Sky’s gone red again. The noise is whirling rotor-blades glancing off rocks, and human voices stretching and screaming as one into a fierce, hot ash-flecked wind. A 90° incline with failure snapping at our heels and fate spunking in our faces. Traction. Grit. Endurance. Love and death in the afternoon going on here at Blood Mountain.

I’m listening to the new Mastodon album, Blood Mountain, and instead of noting the skillful synthesis of their key influences – Melvins, The Call Of Ktulu, bits of Kyuss, bits of Slayer, seasickness and hallucinogens – my head’s stuck on two things. One: the colour of the sky in a level of a computer game I haven’t played since I was 13. Two: an abstract symbol of cod-philosophy in a ropey 1960s sci fi novel. It’s making my head feel fucking trippy.

“The blood could also mean ‘blood brothers’, you know?” suggests Mastodon guitarist Bill Kelliher. “Like, family as well. Our mountain. It’s our journey.”

“Or it could mean the fuckin’ blood of many slain, tryin’ to get to the top,” snarls his Flying V-toting counterpoint, the ink-scrawled, demon-eyed Brent Hinds.

“It could be the blood of the devil that is us,” chuckles Bill, with only the mildest mock-profundity.

“Could be the fuckin’ blood comin’ outta the devil’s penis,” rages Brent, tattooed arms flailing around his head, eyes flying-saucer-wide. “Peein’ on the top of the mountain, tryin’ to wash us away… ”

“Wash away the sins. Of humanity,” says Bill solemnly. “That’s right, dude.” So what happens at the top? Brent bounds into life, suddenly ferocious in the last minute of our hour long interview, glad that someone’s finally asked him an intelligent question for once. His voice distorting on our tape recorder as he manically rattles out his masterplan: “We place the crystal skull on to the top of the mountain where the blood is pourin’ outta the fuckin’ king of the dudes and we place the crystal skull inside of his belly – on this, like, perch – and get these like crazy magical powers and we all grow unicorns and chocolate feathers and we ride into outer space and we write a new album about the universe.”

“Yep,” says Bill. Solemnly.

Even if you haven’t been on the Mastodon trail since the beginning, tracking the hairy, lumbering four-headed beast as it crushed clubs and toilet venues around the world – never pausing, always looking for fresh meat – you will almost certainly have picked up a copy of 2004’s seminal Leviathan after it was hailed by Hammer as officially the third greatest metal album of the past 20 years a couple of issues back.

Despite its status, on first listen Leviathan doesn’t scan like the Master Of Puppets-esque masterwork that the Mastodon faithful proclaim it as. There isn’t any of the naïve, greedy, wolf-eyed ambition of young gods like Trivium. In its place there’s creaking beams, lurching seasick riffs, baleful bellowing and an epic story about whales. In many ways it’s scarcely even metal, Mastodon seemingly having more in common with under-the-radar noise assassins like Lightning Bolt or Comets On Fire than metal royalty like Metallica.

Mastodon didn’t ever pledge allegiance to any flag. They’re not here to defend the faith. They don’t exist to support Iron Maiden. They probably could care less what people think of them.

So why should you care?

Because Mastodon are monumental. Leviathan is monumental – like Slayer’s Reign In Blood, rather than a ‘classic metal album’ in its own right, it’s simply the most accurate, fully-realised representation of what Mastodon is, or was up to that point. Their endless live shows are monumental – non-stop touring has whipped them into nasty machines and a global audience into begging for something spectacular and soul-saving.

Having made the jump from cult noise stable Relapse Records to the glittering palace of evil that is major label Warner Brothers, Mastodon are now equipped with the necessary firepower to blow holes into heavy metal’s armour. They could change everything. They have a new album, it’s called Blood Mountain.

“My grandfather has a photo of me in a diaper and I’m huggin’ a bass drum. I just looked at the drum set and it totally made sense for me to be behind that.” Brann Dailor has the look of a younger, prettier Josh Homme. Onstage his kit is dappled with polka dots like Randy Rhoads’ iconic Flying V guitar, and the doomed guitarist’s image adorns his kick drum. It makes sense, in a way – Brann is a virtuoso drummer, simply the best in metal this side of Dave Lombardo, but his drumming is supremely lyrical, not propulsive. It ripples into crescendos – crashing waves of percussion on Leviathan – spiralling into weirdly melodic passages, like Rhoads’ solos, while Bill and Brent’s guitars crunch angrily beneath him, like two slowly duelling Triceratops.

“My next door neighbour, John, would put this Judas Priest record on and I would sing to the record and he would play drums,” he remembers. “And we’d call my mom and his stepdad and give them concerts. I would steal my mom’s strobe and black lights and put up some posters and we’d be like, ‘Alright! We got ourselves a band’.”

Somewhere along the line Brann met Bill in their hometown of Rochester, New York, forming a musical alliance that threaded through myriad noisy incarnations.

“The first band was called Crinkled Pig,” recalls Bill. “We did all Sex Pistols and Ramones cover songs. And then there was Skullduggery, Death Comes Ripping, Lunchlady. Butterslacks. Uh… Girdle. Nurse Ratched. Brann and I played in a band called Lethargy. Goofy tech metal, slidey riffs, lots of harmonies, just really fast grinding sick vocals – really hard shit to play.”

After a stint in prog-metal mainstays Today Is The Day, the duo relocated to Atlanta on the eve of the millennium with the intention of advertising for new jamming partners. Within days they’d met another pair – Brent Hinds and his bass-playing best-buddy Troy Sanders, who shared a similar seven-year symbiotic history – at a High On Fire gig. Immediately, before any songs were written, Troy booked a tour for the unnamed group – who then had to recruit a vocalist (one Eric Saner), and nine songs were hastily written and recorded, to be sold at gigs. Saner soon departed the band – with Troy, Brent and assorted guests furthermore dividing vocal duties between themselves – although the demo recently resurfaced on Relapse under the title Call Of The Mastodon.

“We put these songs together and we said our music is never gonna go anywhere unless we take it to the people,” explains Troy, the towering and eminently likeable frontman. “We’re not gonna write a cool song, record it and it’s gonna get played on the radio somewhere. That was just never gonna happen.”

- Giraffe Tongue Orchestra release Crucifixion video

- GALLERY: Killer Be Killed at Soundwave 2015

- Mastodon's Brann Dailor discusses his pre-Bloodstock nerves

- The A-Z Guide To Mastodon

Conceived from the start as a touring entity, over the next couple of years, the “Dirtier… less layered” onslaught of Mastodon expanded, mellowed, got stronger and stranger – with a definite stylistic jump between 2001 debut Lifesblood and 2002’s Remission. But the switch from simply being face-melting firebrands to Mastodon, the canonised auteur of Leviathan, wasn’t prompted so much by a musical redress as an ideological one. Brann saw the phrase “salt-sea mastodon”, referring to the monster whale in the opening pages of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and the band immediately fell in love with the parallels between the rolling, crashing unfathomable nature of the ocean and its whale – not to mention Ahab’s perilous voyage of discovery – and their own, then-undirected, tempestuous force.

The lyrics and – crucially – music for Leviathan were scripted to Moby Dick’s narrative, evoking almost magically the brine-drenched spirit of Melville’s work in a ferocious, alive and totally unexpected delivery. “Once we had something to look at, it brought us together,” says Brann. “We were extremely focused after that. After Leviathan we had a reason to write songs.”

Really, more than simply nicking an idea out of a dog-eared paperback left in a tour bus bunk, what changed is that Mastodon had stopped looking to other rock bands, other music, for inspiration, and looked instead for something more elemental. Bigger. More pure.

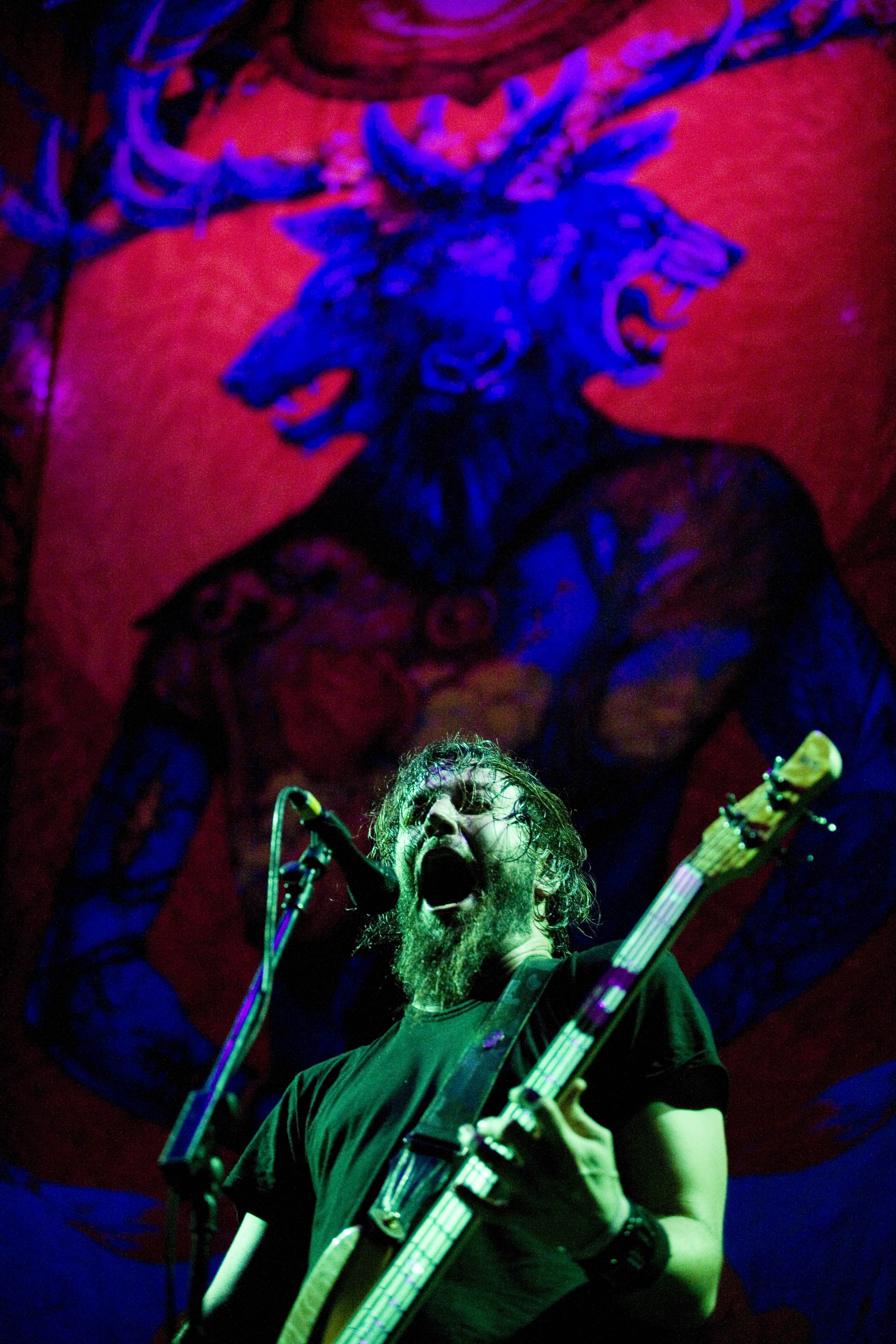

The noise is horrible, loud, fantastic. Troy clamps his hands over his ears, the grinning, perma-gurning face-of-Mastodon contorting to a painful grimace. Hammer photographer Mick Hutson pauses the shoot and looks up, waiting impatiently as the train thunders over the rickety, corroded Chicago railway bridge above us. Upon hearing it, Brent immediately snaps into position: legs splayed, head thrown back, arms slashing furiously at an imaginary Flying V, howling in delight as he envisions that abrasive metal-on-metal grind screaming out of guitar and speaker. “Oh man,” he mutters, shaking his head. “If only.”

Tonight Mastodon are performing at Chicago’s opulent Aragon ballroom – galleries fashioned into battlements and towers, a breathtaking vista of the cosmos, a painted galaxy, splashed across the ceiling – supporting Slayer on the US leg of their Unholy Alliance tour.

“I’m not the biggest Slayer fan in the world,” Brent admits. “I’m just not. But I do realise Slayer are one of the best bands in the world. You see them play live – they’re fuckin’ amazing! They BLOW ME AWAY every night, I’m like, ‘holy shit dude’.”

Don’t you see any parallels between what they do and what you do?

“I really don’t. To be honest with you. Because they totally go out there and thrash and shred. And we go kinda out there and fuckin’… POUND and… DROP. You know? Like BOOOM!! Waah!Krah!GAHkraar! BOOM!! We’re more like that. And they’re more like raddlyraddlyrahWOOROOWOOROOraddlyraa ggggggggh!!”

Brent’s so cool. He never stops moving, never stops thinking, constantly grinning, twitching and verbalising – fixing you dead in the eye as he does so. Throughout our interview he will alternately fiddle with the substantial pile of mary jane in front of him, or snatch up a barbell – pumping iron and hissing out breath as we talk or he thinks, his head continually reeling back and forth.

In terms of writing and decision-making Mastodon are very much a democracy, but Brent is Mastodon’s Kerry King. Brent is fucking intense. “But I think we’re both doing the same thing,” adds Bill. “We’re both punishing,” considers Brent.

How do you feel when you’re playing your music? Do you think different? Do you see things?

“Yeah,” sighs Bill, nonchalantly. “When I’m in front of fuckin’ thousands of kids and my amp’s fuckin’ blarin’ and I’m just rockin’, jammin’ out, I feel… I feel good. It feels awesome. It’s a powerful thing.”

Brian Chippendale from Lightning Bolt once said that when they play, rather than model themselves on another band – like Slayer or whoever – they try to model themselves on, like, a storm. Or he envisions that if he drums fast enough that a weird magical being will appear, or a door will open up and elves will come running out. Do you visualise your music like that?

“We fuckin’ LOVE Lightning Bolt!” Brent explodes at the mention of the infamous math-metal duo. “Yeah, all that shit happens if you’re tripping on mushrooms or somethin’.”

“We had a couple of songs on Remission,” offers Bill. “For instance, we couldn’t come up with a name for one song, Trainwreck. And someone was like, ‘Man, that fuckin’ song! I can just envision this train like goin’ off the tracks and fuckin’ exploding!’. We were like, ‘Wow, cool!’. Or Motherpuncher? Our old singer was like, ‘Man! This song makes me wanna punch my mother!’.”

“But as far as the way I physically feel when I’m playing music,” returns Brent thoughtfully, “I feel amazing. That’s why I do it so often and I thank my lucky stars that I get to do it for my livelihood nowadays.

“But, um, yeah, it makes me feel like fuckin’ portals and magical gnomes and all that shit. Totally.”

Do you ever try and write while tripping?

Brent snorts and shoots us a dismissive glare, like we just choked on my first doobie. “Oh fuck, yeah!”

What do Mastodon sound like on mushrooms?

“Oh, dude! I would totally love to take mushrooms and listen to Mastodon, anytime. I have mescaline! It’s this powder and it makes the walls fuckin’ start breathing and all that shit. It’s an American Indian thing.”

“They use it in a lot of rituals,” explains Bill. “To get on with mother nature. I dunno, I don’t mess with that shit any more. I did enough acid back in the day.”

“I might do a little bit of mescaline on this tour but that’s it,” reasons Brent. “I would never, ever do anything to fuck up the show. If I fuck something up I’m gonna get bummed out.” He darkens, glowering. “I’m gonna be Bummed Out Brent. And no one wants to be around Bummed Out Brent.”

So… Blood Mountain. It’s not a particularly long album – 50 minutes – but it feels epic. It feels strenuous and hard; something that has to be endured. A trial by fire – something occult. It has moments of relapse, of tense, locked repose, but as exhilarating and fist-pumping as the songs are, everything feels steep – uphill. Maybe it’s the fiery, ascending guitar lines and cascading drums, or maybe it’s the ever-onwards, triumphant surge in Troy’s vocals as they urge us on.

Listening to the album from start to finish, you get the sense of ascending, enduring. Of climbing Blood Mountain.

“That’s exactly it,” exclaims Brent. “The sequencing, the climax of the middle… A band – or a group of people – tryin’ to fuckin’ climb a blood mountain, and it’s called Blood Mountain because it’s a fuckin’ dangerous, nervous situation, you know? It’s like tryin’ to do music, you know?”

“We’ve just taken on Warners now, and now it’s like this fuckin’ huge mountain that we’ve got to climb to the top of,” says Bill.

“Warner Bros is the blood mountain,” affirms Brent. “We’re also tryin’ to touch on all the elements as well. Like Remission had a fire theme – burning man and fuckin’ horses on fire and there was a flame for the logo. Leviathan was water. Blood Mountain is a very earthy album. The next one will probably be very astrologically oriented.”

Blood Mountain… it’s got this weird ambience to it. I’ve been trying to put my finger on it for ages, but the closest I can come up with is this really abstract association. It reminds me of a level in the 90s computer game Doom, where you’re outside and the sky is just this strange deep red colour. But instead of it being a demonic or scary thing, it’s just this weird melancholic feeling – this empty, lost feeling. How do you engineer a mood like that?

The non-musical associations with the band – the name, the artwork – seem to feed into the music as much as describe it. Like the entity that is Mastodon is a kind of magic spell or whirlpool that drags in these different elements and associations and consumes them to make itself stronger.

“Basically it all stems from dreams,” nods Brent. “Dreams talked about and then turned into artwork and songs and situations.” He pauses. “There’s a lot of Masonic imagery too, which I love.”

Brent, the last time you were in this magazine the interviewer asked why you had a depiction of Baphomet tattooed across your back and you refused to say anything…

For the first time since I’ve met him, Brent quietens, his voice shrinking sharply. “That’s just a personal thing.” That’s what you said last time! He snaps defensively, “Yeah, well, what – do I have to answer different this time?”

What have you got to hide?

“Well…” he takes a deep breath. “I’m a Capricorn and I’m a Pagan. I don’t believe in one thing, I believe in the universe. Baphomet is woman, man, goat, child – it has every element to it…” He gets visibly agitated and squirms uncomfortably. “That’s why I fuckin’ hate talking about this – people think it’s the devil and it’s not the devil at all. The devil is not Baphomet. The devil is Beelzebub. Two totally different things. This is a Pagan icon. I’m in love with goat imagery because I’m a Capricorn, I think. And I really don’t feel like describing that to most people, because to me, it’s really none of their business.”

“He was a goat in a previous life,” smirks Bill.

“I was a goat in a previous life!” Brent roars. “I wouldn’t doubt it, dude!”

The only other reference point I have for Blood Mountain is equally clumsy and suitably esoteric. In Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? (the novel that inspired Blade Runner) future society is founded on a humanistic philosophy known as Mercerism.

To commune with Mercer – not so much a prophet as an eternal symbol of endurance and perseverance – citizens plug into a kind of virtual reality machine which allows them to visualise a mountainside. A barren ascent, with an old man in rags, Wilbur Mercer, slowly climbing, and the thoughts of whoever was logged in to the machine at that time humming powerfully as one as they struggle to ascend – pelted with rocks from unseen aggressors. Communing daily with the interface, no one ever reaches the summit. But that isn’t the point.

It’s all a bit far-fetched – not totally – but watching Mastodon grind out their weird, muscular hymns to Cysquatches and sub-Paganistic (Paganism being a similarly humanistic and individually interpretive philosophy) forest deities, in the Aragon Ballroom, in Chicago, with a throng of metalheads saluting them, surging towards them, urging them on, you glean the relevance of the concept.

Mastodon, like the best heavy metal, engender a sense of community – of faith. The most human thing we can do is endure. Like Mercer, Blood Mountain is a symbol of abstract faith. A demand that we should all aspire to a better time and place.

Mastodon’s metal is supreme rocket fuel. Ascend to this.

This article originally appeared in Metal Hammer #156.

Try your hand at the Prog Metal Quiz by clicking on the link below.