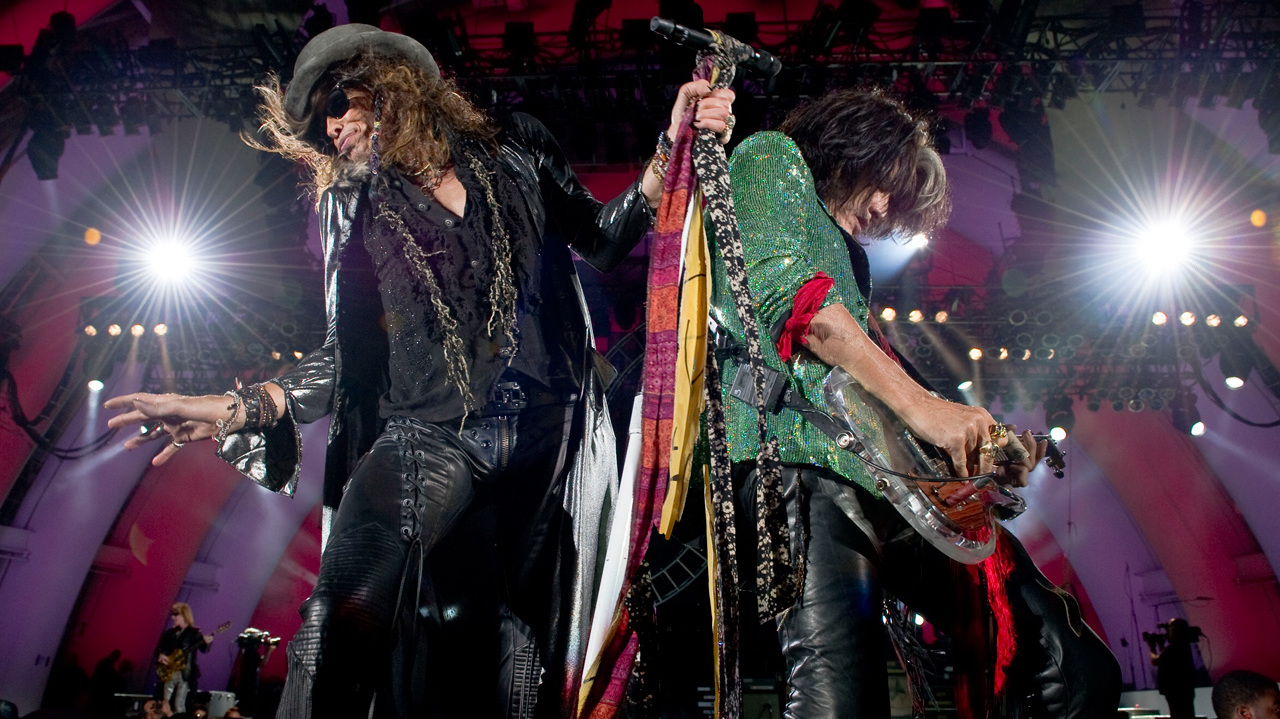

On June 11, Aerosmith will headline Download. The familiar bluesy chug of Joe Perry and Brad Whitford’s guitars will drift across Donington Park, Steven Tyler’s feral yowl laid on top. And tens of thousands of people will howl along, perhaps not contemplating the miracle that the five men on stage are able to play for them. Leave aside the years of living so fast it broke all speed limits, the fact is Aerosmith don’t make life easy for themselves.

Even now, as they traverse Europe on their Aero-Vederci Baby! tour, what would normally be a victory lap comes shrouded in their traditional confusion: is it their final tour? Well, that was the word from Tyler, but then he came forward to say that when he gets in the room with the guys, after all these years, he can’t imagine stopping. Will there be another album? First Perry says they’re postponing their US tour to work on new material, then he tells Classic Rock… well, let’s not spoil that. Read on and you’ll find out.

That follows plenty of acrimony between the pair over the past few years. Perry was unimpressed with Tyler’s country album last year. “Hey, if I didn’t know him when I heard the song, I’d go: ‘It’s okay. Next,’” he said of the single Red, White & You. “I’m not going to say anything else about that.”

Tyler responded by saying: “You know what? Jealousy runs deep in this family.”

The pair’s autobiographies weren’t exactly glowing about each other either. Perry sniffed that Tyler was aloof, suggesting in interviews he had always been more interested in the trappings of stardom than in making music. “He says that he carried the band for forty years,” Perry told one interviewer. “Hey, pal, do you ever look in the mirror?”

Tyler’s own book lifted the lid on the years of feuding, and made plain that the Toxic Twins might have got their name from their relationship as much as from their personal habits.

Yet here they are, 46 years on from forming in Massachusetts, back in the saddle for another lucrative loop around huge stages, and willing to talk about life in Aerosmith, what the future holds – although who knows how their plans might change between them speaking to Classic Rock and you reading this – and the music that made them fall in love with rock’n’roll in the first place. Tyler, speaking at his home in Maui – a house paid for by his stint as a judge on American Idol – is colourful and effusive, opening the conversation with a mockney “How’s it goin’, me old China plate?” Perry, speaking well after midnight in LA a couple of days later, is less effusive but perhaps more revealing – at least until Johnny Depp arrives at the studio and he leaves to work on tracks with his bandmate in the Hollywood Vampires.

Both say the right things, though they often say the wrong things too. When Aerosmith do finally call it a day, no careers in diplomacy await this pair.

What gets you back on the road with Aerosmith, apart from the prospect of large sums of money?

Steven Tyler: I love my band. I love nothing better than my children and being able to say I was in a band that played clubs and made it big as a brotherhood. Unlike the rest of the guys, I don’t give a shit if we go on stage and don’t make any money at all. I just love playing with the band. I beg of them, I need a couple of days off between shows, just like Zeppelin did or the Stones do. I can’t do it like the old days, when I’d do three shows in a row. I need to take some time off and I need the band to respect me for that. Sometimes it’s not seen like that, but I think we all enjoy each other’s presence, and I think everyone loves the money and I think everyone loves being in this band. Nobody makes any more money than the other guy.

Would you still want to play live if you weren’t getting the huge pay cheques?

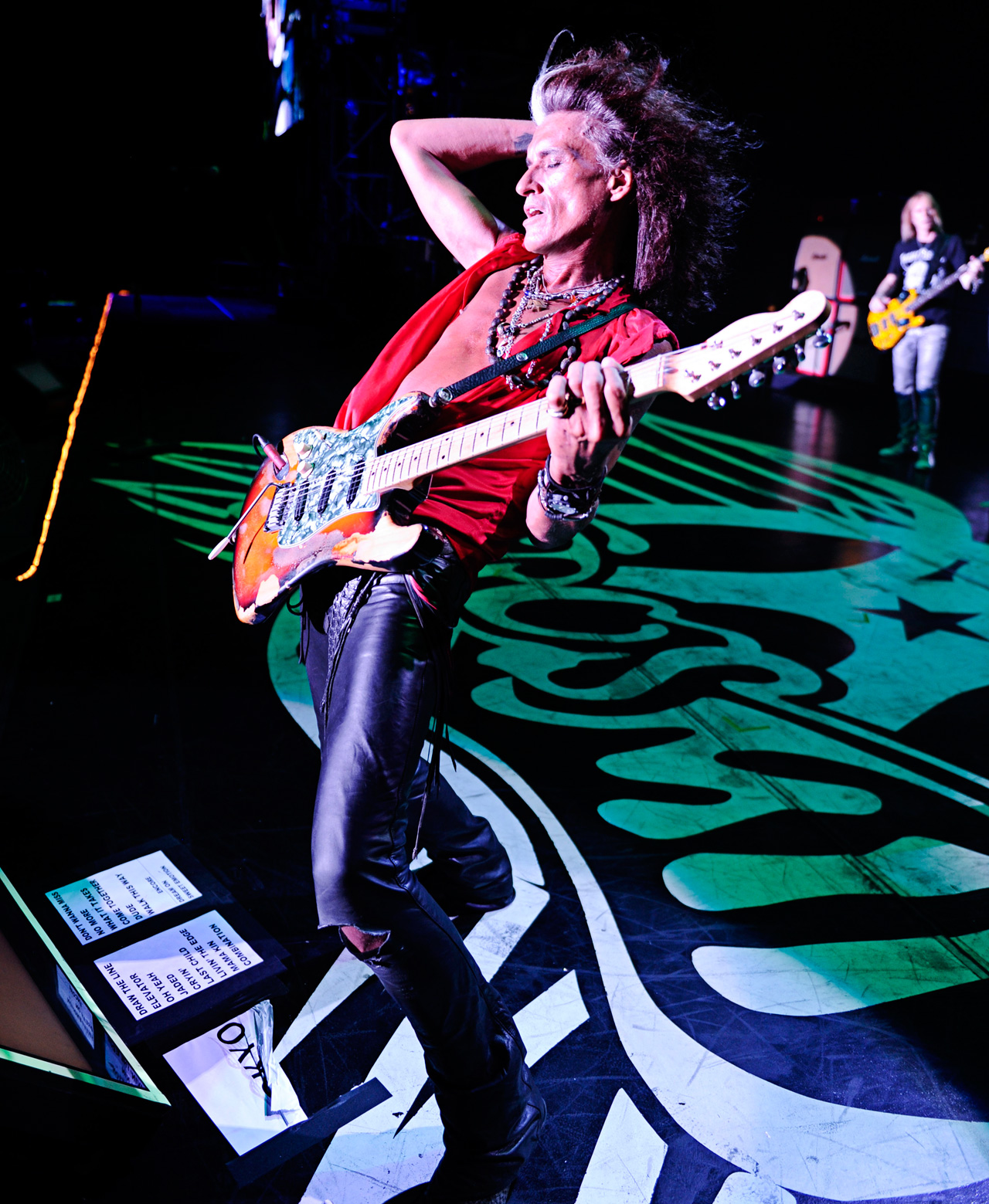

Joe Perry: If it wasn’t for the audience I wouldn’t bother. But when the band starts playing those songs and we hear this reaction, then tonight I’m going to try to play this as best as I can. Yeah, I’ve played it a thousand times, but when the audience is there with you and they’re hanging on every note, it’s like you’re playing it for the first time again. I think about it, and I go: “I’m going to go out to play fucking Cryin’ again?” But I know when I get out there and play some of those riffs, the people respond and that brings it into the moment where I’m not thinking: “Well I played that five times in the last month.”

What’s the hardest thing about playing live these days?

ST: The hardest thing for me is doing all these meet-and-greets. I don’t like doing them any more, but they make everybody money. I love going on stage and playing, and taking a couple of days off and actually seeing where the fuck we are – maybe going to London and going shopping at Harrods for one fucking day – whereas the band just likes to rip through a tour. When you’ve been on tour for a year, your kids don’t even know who you are. It can be rough.

Are your feet up to a long tour?

ST: I’ve burned them out from running around on stage for more than forty years, so they’re a little fucked up, but I’m all right – better living through chemistry, right?

You don’t find it odd to be getting on stage with each other, given the things you’ve all had to say over the years?

ST: I’m just really grateful after all these years to be in Aerosmith, even though these guys are a bunch of crybabies every now and then. And they bitch when I do a solo record. But as I always tell them: “You’ll miss me when I’m quiet.” They say it’s LSD: lead singer disorder. I think it’s the opposite: I think a lot of bands are very jealous of the lead singer. How could it not be? Or of the guitar player.

JP: There’s a lot of stuff that goes on. There’s a lot of acrimony. Stuff that’s been done among all the guys. That’s the stuff that breaks bands up. It’s a private club that no one else can enter. It’s still the five guys, and sometimes we’ve had our arguments that have someone walking out of the room, and people saying: “These guys will never talk again.” But the next day it’s business as usual. And that’s the way it is today.

Yes, but most people’s arguments aren’t in the newspapers for millions of people to read about.

JP: We would never make up. We would just carry on. We would leave it alone, leaving the corpse on the floor. And then just carry on. It wasn’t like: “We’re all brothers, everything’s fine.” None of that shit. It was: “Rehearsal tomorrow, we’re gonna play.” Like I said, we leave the corpses lying on the floor, and they would stack up, but it didn’t stop us from playing. Hey, there’s no law that says a rock’n’roll band can’t get along for fifty years. but it hasn’t happened yet. But when the band is in a room together it doesn’t change – that feeling that you’ve got to keep it tight – and that’s the ongoing thing that keeps it together.

Steven, you’ve said that seeing the Rolling Stones in New York in 1965, when you were seventeen, was the moment when you realised the possibilities of rock’n’roll. What was so revelatory about the Stones?

ST: I think the same thing as Janis Joplin: freedom on stage. And there was the way Mick interpreted the English blues, and the way they looked. It led the way to freedom for me, and so did Janis Joplin. I had no idea you could go up on stage with an open bottle of Southern Comfort and smoke a joint and get lit up, you know? I came from an era where passion was terrible: do as I say, not as I do. It was segregation, Elvis Presley only being filmed from the waist up – censorship. I fucking hated it. Then in the 1960s, here comes Carnaby Street! The clothes, the music. So much great music. In ’64 there was a record store downtown and we’d go and buy all the English imports. I would go to this one store in Greenwich Village, and Frank Zappa was always in there. He’d be buying classical music, which I’d had enough of because my father went to Juilliard. The Merseybeats, Tobacco Road by the Nashville Teens … Jesus, just all of it.

Were the Stones the magic group for you as a kid too, Joe?

JP: Not really. It was hearing the second English invasion. All those bands coming over and playing American blues, like Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, that’s what captured me. That’s when I fucking felt like there was something here I can do, and I don’t hear it so much from American bands. I liked what the English bands were doing so well that I gravitated to that. I tried every chance I could to see every band, because those were the bands that excited me, that gave me life, gave me a window into something. I wasn’t hearing that from American bands. But I knew there was something I could throw into that mix if I put the right thing together.

Which shows were your highlights as a teenager?

JP: I got the chance to see the Dave Clark Five. It was probably their last tour of the States, and I thought: “Wow! I finally got a chance to see one of the big three bands from the first invasion.” Even though they’re not one of the bands people play a lot now, they were a big band at the time. There was one point where they had more singles on the chart than The Beatles, so for young fans in America they were right up there.

Then I got to see a couple of the old-school kinda tours, where the headliner might have half an hour or the opening act might have had one single, and there’d be five bands on the bill. When I got into the local scene and I got to see bands like J Geils and those cats, I started to feel I really loved what they did, but I could add something to it if I put a band together.

Steven, you went to the first Woodstock as a fan in 1969. What was that like?

ST: Wow. I went with a bunch of people I was in a band with. After three days it had rained so much the water got in the gas tank and we couldn’t start the car, so I got stuck there another two days, which was terrible, because it looked like a war zone. There were tents, Coca-Cola coolers, miles and miles of that. Old blankets and shitty clothes. But what I remember the most was so many raw, beautiful musicians of the time. I got woken up one morning by Jimi Hendrix playing [Tyler sings the melody of The Star-Spangled Banner, imitating Hendrix] on the electric guitar, which no one had ever done before. There were so many great artists, and so many people, and everybody was tripping and walking around naked. It was a very loose and free summer of ’69.

Why do you think Aerosmith ended up capturing people’s imaginations to the extent that not only have you lasted forty-six years, you’re also still headlining shows?

JP: I think coming from Boston, in the shadow of J Geils, we were always trying to prove ourselves. That’s one thing I can agree with Steven on: we always felt like we had to prove ourselves every night, and that feeling carries all the way through. Every time I walk on stage I feel like we’ve got to prove ourselves. I’m still really critical of how the band’s playing. Sometimes you know that if we play certain things the audience will get off on it, but I spend half my night listening to the other guys play and see if we can get working, because I always feel like you’ve got to do a better show. That’s really it. It’s about taking the songs and not deviating too far from what people want to hear, and keeping up the energy.

I’m totally engaged with the other guys, man. Getting it tight and having it lock in. Experience has shown that if we’re there, we usually bring in the audience with us. Maybe it’s because we came up in Boston and so we were always trying to impress people, and it was a tough fight.

ST: I think we always took ourselves seriously, maybe to a fault. A lot of the guitar lines and riffs that Joe would come up with, and I would write the melody and the lyric to, became classics. There’s a good thing I read the other day about being original. I wrote it down: “Everybody is influenced by somebody or something. But if there’s an original, who’s the original?” My mom reading The Jungle Book to me when I was three, four, five, that helps your imagination.

I think it’s lasted much longer than I thought it would and I’m very surprised. I’m a much bigger fan of the Rolling Stones than I am of Aerosmith. It’s what I cut my teeth on. And Janis Joplin and the Everly Brothers. Yet there’s more Aerosmith on the fucking radio than those guys. It kinda pisses me off a little.

If you had to live the 1970s all over again, would you do it the same way? In other words, to be Aerosmith, did you have to live the lives that nearly killed you?

JP: That’s a tough one, because so much of what comes out at one end, you pay for it at the other. I could sit there and go: “Yeah, it would be great if we made these decisions.” But then I wouldn’t have had the experiences to push the other end. I could go down the list: I could wish we’d had a better manager then, someone to guide us better. We were kids then and we did the best we could. So it’s really hard to look back and say: “That would have fixed it”, because who knows what that would have done to the next three months? It’s like they say about time travel: if you go back in time and fix that one thing, you don’t know what impact that’s going to have as time goes on.

I believe everything happens for a reason. I wouldn’t be the musician I am now if I hadn’t gone through the seventies. Good or bad, it is what it is. I don’t spend much time thinking about that stuff. Unless you guys ask me.

ST: Yes, absolutely. What do you think Keith Richards would tell you if you asked him that? It was the way it was, man. It was everybody getting stoned. It was peace, love, and if you’re not with the one you love, love the one you’re with. I’d love to tell you I wish I knew better, but I already was kinda living it. I think musicians have a different sense of reality, because of the language of music we speak. I’m sure you’ve smoked a joint at some time in your life…

And that lofty feeling of Jack Daniel’s and ‘Let me take you down cos I’m going to…’ It’s just the way it was, and it took you places you couldn’t have ordinarily gone on your own. I definitely travelled Trans Love Airways.

Was there an Aerosmith gig that sums up the band breaking through?

JP: It was after the second record came out [1974]. We’d spent a lot of time touring through the Midwest and into Detroit, so we hadn’t played in Boston for a while. When we came back, there was this buzz because Dream On had been re-released. The gig was at a high-school auditorium and people were going nuts. Our manager came in and said: “Boys, I think we made some noise.” And he pulled a lot of money out of his pockets. Up to then we’d been used to getting three hundred bucks a night. But that night, from the energy of the audience and then him coming in, that was the gig I felt like: “Wow, people are coming to see us, and not just because they’re our friends.”

That was an amazing time. And that’s the case with a lot of young bands. I talked about it with Slash from Guns N’ Roses. I talked about it with the cats from the Black Crowes, the guys from AC/DC. There’s that period where you go from being a bunch of guys trying to make a crack in the world to having people trying to smash down doors to see your band. That’s the most amazing time, and it only happens once.

Steven, do you still get women thanking you for providing the soundtrack to their formative sexual experiences?

ST: Yeah, I get that. I get that from guys too. I heard it from Nancy Pelosi [the former speaker of the US House Of Representatives, and currently the Democrats’ leader in the House] that a lot of the songs that Aerosmith wrote and I sang she got laid to for the first time. I love being a part of people’s lives like that. I love that Joe and I sat around once and said: “Fuck, we gotta write something,” and we got going and wrote Moving Out. I’m still honoured to be able to be a musician, that’s just a troubadour going from town to town, writing stories about the last town I was in – where the motherfucking dude looked like a lady – and those songs still living. I love it. Although I’m not very partial to that song. I like Love In An Elevator a little more, or What It Takes.

So what comes next?

JP: I’ve got a batch of songs I’m getting ready to release. I’m just anxious to be able to play them live. We’re in the middle of finishing them off right now, and they’re really different to anything I’ve done before. So if Aerosmith wasn’t around I would be definitely putting the Joe Perry Project back together so I could go out and tour. I also have the Hollywood Vampires coming up on the horizon and that’s going to take a bit of work, too. I’m hoping that all falls together, between Alice [Cooper]’s schedule and Johnny [Depp]’s and mine. Since we postponed the American tour with Aerosmith, I’m hoping we get time to do some of the stuff.

Does that mean there won’t be a new Aerosmith album?

JP: Not at all. Steven and I have talked about it. It’s just a matter of when. He’s got his solo thing that he does. And there’s times when he’s doing other stuff. But, hey, ultimately I would really like to get in the studio with him and the other guys and do some stuff in the next six months. It doesn’t have to be a whole fucking album. We’ve got enough songs that we could play until 2025 and never do the same set twice. But I still think there’s some riffs in there that if the band got together, we could really sink our teeth into.

ST: I don’t know how that’s going to go. The band want to do a farewell tour in the States, but if we did that we would be out for a year. I don’t know when we’d have time to do another Aerosmith album. I just spoke to Joe about that the other day. I told him I’d love to do a Toxic Twins album.

Steven, it’s twenty years since you sang that Falling In Love (Is Hard On The Knees). Now you’re sixty-nine, is it even harder on them?

ST: It is. Because the more you learn, the more you’re afraid to give up. In the beginning you’ll fall for anything, if you don’t learn what to stand up to. Love can take you down. But it’s a strange world now. I’m not sure if I’m falling in love with more things, or just relying on the old things I love the most and trying to get back to them.

Aerosmith play Download Festival on June 11.

The story behind the song: I Don't Want To Miss A Thing by Aerosmith