Jimmy Page suffered most from the loss of Led Zeppelin. While Robert Plant was plainly relieved to shed the responsibility of helping to keep the Zeppelin legend alive, and John Paul Jones seemed content to retreat even further into the shadows, easily reverting to being plain John Baldwin, doting father and family man, Page was left absolutely bereft, both musically and personally.

As he told me not long afterwards: “There was a point after [John Bonham died] where I hadn’t touched a guitar for ages and I just related everything to what had happened, the tragedy. But I called up my road manager one day and said: ‘Look, get the Les Paul out of storage’. He went to get it and the case was empty! I think somebody took it out and borrowed it. They shouldn’t have. It eventually reappeared. But when he came back and said the guitar was missing, I said: ‘That’s it, forget it, I’m finished’.”

In the immediate aftermath of Zeppelin’s demise, Page been coaxed by near-neighbour Michael Winner into recording the soundtrack album for the director’s Death Wish II movie. But it wasn’t until he teamed up with former Free and Bad Company vocalist Paul Rodgers that Page began to discover a musical life for himself after Zeppelin. With Rodgers also “still recovering” from the loss of his own outfit, “he was one of the few people that could probably relate to what I was going through.”

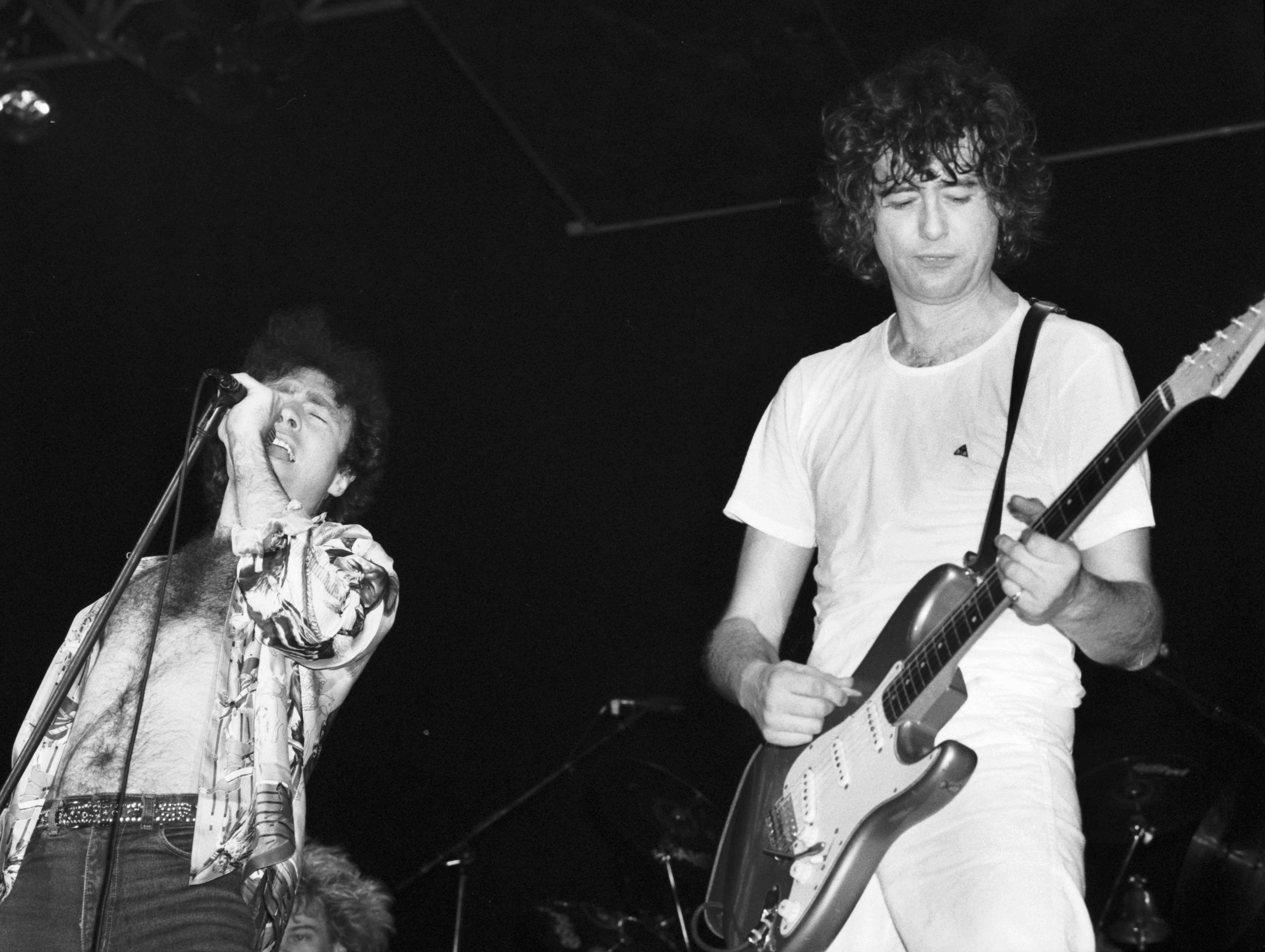

The result was The Firm, a four-piece also including ex-Uriah Heep drummer Chris Slade and former Roy Harper bassist Tony Franklin. Page says it “saved” him. “I was shattered at the time.” The Firm allowed he and Rodgers to “get out and play and really enjoy ourselves.”

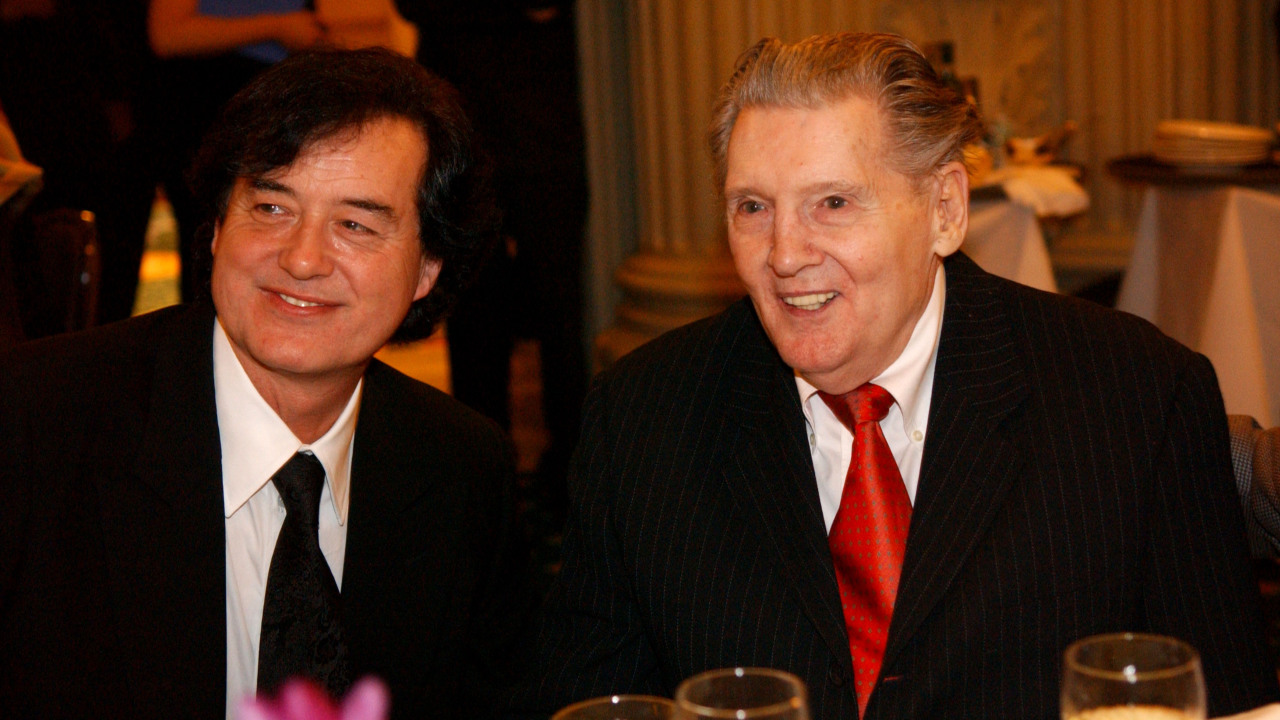

Both men (pictured above) refused to perform any material from their former bands, relying solely on the much smoother – some said blander – funk-tinged sound of the new outfit, although Midnight Moonlight, the closing track on their self-titled, debut album in 1985, was actually an unreleased Zeppelin number originally titled The Swan Song (which, legend has it, Plant had refused to sing). A second Firm album, Mean Business, was released in 1986, but neither records troubled the charts for long, despite the band becoming a huge live attraction in the US.

By 1988 The Firm had dissolved and Page was ready to release his first and only solo album, Outrider. Featuring Jason Bonham on drums and an array of guest vocalists (including Plant), Outrider was a commendable but unsatisfying collection which, like The Firm, failed to set the charts alight but did allow Page to tour Britain and America solo for the first time, the highlight of the show being an instrumental Stairway To Heaven “which the audience sings for me.”

The plan had been to release a second solo album, but Page’s new US label, Geffen, suggested he team up with David Coverdale.

The short-lived Coverdale/Page was surprisingly invigorating. In the absence of the full-on Zeppelin reunion that Page no longer made any secret of craving, working with Coverdale was the next best thing. Certainly the eponymous album they produced in 1993 was the closest thing to Zeppelin Page had recorded since the break-up, a fact reflected in its Top 10 status here and in the US. With Coverdale inspired, too, on titanic blues-rock workouts like Shake My Tree and Absolution Blues, it was not long before a publicly smug but privately piqued Plant was on the phone to Jimmy suggesting something similar – but different.

Officially, the spark had been an invitation from MTV to play in their Unplugged series. In truth, with Plant’s solo career flagging and Page no better off left to his own devices, the chance to join forces was too good to miss. Page would have been happy for a full-on Zeppelin reformation. Plant, however, was still against the idea, arguing that the pair could enjoy the kudos of being back together without any of the problems of using the Zeppelin name – comparisons with the past; being regarded as heavy metal – by not inviting John Paul Jones along.

Despite the fact that the resulting 1994 televised concert and No Quarter album were built almost entirely on the Zep back catalogue, the judicious addition of an 11-piece Egyptian ensemble, plus four brand new numbers, obscured the fact that this was virtually a Zeppelin reformation in all but name. On tour, where audiences had come to hear the classics, the illusion was harder to maintain. Plant was refusing to sing Stairway To Heaven, and a new enmity between the two was brewing. There was a second album, the good-not-great Walking Into Clarksdale, but the pairing ended at the start of 1999, when Plant changed his mind at the last minute about an Australian tour, claiming that he “didn’t know how many more English springs I would see.”

A furious Page turned to the Black Crowes, who he successfully toured America with later that year with a set built solidly around the Zep catalogue. The resulting album, Live At The Greek, was not only a bigger hit than Walking Into Clarksdale, it was also more enjoyable.

The odd collaboration aside – very odd, in the case of the 1998 performance on Puff Daddy’s rap version of Kashmir – mainly, Page has spent his post-Zeppelin career concentrating on keeping the flame alive, from producing the excellent four-CD Remasters box set in 1990 to overseeing the ground-breaking twin release of the superlative six-hour DVD collection and double-live CD How The West Was Won, in 2003. With the Zeppelin legacy safely assured, he has been working on and off for the past couple of years on a second solo album, due for release sometime in 2007. What that will be like, and who might be singing on it, we will have to wait and see. The only thing certain is that it won’t be Robert Plant. (Sadly, eight years on, we still await that solo album).

This was published in Classic Rock issue 102.