“Uzis for Christmas? There coulda been.”

Alan Niven, Guns N’ Roses’ original manager, is thinking back to December 1992 when, rumour has it, he gave a member of the GN’R entourage three enormous wooden boxes for Christmas. Imagine the guy’s yuletide joy when he cracked open the boxes on Xmas morning to find that in one was a very deadly (and very illegal) Uzi sub-machine-gun, while the other two were rammed with rounds of ammo. Deck the halls with bows of holly, motherfucker.

“I know that sounds demented to a European sensibility,” says Niven, “but then you didn’t live through the LA riots. Let me tell you, it was a moment of pure social breakdown and lawlessness. The first arson fires were lit on a Thursday night, and the National Guard arrived Monday morning – without ammo, as it happened. In the meantime the LA cops were nowhere to be seen. We were on our own – and on top of that there were rumours that cop uniforms had been stolen from dry-cleaning businesses, that National Guard armouries had been broken into by the rioters…”

When three LAPD officers were acquitted on April 29 that year of using excessive force during the arrest of one Rodney King – despite footage clearly showing a group of cops beating a man no longer able to put up any resistance – the people of Los Angeles displayed a genuine appetite for destruction: looting, burning and battering anything and anyone in their path. Fifty-three people died in six days of rioting: gunned down by the police, shot by storekeepers protecting their properties, burned alive, beaten, or the victims of random drive-by shootings.

Niven had been fired as GN’R manager the year before, but “when the riot went down, Iz [Izzy Stradlin] was over to my place in a heartbeat for a brown bag containing my .357 Magnum and beaucoup ammo. After the riot I bought him a gas-powered 12-gauge shotgun used by the LA SWAT teams. That’s a serious piece of ordinance. I took him to the gun club to teach him how to use it. The target basically dissolves in a rapid-fire hail of slugs. I ask him: ‘Feel safer now?’ ‘Yeah Niv,’ he says, with a big grin on his face.

“After all that I even got hold of Kevlar [bullet- proof] vests for my family, and arranged for an Arizona helicopter company, at huge expense, to pick up the wife and kids should another riot occur.

“It wasn’t Welcome To Disneyland,” says Niven. “It was Welcome To The fuckin’ Jungle.”

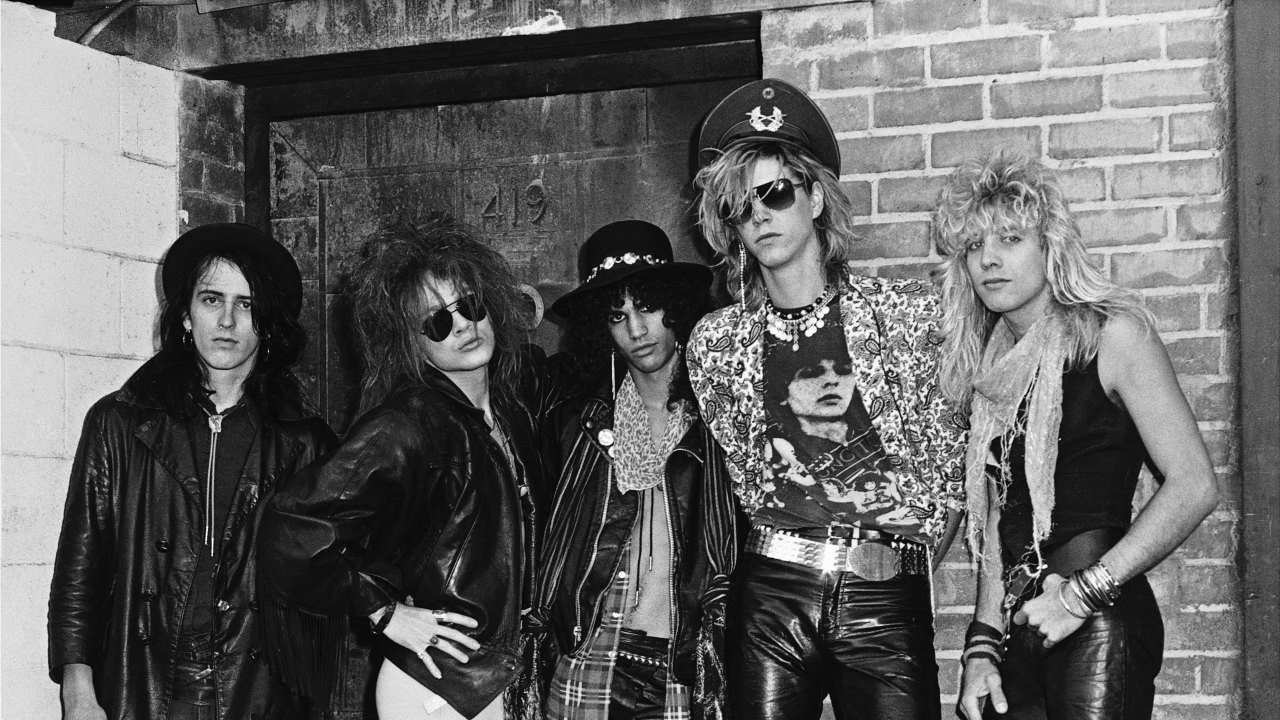

Alan Niven is the forgotten man of the Guns N’ Roses saga. Izzy Stradlin once described him as “the sixth silent member” of GN’R, but he refused most interview requests during his tenure with the band (from 1986-1991), and has done few subsequently (“I recently did an interview for Fuse TV, something I will not be doing again any time soon,” he says. “I’ve rarely ever talked on the record – I thought the music ought to be eloquent enough”). Instead he lives in Arizona, an Englishman abroad, where he keeps his hand in with Tru-B-Dor, a production company he runs with his partner Heather, which helps new bands and musicians. He also continues to write songs – Rick and John Brewster of Australian band The Angels have released three albums’ worth of his material. While this may be unusual for a manager, it’s nothing new to renaissance man Niven: he was, after all, the main co-writer for Great White, who he also produced and managed – something that’s still a bone of contention in GN’R circles.

Both bands sold their millionth record on the same day – April 7, 1988 (coincidentally, Niven’s birthday) – and the combined pressures and betrayals that came with managing two bands that broke at the same time were immense. “Pressure?” he says. “Let me put it to you this way. When the relationships ended, I retreated to the desert. To the mountains of Arizona and a house five miles down a dirt road, 25 miles north of nowhere. We made our own solar electricity, pumped our own water from two wells. I couldn’t get far enough away from LA, the betrayals and all the negative crap.”

But managing two bands, however different, was an advantage at first. Niven talks of how, famously, the Welcome To The Jungle video that broke GN’R in the US only happened because it was piggybacked on to a shoot for a Great White video. He talks of the support slots Great White got them, and how, when GN’R went stratospheric, Great White graciously and wisely gave up closing slots to Guns (“Better to be a hard act to follow than to follow a hard act and all that,” he says).

Under Niven’s management GN’R went from being unmanageable train-wrecks to being one of the decade’s most iconic bands, with the biggest- selling debut album of all time in Appetite For Destruction. He coulda been lucky. On the other hand, it could easily be argued that after his departure Guns N’ Roses rarely put a foot right – releasing the overblown Use Your Illusion albums, before disintegrating into the epic saga of sackings, back-stabbings, rampant egoism, missed deadlines and blown budgets that eventually produced Chinese Democracy. Whatever the truth, it’s unlikely that Axl Rose will be inviting Niven round for barbecue and beers any time soon.

Days before Christmas, on December 11, 2008, Axl went on two GN’R websites and posted his take on life, the universe and everything. Having refused all interview requests to help promote the album he and his guitar army had spent 15 years making, Rose went postal online instead. It could be seen as admirable: he went straight to his fans, answering their questions and bypassing the media he claims to hate so much. On the other hand, it gave him freedom to rant without fear of contradiction, stirring up a hornet’s nest as he did so, with accusations about Slash, Brian May, the media, and his first manager, Alan Niven. In particular – and in an effort to explain an old accusation made by Slash that Axl had strong- armed him and Duff into signing over ownership of the GN’R name to him – Axl claimed that, on the contrary, “when Guns renegotiated our contract with Geffen, I had the bit about the name added in as protection for myself as I had come up with the name and then originally started the band with it. It had more to do with management than the band, as our then manager was always tryin’ to convince someone they should fire me. “As I had stopped speaking with him he sensed his days were numbered and was bending any ear he could along with attempting to sell our renegotiation out for a personal pay day from Geffen.”

Niven refutes the allegations completely, and puts his side across in this interview. “Good ol’ Axl,” he says drily. “No one ever did anything good for him. We all fucked his life up, right?”

In the words of Rolling Stone, Alan Niven was “a tough, brainy Englishman” who had worked for Virgin and moved to LA to join indie record company Greenworld where he helped sign Mötley Crüe. By 1982 he was running Enigma Records, friends with Don Dokken, and manager of up-and-coming blues-rockers Great White. Back then, one of Niven’s favoured ‘getting to know you’s was to invite a new friend over for dinner and, unbeknown to his guest, cook them “one of my specialities – roast chicken à la LSD – for a little after-dinner surprise headrush”.

He was, it could be said, a little bit rock’n’roll. Exactly the type of guy you might turn to if you had an unruly rock band that had been turned down by all the major management companies in town.

Tom Zutaut – a friend of Niven’s since they’d worked out the agreement that took Mötley Crüe from Greenworld to Elektra records – was in just that predicament. By 1986 Zutaut had left Elektra to work in the A&R department at Geffen. Having signed GN’R to the label, he went looking for management. “But because they were notoriously and seriously fucked up – and had a reputation for being unprofessional hellions – no one wanted to get involved,” says Niven. “No one wanted to invest their time and money into a bunch of addicts and destructive assholes who would probably self-destruct as a band, overdose, or piss off the record company who would then exact revenge and end their career.

“Tom had been to all the big-time management firms and had been turned down. Bernstein and Mensch. Tim Collins. Rod Stewart’s management gave it a go but were failing and bailing. Tom actually asked me on three separate occasions to meet the band but I was sceptical.”

He was also busy. Great White had been signed and then dropped by EMI-USA after a bidding war in 1983. Now they were unsigned, and all of the previously rejected labels were pissed off and didn’t want to know. Niven funded and recorded a Great White album under his own steam, got it played on the radio and then got the band re-signed to Capitol/EMI.

“It had taken a year-and-a-half to get back in the saddle. I wasn’t about to let this situation get fucked up by spreading myself too thin. I was just a one-man operation; no offices, no secretary, no receptionist, no go-fers, no limos. I also had a pregnant wife. So I said no to Tom twice.”

Eventually, to help a friend, Niven agreed to check GN’R out. “So I went to see them at the Troubadour, and there was Axl running around in a fuckin’ kilt with big, 80s hair,” he says. “On the other hand, Izzy just oozed this Keef-like cool and played great synchopated rhythm parts. He and Duff on their side of the stage held the whole thing together and their attitude had an irresistible Stonesy groove about it.

“Tom gave me a demo tape and you could hear that Slash could play. In fact I still love some of his playing on that cassette. And Axl had that voice: totally distinct – like Ethel Merman on helium. They weren’t going to be a Journey or a Def Leppard, that was for sure. And I wasn’t sure how radio would take to them, if at all. They were far too fuckin’ raw – Great White were considered ‘edgy’ in those days. But it was a real band, and I figured that if they could be held together, made functionally professional, and if I could get them to tour, then maybe they could make a mark as an underground band. Maybe even get to gold status in sales and build from there. If anyone says they knew then that this band were going to be as huge as they became, they are either certifiable or a liar.”

It wasn’t all selfless, naturally. “From a calculating, professional perspective, I knew that the situation was so fucked up I couldn’t be blamed for making it worse, and if I got something done with them then I would have further proven my chops. And I figured I had a decent shot: I had the power of an English accent, and I wasn’t a typical Hollyweird manager. I just had to get through to the band.”

To that end, he went to visit them at the house they were sharing in the Hollywood Hills. “There was a smashed toilet lying in the drive,” says Niven. “Some stripper I vaguely knew from the Sunset scene was coming out the front door – and only Iz and Slash had turned up for the meeting.

“So we sit at the dining table and Iz proceeds to nod out – loaded! See ya! Slash says: ‘Come on, I gotta show you something,’ and lurches off into his bedroom. In the corner is this glass case that has this huge snake in it. Now, I have this ungodly fear of snakes – I cannot stand the fuckers – so it seems like it takes up the whole side of the room. Slash suddenly produces this cute little white rabbit and drops it into the tank. The snake suddenly springs to life and swallows this fur ball whole. Inside I am just losing it but I stay cool. I think I passed the initial Iz and Slash tests right there: I didn’t freak out on either of them.”

There were more tests to come. His relationship with Axl Rose was frosty from the off (“The first time I met him he was aloof, reserved and somewhat formal. He gave off this suspicious and superior vibe”). As if to register his disapproval, Axl didn’t turn up for their first gig with Niven as manager.

“Axl was unreliable from the very first show,” he says. “He failed to show up for this one-off gig with Alice Cooper in Santa Barbara, so I made the band go on without him. It was horrendous. I’m standing in the audience hearing all these people mutter about how they sucked, that they had heard they were a buzz band in LA. And Iz and Duff are just choking on the vocals. It was dire.”

How did Axl take the fact that they played without him?

“Oh, I don’t know. There was some sort of boo-hoo and a convoluted excuse. The usual. [The Here Today Gone To Hell website, which in recent years has become Axl’s mouthpiece, claims that Axl wasn’t on the guest list and couldn’t get in.] But really, either you are there for your mates, or you’re not. He claimed to have turned up just after they went on. But we didn’t see him. There was always a boo-hoo and a convoluted excuse.

“But the rest of the band won my heart and respect for doing that. I was prepared to do anything for them at that point. I told the band then that if they decided to find another, more reliable singer – and even if they lost their deal as a consequence – I would hang in with them. Whatever Axl says or thinks, I did not and never said: ‘Fire Axl’. And there were bodies and major problems all over the place before they sold records – before Appetite… was even released. Others would have run for their lives. I was in for the long haul – for good or bad.”

His commitment was certainly greater than Geffen Records’, who told him he had three months to turn things around. “But if Geffen had dropped the band I would have stayed with it, just like I did with Great White,” says Niven.

One of the greatest scams dreamed up by Niven and Zutaut was the Live ?!*@ Like A Suicide EP, financed by Geffen but released on the fictional Uzi Suicide label to give the band some indie credibility.

“I had done two indie records with Great White, one with Mötley and one with Berlin,” says Niven, “and all of them worked: they got good press, cred, and set up the major-label release. I wanted to do the same sort of set-up for GN’R, even though they were already signed. But most importantly I wanted to get them to London as soon as possible. Breaking in England first, and in the UK press, was the way to accelerate their status. And I knew England would love ’em. I had seen Hendrix, the Pretenders and others break in the UK press before they made it in America, and I knew this was the way to go for the Gunners.”

The plan: release the EP, flog ’em to a wholesaler, get alternative/indie cred, and then use the money to come to London. Amazingly, Eddie Rosenblatt, President of Geffen Records, went along with it. “And he allowed me to drive up in a van and collect the whole print run, and go sell ’em to Important Records. He said to me later: ‘I rather wondered if I would see you again!’ But I was back with a cheque for over $40,000 the next day, and the UK trip was on.”

The UK fell hard. In June 87 the band’s three shows attracted sensationalist headlines in the tabloids and fevered write-ups from the music press. Not that their UK record company were impressed. “The attitude at WEA UK sucked. It was basically: ‘Make yourselves a hit in America, and then we might look at you’. The then CEO of WEA UK did actually come down to one of the Marquee shows, which he did not support, and pompously introduced himself: ‘I’m so-and-so and I run WEA UK’. “I just looked at him. ‘They have my commiserations,’ I told him.”Once they got rolling, GN’R were unstoppable.” By the time they played Donington in 88 they had sold more tickets in England than WEA had sold copies of Appetite… And as country after country fell for the band, the pressure changed. Now Niven was being button-holed by David Geffen wondering when he could expect the next record. “This is a guy who sued Neil Young because he didn’t deliver David’s idea of a hit,” says Niven. “The commerce generated by the follow-up proper to Appetite… was expected to generate more than $100,000,000 in the first week.

“Do you think he’d have any compunction about having me undermined and replaced if he didn’t believe that I was the best person to hold this band together and deliver?”

Fame, money and power drove the band apart, says Niven. “Axl wanted to take control. Slash no longer had a drug problem – he could afford them. Izzy wanted to find his missing million dollars. The missing million, by the way, was not missing, it was in an escrow account. It was to be released when Guns booked a tour of a certain size, or had recouped the other $1.5 million they had already received as an advance against merchandise sales. Try explaining that to a paranoid coke-head. ‘What’s a – sniff! – escrow account, Niv? – Sniff! – Oh yeah, its like a bank account – sniff! So why can’t I – sniff! – write a cheque?’.”

Did it go to his head? “Fuck no!” he laughs. “Of course it did! I mean, I tried my best. One day I got invited to lunch with Jim Fifield, who ran EMI worldwide, and Joe Smith the chairman of Capitol EMI USA, at some posh private club in London. So I go wearing my leathers. Ridiculous. But I will not wear a suit and tie – you gotta try to hold on to that spirit. Rock’n’roll is the voice of the underdog.

“And you could do other things. Money enables. One time in New Orleans, Iz and I were mistreated by some security guys in a bar. The next day I had 12 of the biggest bodies on the planet flown in from around the country and we went back to that bar and settled accounts.” But, this being Guns N’ Roses, they didn’t get just any gang of heavies. Oh no. Instead they got “football players, weightlifters, Dave Pasanella – then the world’s strongest man.”

“Again, ridiculous,” admits Niven, “but also a real sweet payback for anyone wrongly abused.”And when the hangovers wore off and the bruises healed, there was the small matter of looking after the goose that lays the golden eggs. In the old fable, the farmer and his wife, convinced that the inside of their magical goose must be filled with gold, cut the bird in half, eager to get to the cash. Result: one dead goose and no more eggs.”

- Interview: Guns N' Roses Raise Hell In The City Of Angels

- The chaotic, crazed story of Guns N' Roses' Use Your Illusion

- The 10 Worst Guns N' Roses Songs

- Guns N' Roses, Metallica and the Greatest Rock Show on Earth

It was Niven’s job to make sure that didn’t happen to his boys. “Slash and [Great White frontman Jack] Russell can be as fucked up as they want. I can’t. Someone has to keep the scavenging wolves at bay – the senior Geffen exec whose wife is an editor at Vogue, and she would just love to have Axl do a spread with models in fur coats, yadda yadda yadda. Yeah, that’s great cred for my band of street urchins. On and on that shit goes: David has to have this track to help sell that turkey of a Cruise movie. It’s endless. But we all felt the pressure. Appetite… – how do you follow that? Use Your Illusion was oversized in an attempt to over-compensate for that fear. There is actually one really good record in there somewhere.”

In the midst of all this, his relationship with Axl – never good in the first place – deteriorated. “Against my better judgement I agreed to work with [Stradlin’s solo project] the Ju Ju Hounds. I knew it would drive Axl bat-shit and create problems for us both. But I felt a commitment to Iz that I couldn’t deny.

“But there was always something. Nothing was ever good enough. I do remember, in what may have been one of my last conversations with Axl, trying to explain why people were afraid of him, and why this queered most of his relationships and why he wasn’t getting the responses he wanted. Maybe it was too much for him to hear that he could come off as a ‘prickly bastard’ when he wasn’t intending to be one. I don’t know. You ask him. He’s probably got it written down in a notebook somewhere.

“Axl always had a problem that I worked with other bands, one of which [Great White] predated my commitment to Guns by years; and that I made it clear that I represented the interests of all five signatories of the contract, not just and exclusively his. But I was managing a band, not just a single person. For example, Axl wanted me to cancel the Aerosmith tour in 88; the rest of the band wanted to go. So we went, and waited to see if he would turn up. He did – and then refused to speak to me for a month. He came around eventually. You spent a lot of time waiting for Axl to come around.”

The relationship between manager and singer wasn’t the only one in decline. “There was always an upstaging thing going on between Slash and Axl,” says Niven. “Every now and then you’d see Slash kinda not be his best mate up there on the stage; a shoulder turned at the wrong moment. That happened. The band culture could sometimes foster a vein of real unpleasantness. They weren’t the fuckin’ Monkees.”

The end came in March 1991, when Niven was in New Jersey with Great White. Axl called from LA. “‘I can’t work with you any more,’ he says. ‘Okay, Ax, I’ll be back in a couple of days. Let’s have dinner and talk about it’. ‘Okay,’ he says. And that’s the last time we ever speak. Did I see it coming? No. Was I surprised? No. It would have been classy to have had dinner and agreed to go our separate ways, acknowledged with honour what we achieved together, but Axl is Axl. Thank God he gave himself to rock’n’roll and he’s not a despot running a country. Iz once famously described him as the Ayatolla. And as such it is my understanding that he said it was ‘him or me’ if the band wanted to do the Illusions tour. And I can’t sing like he can, that’s for sure.”

In the end, says Niven, “I paid millions to get Axl out of my life. And here’s how: I had a 17 per cent commission in perpetuity. That means that anything released, mastered or negotiated during the term of my contract was commissionable forever. My original contract was renewed in 89 for a further three or so years. It would expire in 93. At the time it was renewed I was offered a raise to 20 per cent. I turned it down. Axl fired me in 91. That means that the sales of Appetite…, …Lies and Use Your Illusions were all commissionable – forever.

“To get Axl out of my life I sold those rights back to the band for $3.5 million. I did not want to deal with him again. Now that’s a decent chunk of change, but Geffen had only paid royalties on about five million albums total at that time. Imagine how much I had still coming. [Appetite… alone has sold 30 million copies.] The settlement I took is not anywhere close to what I was due and had earned. And after you pay the taxman his third, and your partners [‘the Stravinski Brothers’ credited on Appetite… were Niven and two silent partners], it’s not quite the same golden egg. But that’s how burnt out and disillusioned I was.

“As regards his remark about me getting a payday from Geffen from renegotiations, let’s get some more facts straight. I have a right to defend myself against this guy – there are people who believe what he says, and I may want to work with them some day. Firstly, both the managers of Aerosmith and Whitesnake tried to get renegotiations on existing contracts around this time and failed. I think I’m the only person to leverage a re-negotiation out of David Geffen on an existing contract. Once the negotiation was begun it was the responsibility of the band’s attorney to complete it. Their royalty rates were increased by 30 per cent. There were other refinements – better advances etc – but since when I was fired I sold my rights back to the band I didn’t benefit from any of it. I also got the first major headline tour in place. And then I was fired. Nice.”

Niven wonders if his sacking was part of a bigger play by Axl to attain control of the Guns N’ Roses name. “What I find interesting is that after I was fired, by his own admission Axl took the band name as part of the Geffen renegotiation.

“I believe he got rid of me to do that, among other things. I think that he always intended to take total control. And he knew I would not stand for such a move. I could be wrong, but I rather think there you have it.”

In his online rant, Axl denied any such premeditation, claiming that his ownership of the name was just a natural development, agreed by the band: “At that time I didn’t know or think about brand names or corporate value etc. All I knew is that I came in with the name and from day one everyone had agreed to it being mine.”

He claims that the rest of the band cooked up the story about him refusing to go on stage until the name was signed over to him only after they’d realised the value of the GN’R name (“In my opinion the reality of the shift and the public embarrassment and ridicule by others for not contesting the rights to the brand name, were more than Slash could openly face…”), stresses that he is entitled to the name (“I didn’t leave Guns and I didn’t drive others out”), and says Slash left to “go solo [after trying] to completely take over Guns”.

Niven was gone by then, but claims he never saw evidence of any such thing: “Slash never attempted to run the band, from my point of view. He had a hard enough time even runnin’ a bath.” Whatever the truth, they might have to change the old story: it turns out this golden goose cut its own heart out.

Of the new GN’R, Niven says: “Everyone has the right to make the music they want to with whomever they wish. But just be up ’n’ up about it. All this ‘last man standing’ stuff from Axl is horseshit. He wore us all out. Drove us all off. And for a personality like Axl, only solo work makes sense. If he wants to be Elton Rose then more power to him. He has the talent. But don’t pretend that one person alone represents the idea of Guns N’ Roses. That band, in my opinion, played its last show on April 7, 1990. Farm Aid, Indianapolis.”

Over the years, Axl has become almost a pantomime villain. Aren’t some of his actions understandable? Surrounded by unreliable drug users and alcoholics, was it any wonder that he would try to seize control, his shot at the big time in danger of being blown?

“Let’s see now,” says Niven. “Before the release of Appetite For Destruction – note the fuckin’ name – Axl had no previous experience of Slash and Izzy and their behaviour. Right. They were brought together during some American Idol auditions. Yeah, that was it. The Hell Hole behind The Guitar Centre never existed. Iz never sold smack. Axl was never on the run from the cops. They were all just little ol’ choirboys before all those awful temptations of success occurred.”

He laughs: “C’mon. It actually got toned down once the career began to roll, and Doug [Goldstein, Niven’s former assistant who succeeded him as GN’R’s manager] began his clean-up duties. Y’know what I am proud of? That they are all alive today. It wouldn’t have been the case if history had taken other turns – if we hadn’t done our best to keep everyone alive.”

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock issue 129