was never a break. We were, like, ‘We’re shutting this shit down for months and then we’re gonna get together and start writing’. Really, that’s as far as we were thinking at that point.”

With hindsight, it’s probably just as well they didn’t give the future much thought. If they knew what the next few years would hold, they may well have thought Of all the musicians who have passed through Anthrax’s ranks in the last 30 years, it’s hard not to feel sorriest for Joey Belladonna. John Bush may have been on the receiving end of a questionable business decision when the Among The Living line-up reformed, but at least he had the option of ducking out of the sorry saga.

But Joey Belladonna hasn’t had a lot of say in the matter. When he first parted ways with the band in the early 90s, it was their decision not his. Nearly 20 years on, he still sounds mildly baffled by his original dismissal.

“I think they could have left it alone,” he says. “If you want to debate that my voice wasn’t set for what they were looking for, I wasn’t that far off. We still would have been a great band with some great songs, and still found our way through all that 90s stuff. I didn’t hear anything that happened after I left where I went, ‘Oh my god, they finally figured it out, they’re a great band now’. But that’s neither here nor there now.”

Even during his original tenure in the band, Joey was a square peg in the round hole of Anthrax. Where his band mates loved Judas Priest and Iron Maiden, his favourite band was Journey. Where the rest of them wore Public Enemy T-shirts and shaved ‘Not’ into their chest, he came onstage in Bermuda shorts and an Indian head-dress.

Despite the impeccably great music they made together, it was sometimes hard to shake the sense that he was the right singer in the wrong band – and that they all struggled to get along as a result.

“I don’t know why,” he says dolefully now. “Some people have a little bit of front – ‘You couldn’t know as much as I know’, or ‘You’re not as in the business as I am’. Somehow, there was this plateau of priority of knowledge and connection. It’s about being a good, hard-working band. You can’t push aside each other, as if I couldn’t help.”

This is very much how Joey talks: 85 miles per hour, non-stop, always friendly but not always coherently (what exactly is a “plateau of priority”?) But while he’s not as media-savvy as Scott Ian or Charlie Benante, there’s an endearing openness to him – a willingness to voice his frustrations about past problems and his place in the scheme of things (which, looking back, may have been one of the things that landed him in trouble with the rest of Anthrax in the first place).

When it came to recording his parts for the new album, Joey found himself in a peculiar situation. “Me and Jay [Rustin, the producer who oversaw his vocal parts] were alone the whole sessions,” he says. “We would finish three or four songs, then come back a few weeks later and do another three or four songs. When I emailed the songs to them, I’d say ‘Hope you like it’ and move forward instead of keep putting a roadblock up, saying, ‘No, that’s wrong’, or ‘I don’t like it’.”

HOW DID IT FEEL SINGING SONGS WRITTEN FOR ANOTHER GUY TO SING?

“I didn’t consider it. Hell, I came in on Spreading The Disease. They had some guy in there who didn’t last for maybe a week or so. All’s I did was like I’d do for anything else. Everything was really well structured. I didn’t get too far into taking things apart. I came up with a lot of melody stuff, a lot of harmonies. I didn’t hear all the cuts a lot of time. I was going at it bone dry.”

DID THAT FEEL WEIRD?

“That was my favourite part. They really left me be. You’re not looking through the glass and seeing these guys yakking. You’re not wondering, ‘Are they mad or indecisive, or is it all good?’.”

WHY DIDN’T YOU STAY ON AFTER THE REUNION ENDED IN 2006?

“The reunion was great. They said, ‘We wondered if you wanted to go out and play and give the fans some music’. I was like, ‘Yeah, sure, that sounds great’. But it didn’t feel like anyone wanted to give [me] a chance to be in the band. Nobody ever gave me that complete open door, like as if it was baby steps. And then you find out online that they got some guy no one even knows, and they expect it to fly… I get baffled by that.”

WHAT DID YOU THINK AS YOU WATCHED THE WHOLE ANTHRAX SOAP OPERA SLOWLY UNFOLD?

“You mean when they got the new guy? I took a quick peek at it on a YouTube thing – like, a 17-second demo of a new song. I was like, ‘Oh my god, this ain’t good’. I didn’t dig it at all. It went away real fast. That was a bit of an indication.”

DID YOU EVER THINK, ‘WHY NOT JUST CALL ME?!’

“Yeah, kind of. I was still doing Anthrax stuff. I was in the biggest training school for Anthrax, waiting to go. I wasn’t dwelling on it, but I wasn’t far from being in it in a second.”

SO WHO CALLED WHO?

“The sequence of it was: new guy goes, John doesn’t wanna do it, so who do they call? Management said, ‘Get him on the phone’. Personally, I don’t even think it came from the band. I hate to say it, but I don’t think they were thinking of me. That’s sad too. But Charlie said, ‘Management want to speak to you’. I figured that this [current reunion] would be what it was. And sure enough…”

DO YOU HANG OUT TOGETHER?

“We don’t hang out. There is no hanging out. You are lucky if you get CC’d on emails. That’s a big moment – ‘I just got an email!’. I don’t want to dwell on that, but every day I go, ‘What the fuck?’. I still think, ‘Are we cool right now?’. Even with people digging the new record, I’m like, ‘Are you sure? I don’t know what else I can do to make you think that I’m alright.’.”

ARE YOU HAVING FUN IN ANTHRAX AT THE MOMENT?

“Oh yeah, I am making it as much fun as I can make it. I can’t pull a rabbit out of anybody’s hat. You have to be positive. If we’re gonna do this, that’s the only way you can do it. Otherwise it’s gonna be like a stale piece of bread.”

And so here Anthrax are in 2011, 30 years into a career that most other bands would give their left arm to have and their right arm to avoid. They’re sitting on one of the best set of songs they’ve ever put their name to, yet the alliance with the man who sings with them still sounds like it hasn’t been completely worked through. You have to wonder if they look at their Big 4 compadres Slayer and think: “I wish we had their stability”?

“We’re not the same animal,” says Scott firmly. “On paper, if those five we started the band with could still be Anthrax, that would be awesome. But it never would’ve worked. Decisions we’ve had to make to keep the band moving forward are the things that kept the band moving forward. There are times when the band would have not been a band any more if certain decisions weren’t made.”

But there are two things that ensure that Anthrax will be fine for the next few years. First is the fact that Worship Music is a fine record – arguably the finest record of the last decade by any of the Big 4 cabal, up to and including Metallica. Second: they simply can’t afford to fuck it up again, or they’re done. And they know it.

“We’ve had solidarity for a while,” says Charlie. “I think people are starting to feel comfortable. Like, ‘OK, now I’m behind them’.”

WILL JOEY BELLADONNA BE THE SINGER ON THE NEXT ANTHRAX ALBUM?

Charlie: “Absolutely. One hundred per cent. There’s no talk of anything else. As a matter of fact, the songs that were left over from this record are as good as anything on the record – three or four songs. that could be the start of the next one. But let’s enjoy this one first, let’s live in the moment.

DO YOU THINK ANTHRAX HAVE HAD THEIR DUES?

Scott: “Absolutely. I can’t complain. I still get to be in this band 30 years later. Something’s obviously gone right all these years. Do I wish some records would have had more attention paid to them? Of course I do. Do I wish we’d had a little bit of Metallica’s success? Are you fucking crazy?! Any dude in any band, with the exception of Ian Mackaye from Fugazi, is lying if they tell you they don’t want a piece of that. But ask me if we’ve had the respect we deserve from the metal world, and yes. We’ve certainly had that.”

ASK THEM IF IT WAS WORTH IT, THE PAIN AND UPSET AND HEARTACHE OF THE LAST FOUR YEARS – OR EVEN THE LAST 30 YEARS – AND THE ANSWER IS EMPHATIC.

Scott: “I wouldn’t change a thing. If I had a time machine and I could go back and change something, then maybe I wouldn’t be standing here with the best album of our fucking career. To quote The Beatles, it’s a fucking long and winding road. But as far as being able to finish this record, at least wegot to the end of it.”

Adds Charlie with no less conviction: “Yeah, it was worth it. This is not anything fake that we’ve fabricated and made a song about it. These are songs we’ve lived. All the blood sweat and tears that we lived went into this record. This is the truth.”